Prince of the Commune

The victims of sexual abuse at the Centrepoint community are speaking out — but what about accountability for the perpetrators? John Potter, the son of Centrepoint guru Bert Potter, was convicted of two charges of indecent assault on an underage girl. In this previously unpublished conversation, he gives a rare glimpse into the mindset of an abuser.

By Anke Richter

Illustration: Imogen Greenfield

It took three decades for the survivors to feel safe enough to speak out. This May, in the TVNZ documentary Heaven and Hell, three women talked openly for the first time of their experiences at Centrepoint as children and teenagers. Founded by pest exterminator turned self-appointed therapist Bert Potter in 1977, it was ostensibly a counselling commune on the outskirts of Albany dedicated to overcoming sexual repression. It is now better known as a sex cult. A Massey University study found that during Centrepoint’s 23 years of operation, one in three children who lived there may have been abused.

One reason it has taken so long for this disturbing chapter of New Zealand social history to emerge into the light is that for hundreds of former residents, Centrepoint is not just a salacious scandal. It was their home, and it is still an alive and destructive force in many ways. While many who lived there in childhood were unharmed and hold happy memories, for others unprocessed trauma has led to mental breakdowns, suicides and addictions. Among those still in contact, the community is split into numerous factions. There are children aligned with their pro-Centrepoint parents, others who are vocal or angry and some who try to negotiate between them. There are perpetrators and victims in the same family; sometimes in the same person. Before the documentary aired, I heard stories about silencing in prominent Centrepoint families that were almost as disturbing as those about the cult itself. The shame runs deep, as does a lingering “us versus them” mentality.

No convicted sex offenders appeared in the documentary. (I was a research consultant on the project.) Of 60 adults we contacted, four came on board. One man expressed remorse for not doing more to protect the younger ones. Another woman said, “I didn’t realise that good, kind, loving people could also be sexually abusive.”

Given that only about a dozen Centrepoint abusers ever faced charges (some with name suppression), the lack of accountability remains a major obstacle to healing for some survivors. A restorative justice effort for children of the community called the Centrepoint Restoration Project is underway, led by a Christchurch doctor, and an Auckland therapist is offering workshops.

The silence of the perpetrators has also prevented a wider understanding of how Centrepoint could have happened here. Its founders were doctors, nurses, teachers, psychiatrists and other middle-class professionals who wanted to heal what was broken in them. How did this idealist undertaking come to break so many others?

Only one Centrepoint offender has ever spoken about his actions: John Potter, Bert’s son, who was seen by other residents as the “prince of the commune”. He moved there in 1978, when he was 19. He left after seven years and later returned with his second wife, Felicity Goodyear-Smith. The couple lived next to Bert from 1988 until 1990, when Bert was arrested and sentenced to three-and-a-half-years in prison on drug charges. In 1992, he received a further sentence of seven-and-half years for the indecent assault of five children. John pleaded guilty to the assault of underage girls and was imprisoned for four months. Bert died in 2012, and at the funeral John apologised on behalf of his father, as well as “anyone hurt by either my actions or inactions”.

I interviewed John Potter two years later, while researching a book about Centrepoint. At the time, I was startled by his willingness to speak openly on the record of his sexual interactions with underage girls. One was Louise Winn, who moved to Centrepoint when she was 10 and was assaulted by Bert and later John. She tried to kill herself when she was 12. Winn was among those who later laid charges against both men. Before Bert’s trial, she says, a Centrepoint “delegation” visited her and “intimated I would hurt a lot of people if I went ahead”.

My interview with John Potter was never published: the book project folded. But with the voices of Centrepoint survivors finally being heard, that conversation with the guru’s son offers an insight we almost never get into the mindset of an abuser who is still learning to understand the harm he has done.

Potter is now retired, a father of three. He and Felicity still live in Albany, together with Suzanne Brighouse — Bert Potter’s “thought police” — who also served a prison sentence. Over the years, Potter and Goodyear-Smith have been active in groups that claim sexual abuse accusations are often exaggerated or invented. Goodyear-Smith, a professor at Auckland University’s medical school, is the author of the controversial book First Do No Harm: The Sexual Abuse Industry. Potter is the webmaster for the “masculinist” site MENZ. He also set up a members-only “Centrepoint Community” website — an archive for Bert Potter’s talks and a place to keep memories alive.

This May, when more than 50 adults, including John Potter‘s first wife, signed an open letter asking for accountability, I asked him whether he had changed the views he expressed in the interview about his sexual encounters and his interactions with Louise Winn. “No” was his answer to both questions. He added that he would apologise privately to former members of the community “if that would help their healing”.

Our “peace meeting”, as he called it, took place on a sunny autumn morning in 2014, on the grounds of the former Centrepoint site. John, an avid cyclist, arrived by bike. Then 57, he had a shaved head and wore a single earring. We sat on the grass in the Glade, where adults and teens took ecstasy together in group experiments and where Potter got married twice.

At times during our three-hour conversation, which I recorded, Potter expressed remorse. But he was also visibly startled when I told him of Winn’s ongoing trauma, saying: “I find that pretty surprising that I would be such an important part of her life, when I can barely remember.”

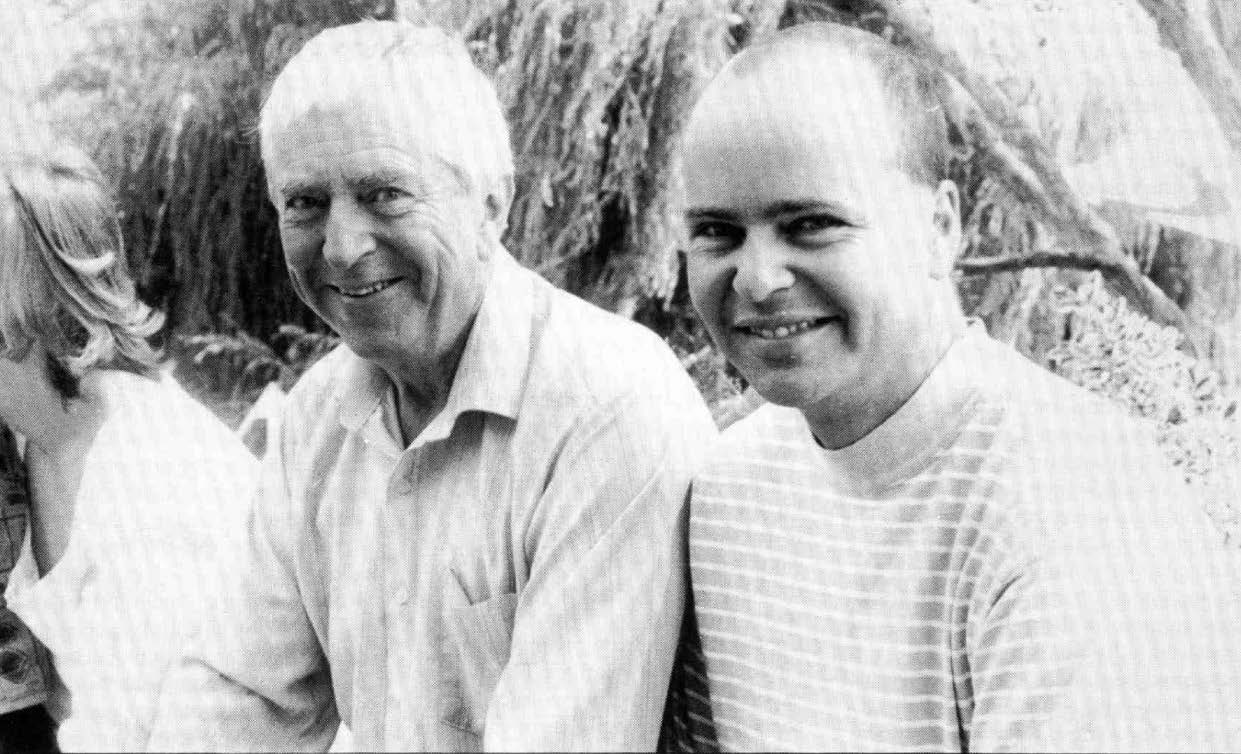

John Potter and his wife Felicity Goodyear-Smith in 2011. Photo: Adrian Malloch.

Anke Richter: I’m surprised that you were open to talking to me, especially about sexual abuse, unlike others I approached.

John Potter: My association with Centrepoint isn’t secret. It’s never going to be secret. [Sexual abuse] was such a tiny part of the Centrepoint story. It’s been put out by people who have got an agenda. Most people are pretty sick and tired of it.

Do you meet many who were at Centrepoint?

There actually is still a community in existence. We don’t live here on this property, but there are a lot of connections, and a lot of people still socialise together, go on holidays and do lots of stuff as a group. Younger and older. And when we meet up, immediately there’s some kind of bond. Our house, where we live, has become a little bit of a focal point for various get-togethers.

Do you look back at Centrepoint as a cult?

It’s not the terminology I would use, but there’s certainly quite a lot of cult-like aspects to it. But “cult” is one of those words that has become meaningless. Like “paedophile”, it’s moved so far from its real meaning.

Why was it seen as a “sex cult”?

Bert was doing encounter groups for many years, starting at my family home when I was a teenager. Bert was the kind of person that counsellors would refer women to when they were stuck with their sexuality. His supporters were this bunch of women, and suddenly they’d been opened up and having a wonderful time. That’s what attracted men to come around. I mean, most functional guys don’t actually want to live with an alpha male type who’s giving instructions on every aspect of life. He gave a lesson on how to wipe your bum on the toilet once. But the fact that there were all these wonderful available women around kind of made it worthwhile.

How did Centrepoint develop into a place where, according to a 2010 Massey University study, every third child was sexually abused?

There was the belief that young kids . . . well, that basically you went along with their energy, and encouraged them. Especially in the early days, being sexually open was seen as a really desirable thing. The [adults] who were flamboyant and having sex in the lounge and all that kind of stuff had a certain amount of status. It’s a natural thing to mimic the behaviour of people who are seen as high status.

This is what some of the underage girls did?

They didn’t actually have the maturity to understand the consequences of what they were doing. And so they got treated as adults, basically. That’s what’s hard for people to understand: that idea of a dividing line between adults and children just didn’t exist here in the first few years. The vast majority of abuse would have been in the late 70s, maybe through to about 81, 82. It was really open and obvious.

Why did you give a public apology at your dad’s funeral in 2012?

I’ve apologised in public before. There was a Herald article several years before, and I’ve always . . . I mean, it’s a very complicated story.

Tell me.

A lot of people bash Felicity with the fact that she’s married to me and say that she supports Bert’s teachings. So I’ve always taken every opportunity to say that I’m sorry for what I did, and that I don’t think that sex with children is a good idea, and all that kind of stuff. With the funeral, I realised that people would pay a bit of attention. I also wanted to send a message to the people who feel like they were damaged by this place.

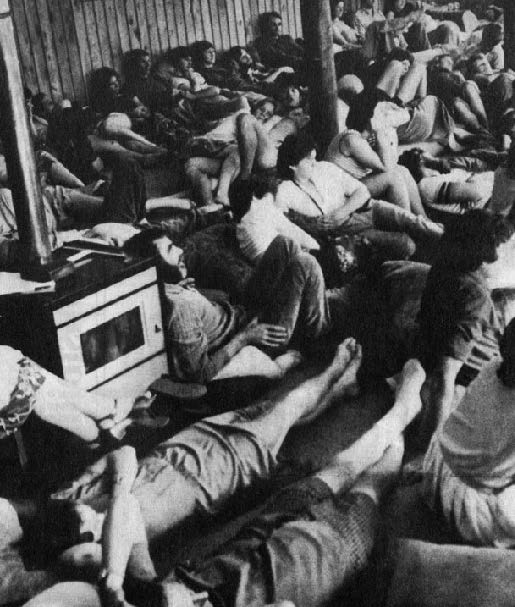

Centrepoint lounge — Bert’s Saturday open meeting. Photo: Supplied

Do you see your actions as “I broke the law” — or, “I broke some girls’ souls”?

“Feel” that they were damaged — or were they damaged?

I’m sure they feel they’re damaged.

Would you also say there are some that are damaged?

Well, I don’t know. I mean, I haven’t had contact with any of them for 30 years.

Have you ever tried to?

That’d be a really dumb thing for me to do. If you’re convicted of a crime like that, you don’t approach victims.

Did you ever consider how to make things right?

Well, I guess all I could do was to make it clear publicly that I don’t support my father’s views in that particular area. Yeah, I just hope that it would perhaps bring some closure for some people . . . not just the complainants in the criminal cases. I did cop a bit of shit for it too, from people who thought I should have been more loyal.

There are still factions — with a lot of hostility.

One group was the Old Believers, who were basically supporting Bert, and then there were obviously the complainants, who wanted the community shut down, seriously trying to get the assets taken over to support victims. There was another sort of reformist group who hoped that they could get rid of Bert as the leader and carry the community on.

Where did you fit in?

I had my own life then and moved on. I was never really a Bert devotee. I came here because he was my dad. In some ways it’s my family home. And it was a neat place to live. I wasn’t seen as a follower by the people in the community because I wanted to do my own thing.

I’ve been told you were copying him to some degree — the prince.

In what way? I mean, I never wanted to be a guru or run a community or anything like that. He certainly had a huge influence on me, and a lot of his values I still hold. In retrospect, that was a really bad mistake. Adults exploring their sexuality should have been separate from having little children around. Maybe there should have been some kind of building where children didn’t go and where adults went to do their thing.

Isn’t there a clear distinction between children just being natural around sex and actively involving them — touching or grooming them, like your father did?

For me now, I wouldn’t have sex in front of my children. In the 70s, that dividing line was moving and it got so blurred here that there wasn’t a line. But I don’t think there was an agenda to go out and have sex with children.

But that’s exactly what Bert and others did.

Well, that’s the media . . .

You’re saying that didn’t happen?

Children do what they see their parents doing. Kids copy adults, that’s just normal.

Kids being sexualised by watching their parents, and then acting that out, is a different scenario to a child being brought to Bert by his wife — or to you, by your partner.

That’s a bit difficult, because all the criminal stuff’s been suppressed. [The name suppression of one of his victims. Louise Winn, was lifted in 2015 at her request.] I’m not going to talk to you about what people were convicted for or what they were charged with.

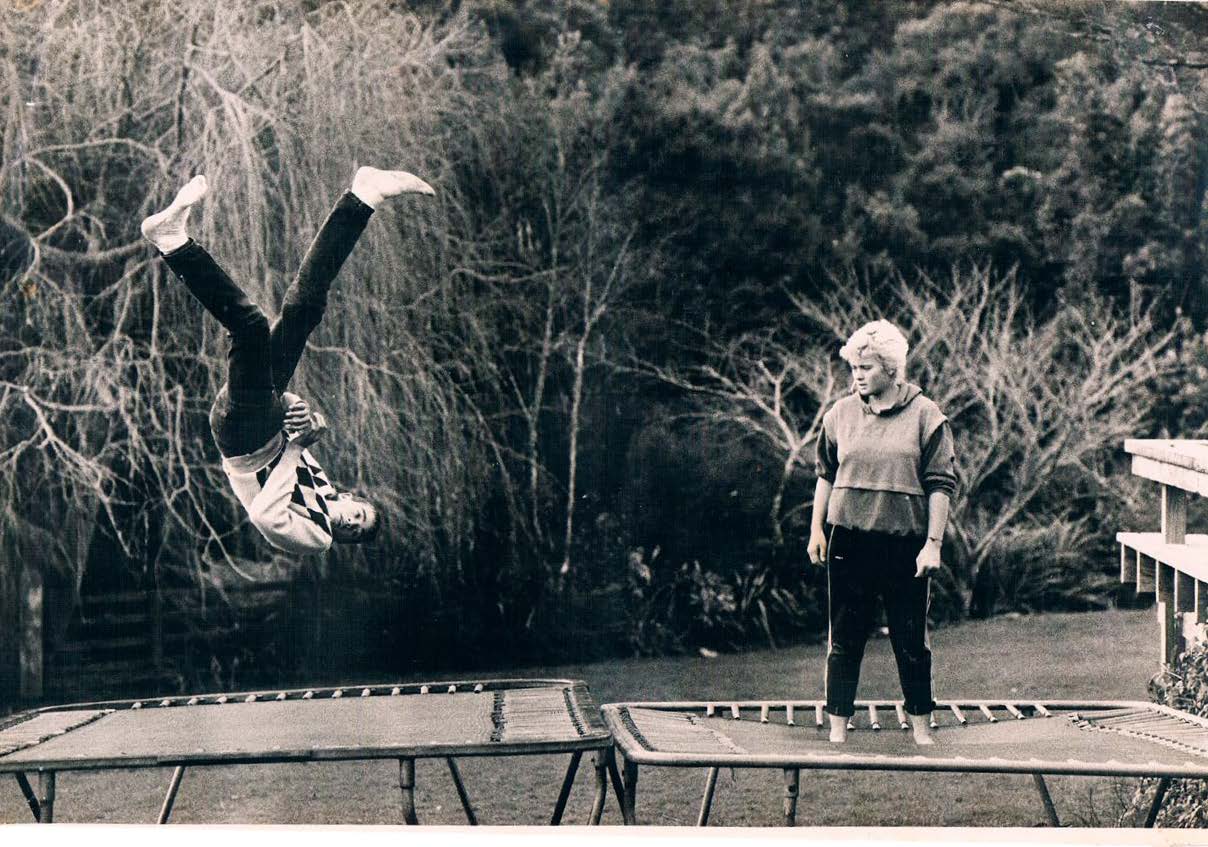

Teenagers at Centrepoint. Photo: Supplied.

I feel bad about it . . . I believed that we were doing something in their interests.

As a birthday present to you, your first wife brought a 12 year old to you for a “threesome”. How do you see it today?

[Very long pause] I don’t think that I can tell you much more. Obviously it was a gift horse that I should have looked in the mouth, and . . . I mean, at the time, I couldn’t believe my luck. In a lot of ways [the girl] would have been higher up the hierarchy than me. She was kind of a leader and a wonderful sexy teenager. I just thought, wow man, I was amazed that she would want to be with me.

She might not have wanted to. This “sexy” role was her survival strategy.

To a certain extent, it was like a reward for me, going with a woman that I really wanted to go with.

You say “woman”. Did you realise that she was legally — and probably emotionally — a child?

I think to be honest I did. I mean, we’re talking about half an hour, it’s not like it was . . . She was physically a woman, and she was beautiful, and there she was under my nose, and naked a lot of the time, like other people were. I saw her as a woman. Even though I only had that fairly short interaction with her, I agree, she wasn’t . . . I mean, when I look back now, I think, how did I get in that situation?

How did you feel when you read her psychological report from her trial?

[Pause] Well, a whole mixture of things. I mean, I knew I was likely to go to jail. It was a pretty tumultuous time. That’s the stupid thing, it wasn’t an important thing for me to have done. It would have been so easy just to say “no, forget it, go away”. And that would have been such a good decision for the rest of my life.

What about Louise Winn, another victim of yours?

I actually don’t remember. I don’t remember anything with her. I’m not saying that at some point I might not have done something inappropriate with her, but it certainly wasn’t enough that it registered on my memory.

She remembers. She took you to court.

Yeah, that was surprising. Because I’ve seen her a few times before I was charged, and she seemed friendly and stuff, and I’ve wracked my brains . . . But having said that, there’s lots of times I did inappropriate things with people under the age of consent.

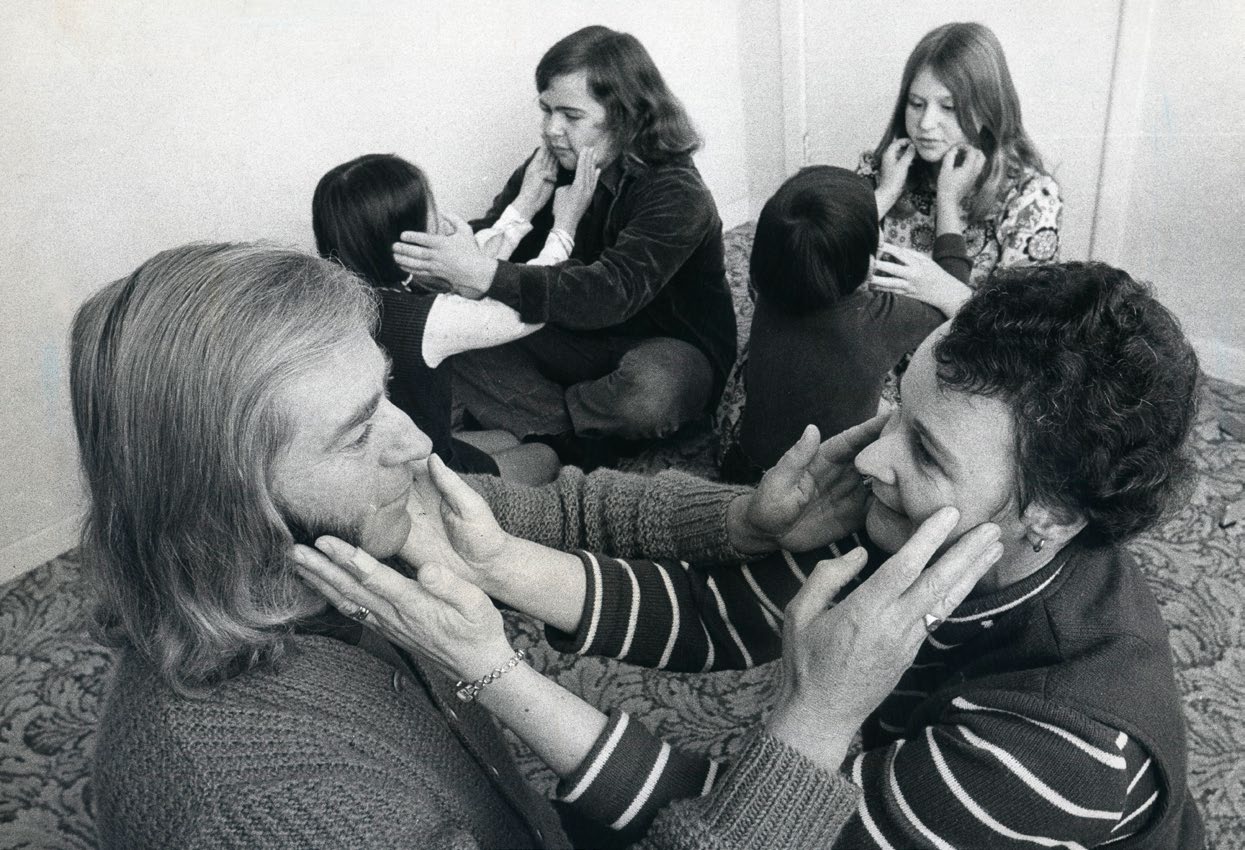

The workshops that took place at the community offered unconventional group therapy. Pictured: Burt in the front with John at the back. Photo: Supplied.

She told me that you had exactly the same routine as your dad every time: clinical oral sex.

I only know about one incident, she only charged me with one. I think she did say she had a threesome. I talked to [my ex-wife] about it. She doesn’t remember anything either.

This sounds like victim blaming. Louise Winn was a pre-pubescent teenager in a predatory cult environment that she hated and couldn’t escape — and brought in by a woman to see you, the son of the leader.

I understand that’s her experience. But as for the details I just have no recollection of it. I pled guilty to both my charges. And that was the end of it. I feel unhappy that she’s out there thinking that I’m some kind of monster. That seems really weird to me.

What made you plead guilty if you can’t actually remember?

There was a whole lot that I didn’t get charged for, so I kind of figured that I broke the law, and I deserved the consequences. I understood that then. One of the things about pleading guilty is that I actually got very little information about what I was accused of. There’s a charge sheet. But that’s just very basic, two lines. I would have gone to jail for quite a lot longer if I defended it.

So you had no trial, unlike Bert Potter and Dave Mendelssohn?

No. The police were going to call witnesses and stuff that I had no depositions for, so we had no idea how to mount a defence, or what they were going to say. I really didn’t actually find out much at all. You’re filling in details now that I’ve never known.

Do you see your actions as “I broke the law” — or, “I broke some girls’ souls”?

That is a little bit hard for me to accept. I mean, if they feel like that, then I guess I am responsible, and I feel bad about it, because my intention was exactly the opposite. I believed that we were doing something in their interests.

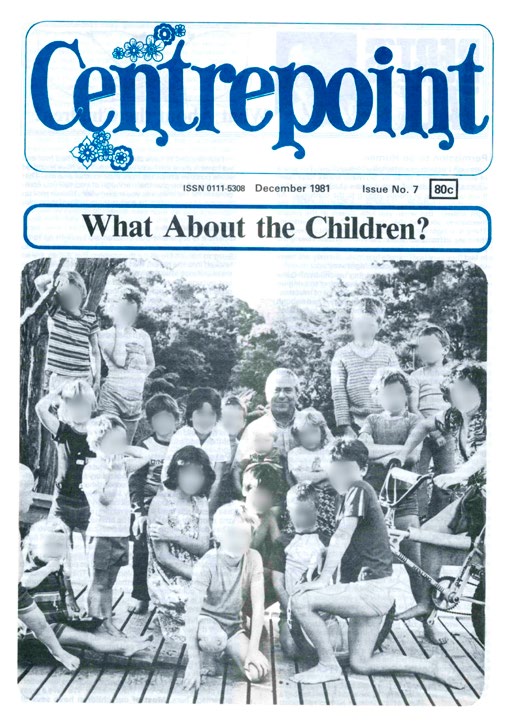

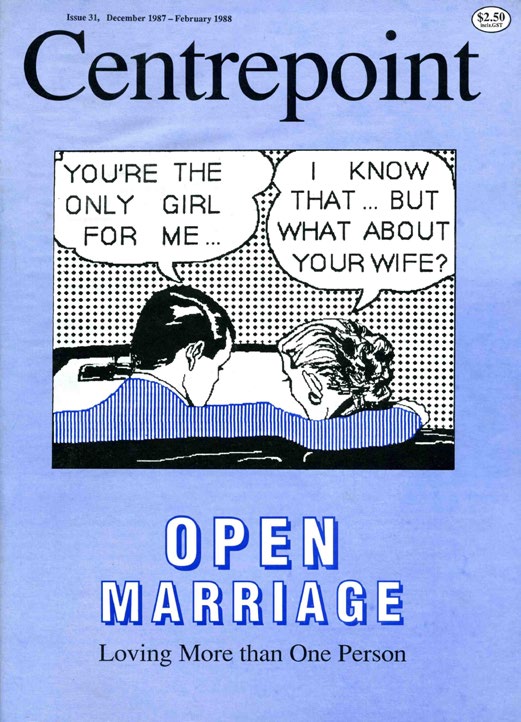

Cover from the commune’s magazine. Face of minors have been obscured. Image: Supplied.

Louise Winn was a manipulated and defenceless child. “Threesome” implies there were three equal and consenting partners.

When I look back on any of the sexual things I had with people who were under age, I saw them as a threesome. I saw them the same way as if I’d been in bed with two adult women.

But she was a child.

Yeah, in retrospect I look back and think, how could I have not realised that, but I didn’t. And I don’t think any of us did. We all thought that that division between children and adults around sexuality was kind of a hang-over from the Christian conservative. We thought that we were at the forefront of the sexual revolution, it was just a matter of time before everybody else caught up. That was the danger of a community where you get isolated from public opinion. When you live in a relatively closed society, “normal” becomes quite different. For anyone who was a child at Centrepoint to go out and find that that’s not normal at all. I can see that it was damaging, and we set them up for that.

You sound like the Old Believers: if the victims hadn’t been exposed to the norms outside of the community later, they would have been fine with their experience?

When I look back from what I know of Louise’s experience, no, it was clearly damaging for her. She was not a happy girl when she lived here.

You were one of the reasons. She tried to kill herself when she was 12.

Yeah, and I guess I am sorry if I contributed to that.

She’s still scared of coming to Albany because she could bump into you.

I find that pretty surprising that I would be such an important part of her life, when I can barely remember. When we were charged, it was quite difficult feeling guilty for something that I didn’t remember doing.

Do you think you were dobbed in while others who were complicit got off lightly?

There were women who blew girls off as well. It wasn’t only guys who did it. Suzanne [Brighouse] went to jail, and Margie [Potter] went to jail. I don’t think it would have particularly done any good by sending more people to jail. But lots of people got away with stuff they could have gone to jail for. I’ve got no idea why the police decided to charge the people they did.

Cover from the commune’s magazine. Face of minors have been obscured. Image: Supplied.

Louise Winn has never had any therapy — she just pushed Centrepoint out of her life. Do you want to add anything?

[Long pause] No, not really. I’m surprised actually, by what you’ve told me, that I figure so importantly. And I feel bad that I did. There wasn’t anything in it for me. I’m not sexually attracted to young girls. I never have been. It’s not something that is part of my reality.

Which means you are not a paedophile?

In the later years, several guys came here because that was their primary attraction. I don’t even believe that Bert was a true paedophile.

Just with a huge sexual appetite, for anything?

Probably. He must have had some interest in the younger girls, but certainly not exclusive. Most paedophiles don’t relate to older women. They’re only really interested in youngsters. None of the guys that were charged fitted that description.

Did you encounter any hatred in prison as a sexual child abuser?

No, I didn’t run into any of that. Partly because I applied to go in the protection wing at Mt Eden, which was where all the Centrepoint guys went. It’s a Victorian, cold stone building, a pretty grim place. Within about an hour of getting there, I saw Bert. [Laughs] There’s my dad! A couple of hours later he actually managed to get the guards to open a few gates, so he could come and give me a hug and catch up, which was really nice and reassuring.

How did he fare inside Mt Eden?

He was working in the prison sewing shop. He convinced them that because of my experience of making belts that I was a machinist and I had skills, so I got a job in there, and Dave [Mendelssohn] was working in there too.

Was Bert Potter trying to get a following in prison too?

He was very popular. Quite a few guys who did time with him said, “He was really supportive to me.” That was the kind of guy he was — actually interested in people.

Was he ever attacked?

There was one incident at Mt Eden when the guards accidentally left him in a yard where there was access to the mainstream prisoners, and someone punched out his two front teeth. He was probably in a lot more danger than me. Any old guy in prison was assumed to be a paedophile.

Bert called himself “God”. Being the guru’s son gave John Potter a high status in the cult. Photo: Supplied.

After Mt Eden, you were at Ohura, an old coal mining camp.

There wasn’t even a fence around it, it was actually quite pleasant. I look back on it as a bit of an adventure, really. We spent our days in the outdoors chopping down trees and cutting up firewood.

You have a nuclear family now. Do you look back at yourself as an absent father in those early years?

Not absent, but neglectful. Basically, because I was interested in women. That was my number one focus. My boys grew up in a gang, they were pretty feral. They probably have a few mixed feelings, but mostly they look back on their childhood as a pretty wonderful adventure.

What about your other victim? From what I know, she’s still very angry.

I’ve sometimes wondered whether [she] would want to have any kind of dialogue. Something really weird happened a few years ago when a whole big bunch of us went to Christmas in the Park. [She] suddenly turned up, I think she had her daughter with her, and she came and sat right next to us. We were sort of thinking, well, what do we do? I felt pretty uncomfortable and vulnerable, to be honest.

Would you like to live in a community again?

A combined financial thing with other people: no. The idea of having to go to a meeting and get an unanimous decision before you can buy a $2 watch battery — I just don’t ever want to go there again.

Do you still live in an open relationship, or have you embraced monogamy like others from Centrepoint?

It’s not something I want to talk about publicly. I have quite a lot of contact with guys who have broken relationships, and I run support groups for men that are trying to get more access to their kids. I see so many relationships that have broken down over one partner or another going off and bonking someone at a party or something like that. What’s the big deal? A lot of people have got such unrealistic expectations of human behaviour.

Is there anything you would say to Bert Potter now if you had the chance?

I’d tell him I’m glad I had him for a dad, even if he did lead me astray.

Anke Richter wrote about Centrepoint for North & South in 2015 and 2018 and is holding a talk at Thistle Hall in Welllington on 18 June.

This story appeared in the July 2021 issue of North & South.