How to Buy a Mountain

With precious pieces of New Zealand at risk of being snapped up by wealthy overseas buyers, Kiwis have increasingly turned to crowdfunding to secure public ownership of the places they love.

By Sally Blundell

The majestic landscape of the proposed Te Ahu Patiki reserve. Photo: Courtesy of Prof. Ekant Veer.

Last October, about a hundred people assembled at a brewpub in Lyttleton to raise some money to buy a mountain. It wasn’t your typical glitzy charity do —more jeans and jandals than black tie, more backpacks than bling. But then it wasn’t your typical fundraiser, either.

The assembled guests had been invited to Eruption Brewing bar for the launch of a crowdfunding campaign to purchase 500 hectares of rugged land about 40 minutes drive from Christchurch. If successful, the new Te Ahu Pātiki reserve would connect private reserves and Department of Conservation land to form a 1700-hectare summit-to-sea network of tracks between Christchurch and Akaroa. It would put Mount Herbert/Te Ahu Pātiki and Mount Bradley, the two highest peaks of the Christchurch/Ōtautahi district, under conservation management; ensure walking tracks currently on private land remain accessible to the public; and return historic pasture lands to native bush.

Lying directly across the harbour from Lyttelton, it is a dramatic landscape. Steep gullies of native bush give way to open pasture and rocky outcrops, kererū ruffle the autumn air, pīwakawaka flit across the lower tracks.

Can it be ours? The Te Ahu Pātiki appeal is the latest of a number of crowdfunding campaigns in recent years asking ordinary New Zealanders to pitch in and buy a block of significant land. The campaigning tactics vary, but the goals are usually the same: to ensure public access, restore natural biodiversity, return land to iwi or stop it being snapped up — and locked down — by foreign owners.

They are plausible goals. After all, each year we give around $1.5 billion in personal donations to charitable organisations. The UK’s Charities Aid Foundation put us in third place in its 2019 World Giving Index — we are also the only country to appear in the top 10 for all three philanthropic measures: helping a stranger, donating money and volunteering time. But giving a few dollars for Daffodil Day or a guide dog is one thing. How do you get Kiwis to fork out for a mountain?

In the case of Te Ahu Pātiki, the price tag was $1.5 million to purchase the property, put a covenant on the land and do the required fencing, track building and maintenance work. The Rod Donald Banks Peninsula Trust, which was driving the campaign, put $600,000 into the pot. (Its fundraising initiatives included selling Christmas cards inscribed with “Gift a mountain to those you love”.) The neighbouring Orton Bradley Park, which would manage and eventually own the land, put in $300,000. That left a still-substantial $600,000.

And this is where the gathering at the bar came in. The venue had been strategically chosen, since it looks straight across the harbour to the jagged skyline of the planned reserve. All going to plan, the wine would be poured, nibbles served and speeches made in time for prospective donors to get a picture-perfect view of Mount Herbert/Te Ahu Pātiki drenched in the rays of the setting sun.

There was just one hitch, says Suky Thompson, manager of the trust: by 7.30pm the dramatic skyline was stubbornly shrouded in a cloak of grey. “The bloody mountain sat in cloud the whole night.”

Images circulated on social media for fundraising appeals for the Wekaweka Valley, Araroa Inlet, Te Ahu Pātiki and a block of ancestral Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia land in the Wairarapa.

The history of online crowdfunding land for public ownership in New Zealand begins with a small lip of golden sand and native bush. Familiar to walkers on the Abel Tasman Coast Track — at low-tide trampers can detour from the inland track to cut across the estuary — the beach on Awaroa Inlet was bought in 2008 by Wellington businessman Michael Spackman for $1.9 million. In 2015, with Spackman facing a multimillion debt claim, it was back on the market.

On Christmas Day that year, Christchurch brothers-in-law Duane Major and Adam Gard’ner — both 43, both self-described blue-sky thinkers ‘ stepped outside the kitchen hustle and bustle for a natter. Major is a senior Baptist pastor and youth worker (favourite movie: The Castle). Gard’ner, then a tennis professional and coach developer, now works with Sports Canterbury as an advocate for physical activity. Two practical family men with a love for the outdoors. They were shooting the breeze about holidays, house prices, and the possible replacement for Crusaders coach Todd Blackadder when the conversation turned to Awaroa — a favourite camping ground since they started taking their young families to the remote beach. The idea that the place where Major first taught his children to kayak could be bought by a foreign owner was especially galling to them. Their fears were not unfounded ! between January 2013 and December 2014 the Overseas Investment Office had approved the sale of 250,000 gross hectares of land to overseas buyers. (“Gross hectares” includes land bought by joint NZ-overseas ventures; between January 2018 and December 2019 this figure was 270,000 hectares).

“I said, that is so dumb,” recalls Major. The two men started musing over whether it would be possible to buy the land themselves. They estimated the sale figure would be somewhere in the ballpark of $2 million. “Adam said he’d put a thousand bucks in, I said I’d put a thousand bucks in. All we’d need is another 2000 people.”

Neither man had any experience of fundraising. But as a board trustee at his children’s primary school, Major knew what a community could do when it put its back to a shared goal. “We have built playgrounds, rebuilt the pool, we have a hangi for 100 people every year. You multiply that community spirit times the population of New Zealand and I was convinced we could do it.”

On 22 January, in the middle of the summer school holidays, they pushed “go”. By the end of the second day, only three people had given to the cause. Two of them were Major and Gard’ner. Then there was an interview on the radio, says Major, “and it just went ballistic”. For three weeks they worked 12-hour days on the appeal, labouring over social media posts, giving regular updates (including over 40 on the Givealittle page) and explaining in interviews why we should cough up for a small bay with no road access that many of us would never visit.

“Adam said he’d put a thousand bucks in, I said I’d put a thousand bucks in. All we’d need is another 2000 people.”

“We did get a lot of tough questions,” says Major. “Is DoC trustworthy? Is it at risk of being influenced by the government of the day? What about sea-level rising? Aren’t there more biodiversity places we could take an interest in? If we have only a small amount of money, is this the best spot? We said this is worth the same as a three-bedroom house in Auckland, so it’s not a lot, actually.”

By the time the pledge period closed three weeks later, over 39,000 Kiwis had stumped up $2.2 million. It was a huge sum, but as the tender process dragged on in a painful four-day process of negotiations between lawyers, real estate agents and unidentified prospective buyers, Major and Gard’ner feared they may have been outbid. Although Givealittle had agreed to freeze the tally of donations on the appeal page — preventing other bidders from seeing how much their competitors had — the “People’s Beach” began to seem like a mirage. Fearing the worst, the two men wrote a speech thanking all New Zealand for their help.

Then, the Joyce Fisher Charitable Trust gave $250,000 to the campaign. On 23 February, the Department of Conservation upped its contribution through the Nature Heritage Fund to $350,000. The following morning, live on Paul Henry’s show on TV3, Major and Gard’ner announced their $2.83 million bid had been successful. “It was spine-tingling,” recalls Major. “Really good reality TV.”

The raised funds were put into the newly formed Awaroa Beach Property Trust, with Major and Gard’ner as trustees, then transferred to the vendor. Five months later, following a process drafted by two teams of lawyers working pro bono, the property was taken out of trust ownership and gifted to the Department of Conservation. On 10 July 2016, the 7.3-hectare property officially became part of Abel Tasman National Park. The story won international attention; theses have been written on the campaign for what one calls “a place engraved in the collective memory”.

“Perhaps there was a bit of charm around these brothers-in-law who were also great mates who banded a whole lot of people together,” muses Gard’ner. “But there was also that sense of Kiwidom, that number-8 wire mentality. And we were so careful about our messaging. The line we used was, here is this pristine beach and bush at the heart of the Abel Tasman National Park on the international market — can’t we just all own it for everyone to enjoy? For always? That really rang true for people. We had people saying, ‘I’ll probably never get there but this is really important’. Or, ‘This is for my mokupuna’. Or, ‘This is the last $7 from my pay packet but it is well worth it.’ Regardless of where people have grown up, there is a connection.”

Christchurch Press editor Kamala Hayman and trust chair Maureen McCloy celebrate the success of the Te Ahu Pātiki campaign. Photo: John Kirk-Anderson, Stuff.

Since then, the brothers-in-law have been helping other similar campaigns. In 2017, they lent their support to a bid by the Native Forest Restoration Trust (NFRT) to purchase 112 hectares of native bush in the Wekaweka Valley near Waipoua Forest. Close to the legendary Tāne Mahuta, the land had been offered to the trust at a reasonable price by a group of local property owners on the condition the purchase would be completed quickly. For over 40 years, the NFRT has been supported by benefactors, volunteers, landowners and other organisations to help buy and protect ecologically important land. It manages over 30 QEII covenant-protected reserves covering 7000 hectares of native forest and wetlands. Using the Trust’s website and the Givealittle platform, the Wekeweka appeal reached the required $185,000 in just a couple of months.

But some kinds of land apparently have a greater hold on our popular affections than others. In 2018, American billionaire Ken Dart, who is based in the Cayman Islands, put Lilydale Station in South Canterbury on the market. Christchurch conservationist and artist John Overton feared that Lilydale, a 4046-hectare high country farm, would be snapped up by another foreign buyer with little interest in allowing New Zealanders to access any part of the land. Inspired by the beach campaign, and with some advice from Major and Gard’ner, he launched a crowdfunding appeal for $3.5 million to buy the station for New Zealand. The land, home to the Fox Peak ski area, would have effectively bridged the two arms of the Te Kahui Kaupeka Conservation Park, which includes part of the Te Araroa walking trail and portions of Samuel Butler’s Mesopotamia Station.

The station was mainly accessible only to hardy trampers, climbers and skiers, and the campaign did not have the backing of influential organisations such as Forest & Bird and the Federated Mountain Clubs (FMC) or the government. “At the time, there were higher priorities with land that contained more threatened ecosystems,” says a DoC spokesperson.

In the Wekaweka Valley, for instance, the extraordinary flora and fauna, including the North Island brown kiwi, were at risk of pests and predators. Lilydale, by contrast, was relatively secure. “It is the highest piece of freehold in the country, it is outstanding landscape but you can’t run stock on it, and you have public access in winter anyway because people go there for the ski field,” says Peter Wilson, president of the FMC at the time. “I think a lot of people saw that Fox Peak basically protected itself.”

On 21 August, 13 days after launching the appeal, and with only $9,416.00 pledged, Overton ended the campaign. Lilydale has since been sold to New Zealand farmers and conservationists Warrick and Wendy Day of Te Anau.

Duane Major and Adam Gard’ner lent their support to a campaign for land in Wekaweka Valley. Photo: Supplied.

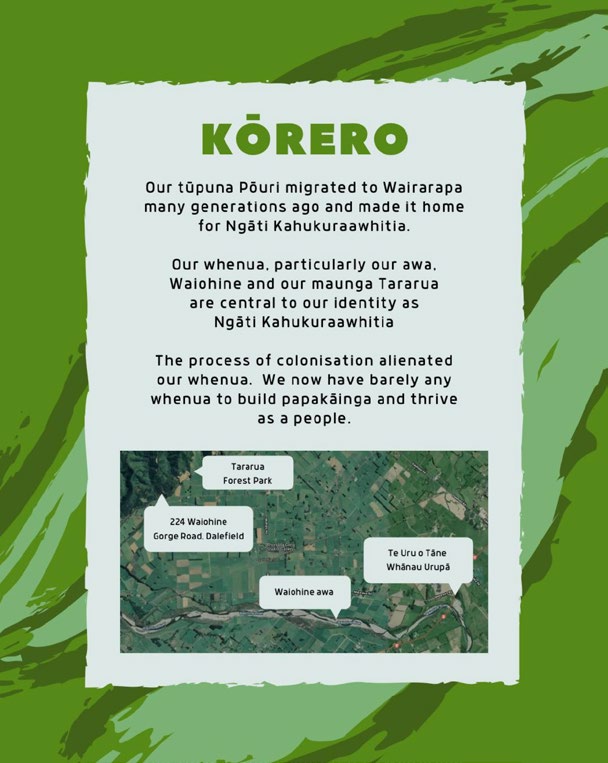

The opportunity represented by the crowdfunding trend has also been recognised by iwi. This year, representatives of a Wairarapa hapu attempted to buy 182 hectares of ancestral Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia land in the foothills of the Tararua Ranges. The land, including 157 hectares of native bush, was advertised by PGG Wrightson Real Estate as a “piece of paradise with multiple income opportunities from forestry, bees, firewood, lodges, ecotourism”.

With a tender price of $1.2–1.5 million, this was always going to be a challenge for a hapu without a strong financial base. The settlement of the Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa Tāmaki nui-a-Rua Treaty claim, of which Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia is a part, has yet to be completed. Business bank loans for land-based projects, says Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia descendant Amber Craig, tend to be directed to dairy farming, whereas the hapu hoped to use the land for sustainable housing and the manufacture of rongoā, or traditional Māori medicine.

Crowd fundraising was the only option. “We thought, we have nothing to lose,” says Craig. “Worst case, we’d get $10 # that is $10 more than we had yesterday.”

In early April, cousins Craig and Joel Ngātuere launched a Givealittle page seeking $500,000. “You can sit around and just talk about the injustice of the past,” says Ngātuere, “ but if we don’t do anything it just makes it harder for the next generation.” If the tender bid was unsuccessful, donations would be held in a trust that could only be used to buy another parcel of land at a later date.

The campaign was certainly lower key than that for Awaroa Inlet. While comments from donors from around the country and overseas were positive, there were few page updates and the appeal did not seem to draw the same media attention.

By the time the deadline for tenders closed on 13 April, the Givealittle campaign had raised $182,919 on top of around $110,000 of direct donations — well short of the $500,000 target. While PGG Wrightson will not disclose the identity of the buyer, it said the property was sold to a local farmer.

Still, says Craig, the response was “heartwarming”.

“We had some amazingly kind messages. People said their ancestors were original settlers in this area and they thought it was their obligation to give back. Some people had been brought up there and wanted to give back to the whenua. Some people gave their bus pass money.”

While their bid was unsuccessful, it may have inspired others. In May, Waikato hapu Ngāti Tamainupō launched a Givealittle appeal for $1 million to help buy an historic garden site, currently earmarked for a housing development, in Ngāruawahia. Unlike the Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia appeal, this is an “all-or-nothing” campaign — if the target is not reached within six months, all donations will be returned.

Left — A campaign to purchase a block of Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia ancestral land at the foot of the Tararua Ranges was unable to raise sufficient funds. Photo: Meriana Johnsen, RNZ. / Right — Amber Craig, a member of the Ngāti Kahukuraawhitia hapu. Photo: Courtesy of Rahiri Makuini Edwards-Hammond.

Despite the cloudy fundraiser for the two mountain peaks of the proposed Te Ahu Pātiki reserve, the Canterbury campaign seemed to hit a nerve. Within 24 hours, says Thompson, the organisers received a $100,000 donation from a “lovely couple” who asked to remain anonymous. “That came completely out of the blue,” she says. “We have had other really generous donations but if you take that one out the mountain is a little harder to climb. It takes a lot of $50 donations to get to what you want to raise.” By mid-May, the Trust only needed another $144,000.

Like the Native Forest Restoration Trust, the Rod Donald Banks Peninsula Trust is a registered charity with a sound record of environmental management. Formed in 2010, it has been working with DoC for eight years to complete the Te Ara Pātaka walkway, a network of tracks across the ridgeline of Banks Peninsula. Most of the land belonged to DoC or is legal road, but eight kilometres of tracks crossed Philip King and Sarah Lovell-Smith’s historic Loudon Farm. After the walkway opened in 2016, the trust approached the couple to discuss ways of securing permanent public access to those tracks. The landowners turned the tables and suggested the trust buy the land instead.

“It changed from securing public access into a project of buying,” recalls Suky Thompson. “We were up for it.”

With advice from the Christchurch Foundation, their primary fundraising platform, the trust made a video, redeveloped its website, put out news releases, posted on Facebook and Instagram and ran ads in local print media. Stuff, which supported the Awaroa campaign, backed the appeal with a donation of $20,000 and a Press cover story. By 2.30 pm that day, a month before the campaign end-date, they had exceeded their target.

Some kinds of land apparently have a greater hold on our popular affections than others.

For Amy Carter of the Christchurch Foundation, this was not surprising. The Te Atu Pōtiki pitch, she says, is a great visual story. “They are our two taonga, the tallest part of our city.”

It also completes the ambition of tireless hiker and pioneering conservationist Harry Ell, Christchurch MP from 1899 to 1919, whose dream of a walking route between Christchurch and Akaroa eventually lead to the creation of the popular Te Ara Pātaka/Summit Walkway. True to Ell’s progressive goal, the completion of a summit-to-sea park would ensure permanent public access to the hills and gullies of Banks Peninsula and alleviate fears of further development encroaching on the track system.

Celebration was threaded through with relief. After a year and a half of negotiations, the trust had entered an unconditional agreement with King and Lovell- Smith, giving it eight months to raise the required funds before the land is transferred into its ownership on 1 July.

“We got to the point where we felt the best way forward was to take that brave leap and get that unconditional agreement in place,” says Thompson. Still, if the targeted figure of $600,000 had not been reached, the trust would have had to dig deep into its reserves to complete the sale, covenant the land, put in the required fencing and signage and fund ongoing track maintenance work. This could eat into funds earmarked its other essential work.

Donors tended to have an interest in conservation and tramping and a strong connection to the local landscape. “They know Mount Herbert and Mount Bradley, they look at them from their houses or from the Port Hills or they went hiking up these hills when they were young,” says Thompson. Uprising, a new gym, yoga and climbing studio in Christchurch, offered to match contributions up to a total of $10,000. The offer raised six grand $ they gave 10 anyway. “As a young business we really should be paying down debt,” says co-director Sefton Priestley, “but the area really resonates with a lot of people around Canterbury. This is an amazing, majestic place.”

Seven months after the campaign launch, Thompson looks out over that skyline from the verandah of the historic Ōtotomiro Hotel in Governors Bay. The sky is clear, the mountain tawny in the late afternoon light. Come July, they will have completed negotiations with the neighbouring Orton Bradley Park Trust and mana whenua Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke in regard to future ownership and management. Work will be underway to improve tracks, withdraw most of the stock, eradicate pests, control weeds and put in fencing. They will also be planting native trees (to help cover costs, the trust is part of a group lobbying the government to make it easier for naturally regenerating native forest to qualify for carbon credits). But for the most part, this dramatic saddle of land will be left to revert naturally from pasture to publicly accessible native forest funded by the people of New Zealand.

“It is about letting people know there is an opportunity to contribute,” says Thompson. “To feel in your heart you have been part of protecting something and to be able to walk there with your children and grandchildren and say, ‘You know what, kids — we helped to make this happen.’”

Sally Blundell is a journalist in Otautahi Christchurch.

This story appeared in the July 2021 issue of North & South.