Culture Etc.

Above: Aerial view of Rotoroa Island. Photo: Rotoroa Island Trust.

Recovery Island

The site of a longstanding rehab facility in the Hauraki Gulf has become a sanctuary for native species.

By Michelle Langstone

Jo Ritchie was laying tracking tunnels on Rotoroa Island when she began finding glass jars secreted in the foliage. The sanctuary island in Auckland’s Waitemata Harbour was undergoing intensive pest control, and the tunnels, equipped with ink pads and card, were laid to capture the footprints of the species passing by and monitor their numbers. The jars were nestled amongst the large roots of pohutukawa trees, where the shelter of a natural “larder” kept them clean and dry. At first, Ritchie was puzzled. But then she recalled a story she had heard about the history of the island. For nearly 100 years, it was the Salvation Army’s rehabilitation facility, where addicts were sent to overcome their affliction away from the temptations of the mainland. The jars were the remains of secret alcohol production by patients trying to ease their withdrawal symptoms by drinking concoctions made from turnips and other vegetable matter set to ferment with sugar stolen from the facility’s kitchen.

Rotoroa Island is an 82-hectare ecosanctuary nestled in the Hauraki Gulf, east of Waiheke Island. But from 1911 until 2005, it was also New Zealand’s first and longest-running rehabilitation centre. The Vagrant Act of 1866 made habitual drunkenness illegal, the consequence imprisonment. This punitive approach was reconsidered in 1906 and replaced by the Habitual Drunkards Act, whereby anyone publicly drunk three times within nine months was instead to be institutionalised for rehabilitation.

That same year, the Justice Department asked the Salvation Army to provide a facility where drunks could be restored back into functioning citizens, and the organisation bought Pakatoa Island in the Hauraki Gulf for the purpose. After several years the 24-hectare island was deemed too small to keep up with demand, a new island was purchased, and male patients were ferried across a small strait to neighbouring Rotoroa in 1911, leaving Pakatoa free to house women. The terms for patients were anywhere from six months to two years.

Patients tried to ease their withdrawal symptoms by drinking concoctions made from turnips and other vegetable matter.

If you wander inland from Home Bay, the original site of the facility, remnants of its former life remain: 12 huge phoenix palms planted by the Salvation Army tower in the landscape, representing the 12 pillars of their recovery system, a programme similar to Alcoholics Anonymous. Patients helped with fencing, boatbuilding and road-making, tending livestock and growing fresh food. They were encouraged to pray and reflect, though patients argued against compulsory attendance of church, and won. The Salvation Army’s goal was redemption of both body and soul, but not all patients agreed with the process: in 1912, patients wrote to a local paper to complain about the length of the sentences, and the way they were being treated. The physical labour was a shock to some. And despite the remote location, patients found ways to access alcohol. Patients were found visibly drunk after spending time in the gardens, where rudimentary alcohol stills were eventually discovered.

In 2005, the Salvation Army disestablished the facility for good, moving its Bridge programme to the mainland, in keeping with the new wisdom that recognised closeting addiction away from society was ultimately not as effective as more integrative measures. Its legacy was 12,000 patients treated. The vacant island caught the attention of Neal and Annette Plowman, an Auckland couple who had enjoyed financial success in the laundry business. The Salvation Army drew up a 99- year lease, the price estimated at many millions of dollars, and the couple became the new custodians of an island that would now be focused on a very different kind of recovery.

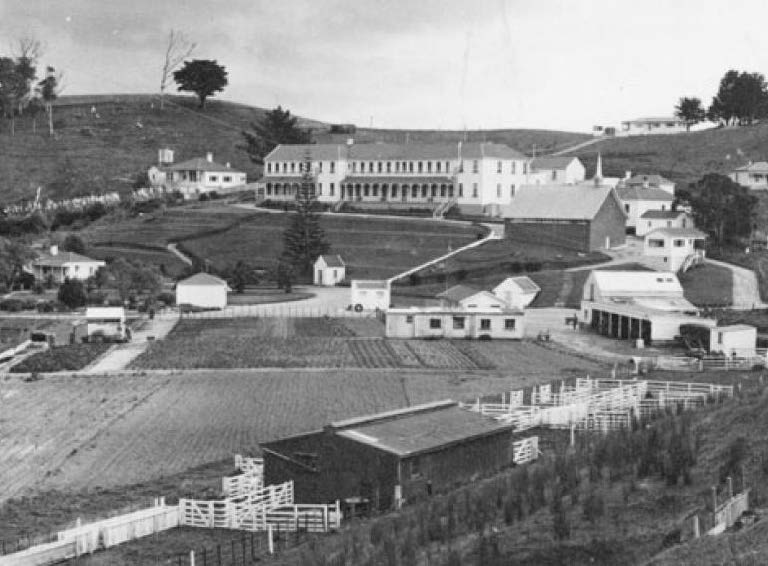

The Salvation Army facility on Rotoroa Island. Photo: Salvation Army.

A century had passed without public access to Rotoroa. The Plowmans’ goal was to restore the land to its former condition and bring back species that could help it thrive as a modern sanctuary. In accordance, many of the asbestos-riddled buildings have been torn down, along with the pine belt that wrapped the crest of the island.

With a landscape design from Boffa Miskell, work began on enriching the soil, which Ritchie, the island’s Operations Manager, says was hopeless — salty, claggy with clay, and devoid of nutrients. Since the Rotoroa Trust was formed, 400,000 native trees and plants have been planted, including pōhutukawa, karo, mānuka and kānuka, harakeke, and tī kōuka (cabbage trees). It was trial and error for Ritchie, watching to see which species would survive the wind and the salt. Native saplings were “spinning in their holes’’ from the wind that raced down the hillsides, when the windbreak provided by the pine trees was gone. Only the hardiest coastal species have survived, their thick leaves tough enough to withstand the salt and create a protective layer for softer shrubs like kawakawa to grow on the forest floor. Rotoroa’s limited fresh water supplies mean the trees have done it tough: watering them, says Ritchie, would only create a dependency. Like the island’s former patients, the trees are drying out, but enduring.

The first time Ritchie heard a cicada sing on Rotoroa, she got a fright. Now the bush thrums with life.

When Ritchie and the Rotoroa team began planting, the island was eerily silent. Rats, faced with limited food sources, had decimated the insect populations on the island. The first time Ritchie heard a cicada sing on the island, she got a fright. Now the bush thrums with life and the pollinators are out in force. The island acts as a “creche” for juveniles of endangered species like the takahē, brown kiwi, and pāteke. Kiwi are reared to maturity before they are moved elsewhere to breed, and the resident takahē, Fyffe and Mulgrew, are raising their baby Rataroa before it is sent to the Department of Conservation to participate in breeding programmes to extend the population’s gene pool.

These birds are only able to thrive on Rotoroa because it is predator-free, and the work to keep pests out is relentless. A kiwi chick release scheduled for early January was cancelled when a boaty at anchor in one of the bays reported seeing a stoat swimming ashore. One hundred and twenty traps were laid and are checked every few days. The chick will wait until the stoat has been destroyed before it joins the island’s population.

There were no possums on the land when the trust and its partners began work. Early on, a rat eradication programme was underway when it was discovered they had made huge nests under the pine mulch from the thousands of felled pine trees; they loved the warmth and safety of the thick blanket of decaying matter. After the rats were gone, the mice took over, before they were eradicated with an aerial poison drop. The island has been largely predator-free since 2009. Today, tīeke (saddleback) thrive on Rotoroa, dripping from the trees with their chatty song. Weka engage in petty theft of the belongings of visitors, and pōpokotea (whitehead) and tūī are in healthy supply. It’s not uncommon to share the walking tracks with weka, or glimpse the takahē in the distance as you traverse the island. It’s remarkable to see endangered species thriving in the company of humans, but Ritchie says there has never been a problem with visitors disturbing the birds: people who come to the island can feel what a gift it is to walk alongside them.

A tīeke in flight. Photo: Courtesy Rotoroa Island Trust.

Jo Ritchie with a kiwi chick. Photo: Courtesy Rotoroa Island Trust.

That Rotoroa can be walked across at all remains a novelty for much of Auckland’s boating community, who were barred access from landing on the island for the near-century that the Salvation Army was operating the facility. “Landing prohibited” signs decorated the shorelines. Boaties who anchored offshore at Home Bay could observe inhabitants moving about their daily life, working, or taking constitutionals along the shoreline. Sometimes patients would swim out to boats looking for an alcohol fix from daytrippers. (Men also swam the 724-metre strait between Rotoroa and Pakatoa Island for illicit trysts with willing women patients there.)

There are many hope stories, as well as despair stories. For Trevor Williams, Rotoroa was both. The alcoholic entered the facility as a patient in 1987, but when he finished treatment he found himself struggling to reintegrate into his old life. Drunk on his first night back home, he begged to be allowed to return to the island. A former cabinet maker, he eventually found gainful employment working on boats, learning plumbing, dealing with the sewerage systems and staying sober. He remained living on Rotoroa as it began its transition to a sanctuary. Ritchie says that his deep knowledge of the island has been invaluable.

The Rotoroa Trust still works closely with the Salvation Army, and sees itself as the kaitiaki, or guardian, of the island for the duration of the 99-year lease. After that, the hope is that revenue from visitors will make the island financially self-sufficient, and the sanctuary can flourish, independent and fully recovered.

A sign informing visitors of the Rotoroa sanctuary’s no-pets policy. Photo: Courtesy Rotoroa Island Trust.

Michelle Langstone is a North & South contributing writer.

This story appeared in the March 2021 issue of North & South.