Culture Etc.

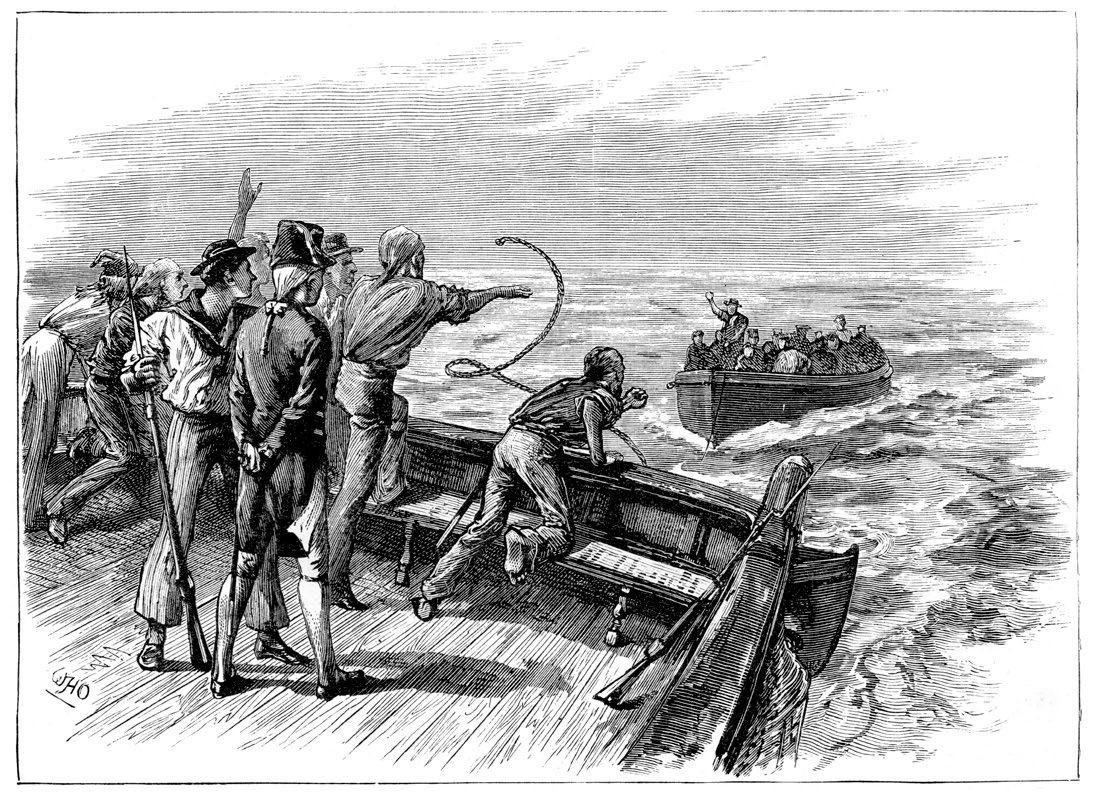

Above: Fletcher Christian and the mutineers set Lieutenant William Bligh and 18 others adrift, 1790 by Robert Dodd.

Bounty Hunting

After growing up with a family lore stranger than fiction, Harrison Christian finally sat down to try to untangle the story of his ancestor, Fletcher Christian, one of history’s most famous mutineers.

By Harrison Christian

In the late 1700s, a motley crew of European seamen and Polynesians sailed across the Pacific in a stolen Royal Navy ship. Their leader, Fletcher Christian, had rebelled against his commander, Lieutenant William Bligh, and cast him adrift in the Tongan islands. Now in control of Bligh’s ship, the Bounty, Christian and his followers were searching the South Seas for a hideout from the British navy. In the eyes of the law they were mutineers and pirates deserving of hanging.

The Bounty fugitives could not have found a better hiding place. They raised Pitcairn Island in January 1790, a high volcanic rock in the South Pacific. The island was uninhabited, but it had all the necessaries of life and, crucially, its location was unknown to Europeans. When Christian and his crew came ashore and founded their secret colony, Pitcairn became the most remote inhabited island on Earth. Fearing that the Bounty would advertise their presence, the mutineers set fire to the ship, stranding themselves forever.

Pitcairn was a salvation, but soon the island’s nascent colony fell into chaos. The men fought over the island’s limited resources, including the Polynesian women among them (viewed by some as sexual commodities). The Polynesian men, for their part, desired equal status to that of the Englishmen, and launched a rebellion of their own. By the time an American whaler stumbled across the island in 1808, only one of the mutineers was left alive: John Adams, the religious leader of a growing settlement of Bounty descendants. Fletcher Christian’s partner and children survived, but Christian was gone; Adams said he had been murdered.

Fearing that the Bounty would advertise their presence, the mutineers set fire to the ship, stranding themselves forever.

Fletcher Christian and his Tahitian partner, Mauatua, were my sixth-great grandparents. My fourth-great grandfather, Isaac Christian, migrated from Pitcairn Island to Norfolk Island on a British ship in the mid-1800s. Similarly remote, Norfolk Island is a tiny oasis between Australia and New Zealand where many descendants of the Bounty mutineers live to this day; a smaller number remain on Pitcairn.

My grandfather, John Garton Christian, was born on Norfolk Island and migrated to New Zealand under the shadow of World War II. He raised his family in the working-class suburb of Otahuhu, Auckland. He instilled his love of reading and his fascination with the Bounty story in my father. I’m sure it was the uncanny sense of possibility and destiny attached to the Christian name that helped drive my father from the freezing works in South Auckland to veterinary school in Palmerston North.

Like my father, I grew up steeped in our family’s Bounty lore. There was no shortage of material to feed my curiosity; Fletcher Christian had committed perhaps the most famous mutiny in history. Hundreds of books have been written on the mutiny of the Bounty, as well as Hollywood movies starring the likes of Marlon Brando and Anthony Hopkins containing varying degrees of fidelity to the historical facts. At school I took to writing, and by my early 20s I was working as a journalist. I always dreamed of writing a book, but frankly I didn’t think myself capable of doing so.

In early 2020, circumstances forced my hand. My wife and I were living in the United States when the pandemic hit. We went into a strict lockdown, and I lost my journalism job in Covid-related lay-offs.

Suddenly I had a lot of time on my hands, and I was only ever leaving our San Francisco apartment to walk the dog. I spent the next year writing a book about the mutiny on the Bounty.

Meanwhile, the political situation in the US was unravelling. The city’s shop windows were boarded up, the smoke from the California wildfires blotted out the sun, and President Donald Trump appeared to be rallying the nation to civil war. For much of this time, I was holed up in my bunker and poring through 18th-century documents. When I surfaced for air, I could look out at Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, and beyond, the open Pacific; the same ocean whose waters and islands I was navigating in my head. I decided that really understanding the mutiny on the Bounty required a before and after that was seldom given; it was a story which should be told as part of the human history of the Pacific Ocean.

Hundreds of books have been written on the mutiny of the Bounty, and Hollywood movies made containing varying degrees of fidelity to the historical facts.

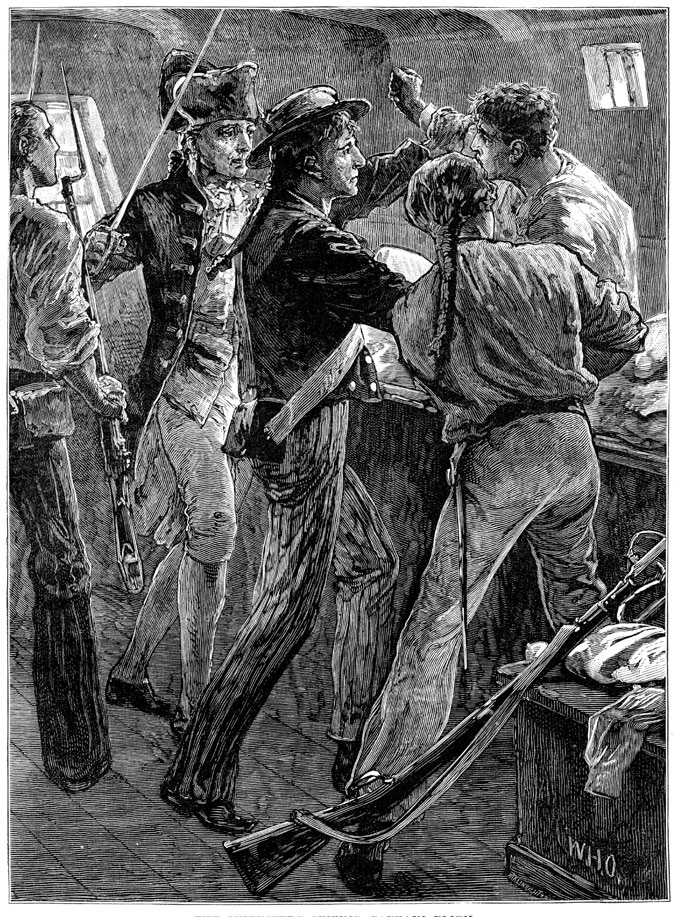

Mutineers seizing Captain Bligh.

I called the book Men Without Country, after a line in a Lord Byron poem about the mutineers. The statelessness and isolation of the Europeans and Polynesians on Pitcairn Island must have contributed to their darkest days. How did their colony survive for 20 years without any contact with the outside world? And how did the world react to the eventual discovery of the Pitcairn Islanders, by now a distinct, biracial people with their own language?

The research process was a cascade of new understandings about my family story and my own place in it. I found reams of primary sources online, including diaries, letters and court proceedings from the time. The Bounty crew members began to take shape in my mind’s eye, complete with tattoos and missing digits, which Bligh painstakingly recorded in his journal.

But the world of the Bounty is deceiving, full of unreliable narrators. William Bligh and his crew members all had some reason to bend the truth in their written accounts of the Bounty voyage. Fletcher Christian, for his part, left only his cursive signature among the documents; nothing he wrote down has survived. As the story progressed, I was forced to rely on the thinning circle of narrators around Christian. Ultimately, only John Adams remained as Pitcairn Island’s oral historian — and Adams was a man who never told the same story twice.

The ambiguity of the Bounty story and its characters has made them ripe for myth-making. Scholars still can’t agree on some of the key facts; for example, whether or not William Bligh was a bad commander, or why the mutiny occurred, or how Fletcher Christian died. Was Christian murdered on Pitcairn Island, or did he escape on a passing ship to his native England? Did Bligh abuse and humiliate his crew to the point that a mutiny could occur with little resistance, or was he the innocent target of a plot by his corrupt officers? Caroline Alexander’s 2003 book, Bounty, attempted to see Bligh as a profoundly misunderstood man, the victim of an elite conspiracy to smear his name after the mutiny. Alexander’s premise was not borne out by the evidence. It was the serving up of yet another Bounty myth, for another generation of readers.

Bligh cast adrift.

By the time I finished my book I felt a sense of responsibility, of setting the record straight on a story that had been played with for centuries. I also felt that the line to my ancestors was more tangible. It felt firm now, where before it had gone slack somewhere in the Pacific. Fletcher Christian and Mauatua I felt I knew better, but that isn’t to say I found all the answers. I still struggle to hold their figures in my mind. No portraits of them remain, and I’m not certain how they should appear to me from beyond the grave; whether they look hunted and afraid, or they’re smiling like the sphinx, the keepers of some riddle I have yet to solve.

Coming ashore on Pitcairn Island in 1790, Fletcher Christian was full of guilt and remorse about the mutiny on the Bounty, and hoped to live out his days in peaceful hiding. The abiding mystery of his character is owed to his success in carrying out that goal. At a time when the world was not yet fully illuminated in the European mind, Christian sailed purposefully into the darkness; and just as he planned, he has proven very difficult to find. Even for his own family.

Men Without Country is available in book stores from 7 July.

Harrison Christian is a writer from New Zealand living in San Francisco.

This story appeared in the August 2021 issue of North & South.