Herman And The Serpent

How a retired diplomat in Wellington brought a notorious murderer to justice.

By Tobias Buck

Saturday morning on 19 September 2003 was a cool spring day in Wellington. It was the first day of Herman Knippenberg’s retirement and he was looking forward to a breakfast of pancakes. That was when the phone rang. It was a call from a friend in Auckland, informing him that the serial killer Charles Sobhraj had just been arrested in Nepal.

“Nunc aut nunquam,” Herman says of that day. “It was a now-or-never situation.”

Herman often says things like this. In his early 70s, tall and personable, his manner is just on the friendly side of brusque. Herman loves a good turn of phrase. He has an unending stock of them in English, Latin and German.

I first met Herman about a decade ago, when I worked at Unity Books Wellington. Literary conversations are common there, so I wasn’t surprised to hear a Dutch-accented voice over my shoulder one day, asking how many novels by Patrick McGrath we had. He was also a fan of Heinrich Böll. Soon we were swapping titles and looking through the shelves.

Herman had a list of books he was after and pulled out a notebook with publishers’ names and release dates. If you’re familiar with working retail, you’ll know this isn’t always a good sign. But the topics Herman was tracking were always interesting. He’d pop in and we’d chat about Graham Greene or Carlos the Jackal, or literary crime novels sprinkled with espionage.

Once, we were informed by a publisher that a book Herman had ordered was going to arrive a few days late, and I got my first clue that Herman can be uncommonly determined. A man who does not accept no easily. “It’s not about what they’re telling you,” Herman said, convinced that there must be some way to get the book promptly. “It’s about what you think!”

We became friends. I would go for afternoon tea at his home. There’s a white picket-fence outside, comfy chairs by the window and always a good variety of biscuits. I learned that Herman had been a career diplomat for the Dutch government. He’d lived in Athens, Luxembourg, Vienna, New York, Jakarta and Thailand. In 1987, he met his second wife Vanessa — a Kiwi — in Vienna. Also a career diplomat, and just as animated as Herman, she was posted to the New Zealand Embassy at the time.

There was something about Herman that wasn’t everyday. Sometimes he’d say things like, “As you may know, I was in Bangkok at that time.” Or, “Because of my involvement with the case.” Herman himself never dropped me in the deep end of his life story. Which I appreciate. It was a colleague at the bookstore who mentioned Herman had his own section of a Wikipedia page. It was only slowly, one clue leading to another, that I learned that Herman once helped to catch a serial killer.

“The good news is that your intelligence level is high,” Herman was told in a psychological evaluation. “The bad news may be that you experience problems with authority from people you can’t respect.”

For a time in the 1970s, Charles Sobhraj was one of the most wanted men in Asia. Police in multiple countries had tried and failed to apprehend this sophisticated conman for his lurid despatchings of young travellers on the Hippie Trail. In the media, he was variously known as The Bikini Killer, The Splitter and The Serpent, nicknames inspired by his grisly methods and slippery evasions. By the time of his capture, Sobhraj had variously poisoned, drowned, strangled, stabbed and burnt 12 people. At least 12 people.

There have been two films, four documentaries, and several books about Sobhraj over the years — a perennially charming monster, he almost seems custom-made for crime thrillers. Netflix is now screening The Serpent, an eight-episode BBC co-production that, for the first time, highlights Herman’s critical role in apprehending Sobhraj.

Stories about serial killers are a dime-a-dozen. Stories about the real people who catch them are rarer. When I asked Herman to tell me about his role in the case, he was characteristically prepared.

Herman can cite every article on Sobhraj in detail, with the fervour of a young lawyer or investigative journalist. “We will make a piece that can withstand scrutiny,” he declares. He frequently backtracks and qualifies his statements for factual precision.

Over a series of phone calls, he becomes increasingly invested in this article — not just in its accuracy, but in how his tale is told. He has a suggestion for a title, and an idea for how the story should start. He insists we recognise the Canadian Ambassador in Thailand, a figure almost no book or article has mentioned. (“Bill Bauer. Don’t forget how important he was. He was formidable. A pillar of the west.”)

At the start of our first conversation, I can hear papers being rearranged in the background.

“I’m ready for it. Shoot. I have everything on hand. Personally, I think we should start with the day Sobhraj came back into my life. The day he was arrested in Kathmandu. That’s when the New Zealand Police became involved. I remember it clearly.”

I can hear him settling into the story.

“Yes. It was a Saturday morning on the 19th of September 2003. A cool spring day in Wellington. It was the first day of my retirement and I was looking forward to a breakfast of pancakes. That’s when the phone rang.”

Herman Knippenberg. Photo: Victoria Birkinshaw.

Herman Knippenberg was born in Breukhuizen, a small town in the Netherlands close to the German border. His father was a doctor and a member of the Dutch Resistance. Tiger tanks would roll through town and SS officers would knock on their door to ask his father’s whereabouts. In October 1944, when Herman was six months old, his family home was destroyed, likely by an Allied bomb dropped in the Battle of Overloon. His mother put him in a pram and walked 50 kilometres to his grandparents’ house. That’s where Herman was raised.

Herman consistently graduated top of his class, but from his very earliest years, he liked to do things in his own way. “I was always a difficult child,” he says. “My mother would give an instruction and I would do the opposite. I would not take issue — I would just do it very differently. Between three and five I would correct anyone making a mistake reading my favourite books to me. ‘No, that’s not what the author said,’ I would say. I would let them know!”

At 19, after hitchhiking through Syria and Turkey for three months and spending two months in Egypt, Herman applied to the Diplomatic Service. “In my psychological testing they said, ‘The good news is that your intelligence level is high’,” he recalls. “‘The bad news may be that you experience problems with authority from people you can’t respect.’”

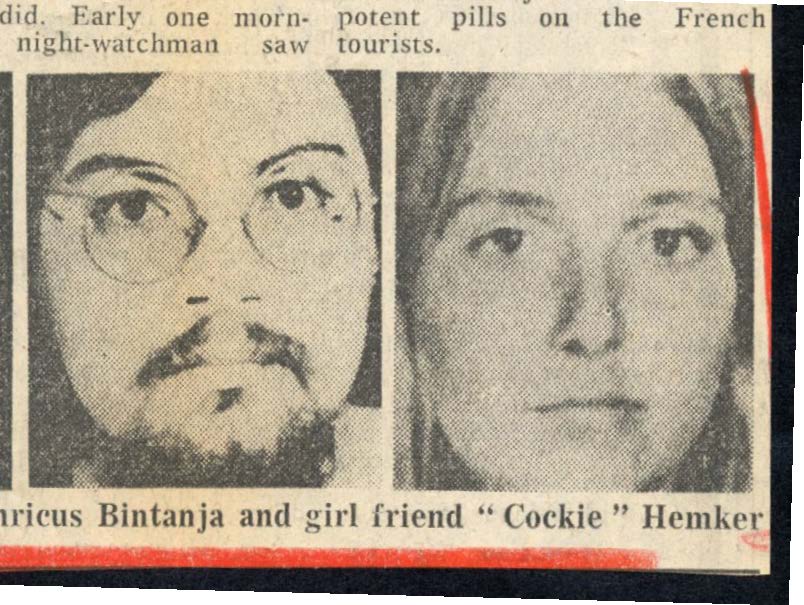

In 1976, aged 32 and still early in his career, Herman was working as a junior diplomatic officer at the Dutch Embassy in Bangkok when he was asked to make inquiries about two Dutch backpackers who’d been traveling in Thailand: Henk Bintanja and his girlfriend Cornelia Hemker. Their families were worried: there had been no letters home for six weeks — not for Christmas or the birthday of Cornelia’s mother and sister. Based on his own experience as a backpacker, Herman’s intuition told him something was up. He felt propelled by kinship as well as duty.

Sunday Times report on Henk Bintanja and Cornelia Hemker. Photo: Supplied.

The couple’s last contact mentioned a French man in Hong Kong who’d sold them a gemstone at a low price and invited them to join him in Thailand. Herman learned that Henk and Cornelia had never reached the hotel that they had listed on their arrival card. He also knew that a few months earlier, the bodies of two tourists, supposedly Australian, had been found in Bangkok. There had been articles in the local press but no one, including the Thai police, had any leads.

“As they say in the Netherlands, they had heard the ringing of the bell but did not yet know where the clapper hangs.”

A detail caught Herman’s attention: one of the dead tourists had been wearing a t-shirt made in Holland. He contacted the Australian Embassy and was told that the two Australians who were originally suspected of being the victims were still alive. So Herman obtained the missing Dutch tourists’ dental records and used them to confirm that they belonged to the burnt remains sitting in a Bangkok morgue. Herman himself went to identify the bodies. “I will never forget it,” he says.

In theory, this is where Herman’s role as a diplomatic officer should have ended as the Thai police took over. But Herman doubted the police were sufficiently motivated and so he stayed on the case.

Once he started to look into the matter, he heard rumours of other suspicious backpacker killings in Thailand, as if there was a bogeyman stalking the Hippie Trail. A young woman named Teresa Knowlton had been drugged and abducted and then dressed in a bikini and left on a beach. “Knowlton was off to become a nun you know!” Herman says. When he first told me this, I wasn’t sure whether to believe him. The body of another young traveller, Vitali Hakim, had been found burnt on the side of the road.

Not long after the Dutch tourists were identified, a man and woman had used the victims’ passports to fly to Nepal. The couple returned to Thailand five days later on the passports of two more backpackers, American Connie Bronzich and her Canadian friend Laurent Carriere. It would emerge that Bronzich and Carriere had also been murdered: stabbed multiple times and charred beyond recognition.

Herman’s investigations were pulling at every aspect of his own life. His first wife Angela was supportive and helped with the research, but Herman was increasingly on edge. His superiors at the embassy were growing frustrated that he was apparently more focused on chasing a murderer than carrying out his administrative duties.

Via a good friend at the Belgian Embassy, Herman heard of a suspicious character named Alan Gaultier. He also got word of an apartment where the Dutch couple might have stayed. It had a reputation as a frequent site for parties of travellers, hosted by a mysterious French man who was also named Alan Gaultier. Neighbours in the building had reported screams.

As it turned out, the host of the parties at the apartment was a different Alan Gaultier. But, improbably, the link had led Herman to the crime scene.

“I couldn’t believe the coincidence. It was a deus ex machina. Like something in a cheap airplane novel!”

Herman was given permission by Thai police to enter the empty apartment. He assembled an action team — himself, his Belgian friend, an American Embassy contact and one of the neighbours. Inside, they found 12 Western passports and large plastic tubs of sedatives and syringes. Herman recalls seeing scratch marks on a bedpost that he’d later realise were made by victims handcuffed to the bed.

Herman took his findings to Thai police and pressured them to make an arrest. But when confronted, “Alan Gaultier” produced a forged US passport in the name of David Alan Gore. This deception got him out of Thailand.

His name, of course, was not Alan Gaultier or David Alan Gore but Charles Sobhraj. By this point, he knew the authorities were on his trail — and became even more extravagantly violent. He next popped up in India and travelled on the passport of an Israeli tourist who had gone missing there. He also fatally poisoned a French man named Jean-Luc Solomon. The Indian police were alerted. Then, in July 1976, with two new accomplices, Sobhraj insinuated himself as a local guide for a French tour group of 22 students in New Delhi. He offered them anti-dysentery medication and intentionally overdid the dosage. As the victims stumbled around the lobby of the Vikram Hotel, he was held in the bar by three of the party until the Indian police arrived and arrested him.

Herman had just returned from a fishing trip when he received a call from the Canadian Ambassador, Bill Bauer. “The Indian police have also been fishing,” Bauer informed him. “And you won’t believe what they’ve caught!”

The French tour group survived, but Sobhraj was tried for the murder of Jean-Luc Solomon. This was how his full identity finally came to light.

To say Sobhraj enjoyed his notoriety is an understatement. He revelled in it in a way that makes your skin crawl.

Of Indian-Vietnamese descent, Charles Sobhraj was born in Saigon. He was partly raised by a French Army stepfather and ferried between Indochina and France as a child. Imprisoned for petty crimes as a teen, he bribed guards to make his cell more comfortable. After his release, he headed for Southeast Asia with an entourage that included his younger brother André and various girlfriends and accomplices. They established a pattern of robbing jewellery stores, being caught, feigning illness and escaping jail.

Sobhraj cut a debonair figure in Bangkok, equally comfortable in society and the backstreets. He spoke five languages. He sported tinted sunglasses and berets, turtlenecks and sports jackets. Passports were his currency, identities his objective. He inveigled himself into travellers’ lives with a rock-star swagger. He was capable of organising anything; gems, drugs, a bed to sleep in. His victims were usually those who attempted to resist his lure and keep moving.

There is something both righteous and cavalier about Sobhraj’s killings. He’d openly joke with people about “dirty”, easy-going Western travellers who treated his home as their “experience”. He wouldn’t drink or smoke himself, showboating his self-discipline over their indolence.

In 1976, Sobhraj was sentenced to 12 years at Tihar Prison in New Delhi. He immediately ingratiated himself with the guards and prisoners. A TV was installed and he was served gourmet food.

Ten years into his term, Sobhraj escaped and let himself be re-arrested in Goa, thereby adding another 10 years to his imprisonment. It was an ingenious strategy to dodge a likely death sentence in Thailand: after 20 years, the statute of limitations on the murder of the Dutch tourists would expire. By 1997, Sobhraj was free and living in the suburbs of Paris.

To say Sobhraj enjoyed his notoriety is an understatement. He revelled in it in a way that can make your skin crawl. He gave TV interviews and sought to negotiate film rights.

By this point, Herman was living in New Zealand. He and Vanessa had settled there in 1999. Over the phone, I can hear how galled he still is by the idea of Sobhraj giving interviews for cash.

“It was a hullabaloo. A circus. Americans paying thousands of dollars to lunch with a killer. It was a terrible thing to stomach.”

And then, in 2003, after six years in France, Sobhraj made a remarkable miscalculation: he returned to Nepal. Within hours of leaving the airport he was spotted at a casino by a local journalist. After following Sobhraj for a fortnight, the journalist published a report with photographs in The Himalyan Times. Sobhraj was immediately arrested and charged for the 1975 murder of Connie Bronzich.

There was just one problem, however. The evidence to convict him was in Wellington, sitting among an assortment of old furniture in Herman’s garage.

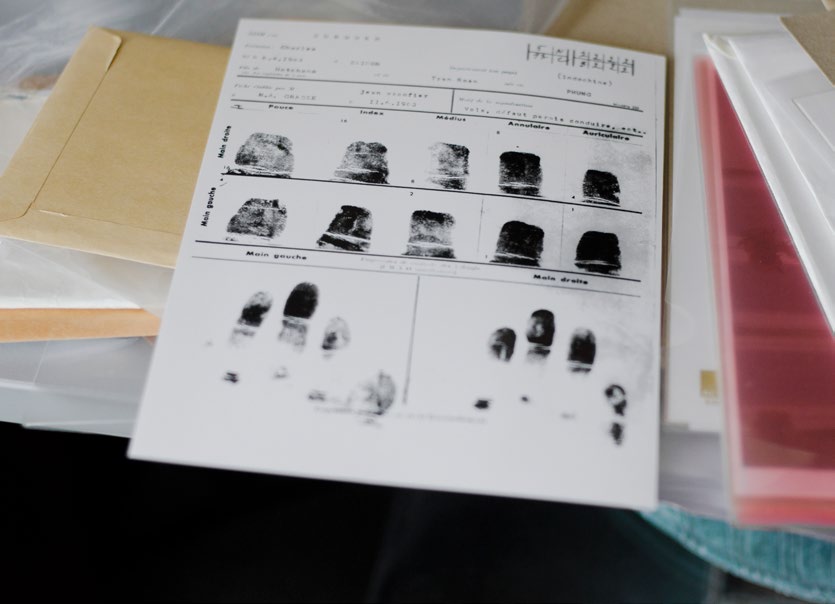

Boxes of evidence that Knippenberg kept for years in his Wellington home. Photo: Victoria Birkinshaw.

For 30 years after the murder of the Dutch tourists, travelling the world on his diplomatic passport, Herman had taken five cardboard boxes of evidence with him. Witness statements, embarkation cards, hotel bills, flight manifests. He’d given copies to the relevant police authorities, but, fearing the case would continue to be brushed aside, kept the originals for himself.

After he got the call alerting him to Sobhraj’s arrest in 2003, Herman dug the boxes out and rang the New Zealand police. Two Wellington detectives verified the documents so the evidence could be submitted to Interpol Nepal and the Kathmandu authorities.

Herman’s evidence was key to the prosecution. It refuted Sobhraj’s claim that he wasn’t in Nepal at the time of Bronzich’s murder. In 2004, Sobhraj was sentenced to 14 years in solitary confinement in Nepal’s Central Prison.

Once Herman gets going on the subject of Sobhraj,he can be hard to interrupt. In 1986, he even wrote a Harvard PhD dissertation on leadership that uses Sobhraj as a case study. “He is that dark Nietzschean ideal — an Übermensch living, in extremis, on the slopes of Vesuvius,” Herman tells me. “A ‘charismatic leader’ constantly having to prove himself, believing himself innately superior to others. I have always had a problem with such forms of false authority. Wherever they appear. I refuse to be enamoured by him. I won’t let him pervade me in that way.”

Still, he maintains that Sobhraj is not an obsession for him. “Though I fear it will not be over until he or I is in a better world. He really comes in and out of my life like malaria,” he says.

This rather typifies Herman. He’s both the world’s foremost expert on the case and almost strategically dismissive of its hold over him. “To help safeguard your own people while you are sitting comfortably at a desk,” he says. “Was that not our responsibility?”

Fingerprints from evidence collected by Herman. Photo: Victoria Birkinshaw.

One rainy day in September 2013, Herman received a letter in the wooden mailbox at his gate. “A very Wellington letter,” he says, laughing. “Wet enough not to fly off in the wind, but still quite readable.”

“‘Dear Mr Knippenberg,’ it began. ‘I apologise writing to you uninvited.’”

The letter was from Mammoth Productions, a writer-led company in the UK. It explained that one of their team had been travelling through Nepal in the 1970s and remembered the long and frightening shadow cast by Charles Sobhraj in those years.

“It was that heady, free-wheeling era when people travelled without mobile phones or the internet,” recalls director Tom Shankland, who travelled to Nepal in the 1980s. “It was so unsettling to be in such an astonishingly beautiful place and picture such bleak and brutal murders.”

The company was interested in making a show about the killings — but only if Herman would be part of the project: “Without your meaningful involvement we are only adding to the conjecture and the self-serving mystique and conjecture that lies at the heart of the fascination with Sobhraj.”

“It really was a very well-written letter,” Herman notes.

A call was arranged between Herman and the company. Herman told them about some of his own cinematic interests — the films of Ingmar Bergman, television adaptations of the Southeast Asian stories of Somerset Maugham.

“They said ‘That stuff is not available commercially’,” Herman says. “I told them ‘Oh yes, I know. But I have managed to secure some’.”

If Herman would work on the show, the filmmakers said, they might be able to provide him some more episodes of the Maugham series. Herman agreed to come on board.

Main photography on The Serpent took one year, with filming over seven months and setbacks due to Covid-19 and the Thai rainy season. Herman has been involved as an advisor since 2014. His near photographic memory has come in handy — he is able to recall minute details such as where people were sitting in a room. Based on Herman’s love of Carlos, a mini-series about Carlos the Jackal, its production designer, Francois Renaud Labarthe, was contracted to work on The Serpent.

The show has been a breakout hit in the UK, capturing 1970s Bangkok with a mix of found footage and stylish production. At the time of writing, it’s the most-watched show on BBC iPlayer, with 31 million views. Tahar Rahim plays a smooth, cold version of Sobhraj, while Jenna Coleman performs the complex character of Marie-Andrée LeClerc, Sobhraj’s love interest. Herman was especially excited by the portrayal of Lieutenant Colonel Sompol Suthimai of Interpol in Thailand. “I was a frustrated academic at best, but Suthimai was a true investigator. And we always met in such nice restaurants.”

For Herman, the experience of seeing himself on screen has been “a mix of the nostalgic and the surreal”. Billie Howle, who plays the young Herman, has his forthright manner and zeal down pat. Herman thinks it’s brilliant.

Still, there is an innate problem to telling Sobhraj’s story, one shared by police, journalists, screenwriters and Herman himself over the years: the real tale of The Serpent is almost too dramatic. The details beggar belief.

Knowlton was indeed heading off to be a Buddhist nun when she was killed: I checked, and of course, Herman was correct. When Sobhraj escaped jail in Tihar, he did so by drugging a cake and inviting the guards to his own birthday party. He walked through the open jail yard and out the front door, waving at the watchtower as he went.

Billy Howle as Herman in the BBC series The Serpent. Photo: BBC © MAMMOTH SCREEN.

Jenna Coleman plays Sobhraj’s love interest Marie-Andrée LeClerc. Photo: BBC © MAMMOTH SCREEN.

Herman believes Sobhraj has more victims whose murders were never proven. He mentions a Pakistani taxi driver who was drugged while Sobhraj travelled from Tehran to Kabul. Also a bearded American shot in Thailand. A middle-aged Frenchman drowned in a bathtub in the Chiang Inn Hotel. Of Sobhraj’s 12 known murders, eight took place just in the six months before he was jailed. Before he was stopped, he was speeding up. It’s all so utterly fantastic-sounding that the Netflix show had to tone down some of the details, like the bizarre coincidence of the two Alan Gaultiers. “There’s only so much viewers can accept!” Herman says.

True to form, Sobhraj has sought to profit from the Netflix show, threatening to sue over the rights to his life story. He’s continued to give interviews — denying any involvement in the murders — and has appealed to French President Emmanuel Macron to be released from prison in Nepal. But he almost never mentions the man who put him there.

When I first interviewed Herman, I thought we might be talking about how an indiscriminate evil had derailed a life. I’d learn, from someone I liked, about his struggle to outlast a tragedy he’d stumbled into inadvertently. But in Herman, Sobhraj met his natural counterweight.

In one corner is Sobhraj, this intelligent, evasive killer-without-limit, with a worldview in which all crimes are escapable, all authority corruptible, thriving on chaos. In the other corner is the quietly implacable Herman, also a force of nature — a “chaotic good”, you might say — refusing to let go of the case and challenging the status quo.

“I was outraged. Truly. I was not afraid, because there was no time. Not for explanations. The only relevant thing was that he must be stopped.”

I ask what he most hopes The Serpent will get across and his answer is immediate.

“A warning to youngsters. We should all go see exotic places. We must. We should. But we must be careful. You could tread on a serpent. Not just a King Cobra but one with two legs. It is so easy to be trapped. A favour accepted. A pill in your drink.”

“Also,” he adds, “I wanted them to show the necessity of fighting the inertia of bureaucracy. Of not accepting the obstruction of your superiors. If your conscience is pricked strongly enough to act, then you must do something. You simply must.”

As Tom Shankland, The Serpent’s director puts it, Herman was also “pushing against the somewhat patriarchal, colonial values” of his time. Just like those young travellers. In Herman’s case, the obstacles were inside “the diplomatic service and expat community”. Herman simply couldn’t accept that “the murder of a young Dutch couple could slip completely beneath the radar”.

I’ve been interviewing Herman on the phone for a few weeks now. I make sure to call promptly at 9am and he usually picks up on the second ring. The batteries on my headphones are going flat again as I fill pages with notes.

It’s dawning on me just how many times Herman has had to tell this story and how much resistance he’s encountered along the way. It’s why he can’t hold back his urge to be specific, to take control of the story: an unlikely hero, he has all too often had to fight to convince people.

At one point, it occurs to me to ask Herman if he watches crime shows on TV.

“I don’t even like serial killers!” he says. “I’m not good at following all those flashbacks. It really does get too complicated. Vanessa is better at that sort of thing than me. I’ve only followed one crime story in my life. And I can tell you this with utmost certainty. That one was entirely sufficient.”

Tobias Buck is a writer from Hawke’s Bay who is based in the Netherlands.

This story appeared in the April 2021 issue of North & South.