High Growth

How hemp went from a niche interest of hippie enthusiasts to an industrial cash crop with serious market potential.

By Oliver Lewis

It was described as a valueless bog. When John Grigg and his brother-in-law bought land in Mid Canterbury in the latter half of the 19th century, people thought the site was little more than a big swamp — sodden and unsuitable for farming. But Grigg, a recent English immigrant to New Zealand, was undaunted. He drained the land and established a thriving 13,000 hectare property bounded by water on three sides: the Ashburton and Hinds rivers to the north and south, and the Pacific Ocean to the east. Longbeach Estate became a vibrant station and a major local employer, with its own school, chapel, store and brickworks. In 1882, the farm provided part of the cargo for the first shipment of frozen meat bound for England, a pivotal moment for New Zealand and a future cornerstone of the economy. In 1954, Queen Elizabeth II — the first reigning monarch to visit Aotearoa — stayed during her coronation tour. Through hard work, the site had been transformed.

James Thomas is a descendent of John Grigg, and the sixth generation of the family to farm at Longbeach Estate. The 34-year-old, a genial, down-to-earth man in solid work boots and a checked shirt, runs the property with his parents Bill and Penny and his wife, Rachel. The property is smaller now, about 1170 hectares. Historically, most of the land has been planted with crops — staples like oats, wheat, barley and grass seed — but the farm also runs livestock and a herd of dairy cows. Recently, it began growing something a little different.

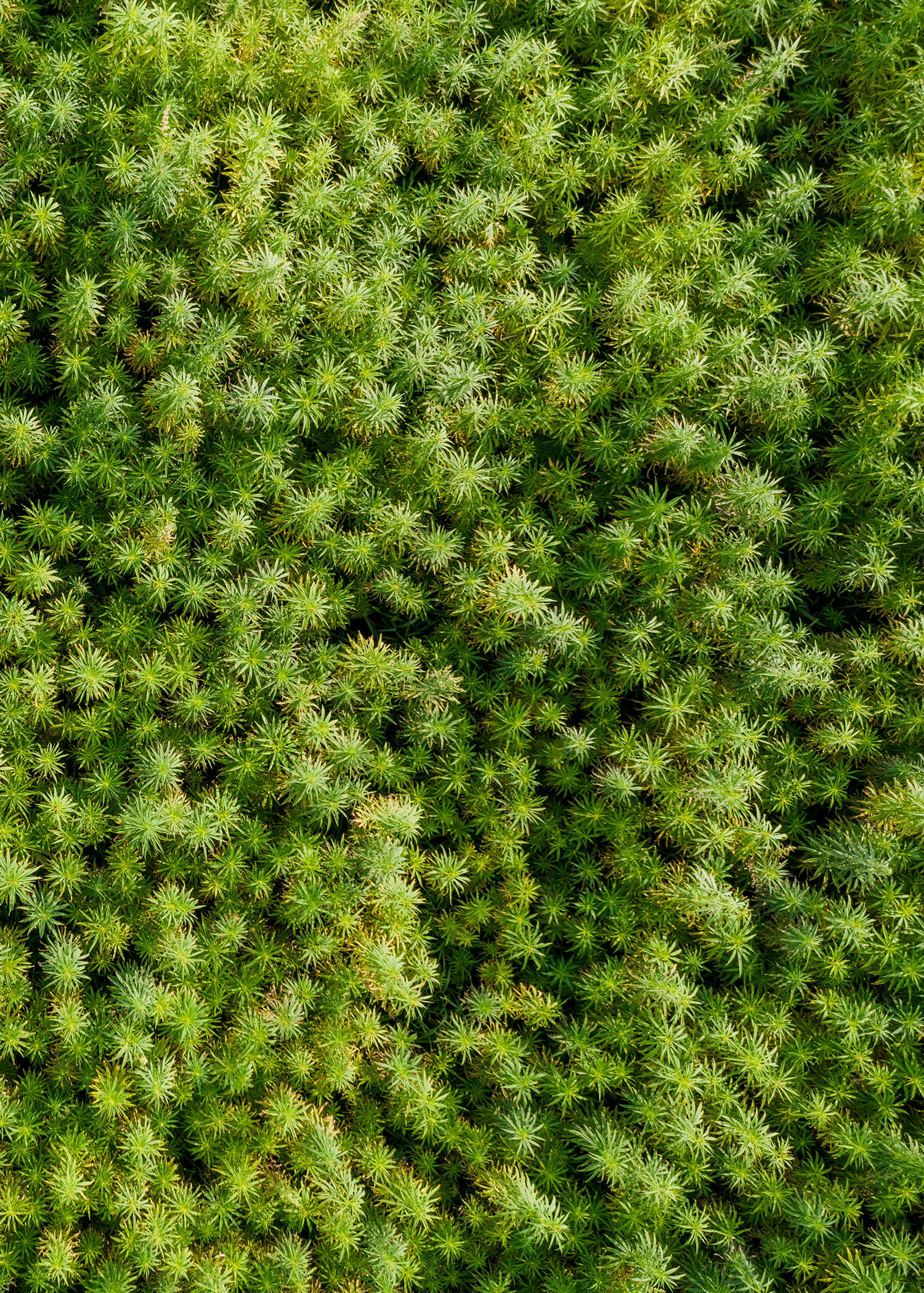

There are 40 cropping paddocks at Longbeach, but it’s one in particular that’s of interest when I visit in early February. After driving past some of the historic brick buildings, Thomas arrives in his ute and leads the way, heading back inland towards the mountains visible on the horizon. We get to the paddock and the young farmer reaches out and picks a leaf, crumbling it between his fingers. Above him, the tall stems and tops of the plants sway in the breeze — dense, green and immediately recognisable: Some visitors are interested in the plant for its sustainability credentials, Thomas says, while others simply want to appreciate the visually arresting sight of 20 hectares of Cannabis sativa, the equivalent of about 20 international rugby fields. “Everyone’s keen to see a big field of what looks like dope growing.”

Longbeach Estate in its earlier days. The same family has been farming here for six generations. Photo: Courtesy of the Thomas family photo collection

It’s taken more than two decades for the hemp industry to develop from a niche, slightly hippyish horticultural interest to an industrial cash crop with serious market potential. Discussions on the subject can be prone to a bit of hyperbole. Some advocates are evangelical about hemp’s potential, describing it as a kind of saviour crop, a natural alternative to petrochemical products and processed foods. Still, for a long time, hemp growing was a small and artisanal affair. One scientist describes the mix of people at a hemp conference a few years back: scientists alongside alternative lifestylers, some looking like they had teleported straight from a 1970s commune.

From the late 90s, industry body New Zealand Hemp Industries Association (NZHIA) campaigned for hemp to be grown legally, and for its seed to be sold as food, emphasising its health benefits. In 2006, the government changed the law to allow farmers to grow hemp under licence, but the sale of edible hemp seed was still banned. Successive governments were keenly aware of public perception linking hemp with cannabis, the drug. This is despite the fact that, by law, industrial hemp can contain no more than 0.5 per cent THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) — the main psychoactive component found in marijuana — and generally contains less than 0.35 per cent. Ten years later, in 2016, the licences covered only about 65 hectares.

Some visitors want to appreciate the visually arresting sight of 20 hectares of Cannabis sativa, the equivalent of about 20 international rugby fields.

Carrfields’ hemp harvester (the only one of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere) motors through crop at a mid-Canterbury farm. Photo: Oliver Lewis.

In 2018, a law change finally allowed hemp seed to be sold as food for human consumption. Then-Food Safety Minister Damien O’Connor emphasised that packaging could not include any reference to cannabis or marijuana, including hemp leaf imagery. Following the law change, the number of hectares under licence skyrocketed to 3978 hectares (though only about a third of that was cultivated). A new market had been created virtually overnight. Analysts calculated that hemp growing could generate up to $20 million in export revenue in its first five years.

As part of their licence conditions, farmers can’t grow hemp within view of the road, meaning this exponential increase has taken place largely out of sight, on farmland scattered about the country. Temperate parts of the South Island with high temperatures and lots of light, like Nelson and Canterbury, offer particularly good conditions for growing. There are even some enthusiasts who have fantasised about hemp replacing intensive dairying on the Canterbury Plains — of cannabis displacing cows. That’s unlikely to happen. Hemp is mainly used by growers as a break crop. Break crops are meant to help reduce disease, weed and pest pressures that build up from growing staples like wheat, barley or ryegrass for too many cycles. Hemp is also an option in paddocks that have been used to winter animals and are flush with nutrients.

Thomas has been growing hemp for two seasons now, both times under contract to Carrfields Grain & Seed, a division of the Carrfields agricultural group. He estimates that he is currently making roughly $2,000 in profit per hectare — pretty good, he says, roughly comparable to other break crops like peas. A neighbouring farm has been growing hemp for years with success, and he was also aware of an increasing consumer interest in natural, plant-based products. “I’d like to grow a crop that’s going to do some good for the world, basically,” he says.

James Thomas stands amongst his hemp crop at Longbeach Estate in Canterbury.Photo: Oliver Lewis.

It’s early in the year and Thomas is going through some sums. The young farmer is standing on a track through a paddock at Longbeach, an unirrigated site with heavy soils. How much nitrogen did he put on the crop when it was sown last November? Very little compared to something like a spring wheat. Hemp is a relatively low-input crop, which may make it more appealing to farmers as they come under increasing environmental constraints.

New Zealand-specific research on industrial hemp is still limited, but studies suggest the plant has excellent carbon sequestration potential, meaning it can suck up and store a lot of carbon dioxide. Hemp has a long, deep taproot system which helps break up and aerate soil as well as catching nutrients other plants may miss, helping mitigate nitrogen leaching. Thomas is growing a specialty variety of hemp for fibre which will be made into things like packaging, weed matting and eventually even clothing. What doesn’t get bailed up will rot back into the soil, releasing nutrients to help the next crop, an essential part of maintaining good soil health.

Inland from Longbeach, a converted forage harvester is scything through another hemp field, the crop buckling and swaying violently under its advance. From high up in the cabin, the scene is hypnotic. Engine thrumming, the 500-horsepower machine plunges through the crop in wide 4.6-metre swathes, pulling in the three-metre tall plants and chopping them into lengths. These stems will lie on the ground for weeks, a process which helps separate the plant’s fibre from its hurd (the woody inner part of the hemp stalk). “This is what you want to be driving in a zombie apocalypse,” the driver says as we monster through the plants.

Hemp crops for seed are short and relatively easy to harvest. Fibre varieties, on the other hand, are tall, strong and difficult. As hemp business manager for Carrfields, Mark Collie oversees the entire operation for the company. According to Carrfields, the harvester is the only one of its kind in the southern hemisphere, specifically configured to harvest hemp for fibre. Watching the machine in action, it’s clear: this is hemp farming at an industrial scale, backed by significant resources. Carrfields is one of the country’s major agricultural groups, built by the Carr family from mid-Canterbury. A powerhouse with multiple divisions and subsidiaries, the company spans everything from irrigation to contracting, livestock and machinery.

Degummed hemp ball. Photo: Courtesy Carrfields.

Dave Jordan, an industry pioneer who has run company Hemp New Zealand since 2008, helped bring Carrfields on board. In 2018, he asked the company to take over the administration of his Hemp Farm grower group, which was contracting farmers to grow the crop. Two years later, Carfields had farmers growing roughly 1000 hectares of hemp, making it by far the single biggest supplier in the country.

At the start of February 2021, there were 180 licensed growers of industrial hemp around New Zealand, including a subset of 19 licence holders who were also granted research and breeding licences. One of these is Midlands, a seed producer headquartered in Ashburton, which Collie and others credit for driving the industry forward in the early days when there was more red tape and fewer incentives. Midlands Seed was granted its first licence to undertake hemp field trials in 2001. Since then the company — the largest supplier of hemp seeds for sowing in the southern hemisphere — has continued to import and evaluate different hemp varieties, going through a rigorous testing process to broaden the range of approved cultivars. Hemp grown for seed or grain now consistently yields more than 1000 kilograms per hectare, up from 700 or 800 kilograms a decade ago, says Midlands director Andrew Davidson. But trials here and elsewhere around the world are already targeting yields of up to 2000 kilograms.

Health and wellness is now a global trillion-dollar industry. One part of that is plant-based food, once the domain of specialty health stores. Meat-free replicas of beef such as Beyond Meat and the Impossible Burger are commonly spotted on supermarket shelves, and all manner of supplements, from collagen to turmeric, have gone mainstream. No longer just a point of principle for those who care about animal rights, vegetarianism and veganism are now often choices made over concern about meat’s impact on human health, and, increasingly, large-scale animal agriculture’s impact on the environment and climate change. Similarly, demand has been growing for hemp oil and food products, from protein powders to cereal products and muesli bars. The seed has been described as a kind of super food, high in protein and essential fatty acids.

Davidson, the Midlands director, says New Zealand’s laws will need to adapt to meet this demand. Both he and Richard Barge, chair of NZHIA, point to a range of stumbling blocks, including the inability to dual crop for hemp seed or fibre and cannabidiol (CBD), a substance with potential therapeutic value which comes under a different regulatory framework. You can grow either, but not both at the same time, Davidson says. Growers are not permitted to sell or use hemp for animal feed, as officials have raised concerns over the risk of THC or CBD showing up in meat or milk sent to sensitive export markets. Rules also prevent over-the-counter sales of products with low quantities of CBD. As a result of these restrictions, growers say they aren’t able to extract revenue from all parts of the plant. Rules around the sale of CBD seem unlikely to change soon after the failure of the cannabis referendum in the 2020 election and the government’s current unwillingness to tinker with drug-law reform.

At the same time, new technology is unlocking more opportunities. In the back of a Christchurch factory, located in an unassuming industrial block near the airport, is an enormous machine called a decorticator that could revolutionise the local hemp industry. It stretches down two walls of the factory. A conveyor belt feeds in bundles of hemp stalks, which get processed and separated into fibre and hurd. At its maximum capacity, the machine can process two tonnes of hemp an hour.

One scientist describes the mix of people at a hemp conference a few years back: scientists alongside alternative lifestylers, some looking like they had teleported straight from a 1970s commune.

When I speak to Colin McKenzie, the chief executive of New Zealand Natural Fibres, in February, the decorticator is still being set up. On his desk, in an office decorated with rugby memorabilia, is a ball of sleek white strands — degummed hemp fibre. For decades, the New Zealand Natural Fibres factory, previously called NZ Yarn, has processed wool into yarn. Carrfields effectively controls the company through a subsidiary that is a joint-venture with a cooperative of sheep farmers. Hemp New Zealand, seeking to establish a commercial hemp-fibre processing line, bought into the company and acquired the decorticator from the United Kingdom. Experts have described the machine as a “step-change moment” for the hemp industry, which has so far sustained itself on oil and food products.

Previously, fibre has been an artisanal pursuit. Now, the decorticator can produce fibre and hurd at scale. The company plans to produce a range of entry-level products from the raw fibre, including geotextiles for land stabilisation and weed matting, and different types of packaging

But it’s the high-end products McKenzie is most excited about. New Zealand Natural Fibres produces bespoke yarn products, mostly for use in high-end carpets. McKenzie says hemp fibre can be blended with wool for use in soft flooring. It can also be used to make clothing, and the company already has agreements with international apparel brands. It wants to produce the hemp fibre and manage the offshore supply chain.

To do this, the raw fibre — scratchy and rough — has to be refined, a process known as degumming. Existing processes are typically chemically intensive, McKenzie says. The race is on worldwide to figure out a more environmentally friendly method. New Zealand’s Ministry for Primary Industries has invested $200,000 in a research and development programme to come up with a sustainable alternative. The processing line has the potential to transform the local fibre industry, making hemp a more viable option for everything from houses (using “hempcrete”), to shirts, food packaging and geotextiles.

In a strange way, for the Thomas family and other farmers, growing hemp is a return to the distant past. When John Grigg established Longbeach Estate, things like hemp ropes and sacks would have been commonplace around the world. One hundred and fifty years later, his descendents are helping to normalise the crop once again. Just like the business of farming itself, it appears tastes are cyclical.

Oliver Lewis is a freelance journalist based in Christchurch with an interest in trains, mental health and infrastructure.

This story appeared in the June 2021 issue of North & South.