A Space For Life To Grow

The anger and anxiety of the fertility game.

By Michelle Langston

Illustrations by Imogen Greenfield

The fertility specialist smiles and tells me I have the kind of healthy-looking uterus she likes to see, and then tells me I’m probably generating only a couple of good-quality eggs each year. It’s not until a few moments later I feel the impact of this blow, feel it make contact with my heart, then bury its weight in my womb. I am still back at the positive news about my nice uterus. Two eggs, maybe three. That’s it, that’s all, in a year.

The office is set up so that my chair directly faces her, the corner of a desk between us. Arun has to sit on a couch behind me; I can’t reach out to him unless I extend my arm back at an awkward angle and dislocate my shoulder. It’s like being offered up to a judge who will decide my fate. She reads the information we have supplied back to us in a careful, neutral tone: “Michelle, you are a 40-year-old woman.” There is a short pause, and I think more is coming, but instead she swivels in her chair to face my partner: “Arun, you are a 33-year-old journalist and physiotherapist.” It appears that my career has no relevance here; I am a vessel only. I am the sum of my parts: a visually pleasing reproductive system and more low-quality eggs than good ones. While she talks, I feel the room stretch out of shape, and warp to fit every woman who has sat here before me, and who is lining up to come after. It’s so perfunctory I have to remind myself of where I am. This is not a meeting with a bank manager; this is a meeting to check about having a baby.

We move on to sperm results; we talk about motility, my age (again), and making the most of chances. When we say we will not be pursuing IVF (we can’t afford it, and I am too old to qualify for a free round; we also can’t face the miseries we have witnessed in friends), I see her expression change. It is almost imperceptible, the shift that rearranges her features to those of someone who now invests just slightly less. This is the game, of course. This is fertility, where we all run the race; the win is a baby, or you run forever, getting nowhere. Without IVF, we cannot run so far or so fast. Intrauterine implantation — IUI — is our option, and could boost my chance of conception across a few cycles, though its success is more modest. We are not the serious contenders we might be. Still, when the specialist describes the way the sperm gets washed and sorted before being inserted close to a matured egg, I think about lots of cheery souls fresh from a bath, towel-dried and friendly, and I find myself lifted. Should we need it, I could bear it. We move on.

It’s not that our fertility doctor is cold, it is not that she is unhelpful or unsympathetic, it’s that she is incurious about who we are. Because we are unexceptional: we are two of many, part of the nebulous form from which hopes appear in the shape of babies like misty clouds separating out from the collective consciousness of all who visit these rooms. This is our baby dream coaxed from the air, and it is just one of hundreds and hundreds. We, wistful, wanting, wear our hearts on our sleeves. Surely she notices them beating in front of her. Her eyes range over our blood tests and sperm results; she wields the ultrasound probe with deft precision, and peers at the screen with great concentration, and she examines my partner’s testicles with humorous efficiency, but she does not look at our hearts. Perhaps she can’t let herself. I tell myself this detachment is a protective mechanism from the weariness of caring too much.

We leave with instructions to have sex as much as we can, because ovulation is imminent. We sit in the capsule of our car not entirely sure what just happened, and go home and hang up the keys and take off our clothes. We start giggling and can’t stop. We feel oddly like children — naughty, furtive. I laugh until I cry, and then I sniff for a bit while we have sex. It feels like our doctor is watching us like an omniscient fertility god, nodding at our achievement.

It’s all I can think about over the following days, this schedule of reproduction. I am confident we will get pregnant. On paper and on the glowing screen we look good, and we are up for the job. Though we have tried for a few months before this, somehow the new knowledge we have means we’ll achieve pregnancy, because we understand exactly what is happening, and when. We will have the sex, we will lie down for no less than 15 minutes afterwards, we will continue to take our supplements, and we will be pregnant in a few weeks.

I think about that first day and remember how long it took to take off our jerseys and socks, and how we gathered the winter duvet around us for warmth as we lay there, checking the time, checking the pillow jammed under my bottom to tilt my pelvis, talking about work, about our cat, about the future. Now we are deep in another autumn, and the air is heavy with damp, and my body is heavy with the things that don’t happen to it month after month. Almost a year has gone by. I don’t know where we are.

I find it insane now to think about how terrified of getting pregnant I was when I was younger. The panic when contraception broke, the rush to the pharmacy for a pill to make everything better, the endless years on drugs to prevent life. I was so studious about avoiding the situation I now covet. When I look at the statistics, it seems miraculous that anyone gets pregnant at all. According to the reading material that eyeballs me from the kitchen table, each natural cycle I go through provides me approximately a five per cent chance of pregnancy. A decade ago I had about a 20 per cent chance. My fertility has slipped away quietly, like a boat slips its moorings and drifts, found later where it shouldn’t be, worn down and rusted.

I think about the sex ed talks we had at intermediate school when I was 11, and how they explained our periods to us, and how we left clutching samples of tampons and pads, feeling radiant with our own biology, feeling secretive, and bestowing the boys in our class with mysterious smiles because of this gift we now had, this ability to bleed or grow life every month. The things we were now capable of were dazzling. We felt the power in our bodies, and we paraded our new knowledge around the netball courts at lunchtime, and crunched in groups under the trees, taking apart the little gift packs of sanitary products, admiring their order and practicability. Watch out for unprotected sex, the brochures lectured. Watch out for pregnancy. Now here I am, half a world away and desperate to be irresponsible.

She examines my partner’s testicles with humorous efficiency, but she does not look at our hearts.

The first time I got my period I felt exactly as I feel now: disappointed and sore. Mum excused me from the table, and took me away to the bathroom. I suppose she saw how uncomfortable I was — I’d been complaining of a sore stomach all afternoon. I walked out of our kitchen, left my spaghetti and meatballs wallowing on the plate, and felt the shift in my life. Even though I was joining a club, and finally in the same league as my older sister, who seemed so knowing and so cool, I had the sense that I had lost something. I had responsibilities now. I had tipped over into the next part of my life and there was nothing I could do about it.

Now, too, I bleed and feel disappointed and sore, and I know I am tipping over into the next part of my life — into my middle age. I can’t slow it down, and I can’t prevent it. One by one my eggs leave my ovaries for a brief dance through my body, and when they are not solicited for further activity they break down, and are shed, little ghosts of the lives they could have been, gone. Someone once told me that you only have a certain number of heartbeats assigned to your body for your life. I don’t want to know if that’s true, but I think of them running out the way my eggs are running out, and these days it feels as if my heartbeats hold hands with my eggs and they leap off cliffs together and vanish.

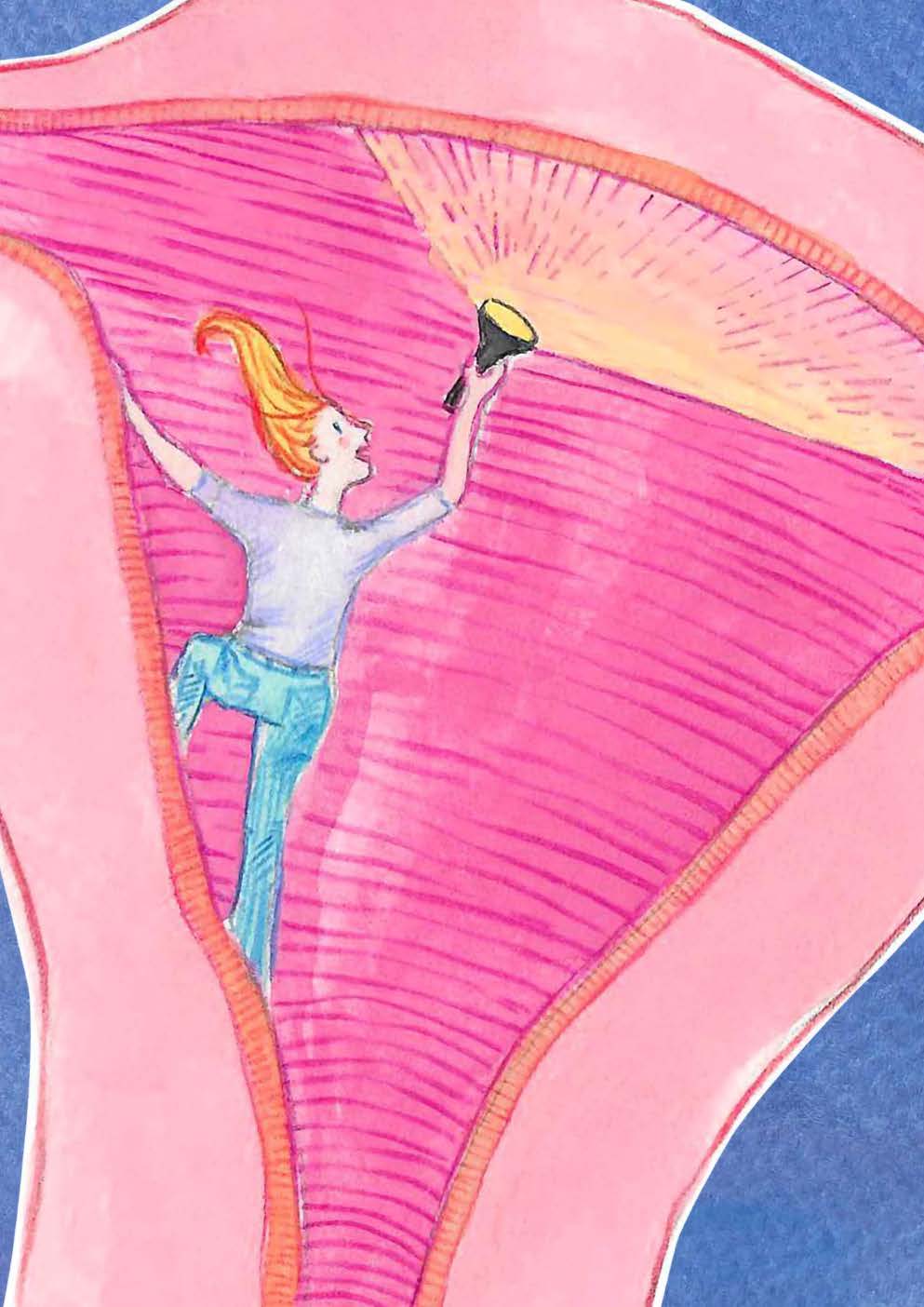

Because I have a series of ultrasounds, I can discern the shape of my uterus as it pulses in and out of shadow on the little monitor. My womb looks like a cave, and the wand of the ultrasound is the flashlight of an explorer, sending light across the walls, looking for the ancient information my body stores on its insides. At one point when they are trying to flush me with dye to check for blockages, I scream in pain and we have to pause while I fight not to faint. I go home and I look up anatomical images of the uterus, and look at the cervix and feel staggered there was equipment anywhere near it. These images are much more detailed than the slick drawings that accompanied our talks at school — every part of the female anatomy is carefully labelled and explained. That’s when I learn the cavity in the uterus is called the lumen. I study the ovaries which appear hung at the end of the fallopian tubes like buckets. I’m reminded of the way people carry pails of water from a wooden yoke strung across their shoulders. I visualise myself walking, and see eggs spilling out of my ovaries like water sloshing over the rims of the buckets and scattering everywhere, wasted.

I have lost count of how many people uttered the world’s least helpful phrases: “It will happen when it’s the right time” and “You just need to relax and it will happen.” I cannot calculate my frustration when I hear those words. I want to explode like a dropped vase and litter the room with glass, I am so dangerous with anger about the insipid and lazy use of language. It is as lovingly misguided and infuriating as the phrase “Everything happens for a reason.” Reason has nothing to do with it. Everything happens. That’s it, that’s the end of the statement.

(I am angry often.)

When my dad died I was angry that someone so good could have it so bad, and have to leave. I was angry that so many indecent humans were thriving, and my best one declined and I couldn’t hold on to him. Now I feel angry at the words said by people who have never had anything bad happen to them, and who don’t know how to listen with empathy, even though I know we are all trying to find meaning or hold on to some kind of faith in this life. I’m angry that I had to wait so long to find my love, that I may not be able to have his child. I am angry at my body, which I do not understand, even though I try so hard. I am angry at myself for being angry; angry at the trap I find myself in where the anger causes stress, which in turn causes fear that I will not conceive because of the stress.

Every time I get anxious, which is often, I feel the element turned to the hottest temperature inside me, and before I can stop it I see the contents of my womb incinerated in a flash of heat. I lose sight of the rare miracle of love that has arrived in my life, late but perfectly formed. I forget to appreciate the good fortune of finding him, obsessed as I am with what I am willing my body to do.

I lie on my back with my hands folded across my stomach and visualise the cavity in my womb. A lumen, like the many others in the human body, but here inside my reproductive system, a space for life to grow. One by one I allow small points of light to appear, glowing softly in that darkness like candles lit at a vigil. Lumen, of light, from the Latin, lumen, an opening, from the same. I imagine doctors centuries ago, pulling apart bodies and peering into the tubes of the human system; assistants with tapers trying to illuminate secret structures to better understand their shapes and functions. Into the dark openings, bearing light, come the medical practitioners and the beginning of knowledge. Now we can go into the tiniest, most quiet spaces of the body and examine them. We have answers and methods, rescue attempts and exit strategies. The human body is a conquered land, and yet these centuries of knowledge might not help you. You can do everything they tell you to do, and still come out with nothing.

Illustration: Imogen Greenfield

It is not good to know too much. The internet groans with a billion imprints of lives and stories and dead babies and decaying eggs and missed chances and foods to increase fertility and advice on keeping your genitals cool and miracle conceptions and medical misadventures and commiserations about IVF. I can’t look away; eventually I find myself able to trace every living moment in my 28-day cycle, and repeat it perfectly. On any given day I could tell you exactly what my reproductive system is doing. I listen to my body the way you listen for a gas leak — with furious concentration, and fear. I imagine I can feel cells dividing and implantation occurring. Every ache in my abdomen might be a sign of life, every hearty food consumption might be a craving. It gets so bad that when my period arrives I am crushed and confused. The drawer of my bedside table is a graveyard for pregnancy tests. I no longer trust my own body. I wouldn’t know a real physical cue if it slapped me across the face.

What makes it worse is the missing out. The whole country cruises into summer. The days lengthen with warmth and cheer, and the collective sigh of five million skins sucking up vitamin D is audible across the land. But I’m unable to relax and not even really allowed to drink. I feel depressed, afraid of the two-odd weeks of waiting after the ovulation period. Uncertainty stretches on, endless, and into that space I project all my fears and all my hopes. I’m not a big drinker, but knowing I can’t or shouldn’t have a drink makes me rebellious, and it’s all I think about. I’m like an octopus prodded in a rock ledge — I come out, limbs flailing, a swirling mass of resentment and flashes of danger. I am dangerous.

Michelle Langstone is a North & South contributing writer. Her essay collection, Times Like These, will be published by Allen & Unwin in May.

This story appeared in the June 2021 issue of North & South.