$1 Billion

And counting

Twenty years ago Peter Jackson brought Hollywood to Aotearoa — and we’re still shelling out mega bucks to keep it here. Is it worth it?

By Madeleine Chapman

Illustration: Dede Putra

They drank pinot noir and craft beer, and ate spaghetti alla chitarra at Amano in Auckland’s Britomart. The total bill was $1,428. They dined at Odette’s across town: $1,101.41. And they went to Waiheke for the day for $2,850. Amazon executives were here to discuss filming locations for their Untitled-but-clearly-Lord-of-the-Rings television series, and the New Zealand government was eager to make sure the trip left an impression. The hospitality was generous, noticeably more so than when some representatives from the New Zealand Film Commission stopped by Amazon Studios in Los Angeles in 2019 and were treated to an office lunch of “sandwiches and soda”.

For the past three years, the New Zealand government has pulled out all the stops to accommodate the biggest company in the world as it sought to make the most expensive television show in history. Convincing Amazon to film here required years of negotiations involving multiple government entities and closed-door meetings with ministers. One repeated sticking point was Amazon’s reluctance to guarantee that the show would be exclusively made in New Zealand. As negotiations dragged on, an initial plan to announce a deal on Frodo and Bilbo’s birthday — World Hobbit Day 2020 — did not come to pass.

In early 2021, it was finally declared that New Zealand would remain the home of Middle Earth for a show expected to last five seasons. The government would kick in the standard 20 per cent rebate on local spending for big international productions, plus a 5 per cent “uplift” for projects with “significant economic benefits”. In return, the government secured the rights to use the series as a branding tool for years to come.

By then, filming was already underway and shrouded in secrecy. The studios in Kumeu on the industrial outskirts of West Auckland were closed sets, with codenames for each location and scene. Huge water tanks were being used, but no one could say why. There were rumours of filming in Riverhead Forest and Muriwai, Queenstown and Fiordland. An urgent casting call was sent out in June 2020 for a show that the talent agency declined to name, seeking “funky looking people” with “long skinny limbs, deep cheekbones, lines on your face, scars, ears that stick out, bulbous or interesting noses”. One casting agent found great success in small town pubs, particularly the Puhoi Pub. Non-disclosure agreements were so strict that local actors couldn’t even reveal what accent they spoke in, let alone their character’s name.

The rewards, we were assured, were going to be huge: for film, of course, and tourism. But also technology, manufacturing, potentially even space. That was the rationale for the very steep price tag. If a location scout for Amazon flew from Auckland to Queenstown for $200, Amazon would get $50 back from the New Zealand government. A coffee bought by a production runner in Muriwai costs $4, and Amazon would get $1 back. The directors (all international) and stars (80 per cent international) worked here, so Amazon would be refunded 25 per cent of their salaries. The first season alone was estimated by economic development minister Stuart Nash to cost an eye-watering $650 million, which would have meant an equally teary contribution of around $162 million from the New Zealand taxpayer. Then, on 13 August, a few weeks after shooting on the first season wrapped, Amazon abruptly announced that it would be moving production to the United Kingdom. Some local crew were notified by email 20 minutes beforehand; others found out through media reports. Amazon said that it would no longer “actively pursue” the 5 per cent uplift, but it will still receive the 20 per cent rebate for what is expected to be the costliest season of the show by far: the huge first-season budget, an Amazon executive said, was “building the infrastructure of what will sustain the whole series”. Meanwhile, New Zealand lost what government officials saw as the key advantages of the deal: thousands of jobs and an exclusive lock on the Middle Earth brand. Even without the uplift, taxpayers are expected to funnel as much as $132 million to a company whose owner’s net worth rivals New Zealand’s GDP and who recently flung himself into space for fun.

Under the agreement between Amazon and the government, the company was required to give 12 months’ written notice to the New Zealand Film Commission of any decision to relocate the series. Stuart Nash, who was overseeing the deal, was informed of Amazon’s departure the night before the press release went out. There was no dinner.

“A film industry is about culture and money. It involves an endless tug of war between finance, investment and economic returns on the one hand and art, culture and national identity on the other.”

— New Zealand Film Commission, 1985 report

Twenty years after the release of The Fellowship of the Ring, the hobbits have finally left The Shire. When Peter Jackson built Middle Earth in Miramar, every Wellingtonian lived in it. Thousands auditioned to be extras and thousands more visited the Chocolate Fish Café in Shelly Bay, hoping to see a real-life celebrity in the flesh (and they did, all the time). Before a premiere for The Fellowship of the Ring in 2001, the capital, from the Beehive to the Embassy Theatre, quite literally shut down. When The Return of the King premiered, an estimated 100,000 people, every single one of whom presumably shared one degree of separation from the trilogy, attended the Wellington parade.

Jackson has had no official involvement with the Amazon series, but it would never have made its way to New Zealand without him. Having set up the studios, workshops, and soundstages for Lord of the Rings, he laid the foundation for creators with visions beyond the everyday.

You can see Jackson’s influence in the kinds of movies that have chosen to film here in the years since — massive budgets, elaborate visual effects, an abundance of green screen. The Last Samurai recreated Japan in . . . Taranaki. Flock Hill became Narnia for The Chronicles of Narnia trilogy, and New York was built in Miramar for Jackson’s King Kong. His personal relationship with James Cameron played a not-insignificant part in the US filmmaker buying a large estate in Wairarapa and deciding to film the Avatar sequels in New Zealand. And then, of course, there was The Hobbit, a very short book that Jackson turned into three very long films.

Some of these projects, like The Chronicles of Narnia and Mulan, spent millions filming in front of mountains and in rivers, allowing locals to yell “Oh that’s Cathedral Cove” when they watch the movies. Others, like Alita: Battle Angel and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes bear no visible trace of Aotearoa, having spent their millions on digital effects provided by the Weta Group.

But what ultimately lures mega studios like Amazon to our shores is one of the most generous film subsidy schemes in the world, which grew out of benefits originally provided to LOTR.

What is now known as the New Zealand Screen Production Grant refunds between 20 and 25 per cent of spending in-country on film production. This includes spending on any services provided in New Zealand, even if the person being paid (whether an actor, set producer, or director) is not a New Zealand resident. The largest local beneficiaries, by far, are Jackson’s companies, whose work on international productions resulted in $117.1 million being paid out of NZSPG between August 2015 and April 2018.

Meanwhile, the major American studios that contract Weta or that film in New Zealand have received nearly $1 billion since 2010. The scheme is currently paying out around $200 million annually, which means one in every $20 in New Zealand’s national budget is going to international productions. The scheme is also uncapped, which Treasury has flagged as a “significant fiscal risk”, especially as behemoths like the Avatar sequels gather momentum. Amazon may have taken the subsidy and run, but others will likely take its place.

Twenty years ago, Sir Peter Jackson single-handedly brought Hollywood to Aotearoa. And ever since, he’s exerted his influence to keep it here, no matter the cost. He’s led the transformation of New Zealand’s film industry from a small, domestic government-subsidised industry to a massive, international, government-subsidised industry. In the wake of Amazon’s hasty departure, it’s worth asking: Is this actually good for the New Zealand film industry — or for New Zealand?

Peter Jackson is typing up a long, angry letter. He’s in his 20s, living with his parents in Pukerua Bay, and is filming his debut feature Bad Taste on the weekends with his friends. He started working on the movie in 1983, when he was 22. It was originally conceived as a short film with a car chase and a bit of cannibalism. After filming sporadically for a year, Jackson put together a rough cut and his “short film” came out at 50 minutes. Instead of editing it down, he and his friends decided to make a full-length splatter film.

Jackson wrote the script, directed, made props in his parents’ kitchen, designed special effects, and acted in multiple roles. By the time Bad Taste premiered in 1987, Jackson had proven himself to be a single-minded genius behind the camera.

His early career showcased what’s possible when creativity meets a lack of resources. Right from the start, he pushed relentlessly to overcome the constraints of budgets and time. In 1978, as 16-year-olds, Jackson and a bunch of friends from Kāpiti College entered an amateur film-making competition. Their film, The Valley, featured a violent fight to the death between man and cyclops. Every other film in the competition was a maximum of three minutes, while The Valley ran for 20 minutes. It didn’t win.

But back to the letter. After deciding to turn Bad Taste into a feature, Jackson sought funding from the New Zealand Film Commission, established in 1978 to support the country’s tiny film industry. When his application was declined, the 23-year-old fired off an eight-page typed screed which he later described as “exacting my anger on the Film Commission for turning me down”. Further correspondence followed and eventually his persistence paid off. The film commission became a major funder for Bad Taste as well as Jackson’s next four projects: Meet the Feebles, (a dark satire with puppets); Braindead (a zombie comedy), Heavenly Creatures (an Oscar-nominated dramatisation of a 1954 murder in Christchurch) and Forgotten Silver (a mockumentary about a fictional New Zealand filmmaker).

Danny Mulheron, Jackson’s co-writer on Meet The Feebles, summarises Jackson’s general attitude as “What’s good for Peter is good for everyone”. Describing Jackson’s style as a director and as a person, Mulheron equates him to a tortoise. “He’s very pedantic and slow and deliberate in everything he does,” Mulheron says. “He’s got an exceptional ability and a single-mindedness. He’s never taken his eye off what he wanted to do and that’s why he’s way more successful than possibly anyone else.

“That’s his superpower.”

When plans for Jackson to direct a King Kong remake fell through in 1997, he set his sights on Lord of the Rings. Initially plotted to be a single epic film, it quickly became two, with the treatment — not the script, the treatment — clocking in at 92 pages. With Harvey and Bob Weinstein attached as producers, Jackson and writing (and life) partner Fran Walsh convinced them to bankroll two movies. But it soon became apparent that the budget of $75 million wasn’t nearly enough for what Jackson and Walsh had conceived. After staring down Harvey Weinstein — one of the most powerful people in Hollywood at the time — Jackson found a new funder in New Line, and one movie became three. The trilogy wound up costing $281 million to make, and brought in just under $3 billion at the box office.

According to a 2007 cabinet paper, “the Inland Revenue Department estimated the Lord of the Rings films alone cost the government between $300–400 million.”

Even as Jackson became a power player in Hollywood, he couldn’t seem to leave the Tolkien universe behind. He kept hoards of props from filming and wrote 20-page responses to fan questions. In 2006, it was revealed that Jackson was doing extensive renovations on his sprawling Wairarapa estate to include an underground functional replica of Bag End, Bilbo Baggins’s home. Three years later, Jackson signed on to direct The Hobbit, which was initially conceived as a two-movie project but, true to form, became a trilogy.

A few months before the final Hobbit movie was released in 2014, celebrated director Geoff Murphy (Goodbye Pork Pie, Utu) received an honourary doctorate from Massey University. Murphy, who worked with Jackson on The Lord of the Rings, dedicated a large portion of his speech to his fellow director. “For a few golden years there we gave the country its own heroes and they loved it. However it wasn’t to last because this other fellow turned up. A fellow called Peter Jackson,” said Murphy to a packed theatre of graduates. “And he stole the film industry off us . . . he became flavour of the month in Hollywood. And he has stayed flavour of the month in Hollywood for something like 14 years, which is an extraordinarily difficult act.”

“Peter doesn’t make New Zealand films, he makes films for Warner Brothers. He makes commercial product for the international market. The films he makes have got very little to do with us culturally. But it won’t last forever. And then perhaps he might come back to New Zealand and start making New Zealand films again. That’d be good.”

That same year, Jackson remarked that he and his partner Fran Walsh hoped to “tackle some New Zealand stories . . . certainly that’s where our hearts are, to go back into that world of slightly more low-budget, Kiwi stories.”

In May 2020, with New Zealand’s border closed to all foreign citizens, only essential workers were allowed to operate outside their homes and only the most essential were granted admittance without a New Zealand passport or residency. That month, 56 film workers from the United States flew in on a chartered plane. Among them were James Cameron and his crew, to continue the apparently vital task of filming Avatar 2. They were categorised as “other essential workers” on the grounds that they provided “significant economic benefits”. The decision, signed off by then- Minister for Economic Development Phil Twyford, angered many whose loved ones and employees had been denied re-entry for months. And it highlighted, perhaps for the first time to many, the extent to which New Zealand has tied its identity and economy to the international film sector.

There was no subsidy scheme when the original LOTR trilogy was made. But it benefited from a significant tax loophole for production companies filming in New Zealand. In 1999, the National government looked to close the loophole, but an internal email from IRD to Treasury suggested one exemption: “the political risks, especially in relation to the Lord of the Rings, should be highlighted”. Jackson’s trilogy became the last project to benefit from the loophole. A 2007 cabinet paper from the office of the Minister for Economic Development states: “It is difficult to definitively quantify how much this loophole cost the government’s tax base but the Inland Revenue Department estimated the ‘Lord of Rings’ films alone cost the government between $300–400 million.” The entire budget for the trilogy has been reported as being anywhere from $270–$675 million.

Looking back, it’s often assumed that the film subsidies system was an attempt to capitalise on LOTR’s success. In fact, the opposite is true. The same 2007 cabinet paper notes: “A key motivation for introducing the [subsidies] was limiting government expenditure on film activity.” The paper goes on to state that had the subsidies been in place instead of the tax loophole, government assistance would have been closer to $50–60 million.

The scheme began as the Large Budget Screen Production Grant in 2004, shortly after the release of The Return of the King. It allocated up to $40 million per year in 12.5 per cent rebates for international productions that spent over $15 million here.

New Zealand could spend between $200–250 million on the Avatar sequels. This is more than the government’s entire 2020 budget allocation for transitional housing ($150 million).

At the end of 2013, Jackson attended an event at parliament where it was announced that the baseline rebate would increase to 20 per cent, with the opportunity for major projects to apply for a 5 per cent uplift. The very same day, a second announcement was made: James Cameron would make his Avatar sequels in New Zealand and receive the new 25 per cent rebate. Cameron was present alongside Jackson at the announcement of the new scheme, now named the New Zealand Screen Production Grant. Since 2017, the scheme’s baseline funding has been approximately $50 million a year — meaning any additional spending needs to be reallocated from other areas of the budget.

The Avatar sequels, for instance, have so far received $119 million. (In case you’ve lost track, Avatar 2 is scheduled to be released in December 2022, with three more following in 2024, 2026 and 2028.) It’s estimated the science-fiction series about humans colonising new land for metals until a white man falls in love with an indigenous woman (think Pocahontas but — well, just Pocahontas) will end up costing over $1 billion, with NZSPG subsidising between $200–250 million of that. If the trilogy goes over budget, NZSPG will continue to pay out 25 cents for every dollar spent. Even sticking to the budget, this is more than the government’s entire 2020 budget allocation for transitional housing ($150 million).

NZSPG also pays out tens of millions of dollars in post-production grants a year to overseas studios, at the same rate of 20 per cent on every dollar spent on services within New Zealand. Most contract Weta Digital to do special effects work on blockbusters like Alita: Battle Angel (which received $25 million), War for the Planet of the Apes ($26 million), and Alvin & The Chipmunks 4 ($12 million).

“Once you’re into the game of film subsidies you have to be in it — the rest of the world is in it and if you want a film industry this is part of the price you pay.” So said finance minister Grant Robertson when asked to justify the ongoing expenditure earlier this year. And New Zealand isn’t just in it, we’re leading it. Ireland’s standard subsidy is 32 per cent, but it caps spending at €70 million ($117 million) per project. Many European countries offer between 25 and 33 per cent but almost all have a cap. Australia has no cap but a lower rebate of 16.5 per cent. The UK offers 25 per cent, but only for 80 per cent of expenditure. With the various caveats, no single project is likely to receive anything close to $162 million.

And the benefits for international studios aren’t limited to just the subsidies. A typical production budget includes money for “fringe” costs, which are additional obligations that crew or actors’ unions may require for benefits like holiday pay or health insurance. Almost every major country in the world requires fringes except New Zealand. Even on projects like Avatar that can span up to seven years, all New Zealand crew are just contractors. “It’s like hiring a camera,” says producer Desray Armstrong, who has worked on both local and international productions.

The reason dates back to a public stoush in 2010 — and at the centre of it all, writing letters and requesting meetings, was Sir Peter Jackson.

Jackson has been nicknamed the “King of Miramar” due to his overwhelming presence in the Wellington suburb. Large plots of Miramar land and businesses were bought by Jackson, Weta Workshop’s Richard Taylor, and various investors to accommodate film studios and workshops during filming of LOTR. He owns large share packets (often a full or majority share alongside Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens) in the following companies: WingNut Films (production), Weta Digital (visual effects), Weta Workshop (special effects and props), Park Road Post (post production), Portsmouth Rentals (film equipment rental) and Camperdown Studios (film studios). There are few services in the making of a film that can’t be undertaken by a Jackson-owned company.

When LOTR became a global phenomenon, the barefooted Jackson became a local hero. His apparent lack of interest in Hollywood and its glamour only magnified his public image as an affable nerd who just wants to make cool movies. In a sense, Jackson is still that nerd wanting to make cool movies, but in two decades he has accumulated a lot of power and isn’t shy about using it.

“He’s not a political character and that makes him a political character,” says Mulheron. “He’s only interested in what he’s interested in and he’s blind to everything else.”

New Zealand got its first glimpse of Peter Jackson, the political character, with the infamous episode now colloquially known as The Hobbit Law. Before production began in 2010, The Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) in Australia, acting on behalf of New Zealand Actors Equity, requested a meeting with Warner Bros. Unlike overseas union actors on the LOTR movies, New Zealand actors received no share of the residuals from the sale of DVDs and merchandise. MEAA also raised issues with unpaid delay periods and health and safety. After Warner Bros refused to negotiate, unionised actors around the world agreed to a “do not sign” order on their contracts until New Zealand actors were able to discuss their own.

Two days later, Jackson sent out a long, angry letter as a press release. The writing was emotional. He called the “do not sign” order a “power grab” from “an Australian bully-boy, using what he perceives as his weak Kiwi cousins to gain a foothold in this country’s film industry”. He warned that if The Hobbit were filmed elsewhere (the first time the notion was floated publicly), “look forward to a long dry big budget movie drought in this country”.

Over the next four weeks, what had started as a request for a meeting became a national emergency, culminating in 1500 film workers marching through the streets of Wellington, pleading with Warner Bros to keep The Hobbit in New Zealand. Jackson, Walsh, and Boyens warned that as a result of the actors “boycotting”, Warner Bros would most likely move the production overseas.

“A lot of actors were very frightened,” says Ward- Lealand, president of Actors Equity in 2010 and its spokesperson during the subsequent fallout. “We were seen as the bad people in the industry who were going to remove millions of dollars from New Zealand.”

At the time, local filmmaker Roseanne Liang wondered if little New Zealand was in over its head. “You see actors and crew people fighting and crying at each other across a community hall and you are like, how did this happen?” she recalls. “At what point did the money become more important than people’s health and welfare and livelihoods?”

In a television interview, Jackson quashed any suggestions that Warner Bros might in fact be the “bully boys” in the situation. “They don’t want extra subsidies,” he said. “All this conspiracy theory nonsense about them wanting more money and more subsidies, no.”

The following week, Warner Bros got more money and more subsidies. Their executives flew into Wellington, were chauffeured in government limousines and hosted at Prime Minister John Key’s private residence. They left the negotiations with an extra $20 million tax break on top of their standard 15 per cent rebate plus $10 million for marketing costs and an extraordinary amendment to New Zealand’s employment law passed in Parliament under urgency.

Previously, all employees in New Zealand had the freedom to choose whether or not to belong to a union and bargain collectively — and employers are not allowed to discriminate based on a person’s union membership. Until 2010, the only exception to this law was volunteers. Following negotiations between Warner Bros and the Key government, two more exceptions were added:

(i) a person engaged in film production work as an actor, voice-over actor, stand-in, body double, stunt performer, extra, singer, musician, dancer, or entertainer:

(ii) a person engaged in film production work in any other capacity.

This is a significant saving for movie studios. Fringes can cost anything up to 20 per cent of wages for union members across cast and crew. With thousands of contractors, fringe costs add up. By ruthlessly eliminating these potential costs for international productions, New Zealand has set itself up as an attractive film location in more than just the literal sense.

Ken Hammon, the star of Bad Taste, told the New Zealand Herald in 2012, “Pete does have this kind of nice guy image and it is not entirely earned. He is a ruthless businessman.” That same year, then-Prime Minister John Key told The New York Times, “Peter is a very, very big fish in quite a small tank.”

“You have blockbuster producers like Peter Jackson all over the world who become a bit influential and then they throw their influence around,” says Gemma Gracewood, who worked for the Labour government in the early 2000s when the first film funds were being developed. “That’s not unique to New Zealand. It’s just that we really only have one of them.”

Then-Prime Minister John Key and Sir Peter Jackson at Hobbiton in 2012. Photo: Stuff Ltd.

Picture this: it’s Christmas 2023. One of the two gifts you unwrap is a DVD copy of the latest Avatar film. You thank the giver and wonder if you know anyone with a DVD player. You can’t remember the last time you bought or even watched a DVD. “It’s the special features edition,” says your uncle, speaking from the year 2004. You turn the DVD over and see that he’s right. The DVD includes a featurette on filming Avatar in New Zealand, proudly brought to you by the New Zealand Screen Production Grant (NZSPG). You make a note to keep an eye out for vintage players at the next garage sale you see and put the DVD on the shelf next to a box set of The Sopranos.

The memorandum of understanding signed between James Cameron, his production company Lightstorm Entertainment and the New Zealand government in 2013 for the 5 per cent uplift is worryingly slim at just six pages, including the cover page and the signing page. In return for what is expected to be a $50 million payment for the uplift, Cameron and his team were required to produce 10 deliverables. One is a logo in the credits “acknowledging the support and co-operation of the Crown” and another is “a chapter on filming in, and other aspects of, New Zealand on DVDs and Blu-rays” — but only if there are special features included on the DVD. Current trends suggest the economic benefits of a special featurette on a DVD in 2023, when the first Avatar sequel is expected to be in stores, will be minimal.

Deliverables from other MOU signed with major film studios have been equally middling. The Amazon MOU, for instance, included the requirement that a New Zealand Film Commission representative be escorted down the red carpet at the show’s premiere. The film commission confirmed that Amazon had “not met all of the notice requirements outlined in the MoU. New Zealand partners are continuing to work with Amazon Studios on conditions of the termination.”

In order to prove that they’re helping to grow New Zealand’s film industry, productions receiving the 5 per cent uplift are required to pass on knowledge in some way, such as through an internship programme on set or a mentor system. The Mulan MOU, for instance, resulted in the 2019 Power of Inclusion summit in Auckland, hosted by the film commission and “supported by Disney Studios”. The summit, pitched as a two-day conference “presenting views from diverse global communities and positing future action to create a more inclusive industry and world” drew criticism for the cost of tickets ($495) which priced out many people the summit was supposed to assist. Despite high-profile speakers like Geena Davis, the general review of the event was that it featured more platitudes than substance.

Roseanne Liang was a direct beneficiary of an MOU a few years ago, working as an intern on an American TV show, one of three interns across writing, directing, and stunts. “We were just something they had to do to access some money so they kind of did as little as they needed to do with us and then we were stuck in a corner,” she remembers. “I definitely learned something . . . [but] there is an element of lip service.”

These extra benefits are what Gracewood calls “film diplomacy” — initiatives to bolster the perception that there are countless benefits to spending huge sums of public money on these productions.

“When you’re the ministers on the arts and broadcasting side of the fence and you’re sitting at the cabinet table with all of your colleagues who are saying ‘Housing, health, education, sport, tourism, business’ you need to bring more than just ‘It’s gonna be good for us’,” says Gracewood.

“The arts doesn’t really win votes,” she continues. “But when you can say there are economic benefits and there’ll be stars walking around in our midst, pissing in the bucket fountain and eating our great restaurant food, we get excited about it.”

Oscar-nominated producer Chelsea Winstanley says paying crew for local work compared to Avatar and Lord of the Rings is “basically asking them to work for a box of beers”.

Film subsidies have been enthusiastically championed across the political aisle since they began. When the National government increased the subsidy rate, then-economic development minister Steven Joyce said the Avatar films would “be a very big boost to the screen industry while we look to develop more New Zealand-sourced productions”.

Back in May, when Amazon was still filming in New Zealand, Stuart Nash described himself as “a huge fan” of the deal. For “a number of reasons”, he explained — chief among them the economic boost it would provide. The production was touted as having cast New Zealand actors in over 60 per cent of speaking roles and 20 per cent of the core cast, with local practitioners making up almost 95 per cent of the crew. Big spending within New Zealand is the first point of defence against the collective gasp that might be provoked by a subsidy of up to $162 million. Yes, we are paying, but we’re getting three times that amount pumped into the economy, says Nash, so it’s a net economic benefit.

The true economic benefits, however, have proven virtually impossible to measure. An evaluation of NZSPG by the Sapere Research Group in 2018 concluded that for every dollar spent on international film grants, New Zealand received $2.35 in net benefit. (The report also noted that “the industry does not appear to be sustainable without the grant”.)

Subsequently, two independent reviews of the Sapere evaluation, commissioned by MBIE, questioned the validity of its numbers and suggested that the direct economic benefits for New Zealand were likely to be minimal, possibly even a cost.

In 2018, then-Minister of Economic Development David Parker teased a possible restructuring, perhaps a cap on the subsidies. Shortly afterwards, Jackson requested a meeting with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Parker at parliament. Three weeks later, it was announced that no cuts to the scheme would be made.

Jackson rarely, if ever, grants interviews to local media. He and his team didn’t respond to multiple requests for interviews for this article. Instead, he writes letters and statements and posts them to his Facebook page. In 2018, he sent a lengthy defence of the subsidies to the New Zealand Herald’s Matt Nippert, emphasising that bringing international films to New Zealand has never been about money. “This is not a debate about whether government incentives are a good or bad thing — if no other countries provided incentives to their film industries we’d be on a level playing field,” he wrote.

“In my mind it’s very simple: Does New Zealand want to have a film industry?”

It’s a cleverly posed question from a man who’s won many, many arguments in his life. And of course the answer is yes. But what kind of film industry?

Films like Whale Rider, Boy, and Goodbye Pork Pie are the platonic ideal of New Zealand film. Stories about New Zealanders, told by New Zealanders, for everyone. But those films are sadly rare. Only 16 locally funded films have turned a profit in New Zealand. Ever. That is the New Zealand film industry.

The two industries that exist alongside it are international films that happen to be filmed here, like Pete’s Dragon, which was technically made by hundreds of New Zealanders and featured local actors in minor roles, but whose sensibility is decidedly global. And films made by New Zealanders overseas that are very much of this place, like Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarok starring local favourite Rachel House as a surly bodyguard with a distinctly Maori sense of humour.

When the NZSPG was announced in 2013, with the increase of the subsidy and the new uplift, the argument was that the influx of international productions would also benefit our homegrown industry. “These changes will enable larger scale New Zealand productions to be made as well as encouraging more New Zealand stories to be seen on screen,” said the then chair of the New Zealand Film Commission, Patsy Reddy.

Thanks to the NZSPG’s requirement that overseas productions use majority local crew and that a portion of onscreen talent be New Zealanders, approximately 15,000 people are employed (but not as employees) across the screen sector. There are New Zealanders who began their careers on Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit who now work as stunt people, makeup artists, and producers on major international features. New Zealanders have won Oscars, BAFTAs and everything in between. Projects like Avatar and Lord of the Rings keep their skills in the country, at least for a while.

“When you’re looking at tax going to international productions it’s like ‘why the fuck are we paying all this money to these guys when our education system is at times woeful’,” says Desray Armstrong, who has crewed on big budget international films and is now producing her own projects. “But I guess looking at it from within the industry . . . they’re coming here, we’re working, we can take those skillsets onto our own productions and the international relationships gained from that are long-lasting.”

Very rarely can local productions compete with international rates offered by the likes of Amazon and Netflix, but television shows don’t film all year round. Local crew, having earned good money for a season, may turn to New Zealand productions to scratch their creative itch. Sometimes the relationships are direct and immediate, like when Oscar-winning production designer Grant Major had just wrapped on King Kong and worked on a local short film produced by Gracewood, for virtually no fee.

Oscar-nominated producer Chelsea Winstanley knows full well the disparity between Hollywood productions and New Zealand productions. She says paying local crew for local work compared to Avatar and Lord of the Rings is “basically asking them to work for a box of beers”.

“I don’t blame crew for taking these big jobs because they have to eat and live,” she continues. “But it sucks when you have fucking James Cameron at those Kea Awards going ‘You know, there’s just no grips’. Dude, the reason why we don’t have enough is cos you fucking take them all!” (What Cameron actually said after receiving the Kea World Class Friend of New Zealand Award in June this year was, “Where we need to invest is in makeup artists and riggers and dolly grips and things like that. We don’t have enough crews to satisfy the major productions that could bring literally billions into our economy here.”)

Winstanley proposes a solution. “If [Cameron] was really serious about that and wanting to call this place home, which he does, and invest in our film community and make it sustainable and allow us to actually make a living, then throw a million bucks at those roles that you are literally scooping. Throw a million bucks at training people up. Put your money where your mouth is.”

“When you can say there are economic benefits and there’ll be stars walking around in our midst, pissing in the bucket fountain and eating our great restaurant food, we get excited about it.”

Local productions receive grants too. In fact, New Zealand film and television projects can qualify for up to 40 per cent rebate on local (which is usually all) spending. But even so, the amounts pale in comparison to the spending on international projects. Taika Waititi’s Boy cost just over $5 million to make and received $2 million from the NZSPG. “It feels like peanuts versus caviar,” says Gracewood.

There are ways of lessening the chasm between the hundreds-strong productions from overseas and the barely-scraping-by productions from right here. For example, an ecosystem that allows props and used film sets to be recycled and used at little-to-no cost to young local filmmakers. Or a direct bridge between crews working on international and local projects, with major studios paying select crew members extra days to work on a low-budget local production, giving emerging filmmakers the chance to work with experienced crew. “The aim should be for us to get to a point where we’re not reliant on international productions,” says Armstrong.

“We can’t welcome the international big guns at the expense of our own local storytellers,” says Liang. “That balance is missing. Yes, the economical benefit is really, really important. But is it more important than us being able to tell our own stories?”

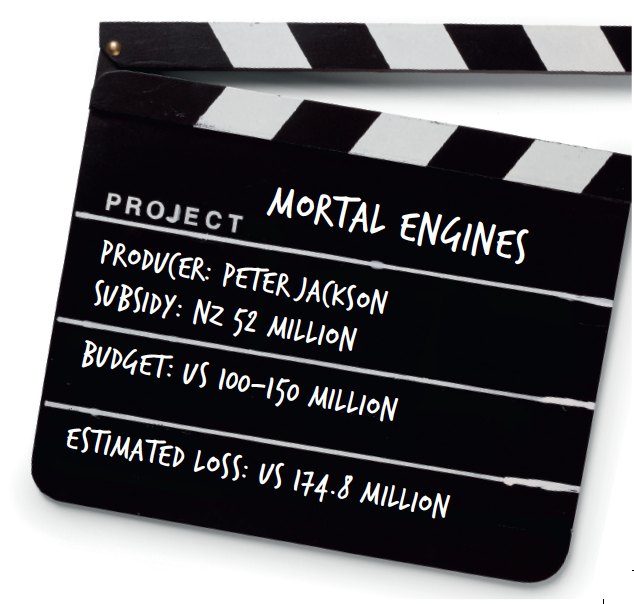

And what about Jackson’s own stated desire to return to telling more of those “New Zealand stories”? Since announcing that intention back in 2014, he has directed two films: They Shall Not Grow Old, a World War I documentary released in 2018, and The Beatles: Get Back, a 6-hour documentary series about the making of Let It Be, which is scheduled for a November release. Another Tintin movie has reportedly been in development for a decade now, with Jackson expressing interest in directing it. He wrote and produced Mortal Engines, a 2018 epic fantasy that was deemed a critical and commercial flop: it received $52 million from NZSPG and lost an estimated US$174 million at the box office.

It’s now been agreed that were the subsidies to cease, so too would the New Zealand film industry as we know it. Jackson himself has said that without the 20 per cent rebate, most if not all of Weta Digital’s major film work would dry up. It’s a grim sign if one of the world’s leading visual-effects houses can’t get work without massive government assistance.

Which creates a Catch-22. For spending hundreds of millions of dollars a year on international films, New Zealand gets thousands of jobs, an increasingly skilled workforce, and growing infrastructure for movie making. But if the subsidised projects disappear, so do the jobs. More film infrastructure simply increases the reliance on more Hollywood giants making their movies here. This in turn drives up the cost of the NZSPG, because studios will only come here if incentivised, all while taking the huge profits of these projects back overseas. International filming here expanded greatly after the subsidy was increased from 15 to 20 per cent. In such a competitive market, it’s only a matter of time before another country ups the ante.

In his 2018 meeting with Ardern and Parker, Jackson assured government officials that there was no need for a cap on the scheme as New Zealand quite literally doesn’t have the capacity for more than two or three major productions at once. But if one of the benefits of NZSPG is industry building, then New Zealand’s capacity to accommodate large projects will grow. That means more big-budget productions will be able to apply for the scheme, leading to higher and higher payouts every year.

While projects like Lord of the Rings and Avatar provide short-term boosts to the economy and local film industry, there’s still no proof of or plan for sustainability outside of NZSPG.

With government agencies and local councils operating according to the whims of giant global corporations, it’s worth asking whether NZSPG is creating the kind of film industry that benefits New Zealand rather than overseas parties. At $200 million a year, it’s no small investment. By comparison, a 2018 Ministry of Health report calculated it would cost the government $148 million per year to provide free dental care for all New Zealanders. So why not spend this money elsewhere?

Middle Earth, that’s why.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern at Hobbiton in 2018. Photo: Stuff Ltd.

In our nation’s capital, Smaug the Dragon still guards the entrance to the airport. The Great Eagles of The Hobbit trilogy still fly over the departure lounge. They were installed in 2013, shortly after the giant sculpture of Gollum was removed from the ceiling.

For two decades, New Zealand has traded on hobbits and wizards and dragons. Planes covered in branded decals, multiple Air New Zealand safety videos, tours, exhibitions, random props and sculptures all over the country. Hobbiton. The mortifying period in 2012 when international visitors received an additional visa stamp in their passports reading “Welcome to Middle Earth New Zealand”.

For years after LOTR, tourism boomed and being a New Zealander abroad meant being asked about one thing and one thing only. But in the years since, New Zealand has made headlines around the world for many other achievements. For a while, Flight of the Conchords was our most popular export. Then Steven Adams. Then Lorde. Then Taika Waititi. Then Jacinda Ardern and our world-leading Covid response.

Yet still we return to Middle Earth. Even after the news of Amazon’s departure was made public, Wellington Airport insisted that the Hobbit sculptures would remain on display in the terminal. We will get one last opportunity to milk the Tolkein universe when the first season of the LOTR show airs in late 2022, before the rights move to the country where the books were actually written.

Had Amazon honoured its agreement and filmed all five seasons here, New Zealand would have spent 30 years and counting moulding its national identity around a piece of fiction that has no connection to this country. Instead, we’ve been given an opportunity to rebrand. There are New Zealanders about to graduate from university who weren’t even born when The Fellowship of the Ring was released. What will their New Zealand be known for instead?

In my conversation with Stuart Nash, when the Amazon deal was still on, he would have been thrilled to see New Zealand remain Middle Earth forever. “You go into Wellington Airport and you’ve got to admit that massive eagle with a wizard on top, that’s pretty cool,” Nash said. I demurred, suggesting that perhaps an airport could just be an airport. “You’re far too young to be that cynical,” he countered. “My kids come into Wellington and that eagle — kids love that. It is outstandingly good.” I asked Nash if his kids love the eagle because it’s a giant bird, or because they love The Hobbit.

“No,” he said. “They haven’t seen The Hobbit.”

Madeleine Chapman, a former North & South senior editor, is the incoming co-editor of The Spinoff.

This story appeared in the October 2021 issue of North & South.