The High Price of Absolutely Everything

Bullying, price gouging and market monopolies — the real reason New Zealand is so expensive.

By Ollie Neas

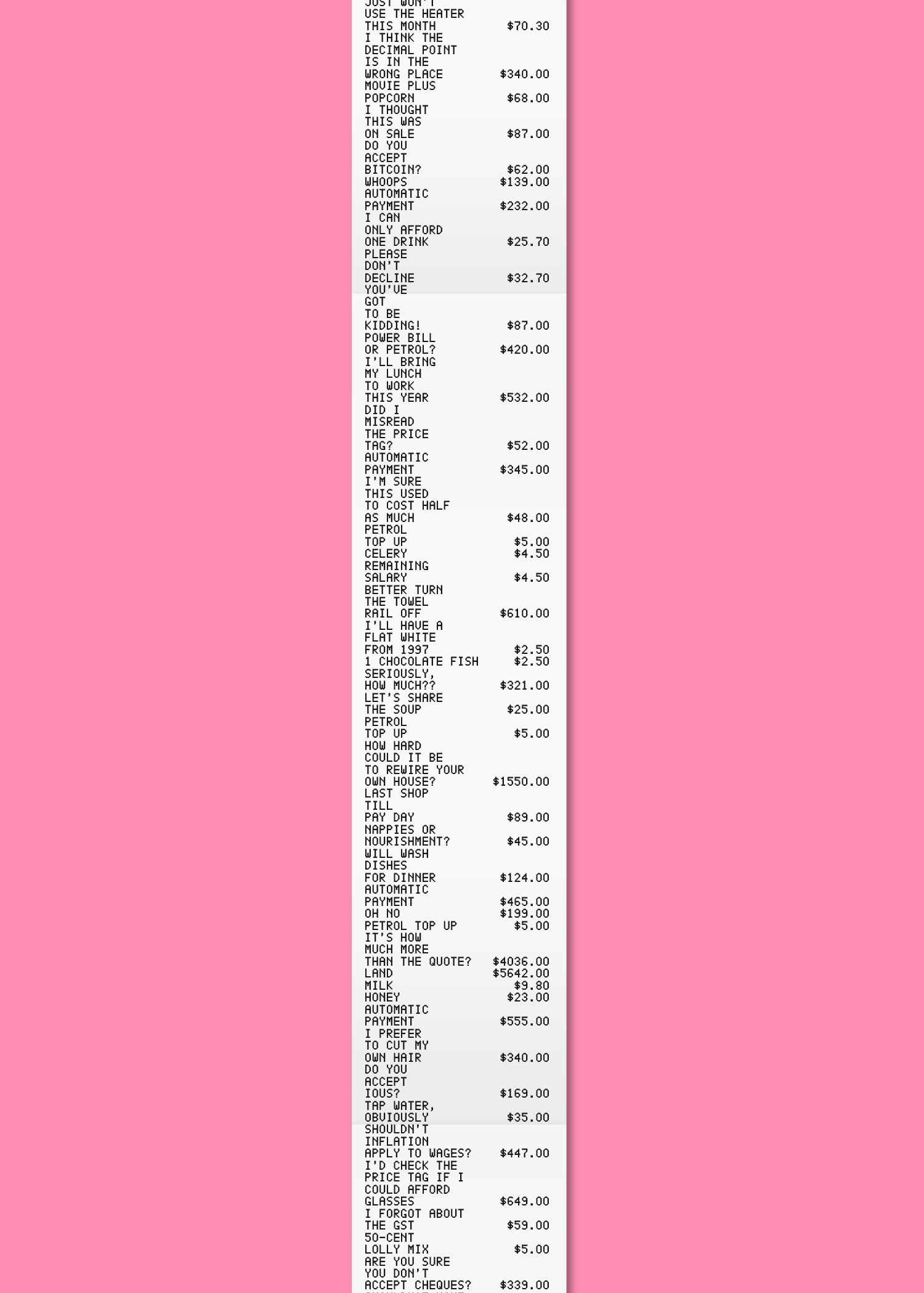

You are standing in line at the supermarket, asking the checkout operator if you can double-check the receipt. You are at home huddled next to the heater, staring confused at the power bill. You are calling your landlord to ask how your rent just went up by 20 per cent. All over the country, people are asking: Is it just me, or is life really bloody expensive?

For Louie, a biomedical engineer in his 20s, it was when he realised his rent had doubled in five years — even though his bedroom was windowless. For American expat Lisa, it was the grocery bill: she spends about twice as much on groceries here as in the US. And for Evelyn, a retired postie in Naenae, it was electricity. “I feel shocked — angry — when I see the power bill,” she told North & South. “They’re getting money for nothing!”

The usual explanation is that New Zealand is a small island nation in a distant corner of the world. It costs a lot to ship goods here. And our small population makes it hard for businesses to grow big enough for large-scale cost efficiencies. This is all true. But what if it’s not the whole story?

Four times a year, a horde of data collectors descends on the nation’s shops, checking the price of everything from software and staplers to peaches and Panadol. Their purpose is the consumer price index — the official measure of how expensive life is in New Zealand. The story these numbers tell is curiously deceptive. On the one hand, the prices of many things, from clothing to phones to flights, have fallen drastically in recent decades, as once-closed economies like China have been folded into the global economy. We can buy suspiciously cheap t-shirts. Technology that was previously in the realm of science fiction is within reach of those on modest incomes.

The price of the big essentials — food, shelter, power, transport — has jumped, increasing faster than inflation.

But at the same time, the price of the big essentials — food, shelter, power, transport — has jumped, increasing faster than inflation generally. Over the last 35 years, household electricity prices in New Zealand have doubled in real terms, rising faster than in other developed countries. Food prices have risen 55 per cent in the past two decades, even though we produce enough food to feed over 40 million people. We all know what’s happened to house prices. The average price of a home is now over eight times median household income, compared to two to three times income until the late 1980s. Rents have risen 1.5 times faster than wages over the last 20 years.

This affects everyone, but some of us more than others. If you’re on a lower income, you have to eat food and turn the lights on — those aren’t optional extras. This means that essentials eat up a larger portion of income for those who earn less. Over the past decade, lower income groups — like superannuation households, beneficiaries and Māori — have faced nearly double the inflation rates of high-income earners. And yet New Zealand as a whole is wealthier than ever before.

Since 2017, the government has launched a series of investigations into major sectors of the New Zealand economy — from fuel to supermarkets to construction to electricity. Some are complete; others are still underway. Together they offer something tantalising — the possibility of an answer to a long-standing question about life in New Zealand. In a time of such abundance, why is it so hard to get by? And does it need to be this way?

In late 2019, Foodstuffs North Island began rolling out new contracts for suppliers to its New World stores. The aim, the supermarket said, was to bring a new “customer driven” and “data driven” approach to procurement. But to the companies that actually make the products that fill supermarket shelves, it looked a little different.

If you run a food company, you’ll need to give the supermarket a cut of around 30 per cent just to get your product in the store (this varies from product to product and between supermarkets). You’ll also need to shell out a further 8 per cent or so to a merchandising agent to ensure your stock actually makes it to the shelf. This, it turns out, is not the supermarket’s job. To know how your product is performing, you’ll need to buy sales data off a third party the supermarket sells it to. And the risk is all on you — you’ll need to credit the supermarket for any unsold stock. It’s tough, but what’s your alternative?

The proposed new contracts gave the supermarkets even more leverage. Previously, suppliers dealt mainly with buyers from individual stores who had some autonomy over what to stock and what to promote or put on special. Under the new contracts, this would all be done centrally — and the supermarket would get a bigger cut. As one supplier described it, “we lose and our retail partner wins”. But the new contracts were voluntary. So some suppliers, preoccupied with a global pandemic, held off.

By May, as businesses emerged the other side of lockdown, it was becoming clear that the voluntary contract was not so voluntary. Suppliers reported coming under increasing pressure from Foodstuffs to sign on. Some were told that they wouldn’t be able to participate in promotions if they didn’t sign. Others who did sign found themselves needing to push the supermarket just to follow through with the promotions they were promised.

One company North & South spoke to found one of their most popular product ranges suddenly removed from stores. Head office had blocked it without warning. “We’d made all the stock in preparation for our normal orders, and then they weren’t coming in,” says a company representative, who has asked to stay anonymous for fear of repercussions.

Facing huge losses, the company put it to Foodstuffs directly: had they been blocked because they didn’t sign the new contract? Foodstuffs wouldn’t give a straight answer. “They’d be like, ‘Well, there’s a lot of factors we have to consider.’” The company wasn’t convinced. “They do this because they can. They are the more powerful player,” the representative says. “They’re like, ‘Well, where are you going to go? What are you going to do if you don’t have us?’” (Foodstuffs did not respond to questions.)

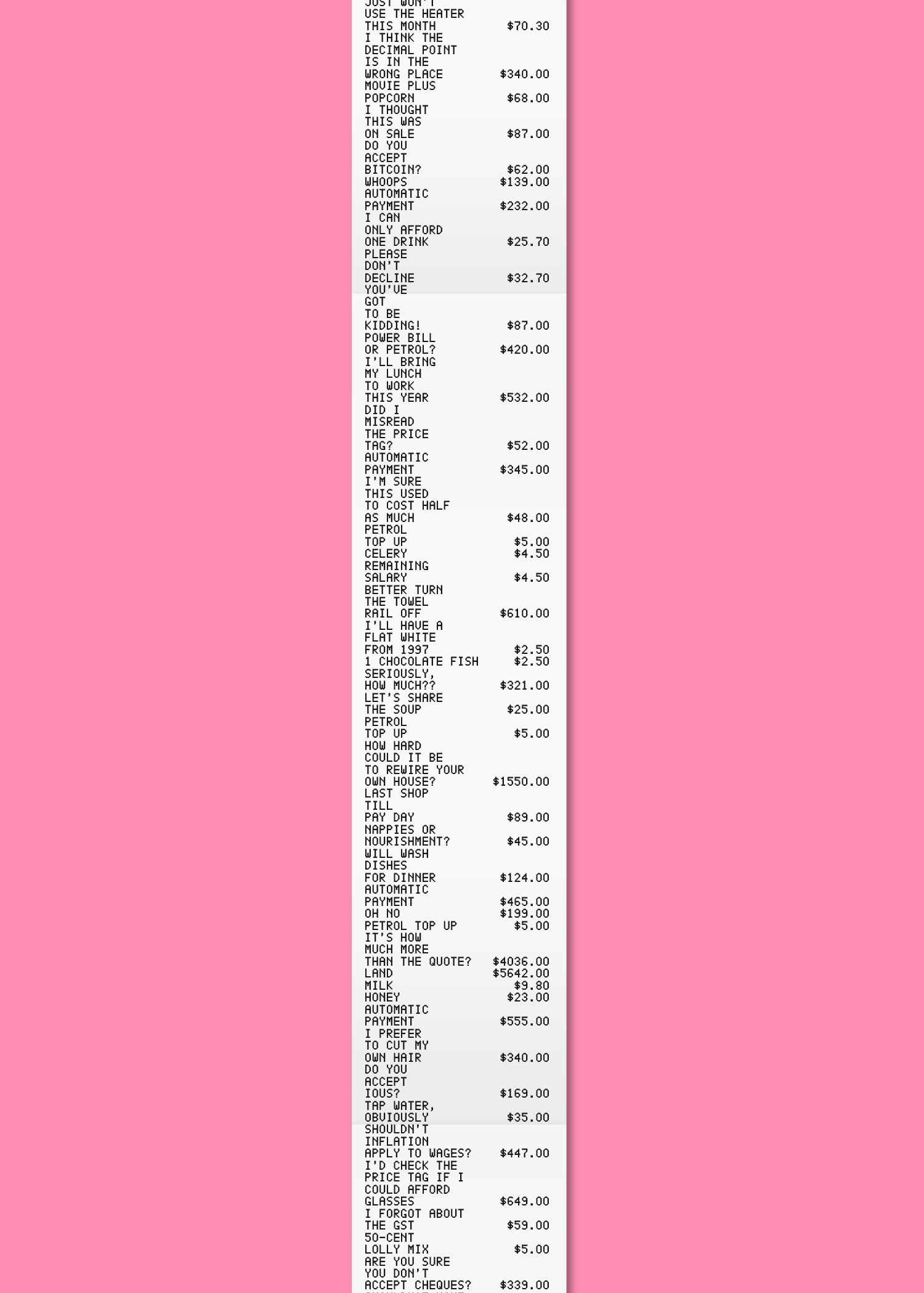

New Zealand’s supermarket industry is one of the most concentrated in the world. As a nation, we buy almost all of our groceries from just two businesses. There’s Foodstuffs, the New Zealand owned cooperative that runs New World, Pak’nSave, Four Square and On The Spot, among others. And there’s Australian-owned Woolworths, which owns Countdown, FreshChoice and SuperValue. By contrast, the largest supermarket chain in the United Kingdom makes up only a quarter of the market. There are concerns that our grocery duopoly is forcing suppliers out of business and keeping prices needlessly high.

Owning a single supermarket can make you a multi-millionaire.

The story behind the price of the items in your grocery basket — whether that’s a tub of ice cream or a bag of apples — is both incredibly complex and devilishly simple.

The vast bulk of the food we grow and farm is exported — 95 per cent of milk products and kiwifruit head abroad, for example (although only 32 per cent of vegetables, which are harder to ship.) That means that events overseas can have a big effect on the supply that’s available for domestic consumption. For example, an increase in people cooking at home around the world due to Covid-19 lockdowns has pushed up the price of New Zealand-made tasty cheese in local stores, as increasing demand is reflected in higher global dairy prices.

But those fluctuations aside, price ultimately boils down to an agreement between the supplier and the supermarket. That price needs to cover the supplier’s costs, some of which are unique to New Zealand. We pay more for biosecurity controls to keep the country free of the pests that could devastate our productive industries. Plus, there’s not many of us and we’re spread out across islands, pushing up distribution costs. Production will probably get more expensive as we adapt to climate change.

But on top of all that is the supermarket’s cut, which is generally understood to be around 30 per cent of the final price. Because most suppliers have to sell to them, the supermarkets have huge leverage to push the supplier’s cut down, helping keep their own profit fat. Because most customers have to buy from the two supermarkets, there’s very little competitive pressure. Why would Countdown drop the price of loo paper when it knows you’ll buy it from them no matter the cost?

On top of that, the supermarkets are often directly competing with suppliers through their own private brands — think “Macro”, “Free From”, or “Pams”. Foodstuffs even has its own fishing company. This kind of “vertical integration” is not always obvious to consumers, but puts independent suppliers at a distinct disadvantage when it comes to securing precious space on shelves.

Retail analysts believe that New Zealand’s supermarkets are among the most profitable in the developed world. Owning just a single store can make you a multi-millionaire. Some supermarket owners are worth over $50 million each. (The store with the most revenue is believed to be Pak’nSave Albany, with an annual turnover of between $150—200 million). As a whole, the industry takes in a staggering $22 billion annually.

Ever since the duopoly was born in 2002, with the merger of Progressive and Woolworths, supermarket profit margins have gradually increased. Last year alone, Woolworths’ net profits increased by over 11 per cent. In 2019, the Productivity Commission linked these high margins to “weakening competition over time”. Or, as Consumer NZ CEO Jon Duffy puts it, “there’s something funky going on” in the supermarket industry.

“Consumers are putting up with a facade of competition but actually there’s limited choice, high prices, crappy discounting behaviour, and commercialisation of customer data to wring even more profits out of your trip to the supermarket,” says Duffy. “All of these things wouldn’t necessarily be happening to the same extent in a competitive market.”

What’s missing is the hard proof, in part because the Commerce Commission — the body that enforces New Zealand’s competition laws — didn’t have the power to investigate the industry until recently. “We need someone to go in and say, ‘All right, you two supermarket giants, we want to look through your board papers and strategies to test whether you’re actually fat, dumb and happy and not really competing particularly hard’,” says Duffy.

Now, the Commerce Commission is finally attempting to do just that. In November 2020, the government announced a market study into the sector. From the commission’s office on The Terrace in Wellington, a team of seven investigators, analysts, lawyers and economists is analysing huge quantities of data from supermarkets and suppliers. When draft findings are released at the end of July, we could find out the answers to questions consumer advocates have been seeking for years.

Still, no one is suggesting that the government break up the supermarket duopoly, and the prospects of a new low-cost entrant disrupting the market seem slim. (The entrance of low-cost chain Aldi into the UK market forced the major supermarkets to drop their profit margins by more than half.) For one thing, there’s a lack of suitable land for potential competitors, due in part to existing players reportedly buying up the good land and sitting on it. The likely outcomes of the Commerce Commission study are decidedly less ambitious.

“We’re never going to get rid of the bloody duopoly. So how do we make that duopoly as economically efficient as possible? My answer is transparency,” says Mike Chapman, chief executive of Horticulture New Zealand. He suggests a code of practice that sets clear rules for supermarkets’ behaviour. This was one of the outcomes when Australia’s equivalent commission undertook a similar study in 2013. But given how squeezed some growers are at present, that may not automatically translate into lower prices for shoppers.

In the meantime, as the rollout of Foodstuffs’ new contracts continues, you might just find yourself wondering why your favourite product is suddenly missing from supermarket shelves.

In May this year, the government announced a major programme to boost housing supply. That same day, without warning, leading timber manufacturer Carter Holt Harvey stopped supplying to Mitre 10, Bunnings and ITM stores. Supply continued to just two stores: Carters, owned by Carter Holt Harvey, and PlaceMakers, owned by construction giant Fletcher Building. Suddenly, builders warned of price rises and construction delays as they scrambled to stockpile timber.

Carter Holt Harvey cited “short-term industry-wide supply issues”, while some blamed the mass export of logs to China, where our timber attracts a premium. But others saw more cynical motives at play. One industry commentator saw it as a “power move” to fight the low prices demanded of smaller retailers. ITM’s chief executive described it as a “corporate attack” that would “have ramifications for years to come”.

Regardless of the cause, it was an absurd problem for a country to be facing in the middle of a housing crisis. New Zealand is around 40,000 houses short, according to some estimates. But we are struggling to build houses. And when we do, they are expensive: the proportion of relatively affordable homes being built has fallen drastically over recent decades.

The causes of the housing crisis are incredibly complex. But building costs are undoubtedly part of the equation. The cost of building an average house has risen 180 per cent over the past 20 years — much faster than wages and consumer goods generally. It costs up to 25 per cent more to build homes here than in Australia, according to the Productivity Commission.

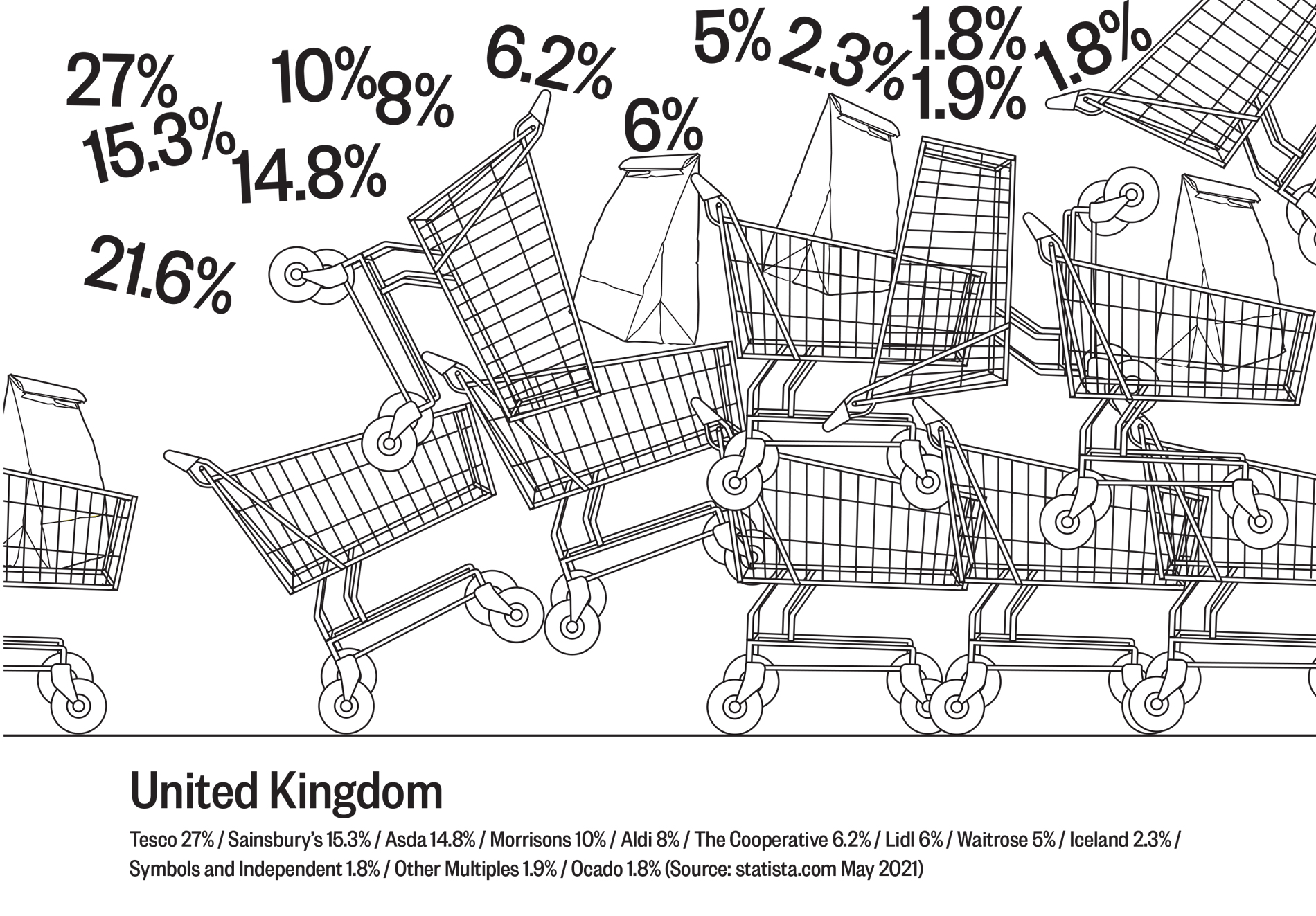

To build a house, you need land, infrastructure, builders. The cost of all of these has been rising. Then there’s the actual concrete, steel, timber, plasterboard, piping and paint that come together to make a house.As many as 45,000 different products may go into a house. On average, these materials are around 30 per cent more expensive here than Australia, on the Productivity Commission’s analysis. We pay “far too much for building supplies”, says Finance Minister Grant Robertson. After supermarkets, the Commerce Commission’s next target will be the building materials industry, with a market study expected to begin by the end of the year.

Building costs for an average house rose 180 per cent in 20 years — much faster than wages and consumer goods.

Explaining why building materials are so expensive isn’t easy. We build differently to Australians for one thing, which makes direct comparisons hard. New Zealand houses need to withstand earthquakes and we have a thing for bespoke homes. Only 1.4 per cent of Kiwi homebuyers select designs from a builder’s standard plans with no changes.

And then there’s the size problem again. “We have a population the size of Sydney spread out over around 200,000 square kilometres across multiple islands,” says John Tookey, a professor in construction management at AUT. “The physical cost of stocking and distributing materials, transportation, importation — this all makes the things you need to build buildings more expensive.”

But there’s something else unusual about New Zealand’s construction industry. While our builders are mostly sole traders or in small firms, just a few firms dominate the production and sale of the materials needed to build homes.

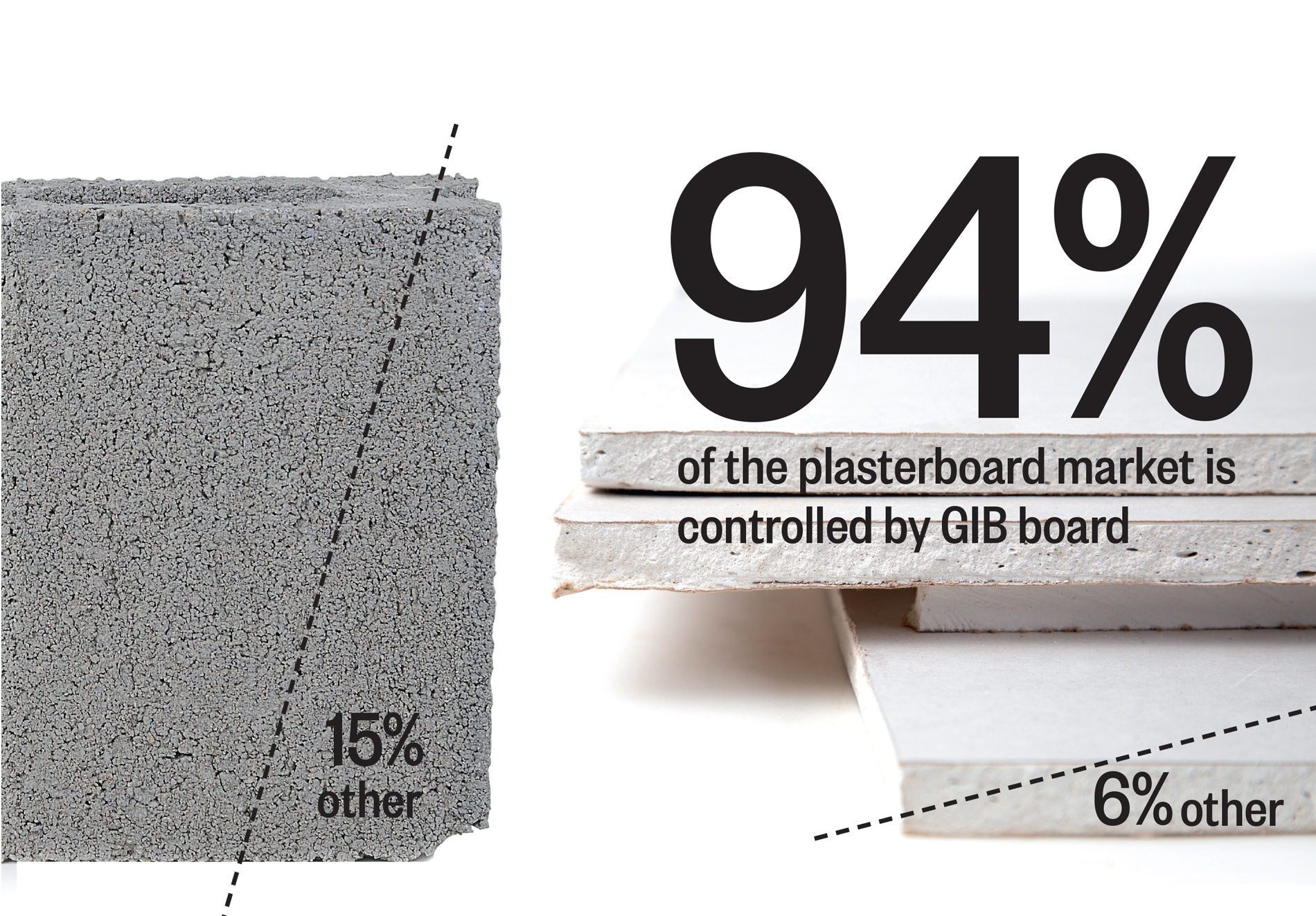

There’s Carter Holt Harvey, owned by New Zealand’s richest man. It controls nearly half of the country’s structural timber trade and sells product through its building merchant Carters. Then there’s Fletcher Building, the largest building materials supplier in Australasia, with a construction empire spanning 135 companies that generates over $7 billion in revenue annually. It is one of two firms that control 85 per cent of the nation’s concrete supply and one of three controlling 89 per cent of glass wool insulation supply. Its GIB board product has a staggering 94 per cent market share of the plasterboard market. It sells many of its product through its own stores, PlaceMakers and Mico. And many of its products end up in homes built by its subsidiaries, such as Fletcher Living.

The dominance of these firms is one reason cited by the government for the market study (although it didn’t actually cite the companies by name). As Council of Trade Unions economist Craig Renney puts it, the concern is that “the building materials market has been captured by one or two very large producers, and they can charge well in excess of elsewhere in the world for the same goods and services. That’s market failure.”

John Tookey of AUT says this concern amounts to little more than “a supposition” — that “because we only have a relatively small market, and we only have a couple of names in the market, therefore we’re being ripped off”. He argues that if profits really were “supernormal”, this would simply attract new entrants to the market, which would bring prices down.

But for that to be the case, competitors need to actually be able to enter the market. A string of Commerce Commission probes since the 1990s suggest the building materials companies may be throwing their weight around to prevent competition, through the use of predatory pricing to undercut competitors, and rebates and exclusive agreements to secure loyalty to their own products.

Despite these concerns, there has been only one hard finding of unlawful behaviour. In 2014 Carter Holt Harvey admitted to price-fixing for conspiring with a Fletchers subsidiary to sell timber at an agreed margin. On one view, this suggests the concerns about the construction sector are misplaced. There are rules and they aren’t being broken. But to others, this is just a sign that the rules are not fit for purpose.

In the early 2000s, the High Court and Court of Appeal found Carter Holt Harvey guilty of misusing its market power to undercut a competitor in the insulation market. And yet on appeal to the Privy Council in London, then New Zealand’s highest court, Carter Holt Harvey was cleared. The reason? It couldn’t be proven the company acted any differently than it would have acted were it not dominant.

This approach is highly unusual internationally. In most countries, courts focus on the effects of dominant businesses’ anti-competitive conduct. New Zealand is the only country that doesn’t do so, according to MBIE. As a result, the law fails “to condemn conduct that warrants prohibition”, as one US law professor put it. Right now, Parliament is considering introducing an “effects-test” for anti-competitive conduct, to bring New Zealand’s law in line with Australia’s. Backed by the government, the amendment is likely to pass, although an MBIE report notes opposition from “large firms and the law firms that represent them”. That change would likely mean the Carter Holt Harvey case would turn out differently if decided today.

For its part, Fletcher Building has come out firmly against the proposed market study into the building materials sector, with CEO Ross Taylor warning of a “climate of uncertainty for industry”. The firm points to a study it commissioned, which found the maximum contribution of Fletcher Building products to the cost of residential housing is only 13 per cent, excluding land and infrastructure costs, and suggests that overall construction costs may be closer to Australian levels than previously thought.

There is an irony in Fletchers facing this scrutiny. Eighty years ago it played a key role in solving an earlier housing crisis. Its founder James Fletcher was an enthusiastic advocate of public housing, and the company built much of the country’s state housing stock under the first Labour government in the 1930s and 40s. But times were different then. Faced with a depression and world war, the government needed the firm and the firm needed the government. Now, as house prices reach record highs, business is booming.

In November 2019, Phillip Anderson and his team of analysts at Haast Energy Trading noticed something odd. A huge storm had hit the country. A thousand foreign tourists were stranded by floods and landslides at Fox Glacier and Franz Josef. The Rangitata River in Timaru burst its banks. At the Waitaki hydro scheme, an hour’s drive inland from Oamaru, water levels were rising.

The one bright side should have been lower power bills. Hydro power is one of the country’s cheapest sources of energy — much cheaper than coal and gas plants, which need a constant supply of fuel. The massive rainfall should have caused prices to drop. Instead, that month, the wholesale price of electricity remained stubbornly high. Anderson thought he knew why.

His team had been monitoring the activity of Contact and Meridian, the two companies that dominate electricity generation in the South Island. As the rains fell, Anderson’s data showed Meridian was deliberately spilling water at their hydro dams, restricting the supply of hydro power to the North Island. To pick up the slack, gas and coal power stations in the North Island fired up. Due to industry technicalities, the power companies could then charge the higher price for the expensive coal and gas energy on all electricity — including the electricity produced at low-cost hydro dams.

Meridian claimed it was only spilling water for safety reasons given the heavy rains, as it is allowed to do. But Anderson believes they withheld generation to increase their profits. “In a competitive market, with water spilling from a dam, those hydro plants should be running at full capacity,” he says. On Anderson’s calculation, Meridian’s conduct cost energy users $80 million, while pumping 6000 tonnes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere unnecessarily. (Meridian disputes these figures.)

Anderson’s Haast Energy and a group of small retail companies took a complaint to the Electricity Authority. Following a six-month investigation, the authority found that an “undesirable trading situation” had occurred but declined to apportion blame, finding the incident to be the result of a “confluence of factors”.

To Anderson and the small retail companies, however, this was no isolated incident. “Meridian got away with it and made a truckload of money,” says Luke Blincoe, head of independent retailer Electric Kiwi.

We rely on electricity for almost everything these days. The experience of New Zealand households over the last 30 years has been of a steady creep upwards in power bills. Efforts to understand why are often confounded by the sheer complexity of the electricity market. But as the Meridian water spilling incident suggests, there may be a familiar story at the heart of it all.

New Zealand’s electricity market is dominated by five big “gentailers” — companies that act as both energy generators and retailers that sell electricity to customers. In theory, the host of small retail power companies should provide competition and help keep prices down. But small retailers buy their wholesale power from the gentailers — which are also their direct competitors in the retail market. And the gentailers have huge sway over the prices. “Meridian can almost singlehandedly decide what happens in the South Island. It controls about half of the hydro capacity and a lot of the storage,” says Anderson. He and Blincoe are calling for “structural change” to break up the big gentailers into smaller units.

There is a “very strong rationale” for the current arrangement, says economist Dr Richard Meade. The size of the gentailers helps keep retail prices steady. And combining generation and retail results in fewer players in the supply chain expecting a cut. In his view, there would also be little benefit to consumers from dividing up the gentailers further. The current system means “retail customers get a better offering and the firm makes more profit at the same time,” Meade says.

“We probably have the weakest electricity regulation in the world,” Stephen Poletti says.

The story of New Zealand’s electricity supply begins in 1888 on the West Coast, when Reefton became the first town in the Southern Hemisphere with a public electricity supply. Over the decades that followed successive governments took a keen interest in ensuring cheap power was available to all, linking the country up with a network of publicly controlled power stations and power lines.

The system was a “Rolls-Royce”, according to Dr Geoff Bertram of Victoria University’s Institute of Governance and Policy Studies, who has spent much of his career studying the sector. “It operated just about as well as it possibly could.” A single public agency — the New Zealand Electricity Department, or NZED — was responsible for generating the nation’s power and sending it to 61 locally owned electricity supply authorities, which then distributed it to households. Prices were set to cover costs, including investment in new infrastructure. For years, New Zealand had the fourth-lowest power prices in the OECD.

That all changed in 1987. As part of the fourth Labour government’s Rogernomics reforms, the government turned the NZED into the Electricity Corporation, a state-owned enterprise required to run on business lines. In the 1990s, responsibility for the national grid was split off into a separate company, Transpower. The Electricity Corporation was divided up into competing generators, which quickly bought up the retail companies, becoming the gentailers of today. Some were sold into private hands. Others remained as state-owned enterprises with mixed public-private ownership. A similar story happened with the old electricity supply authorities.

The logic was that costs would fall and those savings would be passed on to consumers. But the outcome, in Betram’s view, has been a “culture from top to bottom of profit taking and capital gains grabbing”.

“Once you deregulate and hand market power to corporate managers to maximise profit, there’s only one way things can go,” he says. “You’re left with only one question: Who’s the poor sucker who’s going to get their blood sucked out to finance this exercise? Big industry is able to look after itself, which leaves the residential consumers as the target.”

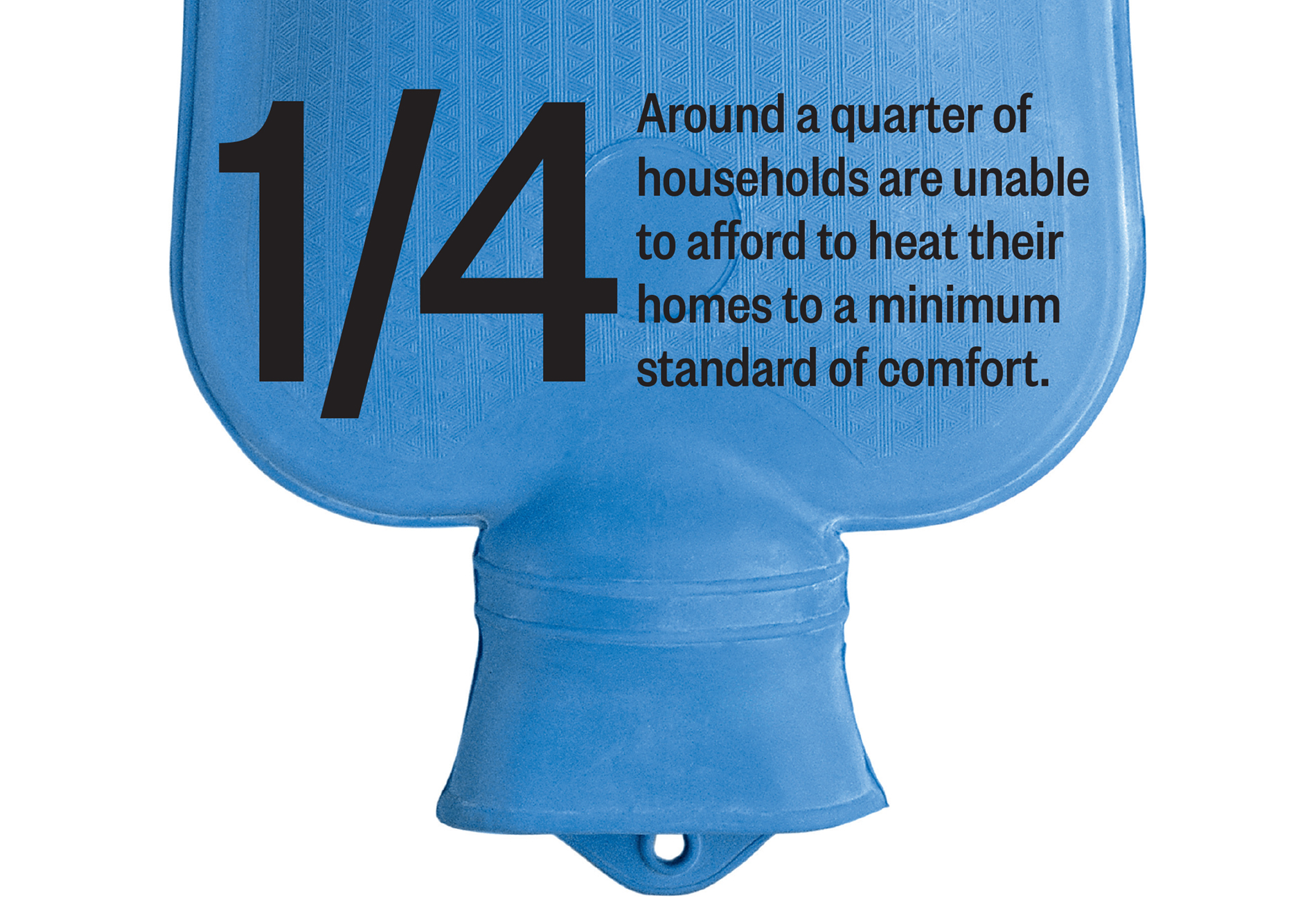

Since the reforms, the price of electricity supplied to residential consumers has doubled in real terms even as average prices across the OECD have fallen. Productivity in the sector has plummeted. And even as prices have gone up for residential customers, they have fallen for commercial and industrial customers — effectively shifting the burden of the electricity system onto Kiwi households. By 2015, around a quarter of households were unable to afford sufficient energy to heat their homes to a minimum standard of comfort.

“Much of the housing stock was built in the 20th century with cheap electricity available, so the low price of electricity was a major part of the New Zealand standard of living,” Bertram says. “As electricity prices have gone through the roof, there has been a huge squeeze on household budgets with a whole series of collateral effects. One of them is that people can’t afford to run their appliances. So they’re doing washing less, they’re cooking less, they’re turning off the water heater, and having fewer hot showers and hot baths.”

In 2018, the government commissioned a review of electricity prices and “energy poverty.” Despite proposing some tweaks to the retail market, it concluded that “wholesale prices appear reasonable compared to the cost of building new power stations”, and that grid and distribution companies were “not making excessive profits”.

To Dr Stephen Poletti of the University of Auckland, the price review was “a very weak report”. Despite its aims, he says the review “didn’t really say why prices have risen”. Using a different methodology, he found that the generation companies made $5.4 billion in additional profits between 2010 and 2016 over what they would have made if the market were truly competitive. These “excess profits” amounted to over a third of the companies’ revenue. It is a similar story with the distribution companies. Nearly half of what Wellingtonians (for example) pay for distribution costs goes to returns to investors. In the early 1990s, nearly all of that money went to operating costs and new investments instead. “We probably have the weakest electricity regulation in the world,” Poletti says.

Both Poletti and Betram would happily see New Zealand’s large generators returned to public ownership, with a fringe of smaller private players focused on innovations like rooftop solar. This is not the prevailing wisdom in the halls of power, as the findings of government’s electricity price review show. “Competition has definitely helped us at the wholesale price level,” says Meade. “Could we actually set up and run some other sort of industry that would deliver better results to consumers and wouldn’t cost more than it benefits? Under some alternative structure would we all be better off? I think the answer is plainly no.”

Is this, in other words, as good as it gets? This disagreement is about more than power prices. It is about a much deeper question — how to ensure the economy is fair and how to decide when the price really is too high.

In 2001, the chairman of Fletcher Building and Telecom penned an op-ed for an obscure journal answering a perennial question for New Zealand: In a small island economy, how do you let businesses grow large enough to succeed while maintaining competitiveness? His answer: let them grow, and rely on international competition to keep them honest. “Markets may not be perfect, but they do a hugely better job than bureaucrats,” the author wrote.

The op-ed was not particularly notable other than for the identity of its author, who appears curiously often in our story, although we have not yet mentioned him by name. Sir Roderick Deane may no longer be a household name, but he is one of the most influential people in New Zealand’s recent economic history. As deputy governor of the Reserve Bank in the late 1970s and early 80s, Deane developed a reputation for his intellect — and as a preferred scapegoat of then-Prime Minister Robert Muldoon. During the constitutional crisis of 1984, when Muldoon refused to devalue the currency despite the requests of the incoming Labour government, Deane was central in taking the unprecedented step of closing the currency to international trading to stem the flow of dollars leaving the country. But it was as a leading public servant during the fourth Labour government that he made his most lasting contribution.

Until the 1980s, a balance between big business and the little guy was struck by a state which actively intervened to regulate prices and provide essential services. Wages were set by the Arbitration Court at levels geared to improve living standards. Electricity was owned by the public and provided by the state. An army of publicly employed tradespeople built highways and houses at cost. Strong regulation made it unlawful to sell goods or services “at any price which is unreasonably high”. The system wasn’t perfect: high inflation and a lack of consumer choice were two obvious downsides. But for a time, there was security and the fruits of growth were shared relatively equitably.

By the 1980s, it was clear that something needed to change. Declining wool prices had undermined the country’s main money earner, and the economy was struggling to adapt under the government’s tightknit economic controls. One option was for the government to lead a gradual reorientation, preserving the basic balance between business, the unions and the state. But to a small circle of public-sector advisers — including Deane — the solution was a wholesale restructuring of the New Zealand economy.

Under New Zealand law, price-gouging is effectively permitted.

The second group won the argument. Previously protected industries were opened up to international competition. Wages were unmoored from prices. Price controls were unwound. The unions were weakened. Corporate tax rates were slashed. Many government agencies — such as the NZED — were sold into private ownership or required to operate as profit-making businesses. In a single week in April 1987, 5000 public sector workers were made redundant. Tens of thousands more redundancies followed. As head of the State Services Commission, Deane played a key role in the restructurings. The unions named him “Dr Death”.

With huge parts of the economy transferred to the private sector, and business freed from restrictions, government was faced with the basic question: How to prevent big business from abusing its power? Groups such as the Business Roundtable vigorously argued for minimal regulation, contending that competition alone would keep them in check.

The Commerce Act, passed into law in 1986, was supposed to be a middle ground between the old state-led approach and the neoliberal views of the Business Roundtable. Rather than focus on prices per se, the Commerce Commission would monitor the conditions of competition. Businesses with market power would be prohibited from using that power for anti-competitive purposes. Mergers would be prevented if they “substantially lessened competition” — except where the merger would “benefit” the public. The premise, says Richard Meade, was that “competition leads to good outcomes”. But the effect was a competition law that was — at least initially — significantly weaker than in most OECD countries.

Previously, businesses had been prohibited from charging “unreasonably high” prices. Under the 1986 law, prices are only regulated in rare cases (currently only electricity and telecommunications networks, gas pipelines, and airports). In all other cases, price-gouging is effectively permitted. And while mergers are only allowed if there is “benefit to the public”, regulators interpret the “public benefit” as being a matter of efficiency only. This allows mergers to proceed as long as efficiency increases overall, even if all the gains go to shareholders through high prices instead of to consumers.

Then there are the laws to reign in anti-competitive conduct, such as predatory pricing. As the Carter Holt Harvey case showed, businesses with market power are allowed to compete in almost exactly the same way as any other business — even if that undermines competition. In a recent article for Policy Quarterly, Geoff Bertram concluded that “no rational person would choose the regulatory arrangements that were established in New Zealand during the 1980s and 1990s.”

Having overseen the restructuring of the public sector, Deane entered business, leading many of the companies he had helped unleash from regulatory restraint. As CEO of Electricity Corporation, the state-owned enterprise that replaced the NZED, he oversaw the early deregulation of the electricity market. Under his tenure, the newly privatised Telecom became the country’s top performing public company as measured by investors’ wealth creation, following restructurings in which thousands of jobs were lost. In 2001, he presided over the break-up of Fletcher Challenge, then New Zealand’s largest conglomerate, selling off everything other than its building wing to foreign buyers. He would later have a hand in the supermarket trade, as board member of Woolworths Ltd, the Australian company that owns one half of New Zealand’s supermarket duopoly.

By the early 2000s, Deane was warning against what he saw as the creep of regulation back into business affairs. Government and business “both want growth for New Zealand and too often there appears to be conflict,” he told North & South in 2001. “Why can’t the country play the team game?” In 2000, as Telecom CEO, he reportedly lobbied the government to delay the introduction of a law change to restrict mergers.

In the years since, government has repeatedly tweaked the country’s competition rules. In 2018, the Commerce Commission was empowered to conduct market studies, allowing for the current supermarket and construction industry probes. There’s also that proposed bill to align New Zealand’s anti-competitive conduct rules with Australia’s.

The official view, according to Treasury advice in 2018, is that New Zealand’s competition law is “highly regarded internationally, but has some gaps”. Victoria University of Wellington’s Professor Lew Evans agrees. Following a long period of adjustment, “we’re pretty much getting it right”, he says. In his view, concerns about economic fairness are best addressed in other ways, such as through welfare policy.

But to Bertram, the debate about the rules of competition is about something much bigger. It is about the balance of power in a “small country where market power is exercised quite ruthlessly”. Ultimately, he says, “the weak and powerless need a champion”.

Milk and honey. Timber and steel. Pipes. Pies. A river of electrons running through a power line.

The big picture of the last 30 years is of two lines going in different directions. The line going down is the price of tradeable goods — those things that can easily be picked up and shipped around the world. The line going up the other way is for the price of everything else.

Faced with the pinch, it’s easy enough to forget the ways life has gotten cheaper. Overall, the purchasing power overall of even relatively poorer households has increased since the 1980s, despite a rise in inequality. Inflation generally remains low.

But why have the essentials become more expensive? One theory, among many, is that these are bottle-neck resources controlled by a few owners at a time when those who own things are becoming wealthier faster than those who work for their income. Another view is that we are reading patterns in the tealeaves — that there is no big picture here, other than the constantly shifting sum of humanity’s consumer choices.

The Commerce Commission’s market studies will provide long-awaited insights into how crucial areas of our economy really work. The first of these studies, into the retail fuel market, has already found that consumers are paying more for petrol than they should be. But these studies are, by design, limited. Their aim is to identify whether a market is as competitive as it should be. Some questions — and therefore some answers — are beyond their scope. What happens next ultimately comes down to a question that can’t be answered by economists alone: What is a fair price?

“The market price is just that — a market price,” says Craig Renney of the CTU. “It’s not the ‘fair’ price because generally speaking the market doesn’t really care about fairness. Fairness is in the eye of the beholder — be that the public or government or consumers.”

In the last 30 years, we have by and large treated the market price as the fair price. This is just the way it is, we say. Supply and demand. But when it comes to the essentials of life — housing, food, warmth — what if we said something different?

On a rainy Wellington Sunday, I walk down the aisles at Chaffers New World near Te Papa, among the crowds hurrying to finish the weekly shop. I’m confronted by a dazzling array of goods. The room is brightly lit and John Farnham blares from the speakers. As a corporate consumer, the supermarket will have benefitted from falling power prices while prices for you and me have increased. Just by sitting here on this plot of land, the value of which is rising by the day, the owner of the business is becoming wealthier and wealthier due to the same forces that have seen rents rise far faster than wages. It’s hard to keep all this in mind as I walk down the grocery aisle, just trying to keep count of the price of the items in my shopping trolley.

Ollie Neas is a contributing writer to North & South.

This story appeared in the August 2021 issue of North & South.