Culture Etc.

Above: King’s Theatre seats, Stratford. Photo: Courtesy of King’s Theatre

Reel Life

The rich and often surprising history of small town independent theatres.

By Tom Augustine

When I tell Ron Slater I want to talk to him about how important rural cinemas are in their communities, he replies saying I’m “talking a load of hot air”. He’s only half joking. Slater is the appealingly gruff owner of the Whangamata Cinema, a bright pink slab of a building with a distinctly “late-20th-century Kiwi oddity” vibe. It still shows films daily, at least during the summer holidays. When I visited our family bach (now long-gone) as a kid, the heat would rise off the tar on the main strip and the old cinema would beckon, posters promising action and adventure roasting behind thick glass windows. After years under the blistering New Zealand sun the cinema is a less virulent shade of pink. And, like many independent cinemas in recent years, it’s for sale.

Slater has worked in the industry for more than 50 years and while he’s owned numerous cinemas over the years, Whangamata is the one he’s had for the longest, and it’s the only one he still personally manages. He describes the business as a labour of love, which I’d come to find was a recurring refrain from small-town cinema owners. “It’s barely enough business to stay afloat,” he says. “The people of Whangamata appreciate it, but y’know, we only really get a handful of people at any given time.” In fact, Slater doesn’t seem to think there’s a place for cinemas in rural communities these days. “I think they’ll just end up in the cities . . . and that’ll be it.”

Indeed, there are any number of threats to independent cinemas, all of them well covered by now: smaller audiences (especially in rural areas with dwindling populations), distribution chains with increasingly stubborn release deals, the deregulation of the cinema industry, the advent of streaming, to say nothing of the Covid-19 outbreak that stalled big-name Hollywood releases for the foreseeable future, while also seeming to break the habit of regular moviegoing for a lot of people. If these threats finish the job, it’ll be an enormous cultural shame. Small-town New Zealand cinemas just feel different to any other kind of moviegoing experience. The sense of history these places bear creates a uniquely warm environment in which to experience a film. While some are housed in old town halls or other similarly utilitarian buildings, the country’s oldest cinemas were modelled on classical opera and music halls, pumped up with a slightly kitsch sense of old-world decorum and grace. Somewhere you could watch Gone with the Wind or Lawrence of Arabia and be swept up in the pomp and circumstance of it all. The history of these cinemas is baked into the walls themselves, the old movie-houses lending some majesty to main drags which are often otherwise blandly modern.

In Geraldine in the 70s, the cinema’s screening lineup used to include a pornographic “Blue Movie Sunday”, showing four nudie movies back to back.

1st Cinema operator Mr Cuth Knight with a promotional car advertising “talking” pictures in Geraldine, 1931.

Every owner is eager to regale me with stories of the intricate and quirky histories of their beloved cinema. In Geraldine in the 70s, the cinema’s lineup used to include a pornographic “Blue Movie Sunday”, showing four nudie movies back to back, just in case one wasn’t enough for your Sunday. A piano used during the silent film era in Taihape was rescued from an ignominious fate in a nearby paddock; given away, then rescued and returned. Mik Symmons, former chairman of the Village Theatre Society in Takaka, explains the patience that was once required by audience members in the days of film projection. “Things would go wrong,” he says, laughing. “Smoke would fill up the projection room, the reels would melt and produce a crazy light effect on the screen. It would get so hot in there that the projectionists would be working in their underwear back in the days before air conditioning.” Many owners are convinced ghosts haunt their buildings. This too, is the magic of the movies.

Geraldine’s cinema first opened back in 1925. My uncle would’ve gone to the pictures there. The first film it showed was North of the Yukon, a silent John Ford picture. When the original owner converted it to sound in 1931, he built his own sound equipment from scratch. The current owner, Patrick Walsh, tells me how the cinema closed following the advent of television in the 1950s. When it was rescued and renovated in the 1980s, the new owners decided to bring in second-hand couches — getting a headstart on a trend that would sweep small Kiwi cinemas in the coming years, although that hasn’t been enough to boost its dwindling patronage.

“Geraldine has gone from being a farming community to a touristy, arty-farty kind of place. You get a lot of tourists who like to come in and take photos of the walls and the carpet and the old posters and projectors, but they don’t watch the films.” The community in Geraldine, Walsh asserts, loves the cinema, but they just don’t go anymore — perhaps because they can’t afford it, or because they’ve been given better options for entertainment elsewhere.

Walsh now seeks out titles that appeal to Geraldine’s growing population of retirees, the cinema’s most reliable customers. They like Kiwi-made films — Hunt for the Wilderpeople was huge — and tend to eschew blockbuster hits. This wasn’t always the case, with Friday night double features for teenagers a mainstay of the not-so-distant past. “The movies would be months old by the time they’d get them, but they’d run something like The Fast and the Furious or 10 Things I Hate About You, and all the teens would be here. It’d be packed and yeah, there’d be fornicating and they would smuggle in alcohol and cigarettes and there’d be fighting outside because all the boys would come from Temuka because they wanted to sleep with a girl from Geraldine.”

Cinemas as a site of romantic awakening for eager young Kiwis is not unique to Geraldine. At the Village Theatre in Takaka, projectionist Benji Wick reflects on how few teenagers seem to go for a night at the movies compared to when he was in high school. “I often wonder where they’re going on dates now,” he says.

Interior of Everybody’s Theatre, Opunake.

The Majestic Theatre in Taihape, built in 1917 and one of the oldest buildings in town, is run by Simone Simpson. A self-proclaimed “farmer’s wife and cinema manager on the side”, she saw the job listing and thought, “That will work with the farming.” Plus, she’s a social person, and the place operates as something of a community hub. Parents drop their kids off during school holidays — they know Simpson will look after them while they’re at work.

Simpson still remembers how the community stepped in to save the Majestic 30 years ago. “They had a wrecking ball in front of the cinema ready to go. And the townspeople realised what they were losing and literally stood in front of the cinema and wouldn’t move.” The crowd warded off the cinema’s destruction and raised enough money to buy it off the council. Today, Simpson works to keep the people’s cinema serving the public who saved it. “We had a young man who wanted to see the Six60 film and I told him that he needed to get enough people together who wanted to watch it to be able to pay for the fees to screen it.” He rallied the troops, and the screening went ahead.

Marlene, who asks to go by her first name only, is part of a group of seniors who make the 40-minute drive from Ohakune to Taihape to visit the cinema regularly. There was once a cinema in Ohakune — indeed, the building still remains, set to become a craft brewery — but the big screen is long gone now. “I actually cancelled Netflix,” she says. “When you’re in your own home environment, sitting and watching something for hours loses its appeal.” Marlene will typically bring a group down. “We’ll try and fill a few carloads. The drive isn’t a hardship.” In fact, it was more than worth it to see the recent Australian farming comedy Rams. “We’re all half in love with Sam Neill so that was very exciting. A few went more than once.” Marlene believes something is lost when a cinema leaves a small town. “Rural populations are very resilient, but we do like to do the things that are available in the cities from time to time.”

The Majestic Theatre, Taihape.

One way to stave off closure is to follow the example of the King’s Theatre in Stratford, which has been turned into a not-for-profit institution. Held in the care of a local trust chaired by Jason Kowalewski, the King’s Theatre is both a space for great movies and a site of cultural heritage since it opened in 1918. It was the first cinema in the Southern Hemisphere to play talking movies, Kowalewski says. Three other theatre owners I spoke to (Everybody’s Theatre in Opunake, the Gaiety in Wairoa, and the Village Theatre in Takaka) are supported by similar committee, philanthropic or council-led initiatives.

The cinemas share an air of ageing grandeur — they bear names like the Regent, the King’s — but these elements are countered by an unmistakeably Kiwi air of togetherness. It’s called “Everybody’s Theatre” for a reason. The perception of cinema-going as one for the wealthier classes, a symbol of privilege and pretension, is, I think, a fairly new one — perhaps a result of material reality. It is more expensive to go to the movies than it has ever been. Reform is arguably needed in the Western movie-making model — the price tags attached to the biggest films and the resulting price hikes at the local multiplex — rather than doing away with cinemas entirely.

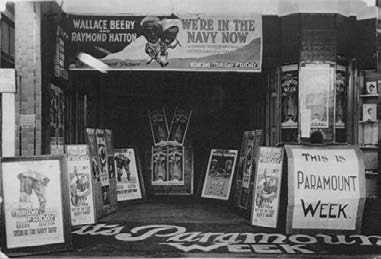

The King’s Theatre, Stratford, during Paramount Week circa. 1926. Photo: Supplied.

King’s Theatre interior, circa 1918.

Cinemas have long been a tool for entertaining, informing and inspiring the masses. The first rudimentary cinematic tools were revealed to the public at fairs and circuses. During the Great Depression they provided an opportunity for the poor and struggling to congregate in spaces that were out of reach at the theatre or the opera. Film audiences far exceed those of many of the other arts.

Most of the cinema owners I speak to are still hopeful that their communities will want to hang on to their cinemas. Simone Simpson tells a story about how recently at the Majestic, a pipe burst, leading to water leaking from the 100-year-old ceiling. “It was like a waterfall through the ceiling. I rang the plumber and he was there in five minutes. The carpet guy came down that same day. They never even charged us.”

Despairing somewhat about the fate of my beloved Whangamata Cinema over the Christmas period, I went to watch the new Wonder Woman film with my young cousins at the cinema in Akaroa, where we were staying. It felt like playing my part in some small way. The Akaroa Cinema Cafe is a modest building, attached to a library. The space has nice big seats and good sound. The movie was fine — could have been better. A month later, the owner posted to Facebook. He had an announcement to make: they were closing down.

King’s Theatre, Stratford.

Tom Augustine is a filmmaker, writer and critic living in Auckland.

This story appeared in the March 2021 issue of North & South.