Lost In The Clouds

As a new generation succumbs to nicotine addiction, New Zealand’s approach to vaping has been bafflingly lax.

Story by Don Rowe

Illustration by Paul Blow

Nestled between the wealthy suburb of Kohimarama and the Hauraki Gulf, Glendowie College in east Auckland is one of the city’s most respected public high schools, with a clean-cut image to match. Until very recently, according to former principal, Richard Dykes, discipline issues were pretty minimal — just an occasional cigarette smoker or truant. But then, after the summer holidays in 2019, something changed.

“Suddenly, oh my goodness, every day we were picking up multiple students vaping,” says Dykes. “It felt like a tsunami had crashed.”

Alerted by the tell-tale scent of candy-flavoured juices, or the billowing yet ethereal clouds of vapour, teachers were catching students vaping everywhere — in the grounds, in the toilets, even during lessons. “One of the games was trying to see who could vape in class,” says Dykes. Students would hide their device in their sleeve, take a hit and then breath the vapour back into their jumpers to mask the smell. Around this time, Dykes started hearing similar complaints from colleagues at “multiple schools” — particularly high-decile ones where students typically had more disposable income. By the end of the 2019 school year, Dykes had between 70 and 100 vape devices in his office drawer. He wasn’t the only high school principal to start using the word “epidemic”.

Vapes, once more commonly known as e-cigarettes, are non-combustible nicotine delivery systems that heat a flavoured “juice” or e-liquid to create clouds of nicotine-infused vapour. You’ve likely seen — or smelt — one. They’re promoted by the vaping industry and the government alike as a healthier alternative to cigarettes. But that doesn’t mean they are actually healthy. A growing number of academics, researchers and medical professionals believe vape companies have long abandoned the pretense that their product is a cigarette alternative and instead are creating a new generation of first-time vapers (and nicotine addicts) — particularly among younger New Zealanders.

In 2019, a study by Action for Smokefree 2025 showed that regular vaping among Year 10 students increased from 3.5 per cent to 12 per cent in four years. During this period, the number of Year 10 students who smoked regularly was essentially unchanged — meaning the rise in student vaping had negligible effect on reducing smoking rates. Another survey of 7700 New Zealand adolescents between 13 and 18 years found that two-thirds of kids had tried vaping. Half of those who were regular vapers had never smoked before.

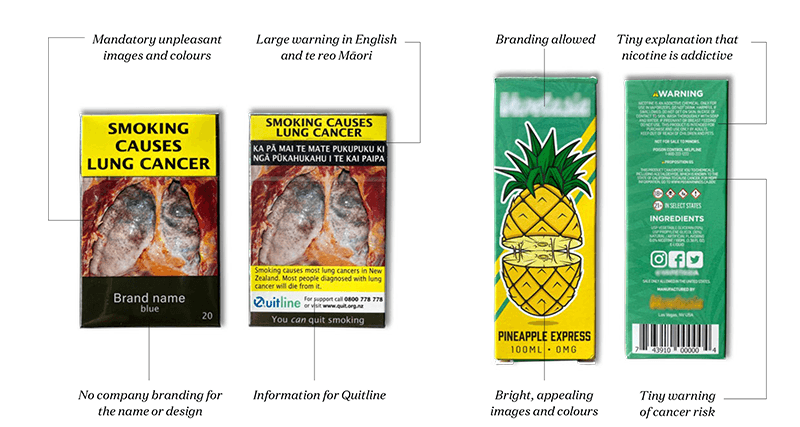

New Zealand has some of the strictest tobacco control laws in the world. By contrast, our approach to vaping has been inexplicably lax, a regulatory wild west. In the United States, vaping laws have been heavily fortified at a federal level for some time, with strict regulations around advertising, product quality and availability. In New Zealand, until just November last year, products delivering nicotine levels far in excess of a cigarette were available to people of any age, without restriction.

Even now, vaping exists in an entirely different regulatory universe than tobacco. Where it is an offence to smoke in a vehicle carrying minors, it remains legal to vape. Where cigarettes are stowed away in plain packaging behind the counter, vape retailers can display a vibrant range of innumerable flavoured juices, cool, minimalist vaping devices and even branded apparel. A new law that came into effect last November patches some of these holes, but still leaves major gaps remaining. Advocates have lobbied to bring the law in line with comparable countries abroad — but meanwhile the vaping industry has been doing plenty of lobbying of its own.

For Dr Sommer Kapitan, a behavioural scientist at Auckland University of Technology (AUT), much of the damage has already been done. Industry moves much faster than regulation, she says, and by now a generation of highly impressionable young customers have been exposed to the cutting-edge marketing tactics of both Big Tobacco and the local vape market.

“If you get customer loyalty from someone where it’s just embedded in their subconsciousness and social milieu, that person is likely to buy from you, and to keep buying,” she says. “If you can make your product exciting, attractive and interesting to people at that age, well, that is hard to undo. If you can land a young person, that is your golden goose.”

The E-Cigarette was invented in the early 2000s by Chinese pharmacist and three-pack-a-day smoker Hon Lik following the death of his father to lung cancer. These first-generation devices, popularised by pharmaceutical firm Ruyan, looked like cigarettes — yellow filter, white stick, even a fake red coal on the tip — and were geared exclusively towards the reticent smoker.

By 2014, when the second generation of vape pens appeared, they included a “clearomizer” that combined the device’s heating function with an atomizer which produces vapour, generally in the form of a cottonwrapped electric coil soaked in flavoured juice. Since the latter years of the last decade, the third generation of vapes can be seen clutched by businessmen on any CBD street in Auckland or Wellington: large brick-like contraptions with a “tank” of juice and a wide mouthpiece. And then came the fourth generation.

In June 2019 — about the same time that Dykes first noticed the vaping “tsunami” at Glendowie — Dr Kapitan returned to work at AUT after a sabbatical abroad. “Suddenly there were groups of students vaping outside my classroom,” she says. “They were not there six months ago — something happened. And the thing that happened was clearly the availability, familiarity, accessibility and aesthetic appeal of these products.”

Fourth-generation vapes are sleek, futuristic devices that fit easily in the palm of your hand. Where the early, clunkier models were designed to create the biggest hit of vapour, fourth-generation vapes are smooth and surreptitious, packaged in stylish, Silicon Valley boxes — the iPhone to the third-generation car-phones. Vapes had become more than a product — they’re a lifestyle.

The evolution of the e-cigarette.

The most famous (and successful) of the fourth-generation devices is the Silicon Valley start-up Juul, a monochromatic pen that looks like it has rolled straight off the Apple production line. That aesthetic is no coincidence: The Juul was created by two Stanford design graduates. The company’s stated mission is to help “one billion adult smokers” and dominates more than three-quarters of the US e-cigarette market. In New Zealand, a Juul “starter kit” retails for around $100.

In 2018, cigarette giant Altria, the parent company of Philip Morris USA, purchased 35 per cent of Juul for US$12.8 billion, rocketing the company’s value to $US38 billion and making founders Adam Bowen and James Monsees the first e-cigarette billionaires. But the acquisition also raised significant questions about their mission statement. That same year, research revealed that 3.6 million American high school and middle school students were using e-cigarettes. FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb declared a vaping “epidemic” in the United States, saying that e-cigarettes had become an “almost ubiquitous — and dangerous — trend among teens.”

Stepping into a specialist vape store today is an aesthetically flattering experience: all burnished chrome, soft lighting, and glass cabinets. From Big Tobacco-backed producers to local manufacturers, devices and e-liquids are promoted with soft pastels and tones of summer, paired alongside scenes of artists and DJs. Actor and George FM DJ Tammy Davis has served as an ambassador, posting ads for the Vype pen on his personal Instagram, as has Marc Moore, the creative director of fashion brand Stolen Girlfriends Club. (Outside the world of celebrity, there’s still something for everyone — one New Zealand brand, “Get Hooked”, is geared towards the vaping fisherman.)

In 2018, at the Rhythm & Alps festival outside Wanaka, Vype, the flagship vapour brand at that time for British American Tobacco New Zealand (BATNZ), ran its own selfie booth. Festival-goers could win tickets to an upcoming show by dance act Fatboy Slim by posting a photo with Vype branding and the requisite hashtags. Scrolling through Instagram, the hashtag leads to shots of predominately young partiers, smiling, laughing and — in at least one case — getting their breasts out, Duct-taped nipple shields and all. The ingenious thing about this approach is that vape companies don’t need to pay creative agencies to find models, stage expensive photo shoots and plaster the images on billboards. Their own customers do their marketing for free — and their personal social networks reach further and deeper than any tobacco company could ever penetrate.

Vype also sponsored the 2019/2020 edition of Rhythm & Vines, the country’s largest New Year’s Eve festival. The company set up a branded on-site charging lounge and vape station. Rhythm and Vines is an R18 event, and Vype was acting within the law, but Kapitan says it is a long shot from being the target demographic for a product that is ostensibly meant to help smokers. Products marketed to people in their early 20s also look particularly fashionable to people a little bit younger, she adds. “It was clearly the playbook of everything we saw during the era of Big Tobacco. I had never seen that here before.”

Many vape juice varieties sound more like a healthy smoothie than a potent nicotine delivery system: Crisp Mint, Strawberry Burst, Green Apple, Peaches and Cream, Taro Milk, Watermelon Ice.

Event sponsorships will no longer be allowed under the new regulations. However, vape companies have another tool to build loyalty in a way cigarette companies could only have dreamed of. Every vape needs juice, and according to the Asthma Foundation, there are more than 7000 on the market. The flavours range from cola to milk custard to boysenberry ice and beyond, but the active ingredients are a lot less appetising: a mix of vegetable glycerine, propylene glycol and nicotine. Finding the right flavour — and nicotine level — is as much a part of the identity project for many as picking up a vape at all.

Many vape juice varieties sound more like a healthy smoothie than a potent nicotine delivery system: Crisp Mint, Strawberry Burst, Green Apple, Peaches and Cream, Taro Milk, Watermelon Ice. “It’s clear to me that they are trying to appeal to young people,” says Kapitan. “‘Fresh farmed peach soda’ is not going to appeal to a pack-a-day truck driver.”

Nor, perhaps, will saccharine soda flavours and confectionary inspired juices like Boysenberry Lemonade or Candyfloss.

Vape juices come in a range of strengths, generally measured in milligrams per millilitre. At the lower end, 4mg/ml delivers far less nicotine per inhalation than a cigarette. But at the upper level, around 50mg/ml, each hit on a vape delivers a powerful rush of nicotine, made more bioavailable by modern nicotine salts. While a vape user is exposed to far fewer chemical additives than a smoker, it’s easy to develop a powerful addiction simply by puffing away with any amount of regularity. According to the Vaping Trade Association of New Zealand, flavoured options make up 90 per cent of juice sales, in a market with a value of around $200 million a year.

I loaded up the website of Vapo, a Kiwi brand whose co-owner Jonathan Devery serves as spokesperson for the Vaping Trade Association, and who has advised the government on potential vaping regulations. Before I had confirmed my age, I was redirected to a quiz which asked me to choose my favourite cocktail, my perfect date, my favourite season and my ideal holiday. It was essentially the type of personality quiz you would find on a meme-regurgitating website like Buzzfeed. After inputting my choices, I was offered a 20 per cent discount on Mango Crush.

In New Zealand, new regulations this year will see general retailers like petrol stations and dairies limited to tobacco, mint and menthol flavours, with the rest sequestered away in specialty vape stores. These stores have experienced an explosion in popularity all over the country, with new players like Vapo competing with former bong retailers like Shosha to secure prime main-street real estate. Unlike in markets such as the USA, there are no restrictions on the packaging of vape juice. The end result is hyper-colourful labelling adorned with cartoon fruit, billowing clouds and company branding — a stark contrast to the plain packaged cigarettes hidden behind the counter.

Advocates for stricter control believe lower limits on nicotine content in vape juice are essential, as well as stronger government messaging to emphasise the importance of transitioning away from vaping as an end goal. A distinction must be made, they say, as to whether vapes are commercial products or a medical tool. And because vaping is much cheaper than smoking over the long term, they also want much greater scrutiny on who is accessing vaping products. A 30-millilitre bottle of high quality juice would last even the heaviest vaper well over a week for $35 — a little more than the cost of a single pack of cigarettes.

The Vape Trading Association has lobbied successive governments to regulate the industry, saying it is impossible to operate in an environment of uncertainty. In large part, the industry self-regulated to prohibit the sale of products to under-18 year olds before a government ban. But it is pushing back hard against restrictions on where flavoured juices can be sold. It argues that making flavoured vaping less accessible will disincentivise smokers from making the switch from combustible cigarettes. For similar reasons, it wants the freedom to set nicotine levels in vape juices, and is lobbying against a ban on advertising vape products.

For Dr Kapitan, the far greater risk of allowing advertising is that non-smokers will become hooked on vaping. “If you’re trawling for fish you might catch turtles, but in this case you’re catching way more turtles than expected. And so the question is, is it worth it to lose the fish? Because right now we’re getting a lot of turtles.”

But how many, exactly? Letitia Harding, chief executive of the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation, began following vaping data in 2017. Concerned at the dramatic increases she was noticing abroad, Harding warned the Ministry of Health that New Zealand could see an upswing in respiratory health problems.

In 2020, a Ministry of Health-funded study of 14 and 15 year-old students found that only a third had tried vaping — leading to claims that talk of a teen vaping “epidemic” was overblown. However, Dykes, the former Glendowie College principal, notes that the study focused on an age group he believes is less likely to vape or smoke. It is senior students, he says, that tend to engage in either habit.

Among my own group of 20-something friends, vaping has become ubiquitous to the point that it’s more significant if someone doesn’t vape than if they do. Whether at home, at work, out on the town or at a music festival, a vape is always within reach, and everyone has their consumer preferences. Very few of my social group were smokers before they started vaping.

For Angie, a 28 year old from Wellington, vaping has become a daily activity for her and “almost everyone I know”. When her new boyfriend started vaping, she borrowed his device and then bought her own. “I chose the same vape that my friends had,” she says. “I definitely don’t vibe with the giant tank ones. I like the sleekness of it, it’s just more, I don’t know, classy?”

Before long, Angie found herself taking regular vape breaks at her office job. As we speak by phone on her lunch break, she notes five people within view staring into their phones and vaping away, clouds of fruity vapour drifting out across the footpath.

As a professional working in the marketing field, Angie is very aware of the tricks advertisers use to promote their products. But despite being particularly savvy about these techniques, she admits that she’s still susceptible to them.

“The marketing is really powerful. I’d never, ever liked cigarettes and I don’t know why vaping is any different, but it has this ‘cool kid’ thing attached to it,” she says. “Because we’ve been fed this story that it’s healthier than cigarettes, we’re all doing it without thinking about health implications. It’s kind of ingrained in me now that it’s all good, even though subconsciously I probably know that it’s not.”

Cigarette and vape juice packaging: a comparison.

In 2017, the Government established an expert advisory panel on e-cigarette product safety. The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation was troubled to find that the group had no medical experts in respiratory health on it — but did include representatives from the vaping industry, including vape suppliers NZVapor and Cosmic. According to Harding, the foundation tried to get respiratory physicians added to the panel, but were unsuccessful.

Doctors and researchers unanimously agree that vaping is a healthier alternative to smoking cigarettes. However, there is little available data about the effects of long-term use. The common claim that vaping was “95 per cent safer” than cigarettes has been widely debunked and removed from the government’s own Vaping Facts website. And a lack of quality-control regulations in New Zealand means that harmful chemicals like diacetyl can also find its way into flavoured juices. Diacetyl has been shown to cause debilitating lung disease and is banned in vaping products in the United Kingdom.

A distinction must also be made in the use of concepts such as “healthier” and “less addictive”. It’s beyond debate that vaping exposes a user to fewer harmful chemicals than smoking, says Harding. The ingredients that make up a bottle of vape juice contain significantly less than the more than 70 carcinogens and 7000 additional chemicals in a cigarette. However, she regards that fact as something of a red herring, given the undeniable potential for addiction in new populations.

Young people’s brains build synapses faster than adult brains. Because nicotine changes the way in which synapses are formed, early exposure presents a much greater chance of addiction.

In recent times, scientists in the field of neuroplasticity have developed a greater understanding of the structural changes the brain undergoes as we learn, create memories, and develop new habits and skills. Each time a new habit is created, stronger synapses are created between brain cells. Young people’s brains build synapses much faster than adult brains, and because nicotine changes the way in which synapses are formed, early exposure presents a much greater chance of addiction to younger users.

In order to function as an effective smoking cessation aid, Harding says, vaping must be accompanied by additional counselling and behavioural support. If the end goal is to drop a nicotine habit, it’s not enough to simply switch delivery devices. Plus, she notes, by 2026, the global vaping market is expected to be worth around $45 billion. If the sole purpose of vaping is really to break the habit of smoking, at some point that growth would evaporate. “I don’t know any other business that wants people to stop buying its product,” Harding says.

And while health practitioners agree that vaping is a viable alternative to cigarettes, the industry has aggressively used that fact to market their products to a much broader customer base.

“The tactics of Big Tobacco are to obfuscate, to confuse the market, to put out a whole range of information which says ‘the research doesn’t show that’, to pay for research,” says Dykes. “They paint people who criticise vaping as extremists. They did that with smoking and I was seeing the same tactics happening in this area. They spread misinformation, they polarise the debate.”

In 2019, a Radio New Zealand investigation revealed that the work of public-health academic Marewa Glover, a prominent proponent of vaping as a smoking cessation tool, was effectively funded by tobacco giant Philip Morris. Emails released to Glover under the Official Information Act showed researchers from the University of Otago lobbied district health boards to shun Glover, the director of the Centre for Research Excellence: Indigenous Sovereignty and Smoking. Hāpai te Hauora, a Māori health-focused NGO, which holds the national tobacco control contract and advocates vaping as a smoking alternative, also declined to work with her.

A paper for the Tobacco Control journal alleged that Philip Morris had funded the US-based Foundation for a Smoke Free World to create divisions within the smoking cessation field. (Glover argued that the funding she gets from the foundation gives her the ability to do kaupapa Māori work, and that she can be more effective and independent without the backing of a university.)

Even if tougher regulations are put in place on vaping, its addictiveness and social appeal means that the rules are more of an inconvenience than an insurmountable obstacle — just as for cigarettes in the past. The critical difference is that for several generations now, nobody has been under any illusion about the safety of smoking.

Richard Dykes describes a recent visit to Glendowie College from a researcher who wanted to find out what students thought about vaping.

“We walked into a Year 12 health class and the kids said, ‘They’re perfectly safe, it’s just flavoured water’,” he says. It reminded him of something a health worker had once told him about vaping: “It’s safe only in the same sense that jumping out of a 7th story window is safer than jumping out of the 70th.”

Don Rowe is a freelance journalist and law student.

This story appeared in the April 2021 issue of North & South.