WHANGANUI

Bath and Beyond

The second life of a dilapidated swimming pool.

For almost 100 years, the Gonville Swimming Baths were a highlight for the children of this working-class Whanganui suburb — a meeting place over summer, the pool so crowded at times that it was impossible to stick an arm out without touching someone. The baths’ distinctive façade, designed by local architects Earles, Lamont, Bycroft and Partners in 1974, added to the fun: a collection of toytown peaks that resembled the work of Ian Athfield. Modernism had come to the local pool. But all those years of splashing about took their toll; the concrete began to go spongy and the pool no longer held water. In central Whanganui, the more exciting Splash Centre opened with hydroslides, spa, sauna and café. The Gonville complex’s best days were, well, gone. When it closed in 2005, it seemed destined for the wrecking ball. And yet, this year, it opened its doors again in an incarnation no one saw coming. It is now the Gonville Centre for Urban Research (GCUR).

The GCUR is the work of Whanganui locals Frank Stark and Emma Bugden. They bought the building in March, focused on the large pool, but got much more than they bargained for. “It turns out it was buy one, get two free — take it all,” says Stark. The neighbouring former fire station and out-of-use community hall were also part of the package. “We didn’t expect to own a whole CBD!”

Stark reckons that any building, if you look at it long enough, will tell you how it can be used. He and Bugden have turned the old changing sheds into a gallery, reading and research room and small library of periodicals, art, architecture and design books. Their aim is for it to be a community space for writers and researchers. The changing room seats have been repurposed as bookshelves. The pegs for togs and towels have been partially sawn off and from them hang spare and atmospheric photographs of Wellington’s lockdown, the work of photographer Andrew Ross. Where some might see a cluster of old buildings well past their heyday, Stark and Bugden see potential. They envisage the GCUR holding more exhibitions, being a venue for talks, conferences and screenings, and housing a micro publishing house and printery. The fire station will be a dwelling, perhaps to rent out. This was once the hub and centre of a community and they hope to make it that way again.

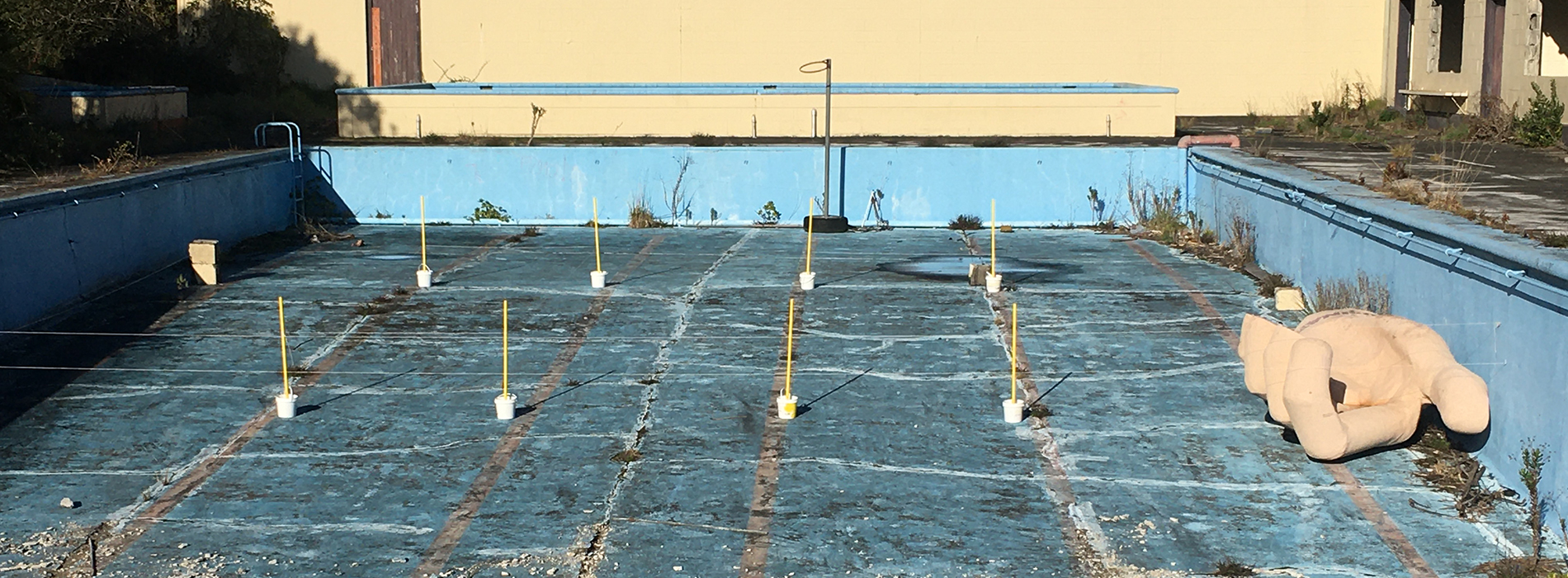

As for the grand pool itself, work is under way to turn it into a community garden. A blog tracks its progress and outlines some of the things that need to be considered. The depth of dirt required to grow fruit trees, for instance. Or how much drainage is needed. And what about the impact of years of heavy chlorine use? Is it possible to grow things in what will essentially be a giant planter pot? At present the most prominent feature is a huge beige hand — a prop of some kind. Undeterred, Stark points to a corner of the pool where weeds sprout from a clump of dirt. “See that? I only put that dirt in there two weeks ago and look at what’s already grown.” He and Bugden might plant fruit trees, vegetables and herbs.

For all this change, Stark and Bugden still have a swimming pool in their plans, and they want to continue to use one of the smaller pools in the complex. “That will be our family pool,” says Stark.

The couple also plan to build from scratch a house next to the pool-slash-garden. Asked where it will go, Stark says, “You’re standing on it! I think you’re standing right where one of the bedrooms will go.”

“We want to build a house that looks like it belongs here next to this swimming pool, using low-price materials. We’re not trying to gentrify it, we are just trying to update it while still fitting in.”

In her book Gonville: The Community by the River, local history writer Laraine Sole says Gonville’s name has its roots in academia, coming from the University of Cambridge in England. “It was an ambitious name, perhaps even a little pretentious,” she writes. Stark concedes that his title, the Gonville Centre for Urban Research, could be accused of something similar. Smiling, looking over his site, he says, “It implies a grandiosity but it’s all very tongue in cheek.”

By Kiran Dass

This story appeared in the October 2021 issue of North & South.