Poetry for the People

Now 25 years old, New Zealand’s under-recognised Poet Laureate programme democratises an art form that’s typically seen as the province of literary elites.

By Tobias Buck

Left – Tokotoko of past laureates.

Photo : Florence Charvin

Jacob Scott stands and raises his hands toward the ceiling of the marae.

“Eh Māui!” he shouts. “What do you see here? When you see us, just waiting around?”

He pauses. Rocking on his heels. Thinking on his feet.

“What’s it gonna be Māui? What are you gonna do about this . . . this . . . this New Zealand poetry thing? How are you gonna keep it strong?”

There’s a break in his voice on the word “strong” that makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. There’s a charge in the air. A sense of challenge.

“Well I guess that’s your question for us, right Māui?”

Scott looks round at the crowd for half a second before he grins.

“What are we gonna do about it?”

Scott’s biennial check-in with Māui happens 20 minutes south of Napier, at Matahiwi Marae, on each occasion a New Zealand poet laureate is inaugurated. This time it’s David Eggleton, New Zealand’s 12th laureate since the role was created 25 years ago. It’s a bright, cold, Saturday morning at the start of autumn, with everyone wrapped up warm.

Matahiwi is a green marae built in honour of Maui, the innovator. After the blessing there are sandwiches and cups of tea. Outside are fields full of the last squash to be harvested. There might be homemade relish for sale — five dollars a jar, if you’re fast enough. In Hina Taranga, the wharekai, there’s a mural on one wall showing Hawke’s Bay orchards and the old Whakatu freezing works. On another, portraits of some of our country’s finest poets: it’s from here that each New Zealand laureate goes forth.

It’s easy to associate poetry with an ivory-towered literariness. I know I can. The New Zealand poet laureateship was created in 1996 to challenge that perception. It was founded by Tommy Mulligan, kaumātua at Matahiwi marae in Clive in Hawke’s Bay, and my father, John Buck of Te Mata Estate winery. (Our family ended financial involvement with the programme in 2007, and the role is now administered by the National Library). At the time, a lot of countries had laureates — public standard-bearers for language and culture. But New Zealand didn’t, and there was a feeling that poetry here was insufficiently appreciated — especially given our bicultural heritage and the strong oratory traditions in te ao Māori.

Experts at distilling language, a good poet can convey a sense of our national voice faster than anyone. A new laureate might speak at events, tour the country, or publish a book. They might write a blog. Whatever they undertake during their tenure, the award confers a national title, financial support, and a platform to reach more people than ever before — whether that’s speaking at national events or turning poets into household names.

I want to write a poem

like a rusted car wreck,

like a collapsed bridge,

like a random punch,

like a sly foot-tap,

like a Māori haka,

like a fresh death mask,

like peel-off future proofing,

like the smile of a stolen girlfriend,

like the scent of Adieu Sagesse,

like gravestones,

like time-bombs,

fractal geometry,orchestra tom-toms.

I want to write a poem

like the twilight zone,

like righteous incarceration,

like the steady pit-pat of the rain.

The last two stanzas of “I want to write a poem” by David Eggleton. Photo: Supplied.

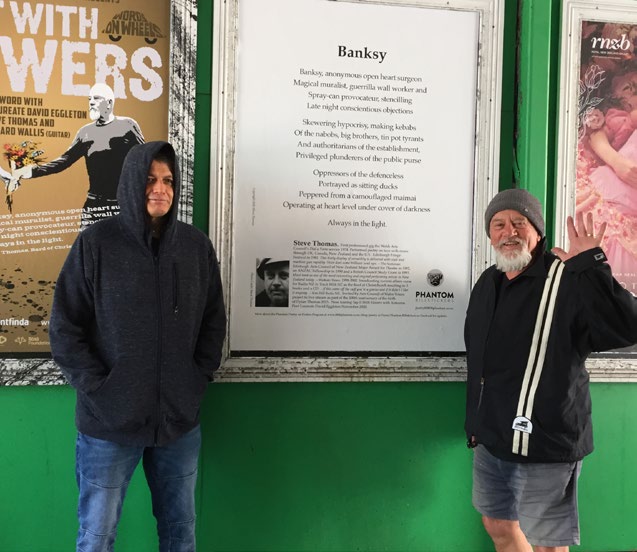

David Eggleton and Steve Thomas stand in front of part of a poetry campaign by Phantom.

The very first New Zealand Poet Laureateship was awarded to Bill Manhire in 1996. Like every poet laureate after him, Manhire received a tokotoko carved by Scott by hand. Scott (Ngāti Kahungunu) is part of Matahiwi and a well-known Hawke’s Bay artist and carver. Manhire’s tokotoko was made from a French oak barrel and topped with a stone from the Tukituki River that runs behind Matahiwi.

Now, when the poet laureates gather you can see their tokotoko together too, reflecting the character of each writer. Brian Turner (the fourth laureate) has one shaped like a hockey stick. At an event once, I saw him casually thwack an imaginary ball off the stage with it. His reading style is as laconic as they get. His insight and eloquence constantly catch the listener off-guard. A line of his has stayed with me since I first heard it: Every New Zealander owns a horse called outrage / and they ride it into the ground.

Rob Tuwhare carries his guitar and the tokotoko of his father, the late Hone Tuwhare (laureate number two). That one is designed to be used as a dip to measure wine in a barrel. Hone is remembered for singing blues tunes until 3am. He could still an audience with his readings, then launch into song, turning it into a joke until he made you laugh. Elizabeth Smither’s tokotoko is appropriately small and elegant, topped with a Holden gear shift and carved whale tooth. Jenny Bornholdt’s has a right angle so practical a carpenter might use it. It brings to my mind the “turned words” of her poems, each adjusted artfully, with incremental shifts in precision and intention.

Before Eggleton, our poet laureate was Selina Tusitala Marsh. At her inauguration in 2018 Marsh performed a dance, the Siva Samoa, that nearly took the roof off with chee-hoos. Elegant and barefoot, she danced with 12 of her family members in a joyous moment of celebration.

Marsh personifies her texts. When she reads, she is dynamic, often performing without notes in an even rhythmic cadence. Just under the surface moves the pushing and pulling currents of connection and colonialism, belonging, identity, and growth. I recommend all New Zealanders watch her reading at Westminster Abbey. As Queen Elizabeth sits close by, Marsh’s poem “Unity” compresses the power and net of empire into an interpersonal exchange. Marsh’s tokotoko extends into a fue, a fly whisk she was gifted by a chief in Samoa. While the poet’s tokotoko may be taonga, an embodiment of prestige and recognition, they have to be portable too. Ready to hit the road as needed. When Marsh met President Barack Obama on a visit to New Zealand, he was as curious to know how she gets it through security.

“Eggleton’s tokotoko is to protect him from the consequences of reciting some of his more provocative poems. “Touch wood, I haven’t needed it for that yet.”

These days, when Eggleton travels with his tokotoko, Te Kore, it is disassembled, bundled up in a tapa cloth bag sewn from the edge-piece of a large tapa mat, with a zipper and strengthened inner-lining. Te Kore is hardwood and encircled with steel rings, embellished with references to Eggleton’s Rotuman and Tongan whakapapa.

“Te Kore means the Void, or Nothingness, out of which arises creation,” Eggleton says. “The Void is charged, full of potential.” Scott told Eggleton its role is to protect him, like a taiaha, from the consequences of reciting some of his more provocative poems. “Touch wood, I haven’t needed it for that yet.”

A life-long advocate for poetry, Eggleton dropped out of high school to self-publish poetry broadsheets. Once considered an outsider voice, Eggleton won London Time Out’s “Street Poet of the Year” in 1985 and became Burns Fellow at Otago University in 1990. He’s also the former editor of Landfall and Landfall Review Online.

After the blessing at Matahiwi, Eggleton has zigzagged across the country with his Say It With Flowers tour, the name coming from street-artist Banksy’s image of a masked activist throwing not a Molotov cocktail, but a colourful bouquet. It’s a rapid-response poetry show, Eggleton says, offering a kind of state-of-the-nation moment, sharing poems with audiences. (He will hold the laureateship for three years instead of the customary two, to allow him to make up for time touring and performing that was lost during Covid lockdowns.)

Eggleton’s known as a poet who likes to provoke. Since 1986, when he released South Pacfic Sunrise, he’s been one of the country’s strongest live performers. The Oxford History of New Zealand Literature describes his style as “a torrent of phrases made up of the savage subversions of the languages imposed upon us”. Eggleton’s readings push back on the dead language of adverts and politics. Hearing him read reminds me of the great New Zealand tradition of experimental art/rock gigs: unpretentiousness mixed with high-art incantation. Elevated yet punk. His reading is rapid-fire, deep and musical. His poem “Grass” opens up, when read, to its full swinging alliteration and rhyme: “Shoulders up to the hills, / the spirit of great-great-granddad slumps / staring at the sun, his stumps / gnawing fat of the land, side of mutton in hand.”

On his Flowers tour Eggleton performed at 20 venues, appearing at Alexandra’s Stadium Tavern and the Queenstown Writers Festival, popping up in Gore, the Coromandel and back down to Takaka’s Mussel Inn, with a house concert in Onehunga and a performance at Tiny Triumphs bar in Devonport thrown in along the way. There was a last-minute concert organised in a home in Rotorua, furniture quickly shifted around, and a lively turnout at the Quiet Dog Gallery in Nelson.

“The role of the laureate was a perfect opportunity to get poetry out there, to stand and deliver to the avid culture vultures in small towns,” Eggleton says. “The audiences that turned out for us were always that. There for us. For poetry, and the communion poetry brings as a go-anywhere artform to communicate mystery and strangeness.”

Just south of Punakaiki on the West Coast, Eggleton arrived early on a November afternoon to the wooden 1920s Barrytown Hall. The afternoon was windy and the town was deserted. Then, just after nightfall, people started turning up from all directions. Out of the rainforest and down from the hills. The locals manifested themselves into a lively venue and rollicking audience. “They lived up to their reputation for fiercely supporting travelling acts that made it all the way to that wild neck of the woods,” Eggleton says.

He is currently working on a longlist for the online anthology Ōrongohau — Best New Zealand Poems 2020, due to be published soon by Te Herenga Waka / Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters. A new collection, The Wilder Years: Selected Poems, is set to be published by Otago University Press in April.

As he works, Eggleton’s tokotoko is near to hand. “Te Kore would encourage any poet to write to make the familiar strange. To quest after the transformative poem. The lightning flash.”

thanks for seeing the earth as a body

the North, its head

full of rationality

reasoned seasons

of meaning

cultivated gardens

of consciousness

sown in masculine

orderly fashion

a high evolution

toward the light

thanks for making

the South an erogenous zone

corporeal and sexual

emotive and natural

waiting in the shadows

of dark feminine instinct

populated by the Africas

the Orient, the Americas

and now us.

The last two stanzas of “Guys like Gauguin” by Selina Tusitala Marsh.

Selina Tusitala Marsh performs at the National Library in Wellington. Photo: Supplied.

In February a national poet laureate was under a global spotlight at Joe Biden’s presidential inauguration. At the Washington event, viewed by millions, the first US National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman read her poem “The Hill We Climb”. A star turn, her poem reflected the sense that hope and redemption were still possible in a divided United States. It began simply: “When day comes we ask ourselves/Where can we find light in this never-ending shade?”

It was personal and direct in a way that political events seldom are. A reminder that here too, a “New Zealand poetry thing” can be both a quiet backyard experiment and a role of immense cultural weight. Our laureates are not just a skilful and diverse bunch. They are living heritage, ambassadors distilled from our own dialects, voices, languages and sounds. They show poetry here is something that evolves and grows just as our country does.

Eggleton is not one to big-note his own success — few involved are. And, honestly, that’s part of the appeal of the whole thing. But 25 years of having a New Zealand poet laureate is a unique landmark in our artistic landscape. We shouldn’t let the quiet nature of the enterprise preclude its significance. It’s a challenge for us too, to recognise poetry as part of our heritage and be proud of it. Māui might be there to kick us along every now and again. But keeping the show on the road is very much up to us.

Waterclosets slip from moorings, cob cathedrals buoy up their bells and melt back into the hills. Water’s clear grain englobes black cherries, as stealthy as fingers flogging food in dairies.

Whitewater froths like hydrophobic dogs at tourists agog on prayer-mat rafts. A flax taproot rots in a brain-sponge corner, Sheds grow green, creeks rock with logs.

Rainbows capsize, bulldozers sink underground. Buckled into space, cars skid round and round. Stopbanks fail, a lake loots a drowned town. Rain drapes all in its pearl-grey bridal gown, Down south, down south, down south.

The last two stanzas of “Deep South” by David Eggleton, from Selected Poems.

Tobias Buck is from Hawkes Bay and lives in the Netherlands. His last story for North & South was about a retired Wellington diplomat who caught a notorious serial killer.

This story appeared in the May 2021 issue of North & South.