The Nazi Who Built Mount Hutt

The untold story of how a former Waffen-SS soldier lied his way into New Zealand — and got away with it.

By Andrew Macdonald and Naomi Arnold. Illustration by Ross Murray

In a lonely lodge high in New Zealand’s Southern Alps, three soldiers sipped schnapps and swapped war stories long into the winter night. It was a Saturday evening in the mid-1960s, freezing cold outside, and the middle-aged veterans were relaxing after a day spent wheeling down the ski slopes of North Canterbury. They knocked back nips at one end of the common room while other guests at the private lodge chatted around the roaring pot-bellied stove at the other. The bottle drew empty as the evening drew long.

Charlie Upham, in his mid-50s and reserved, was an infantry legend, the holder of the exceptionally rare Victoria Cross and Bar for battlefield valour in Greece, Crete and North Africa. Brian Rawson, a more sociable man of a similar age, had commanded Sherman tanks in North Africa and Italy. The third man was Willi Huber, a charismatic Austrian in his 40s with blond-brown hair and grey eyes, and he had a very different kind of war story.

Rawson, by then a banker in Christchurch, and Upham, who’d taken up farming in Hundalee, had hired Huber as a ski instructor for a few weeks at Amuri Ski Lodge near Hanmer Springs. Huber had emigrated to New Zealand in the 1950s, and told people he had been roped into the German army as a teenager — meaning he had fought for Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime in World War II. Upham and Rawson accepted this. “We might have been shooting at one another,” Rawson joked to Huber.

“Soldiers understand that soldiers get called up, and that it’s all political,” recalls Debbie Rawson, Brian’s daughter, who Huber taught to ski. To the two Kiwi veterans, Huber was just a regular “good guy”, popular with the ski-lodge crowd and one of thousands of Europeans starting a new life in postwar New Zealand. Debbie remembers the three men drinking and chatting together in the lodge’s common room, “telling jokes and roaring their heads off with laughter”.

The Austrian went on to build a name for himself in the clannish Canterbury outdoors scene as an expert skier and alpine hiker. He took an interest in people and pitched in to get things done, in the Kiwi way. His crowning achievement was helping establish the internationally known Mount Hutt ski field, which memorialised him with an advanced 821-metre ski run named Huber’s Run as well as a plaque in his honour. Huber’s Hut restaurant served Huber’s Breakfast Burger, Huber’s Smoked Salmon Salad, Willie’s Angus Burger, and Willie’s Midweek Breakfast Special. His achievements were celebrated in a string of articles over the years in local and national media that only briefly touched on his past as a “war hero” in the “German army”.

Then, in 2017, came a shocking admission: Huber told TVNZ’s Sunday programme he had served in Hitler’s feared elite guard, the Waffen-SS. This was at stark odds with the narrative he had carefully maintained for 65 years. Far from being a naive conscript, Huber had volunteered for one of the most notorious criminal organisations the world has ever known. Following the interview, and particularly after his death in August 2020, pressure mounted to strip Huber’s name from Mt Hutt.

Nearly a year after Huber’s death, his past has never been fully unravelled. Many of his stories remain accepted without scrutiny. Now, for the first time, drawing on interviews with people who knew him and official documents from archives, libraries and private collections in five countries, North & South has pieced together the life of this Nazi warrior turned Kiwi alpine legend. We discovered that the true nature of his role in the war was very different from what he claimed, and that he lied on his immigration application in order to enter New Zealand. On multiple occasions over the years, he spoke of his service for Nazi Germany with pride.

In the 1960s, Huber and Upham’s paths crossed at Craigieburn Valley Ski Area, in inland Canterbury. Huber overheard some skiers talking excitedly about the presence of a double Victoria Cross winner. He later told his friend Len Vidgen that he became quite “peeved” at all the attention Upham was getting. “He thought, ‘Fuck that, I’ve got an Iron Cross’,” Vidgen says. Huber told Vidgen that he got into his car and drove the four-hour return journey to retrieve the medal from his home in Christchurch. When he got back, he showed it to Upham: a black cross pattée of iron with a silver frame — and in the middle, a swastika.

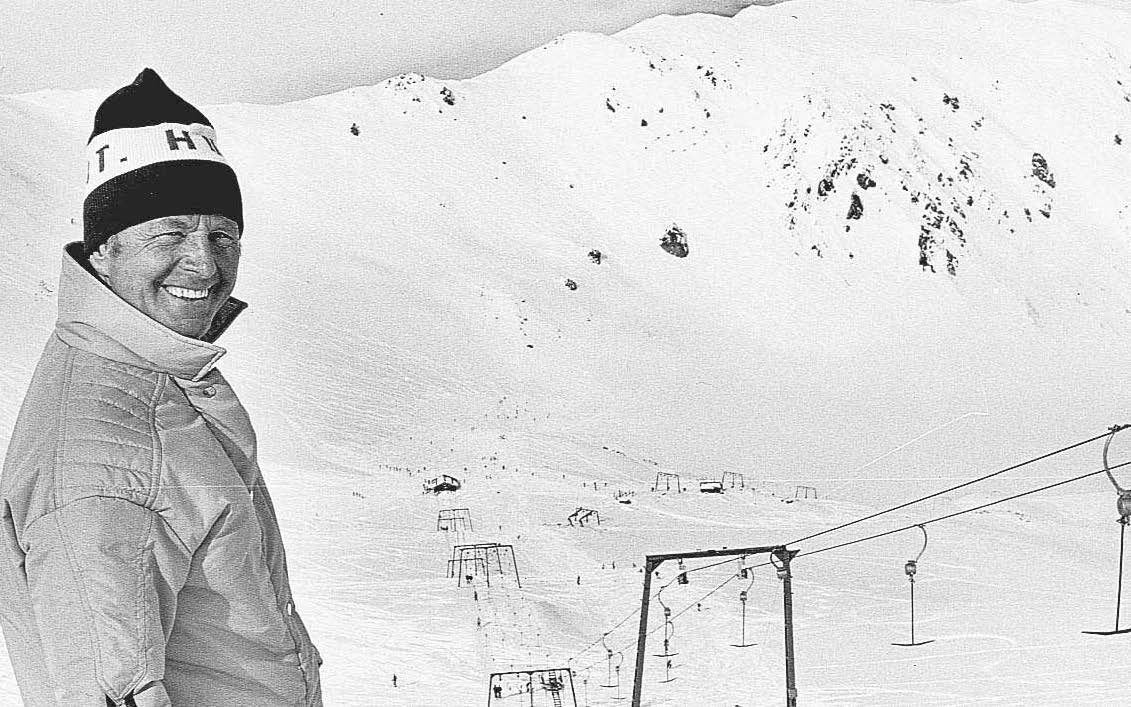

Willi Huber at Mt Hutt Ski Area. Photo: Evening Post.

Willi Huber once told a reporter that he was born under a tree, high up a mountain in Austria in the summer of 1923. His mother, Rosa, lived on her own, so Huber was raised by his father, Franz Walcher, whose farm was on the outskirts of Schladming, a small town about 100 kilometres from Salzburg.

The farm was surrounded by towering mountain peaks and snow buried the house’s ground-floor windows in winter. Raised alongside his step-siblings, Huber described his childhood as not easy, but happy. He was skiing from a young age, because that was the only way to get to school, on a trail broken by the family bull.

After Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Huber and his brothers joined the Hitler Youth, as every young person was required to do. He resisted pressure from his father to get into farming and was disinherited as a result. Instead, he spent three years training to be a mountain guide, following in a family tradition. His uncle was also a guide, and his mother went up into the Alps every summer for 52 years. Her son yearned to join her. Then, in October 1941 at the age of 18, Huber volunteered for the Waffen-SS, proudly wearing the double “S”, by then a notorious symbol of hate and death, on his tunic.

Joining the Waffen-SS wasn’t remotely the same as being conscripted or even enlisting in the German Wehrmacht (the army, navy and air force). The Waffen- SS was the elite combat arm of the Schutzstaffel, or SS — the Nazi Party’s paramilitary wing. At first a small protection squad, the SS expanded to become one of the most powerful organisations in Nazi Germany. In addition to the Waffen-SS, its constituent groups included the Allgemeine-SS, or General SS, whose members helped enforce Nazi racial policy and general policing, and the SS-Totenkopfverbände, or “Death’s Head Units”, which operated extermination and concentration camps. Other subdivisions included the Gestapo (secret state police) and Sicherheitsdienst (an intelligence agency).

The SS was Hitler’s foremost state agency of security, surveillance, and terror within Germany, German-occupied Europe and Russia. Hitler entrusted the SS with overseeing the isolation and displacement of Jews in conquered territories, seizing their assets and deporting them to extermination and concentration camps and ghettos, where they were used as slave labour or murdered. The SS was the primary player in the Holocaust, the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of millions of people in Nazi-occupied territories. According to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Holocaust was responsible for the deaths of about six million Jews, around seven million Soviet civilians, roughly three million Soviet prisoners of war, some 1.8 million non-Jewish Polish civilians, along with many hundreds of thousands of people in other groups reviled by the Nazis.

About 950,000 men served in the Waffen-SS in total. Towards the end of the war, the entry criteria were loosened, in part due to the huge number of casualties. At the time Huber joined, however, the Waffen-SS comprised a handful of top-tier fighting divisions dedicated to the vile racial ideology of Nazism. Recruits had to meet strict racial, physical and political criteria based on Aryanism, and were trained to use terror and brutality as solutions to military, social and political problems. Many members could be identified by a small tattoo on their left arm indicating their blood group. All recruits pledged absolute allegiance to Hitler. That Huber volunteered for the Waffen-SS at this stage of the war leaves little doubt that he willingly embraced the Nazi worldview.

Several tank men of 2nd SS-Panzer Division Das Reich on the vast steppe during Nazi Germany’s advance into Russia. Huber is recorded as sitting on the turret at left. His commanding officer Captain Karl Kloskowski is in the front row with arms crossed, third from left. Source: Rüdiger Warnick Collection.

After his enlistment, Huber later recounted, a call was issued for machine gunners. “So I put my hand up,” he once said to a reporter. “I thought to myself, goodness me, I think if I become a machine gunner I can go in the first row. And that’s exactly what happened.”

In April 1942, Huber arrived on the Russian Front. He began the war as a private, and was assigned to 2nd SS-Panzer Division ‘Das Reich’, one of Hitler’s premier Waffen-SS divisions. His commanding officers were highly decorated Nazi hardliners, such as Huber’s platoon and then company commander, Captain Karl Kloskowski. Sifting through thousands of German wartime photographs held in official and private collections, North & South found one that shows Huber and Kloskowski against a backcloth of the vast Russian steppe.

Huber became a seasoned combat soldier during his three and a half years with the Waffen-SS, his division fighting in major battles such as Kursk in 1943, Normandy in 1944 and the Bulge in early 1945. Waffen- SS documents show that he reached the rank of private first class and could lead small groups of soldiers. He was awarded two Iron Crosses, as well as silver badges for suffering multiple wounds and being in repeated armoured engagements.

For most of the war, Huber belonged to Das Reich’s all-tank 2nd SS-Panzer Regiment. He was a crewmember in a Panzer IV, a mainstay tank with a five-man crew: commander, main gunner, loader, driver and radio operator/bow machine-gunner. In the bitter cold of the Russian winter, the tank’s interior was “like sitting on an ice block”, a lieutenant in Huber’s regiment once recalled. In summer, the five-man crew sweated in disagreeable confinement. By the time of Kursk in July–August 1943 — the largest tank battle in history — Huber had become the main gunner, taking out Russian armoured vehicles with the tank’s 75 millmetre turret gun.

Near the end of the war, according to the diary of a Waffen-SS soldier held in a private collection in Germany, Huber’s tank was broken down or destroyed. But Huber resolved to fight on to the bitter end of the Third Reich. In early April 1945, the diary says, he was in charge of an ad hoc infantry patrol southwest of Vienna, continuing to resist the advancing Red Army. The combat was vicious and casualties were heavy. Then Huber was stabbed by a Russian soldier, the blow deflecting off his ribs into his thigh. He somehow managed to shoot his assailant.

After treatment in hospital, Huber struck out for home on roads crowded with refugees, demoralised soldiers and military transports. To be caught by Nazi security squads or military police was to risk on-thespot execution as a deserter. Ninety kilometres short of Schladming he had to go back into hospital, and while there the war ended. His bayonet injuries would still give him trouble 70 years later.

Huber spent three months at home recovering, before a disgruntled Austrian reported him to the occupying American forces. He was detained for 16 months, mostly in Italy, later describing himself as a “political prisoner”.

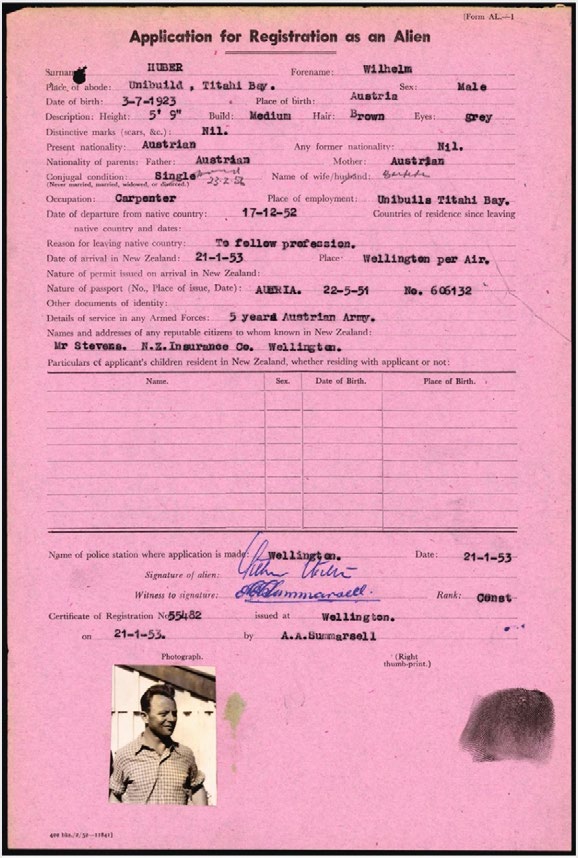

Huber’s application for registration as an alien, submitted to New Zealand Police in early 1953.

Huber lied to New Zealand immigration authorities in late 1952 when he stated in supporting documentation that he had “never been a member of any illegal organisation”. Source: MBIE.

After the war, Huber became a ski and mountain guide in the Austrian Tyrol. On one occasion, he guided an English doctor who’d spent a year at the University of Otago. The doctor told Huber about the Southern Alps and urged him to apply for a New Zealand government initiative to relieve a post-war housing shortage.

Nearly 200 Austrian tradesmen would ultimately come here to build houses prefabricated in Austria to New Zealand designs. A selection panel noted he had been recommended by the English doctor as “someone who would do well in New Zealand”.

Huber arrived in New Zealand on a TEAL flight on 21 January 1953, a few months before his 30th birthday. Approved for a two-year work visa, he applied for registration as an alien at a Wellington police station. In one supporting document, signed in November 1952 and endorsed by the District Court in Schladming, he affirmed that he had “never been a member of any illegal organisation”.

Huber’s statement was false. The 1945–46 postwar International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg had determined the entire SS to be a criminal organisation, explicitly including its individual members. The tribunal explained that throughout the SS, knowledge of “criminal activities — crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity — was sufficiently general to justify declaring the SS a criminal organisation”. The tribunal continued: “It is impossible to single out any one portion of the SS which was not involved in these criminal activities.” This, of course, encompassed the Waffen- SS in which Huber had served. The tribunal referenced the Waffen-SS’s “extensive training in questions of race and nationality” and noted that its divisions “were responsible for many massacres and atrocities”.

Under the tribunal’s charter, to which New Zealand was a signatory, Huber had three possible defences against any formal allegation of having been in a criminal organisation. That he was a volunteer and had wartime Waffen-SS service immediately disqualified him from two of these. The third possible defence was that Huber had no knowledge of the criminal purposes or acts of the Waffen-SS. Huber never had to make this defence, because no formal allegation was ever made.

In an era before databases and instant communication, immigration authorities in New Zealand — like most other countries — relied almost entirely on former Waffen-SS members coming clean in their application paperwork, which then provoked searching questions and maybe even rejection. They also placed too much store on applicants being properly vetted in their home countries.

North & South obtained Huber’s immigration records under the Official Information Act. When Huber — referred to as Willi, Willibald and Wilhelm in various paperwork — applied for a permit to enter New Zealand, he wrote that he left his native country “to follow [his] profession” as a carpenter, and, falsely, that he spent “five years in the Austrian Army”. At the Wellington police station, Constable Arthur Summarsell issued Huber’s registration documents, inked his right thumb, and he was in.

Some people who knew Huber believe he lied in order to escape war-scarred Europe for a country he perceived as idyllic. “It was his survival technique, to hide his story,” says Debbie Rawson, Brian’s daughter. And once he had committed to the lie, he had to maintain it. “He would be severely disadvantaged in every possible way otherwise,” she says.

Huber headed for Titahi Bay in Wellington and spent the next 18 months building state houses before being made redundant. One of his workmates was a fellow Austrian, now 91, who we’ll call Hans Schmitz to protect his identity. On one scorching day, the tanned, shirtless men were climbing up and down scaffolding, lifting timber beams and putting up heavy roofing, when Schmitz spied a dark-ink tattoo on the underside of Huber’s upper left arm. It was a stone-cold tell: the Waffen-SS blood-group tattoo. Schmitz recognised it instantly, because he had been pressed into Waffen-SS service as a teenager during the chaotic final months of the war.

“I was wondering how he got into New Zealand. Because, usually, they wouldn’t let people with SS [service] in,” says Schmitz. (He, too, concealed his membership when entering the country.) Schmitz asked Huber about it, and says Huber claimed to have been goaded to join by friends and family. “Look,” he remembers Huber replying, “when you are young you do some silly things.”

Builders work on one of Tītahi Bay’s Austrian state houses in August 1951. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library, Evening Post Collection (PAColl-0614).

After his work ran out, Huber borrowed $200 from Schmitz to get to the South Island, intending to climb Aoraki/Mount Cook and then return to Austria. He was waiting for clouds to clear at Mount Cook village when he met Edna May Griffith, a young woman originally from London who was on a tour of New Zealand. “What a girl!” he thought. They married in 1956 and settled in Christchurch, where Huber worked various jobs, including as a salesman of outdoor sporting equipment.

“In no time Huber came to know more about New Zealand’s mountains than many of his contemporaries,” wrote Gerry Power in White Gold: The Mount Hutt Story, an exhaustive history of the ski field. “His mountaineering exploits became the stuff of legend.” Huber eventually lost count of the number of times he summited Mount Cook. He made the first traverse of the Arrowsmith Range from East Horn to Jagged Peak. He helped build Haast Hut below Mount Cook. “I knew mountains better than I knew anything else,” Huber said in the book.

In 1969, the Methven Lions Club enlisted Huber, as well as Himalayan mountaineering veteran Geoff Harrow and skier Noel Chambers, to check out Mount Hutt’s Pudding Hill Basin by helicopter, with an eye to building a ski field. When Huber saw the basin, covered in a night’s fresh snow, he knew they’d found the right spot.

In late April of 1971, he moved into a one-room, reddish-brown wooden hut he had designed, built on the northeast side of the basin at around 2000 metres altitude. The four-by-eight-metre dwelling was soon dubbed Huber Hut.

Anchored to the mountain by rock-filled wire nets and wire guy ropes, the hut was often freezing, thanks to a temperamental diesel heater. But Huber relished the solitude. He took meticulous records of wind, sun, temperature, snow, and weather conditions, helped during the school holidays by his teenage son Antoni.

On one occasion, three young men were bringing him a radio and became disoriented in a sudden onset of bad weather. Huber didn’t know they were on their way, but Antoni heard their voices calling for help.

With the storm setting in, Huber grabbed alpine gear and followed the increasingly desperate cries. He found the three men huddling in whiteout conditions, lightly clothed with temperatures hitting -5 degrees Celsius. One was beginning to lose consciousness. He shouted at them to get up, but the boy was in a particularly bad way and couldn’t follow his instructions. Eventually, Huber punched him and yelled “If you don’t move, you’re going to die here!” Roped together and guided by Huber, the young men made it to the safety of his hut.

But for the five months Huber spent on the mountain, he was mostly alone, except for two field mice he named Ferri and Mary. He fed them, and they returned night after night and stayed for hours, looking up at him with large round eyes as he wrote up the day’s measurements. One night, when the temperature fell to -12 degrees Celsius, the mice didn’t show. Huber slept restlessly until he woke up in the middle of the night and went searching. One was already dead in a corner, and he took the other into his sleeping bag to try and revive it. But it was too late.

It was the last peaceful winter on the mountain. After five months, Huber came down, armed with his sheaf of records. He had discovered that 80 per cent of the days were skiable, with negligible avalanche danger in the basin. Mt Hutt Ski Area officially opened in 1973, with Huber as field manager.

A photo of a report on the suitability of Mt Hutt as a ski field, featured in the same display. Photo: Naomi Arnold.

A replica of Huber Hut at Methven’s NZ Alpine & Agricultural Encounter. Photo: Naomi Arnold.

In the years that followed, the mountain became important to the Methven community, intertwined in Canterbury sport and social history. And Huber became Mr Mt Hutt, known for yodelling down ski runs and for his exacting ski instruction.

“He was a larrikin,” says his friend Len Vidgen, who got to know him well in the 1970s. “He was a storyteller and an entertainer and a fun-loving person. He wasn’t a complicated guy. He was a mountain man.”

Huber rarely said much about his war service, and when he did, the stories varied. He told Vidgen that he had belonged to some kind of super-elite alpine commando unit — part of an army “Special Services” branch that he said “had nothing whatever to do with the SS that most people understand as the SS”, Vidgen recalls.

“He certainly wasn’t the sort of person that would cause any blues or grief or anything like that,” Vidgen adds. “He just wanted his bloody ice axe and crampons and skis, and the rest of it could go to heck as far as he was concerned.”

Throughout his life, Huber was the subject of many feel-good stories. In newspaper profiles in the 1990s in The Press, Otago Daily Times and Ashburton Guardian, his war record and Waffen-SS membership weren’t mentioned. Neither was it referenced in White Gold. The colourful anecdotes making up the story of his life fit perfectly into the DIY, outdoorsy narrative we like to tell ourselves about the Kiwi character.

Huber began to open up more in his 90s. In a 2014 profile, Mike Crean of The Press characterised him as a decorated war hero in “the German Army”. Huber claimed he had volunteered because he knew he would be conscripted anyway, and he wanted some choice about where he was stationed. But it wasn’t until the 2017 documentary on TVNZ’s Sunday television programme that his history attracted any real attention. Interviewer Cameron Bennett described Huber as “a remarkable survivor”, one of the world’s last living Waffen-SS soldiers. But instead of pressing Huber on his decision to volunteer for this notorious organisation, he mostly focused on Huber as an alpine pioneer. Bennett probed Huber only lightly about his past as a soldier of the Nazi regime. As for Huber, instead of condemning Nazism, he spoke with glowing pride of seeing the Führer in person.

“I saw Hitler when I was 9 years old,” he said. “Could you imagine?” he added, beaming. “He was smiling, he looked at us, put his arm up [in the Nazi salute] as he always did.”

Huber explained that Hitler “offered a way up” to starving Austrians after the World War I. “I give it to Hitler — he was very clever,” Huber said. “He brought Austria out of the dump.”

Bennett asked the avuncular old man if he, as a Waffen-SS soldier, was aware of the Holocaust and crimes against humanity.

“Never. Never. I only can say we were soldiers. Never, never had the slightest inkling . . . maybe the High Command. Us, boys, it never occurred to us what happened in Germany or what happened in Poland and all these places.”

Bennett: “Because of course there were the concentration camps — you didn’t hear anything about this?”

“Only at the bitter end we saw a lot of Russian prisoners marching past us and realising they’re all half-starved already,” Huber said. “But about the Jews, we never got educated about it in any way about the Jews . . . We had no idea about the concentration camps.”

In the broadcast interview, Bennett had to ask several leading questions to get even a hint of empathy out of Huber: “And when you learnt about this [the concentration camps] were you horrified?” Huber produced only this pat rejoinder: “What could we do? We all agreed it is wrong but that is about all. You couldn’t do anything about it anywhere.” It was a hint of admission that Huber actually did know what was going on. And then the moment passed.

After the show aired in August 2017, viewers posted nearly 400 comments on Sunday’s Facebook page. Some said that they felt physically ill as they watched it. Others defended Huber as just a country teenager swept up in the war.

In the Listener, Diana Wichtel pointed out Huber’s striking lack of condemnation for either Hitler or the Holocaust. “If he was horrified by what happened, he didn’t say so,” wrote Wichtel, whose book, Driving to Treblinka, chronicled her search for her lost father, a Polish Jew. “Joining the SS wasn’t such an obvious choice as Sunday seemed to unquestioningly accept. Huber was very young when he joined up, but he’s had a lot of time to think. Here was a chance to ask some penetrating questions.”

This year, TVNZ removed the documentary from its website. “We accept this should have been more robust,” TVNZ’s general manager of corporate communications, Rachel Howard, says of the piece now. TVNZ wouldn’t provide a copy to North & South (we viewed it several times before it was deleted) and said Cameron Bennett was not immediately available for comment.

We also contacted the Huber family on multiple occasions. Edna Huber referred enquiries to her son Antoni, who said on behalf of the family that it was still coming to terms with Huber’s death and didn’t want to comment or take part in this story.

A photo of an image of Willi Huber’s mountain hut under construction in the early 1970s. The picture is displayed at Methven’s NZ Alpine & Agricultural Encounter. Photo: Naomi Arnold.

Soon after Huber’s death, human rights groups and the Jewish community called for his name to be stripped from Mt Hutt Ski Area. Manager James McKenzie said that unless evidence emerged that Huber had participated in war crimes, it wouldn’t be changing the names. “We are happy to respect his legacy,” McKenzie told Stuff. “The context of what he went through in the war, nobody knows for sure what people did way back then.”

In seven months, nearly 7000 people signed a petition demanding that NZSki, which owns the ski areas at Mount Hutt, Coronet Peak, and the Remarkables, remove Huber’s name from its various locations — a ski run, restaurant, and memorial plaque on the site of his old hut.

We will never have a full recounting of what Huber saw, what he did and what he thought while in the Waffen- SS. However, North & South gained access to copies of thousands of period documents, Huber’s personal Waffen-SS and prisoner-of-war files, several books, and the diary of a Waffen-SS soldier who knew him in April and May of 1945. These materials reveal the dates and locations of his unit’s whereabouts from 1941 to 1945, allowing us to assemble the most detailed picture yet of his military service.

On a late-spring dawn in France, 8 June 1944, the tanks of 2nd SS-Panzer Division ‘Das Reich’ roared into throaty life. It was two days after the D-Day landings in Normandy, and the division had been ordered almost 700 kilometres north from its billets around Montauban in southern France to consolidate Hitler’s grip on Europe.

On 7 June, French freedom fighters had seized the southern town of Tulle. The next day, en route to Normandy, Das Reich took it back. In the fighting, some 40 soldiers from the German garrison were apparently murdered and mutilated. A coterie of ruthless Das Reich officers decided to issue a stark warning.

“We have developed on the Russian Front the practice of hanging. We have hanged over a thousand men in Kharkov and in Kiev,” Waffen-SS executioner Aurel Kowatsch told one eyewitness. On 9 June, Waffen-SS soldiers hung 99 of the town’s men from lampposts and balconies. “This is nothing to us,” boasted Kowatsch. A crowd of roughly 500 was forced to watch.

Witnesses spoke of Waffen-SS goons taunting the men and bashing them with rifles, and of botched hangings in which the executioners simply swung from their victims’ legs until their necks snapped. A few small groups of Das Reich men looked on, drinking wine as a gramophone played. Some accounts say the hangings only stopped because the henchmen ran out of rope. The bodies were taken down later that evening. A further 149 men from Tulle were deported to Dachau concentration camp — only 48 came home.

Das Reich’s armoured column was spread out over the kilometres of road leading into Tulle. Huber’s tank was among them; on at least one occasion he mentioned being present on the sluggish journey from Montauban to Normandy. His tank passed through the village, probably on 9 June, the same day the hangings took place. Knowledge of the reprisal in the small town and within Das Reich was commonplace, and it seems probable he would have seen the limp corpses dangling from ropes.

A day later, on 10 June, a company of Das Reich’s infantry razed the village of Oradour-sur-Glane in France. They killed 642 civilians, apparently as retribution for the killing of a Waffen-SS officer. The village was never rebuilt and remains a memorial to the cruelty of Nazi occupation. According to Das Reich documents from the period and various detailed publications about the atrocity, Huber’s tank must have passed within kilometres of the smouldering ruins.

North & South has scrutinised Huber’s Waffen- SS file, released after a formal request, and other documents leaked by a source in Germany’s Bundesarchiv, or national archive. It seems highly unlikely that he was a triggerman at any mass-murder sites synonymous with the Holocaust. There is no mention of him being a guard at extermination or concentration camps and no reason to believe he was one. However, while Huber didn’t personally participate in the heinous crimes at Tulle or Oradoursur- Glane, it remains unclear whether he and his battalion were involved in crimes and reprisals against civilian populations elsewhere.

For instance, in a 1981 book about Das Reich’s bloody trek to Normandy in mid-June 1944, British journalist and military historian Sir Max Hastings outlined a string of the division’s brutal responses to real or perceived acts of resistance. From May to June 1944, Huber’s tank battalion was camped in the south of France. Across an alphabet of villages and communities northeast of Montauban, Das Reich rounded up and deported more than a thousand civilians, executed some 20 women and men, and left hundreds of other villagers as refugees. They burned buildings and looted shops and homes, all of it as revenge for acts of resistance committed by people living under the jackboot.

“In those last weeks before D-Day, the 2nd SS-Panzer Division made the price of Resistance very clear to the surrounding countryside. Reprisals were on a scale modest enough compared with Russia, but thus seemed savage enough at the time,” wrote Hastings in Das Reich: The March of the 2nd SS-Panzer Division through France, June 1944.

Hitler’s worst henchmen lit fires under piles of decomposing bodies. The stench was pervading and the columns of smoke would have been unmistakeable.

Huber’s precise role in all of this, if any, is unknown. It is clear that Das Reich’s non-infantry troops were periodically instructed to patrol the countryside to demonstrate strength and undertake counterresistance activities. As Hastings notes, on 2 May 1944, one of the division’s tank battalions was involved in the sacking of Montpezat-de-Quercy. On 1 June 1944, another Das Reich tank unit machine-gunned six civilians in Limonge, one at Cadrieu and two at Frontenac. Das Reich’s tank battalions were a small part of the division, and it was in one of these that Huber served as a gunner.

Lichtner notes that atrocities on the Russian Front included thousands of mass murders and executions targeting Jews, communist party members, local administrators and the Roma and Sinti peoples, among others. In 1943–44, Hitler’s worst henchmen lit fires under piles of decomposing bodies, attempting to cover their grisly crimes. The stench was pervading and the columns of smoke would have been unmistakeable.

“He would have travelled through places where two million Jews lived, more or less, and who didn’t live there anymore when he arrived. The hole that that population left would have been absolutely massive,” Lichtner says.

In late 1943, Huber’s unit entered the Ukrainian city of Berdichev. Before the war Berdichev had been a thriving city of about 60,000 people, about half of them Jewish. By mid-1942 the Jewish population had been almost entirely liquidated in a number of SS-led operations. Most tallies estimate that around 30,000 Jewish children, women and men were murdered and dumped in bloody, foul-smelling mass graves.

“All is silence. Everything is still. A whole people has been brutally murdered,” lamented Soviet author and journalist Vasili Grossman whose wartime notebooks were published as A Writer at War in 2005. The mass graves, he continued, were anything but invisible: “The earth is throwing out crushed bones, teeth, clothes, papers. It does not want to keep secret.”

As Lichtner says, “The idea that he [Huber] couldn’t have known, or didn’t know what happened to them, is ludicrous.”

A tank crew from 2nd SS-Panzer Division Das Reich after the 1943 Battle of Kursk in Russia —the largest tank battle in history. Source: Reddit.

The local hall in Methven, the closest town to Mt Hutt Ski Area, is also a community centre, war memorial, and ski museum. Inside, in the New Zealand Alpine & Agricultural Encounter, there’s a replica of Huber Hut containing his skis, bed, a photo of his family out hiking, a stove, socks, and other alpine paraphernalia.

When North & South visits in March, we run into Viv Barrett, a farmer and horse-breeder known as “the unofficial mayor of Methven”. Barrett, a spirited and friendly fellow who wears a series of battered caps, was a friend of Huber’s. He takes us inside the hut, pointing out the two stuffed toy mice on the table representing the small souls Huber befriended. The name “Huber Hut” won’t be coming down, Barrett says, adding a couple of choice words for emphasis.

Many locals we speak to are angry about the campaign to have Huber’s name taken off the mountain. They say the 7000-signature petition was mostly internationals with only a few hundred Kiwis. (In fact, 46 per cent of the signers were from New Zealand, with 27 per cent from the United States and 16 per cent from Australia, no small factor given that Australians make up around a third of visitors to our ski fields.) Over and over again, people complain that Huber has been the victim of “a hit job” by the media and that his critics just don’t realise how much he has contributed to Mount Hutt and to the entire New Zealand alpine community. One local said, “It’s all those Jews complaining, is it?”

Barrett is a true community man. At 89, he’s been on the hall board for 60 years, and nobody slips past his radar. On the day we met him, The Press runs a Newsroom story reporting that NZSki has finally decided to strip Huber’s name from his ski run and rename the restaurants. In addition to the pressure from human rights organisations and Jewish groups, the Rainbow ski community had voiced concerns; the Winter Pride festival involves NZSki’s other two resorts, Queenstown’s Remarkables and Coronet Peak.

Facing a publicity disaster, and after sounding out various groups including the Huber family, the Human Rights Commission and some local RSAs, the company announced that the time had come to let the name go — a statement at odds with its previous proud defences of Huber’s legacy. The name Huber’s Run would be removed from the trail (it has already been erased from the 2021 Mount Hutt ski map) and Huber’s Hut restaurant would become Ōpuke Kai — Ōpuke being Ngāi Tahu’s name for the mountain.

James McKenzie told North & South that the furore over Huber has caused a lot of hurt to staff and supporters of the mountain. He downplays the significance of the name changes, saying Huber’s Run was confusing from a customer perspective anyway since it ran next to an existing trail, and that the restaurant was only renamed Huber’s Hut in 2009. “Out of respect to the family we have kept our commentary around decision-making very low key,” he says. “It was a real learning process to go through but I think we have the balance right.”

Barrett is indignant. “Why wait until he’s dead to raise all this, when he’s not here to defend himself?” he says. (Huber didn’t publicly respond to the questions raised after the Sunday programme in 2017). He takes North & South to visit Jo and Ernest “Butch” Stern, friends of Huber and his staunch defenders.

Jo and Butch own Mt Hutt Lodge, a beautiful, cosy place built on wide terraced steps carved over the centuries by the powder-blue Rakaia River. Huber celebrated his 90th birthday here. The hallway is plastered with newspaper clippings and mementos, including a memorial photo of Huber in formal Austrian dress wearing a state honour from his birth country, a Gold Medal for Services to the Republic of Austria, for fostering links with New Zealand. Also pinned up is an editorial in support of Huber that appeared in a local newsletter called Snowfed. (The editor, Annie Jacobs, received hate mail accusing her of being a “Nazi lover/ Hitler lover”.)

Jo, a pioneering skier and instructor, was Huber’s friend for more than 40 years, starting at Mount Hutt when Huber was ski-field manager. Butch is a former professional surfer turned chef. He is also Jewish.

“Willi’s pictures will always stay on our wall,” Butch says. “Willi’s cabin will always be in the Methven hall. Willi’s plaque will always be up at Mount Hutt.”

Butch pours us a Coke, spreads his palms out on his bar, and sets to talking.

“My parents were refugees from Hitler,” he says. They left Vienna in 1938 for the United States, and he still has their Nazi-era passports, emblazoned with swastikas. He goes to get them and lays them on the bar. They were issued in “Vienna, Germany”, and both are stamped with a giant red J, for Juden.

Many locals are angry about the campaign to have Huber’s name taken off Mount Hutt. One said, “It’s all those Jews complaining, is it?”

In October 2020, Butch wrote a letter to Snowfed expressing support for Huber. He acknowledged that he had experienced anti-Semitism, describing it as “bred-in” to the community. But Willi Huber’s legacy to “our country, our island, our town and our mountains is one of love and caring,” he went on. “While many of my family died in the Holocaust, it wasn’t Willi’s fault.” He’s the only person who could write a letter for Willi like that, he says. Because he has those passports.

“We didn’t know he was tied up with the war or anything else,” Jo says. “You take people as you find them.”

“He was always there for everybody,” Butch says. “Everybody at Mount Hutt will always remember Willi fondly.”

The three agreed that you can’t blame a young man for being drafted into the war. We point out that Huber volunteered — and not for the regular army, either.

Jo says, “Could we look at it [another way] too: at that time, was the German Nazi Party known as the horrific Nazi Party?”

We ask if they’d known Huber was in the Waffen-SS.

“He never talked about it,” Jo says. “When he talked about Austria it was always about mountains, and skiing . . . You’re not going to sit down in Huber’s Hut and say ‘Now, Willi, tell us what happened’.”

“I don’t think Willi was hiding anything, it’s just that people didn’t talk about the war,” she continues. “You talk to most of our old soldiers and none of them talked about war.”

At one point, Barrett explains that people around Methven didn’t know anything about Huber’s war years until “that bloody programme”, by which he means the Sunday interview.

“It’s typical journalism,” agrees Jo. “It’s like Jack Tame, zooming in on something that’s almost irrelevant.”

“There was much too much about the war asked of him, instead of the names of his pet mice up at Mount Hutt and that kind of thing,” Butch says.

We tell them that Huber got into New Zealand by saying he was in the Austrian army, and they laugh.

“He told a wee fib there, did he?” Barrett says with a chuckle.

“Well, either way,” Butch says, “in the end, what he did for this area, is, more than anything, a lot more than what’s happened [in the war].”

The conversation is friendly and relaxed, and it’s obvious how deeply affection for Huber runs around here. We ask what the mood has been like since all the “hit jobs” came out.

“Everybody still loves Willi as Willi,” Butch says. “As far as we know, nobody’s said ‘hang the Nazi’. I heard a couple of people in Ashburton weren’t too happy, but that’s their problem . . . I actually lost all my family, except for my mother and father, in the camps. But Willi was a friend.”

Butch Stern’s parents fled Nazi Germany. Their passports are stamped with a red “J” for Juden (Jews). Photo: Naomi Arnold.

To what extent should Huber be held responsible for his choices when he was a very young man? Even if you take the most sympathetic view — that he was a teenager caught up by forces he didn’t understand — it’s revealing to compare his reflections later in life with those of two other former Waffen-SS members.

One is the Nobel Prize-winning German author Günter Grass, a late-war conscript who spent two months on the front line. As a writer, he became known for his eloquent denunciations of Hitler and Nazism. But it was only in his 80s that he publicly grappled with his grief and shame over his Waffen-SS membership. That he was forced into combat as a young man was no excuse, he said.

“The ignorance I claim cannot blind me to the fact that I had been incorporated into a system that had planned, organised, and carried out the extermination of millions of people,” Grass wrote in a 2007 New Yorker article. “Even if I could not be accused of active complicity, there remains to this day a residue that is all too commonly called joint responsibility. I will have to live with it for the rest of my life.”

Or, much closer to home, consider “Hans Schmitz,” the former Waffen-SS member who worked with Huber in Tītahi Bay. Schmitz retains a strong Austrian accent even after living here for almost 70 years. (He is now a New Zealand citizen.) He says that at 15, he was one of thousands of teenage boys and old men conscripted into the Waffen-SS to meet the advancing Allied and Russian armies in April–May 1945, as the Third Reich collapsed into oblivion. He served only in Austria. If accused of being in a criminal organisation, Schmitz’s defences, according to Nuremberg trial documents, were that he was a late-war teenage conscript and had — in part because of his brief service — no knowledge of its criminal purposes or acts.

As Schmitz tells it, the hotchpotch battalion he was placed in wasn’t at all like Huber’s unit of rampaging ideological warriors. He is forthcoming about his service and what he saw. He says straight out that he regards the Nazis’ genocidal actions as horrific. “Hitler was a megalomaniac, ridiculous and horrid,” he says.

Huber, in stark contrast, never openly rejected Nazism. Nor did he publicly acknowledge that he was part of a criminal organisation inextricably linked to the Holocaust. He lied about his service for decades. Even after admitting Waffen-SS membership, he denied knowledge of the war crimes, atrocities and genocide committed by Hitler’s war machine. In effect, he denied the “joint responsibility” of individuals, accepted by Günter Grass and set out at the Nuremberg trials. If Huber had sincerely spoken out against Hitler and the Holocaust, if he had shown contrition for having been a tiny cog in a genocidal machine, there is a chance his name might still be up there, on the mountain.

A Christchurch woman, who doesn’t want to be named for fear of drawing the ire of far-right groups, knew Huber as a family friend throughout her childhood. When she was in her teens, she vividly recalls hearing him say at a gathering of Kiwis and Austrians that “Hitler really wasn’t that bad, you know.” Nobody reacted, she says, but “he knew there were people in the room who wouldn’t like that”.

The woman says she felt ill as she watched an animated Huber show off his Nazi medals and badges.

Later, in 1980, the same woman was working at a Jewish-owned shop in central Christchurch when Huber walked in. He wanted to sell Nazi regalia to a staff member who collected wartime German memorabilia. The woman says she felt ill as she watched an animated Huber show off his photographs and Nazi medals and badges.

She says she once challenged her parents, asking why they were friends with a Nazi. As she recalls, her mother replied: “We just accepted people when they seemed nice.”

This succinctly captures the attitude of so many Kiwis who encountered Huber. Their personal experience of him as a “good guy” seems to have far outweighed even passing interest in whatever he might have done in the past. “I don’t think he had a conscience. And I think we allowed him to not have a conscience,” the woman says.

For all the questions that remain about Willi Huber, his story also raises some uncomfortable questions about the country he made his home. Why did so many people avoid looking too hard at Huber’s past — or looking at all — as if they didn’t want to know the answers? Are we perhaps just a very forgiving, docile, sleepwalking sort of people — “smiling zombies”, as Gordon McLauchlan famously called us in his 1976 book The Passionless People?

Deb Hart, chairwoman of the New Zealand Holocaust Centre, expressed surprise that “there was just such a low level of understanding about what Mr Huber was” — especially given how many of our soldiers fought and died to defeat Nazism in World War II.

And yet this isn’t the only example of New Zealand being apparently unwilling to weed out or confront Nazis after the war’s end. In the early 1990s, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a US-based Jewish human rights organisation that has helped track down people potentially involved in Nazi war crimes for prosecution in various countries, handed the New Zealand government a list of some 40 such suspects who’d arrived here during the 1940s and 1950s. Police ran an investigation but no prosecutions were attempted. As Efraim Zuroff, Nazi hunter and director of The Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Israel office, said, “There was absolutely no political will to take legal action”.

Immigration New Zealand (INZ) did not investigate Huber’s television disclosure about his service in the Waffen-SS, a spokesperson for the department says. It had “no record of the disclosures made by Mr Huber in the media being brought to our attention, and we have not received a subsequent formal complaint on this matter.” The INZ spokesperson said that there was now no action it could take, given that Huber had died.

Separately, a spokesperson for the Department of Internal affairs confirmed that Huber had never applied to be a New Zealand citizen, a process that would have ostensibly involved further vetting, including questions on whether he had participated in war crimes.

There can be no doubt that Huber contributed much to New Zealand as an immigrant, worker, family man and ski pioneer. It is equally true that in lying to immigration authorities in order to live in New Zealand, he committed a significant dishonesty offence. Some will say that Huber did disclose his time in the Waffen- SS. But this admission came at an age when there was almost no chance he would be deported.

Willi Huber had a wonderful life here. Fit and spry, he skied well into his 90s. Along with Edna, he nurtured an accomplished family, including four children and many grandchildren. He was a beloved member of a warm and supportive community. He lived a lie, and he got away with it.

A few years before he died, in a profile for Stuff, Huber reflected on the nature of memory. He was finding it more difficult to remember the present, he said, but his recollection of the past was still strong.

“I’m quite happy anyway,” he said. “Life was good and I was lucky.”

Andrew Macdonald is a military historian and author. Naomi Arnold is a senior journalist at Radio New Zealand and former contributing writer to North & South.

This story appeared in the June 2021 issue of North & South.