Culture Etc.

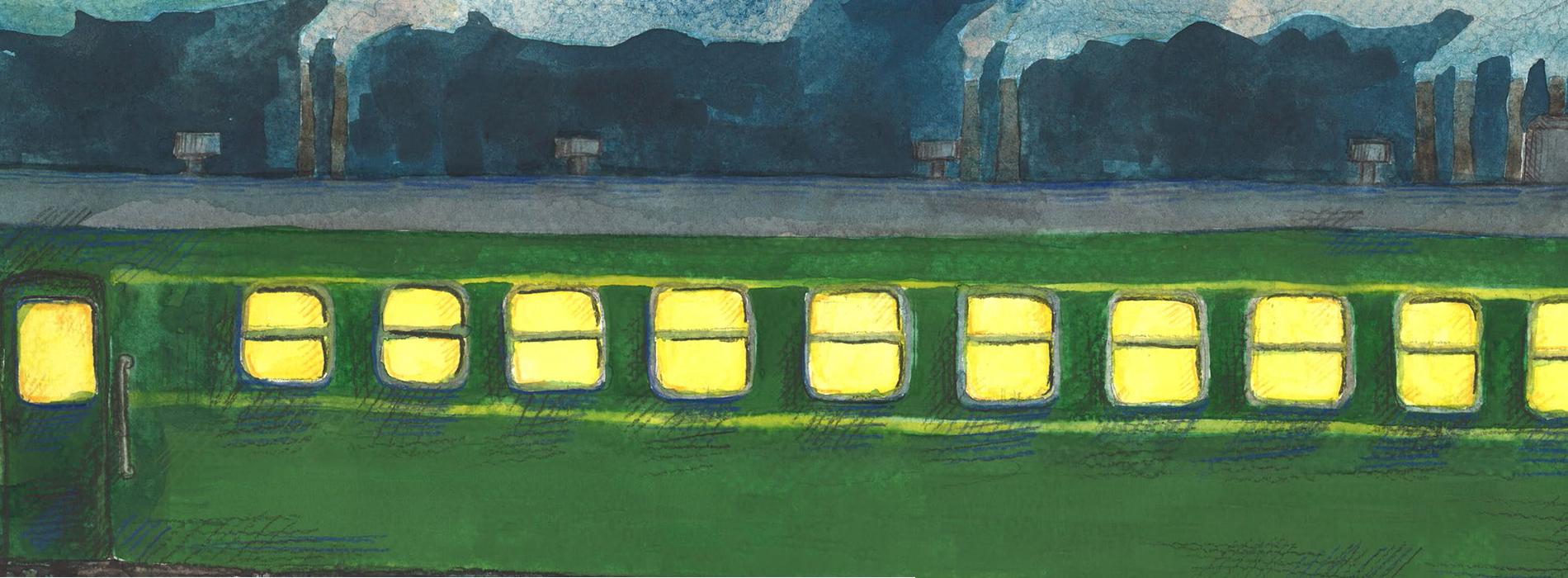

Above illustration: Imogen Greenfield

Hard Sleep

On a night train, even a disillusioned traveller can sleep like a baby, cocooned from the raucous real world that awaits at their journey’s end, and still feel just a little intrepid.

By John Summers

Many, many mornings, I try for a sleep on the train. This I attempt as the track rises towards the darkness of the Remutaka tunnel. I stretch out my legs, arrange my arms loosely in my lap. The seats have slight wings which cup my head just enough that it slightly rocks with the rattle of steel wheels on steel rails. Eyes closed, I listen to the clack of those wheels, the snuffy whistle of others sleeping around me and, more often than not, I remain wide awake. Sometimes though, just sometimes, I emerge from the tunnel asleep, and midway through the Hutt Valley I wake up, feeling close to drowned. This sleep, too brief to provide any refreshment, leaves me half awake and wanting back into snoozeville for the rest of the day. I struggle on, foggy and unable to hold a thought, cowering from small talk, from all talk really. In this way, that brief nap on the train is the best predictor I have of a bad day, and yet I never stop attempting it, craving train sleep, the best I have discovered. Sleep is sleep, you may think, but you’d be wrong. There is something luxurious about giving in to heavy eyes, letting slumber wash over you, all the while carried along, the wheels beneath blurring to clouds, a moving cushion, blissfully zonked and completely in the care of KiwiRail.

This phenomenon I first discovered in China, and have repeated in other countries since, drawn to those two magic words: night train. I can report that of them all, the Spanish were the most luxe, offering a four-bunk cabin and a plastic-wrapped toothbrush. In America, Amtrak was good if expensive, and they fed us silly.

The Russian trains we took were of the Soviet era, filled with young men returning from military service — they wore the most swashbuckling uniform: dark jackets over Breton shirts, and beribboned hats, and these outfits matched the theatrical returns they made to their hometowns, stepping down with arms outstretched, kissing the air, as babushkas and girlfriends swooned. But between stops, they sat quietly. We all shared the open space of a third-class carriage, ingeniously filled with bunks and seats that folded into beds and, again, I slept well. A few of those men got drunk, and one had to be carried to the toilets, but they did so silently, solemnly really. There was a respect for the sanctity of a good night’s snooze on the train.

But it was in China that I have spent the most time asleep on wheels. Alisa and I lived there for almost a year, in a city called Nanchang. We were English teachers at a university, living and working in a collection of seamy concrete buildings behind a lily pond. Teaching came with long holidays, and we spent these travelling by train to other provinces. We went to Hunan, from where Chairman Mao hailed, and to Beijing, where he lay, a pale-pink mummy in a glass coffin. We went to Sichuan to eat food that made us sweat, to subtropical Yunnan, and dirt-poor Henan.

I never stop attempting it, craving train sleep, the best I have discovered.

China is a communist country but class is everywhere, and its trains offered several types of seat and berth, each a slight graduation from the next in status and comfort. We most commonly travelled in something known as “hard sleep”. A misnomer, it refers to bunks of three, not hard at all, all facing another set of three. There is a partition between each set of bunks but it was an open space so you could wander past the sleepers. This equated to second class. First was known as “soft sleep”, the bunks not actually softer but limited to four, within an actual room that contained a thermos of hot water and a doily. Still, hard sleep was comfortable enough, capable of inducing that incredible blissful sleep. I lay wrapped in China Railway’s clean and starchy sheets. The non-stop of wheels on rails, a universal language, translated through springs and the frame of a bunk bolted to the cabin wall to a gentle rocking, the sensation of floating, cocooned and carried on through the night, out of it for hours and dreaming pleasant, unmemorable dreams.

Our living in China was itself the extension of a dream. In the years leading up to our trip, I had read stories in the news about China as some sort of frontier, a place where people went into business and found new callings. The country’s growing middle class were keen for things we took for granted, whether it was milk or English lessons, and it meant there were opportunities for the mediocre. I saw myself as a new version of the old China hand, falling backwards into some job more exciting than teaching. These were the musings of someone drunk on privilege, something helped along by the ease with which I’d got a job there, and bolstered too, I think, by years of reading travel writing. It is a form I love, but it is also one reliant more often than not on a shaky premise: the notion that being in some remote place, backed maybe with a little research and nosiness, will give a literate Westerner something interesting to say. I devoured books of this kind on China. I read very little written by an actual Chinese person. Absurd, I see now, and absurd too to think that in a country of more than a billion I would have something unique to offer.

On the Trans-Siberian Railway. Photo: John Summers.

Still, it would take arrival for this to be helpfully knocked out of my system. I found no other job. In fact, I was barely needed at the one I did. I stood before 40 bored 20-somethings, my lessons in competition with their conversations, phones or need of a nap. There it was clearer why I had so easily won the role: I was a box ticked. The university could now say they had a number of native-speaking teachers on staff, and the content of my classes was barely of any interest to either my pupils or employers. The minute I turned to the blackboard, I heard the jangle of video games beginning, a dozen conversations resuming. Oh well, at least I wasn’t as bad as the poor drudge who taught Marxism. Occasionally I’d peer through the glass door to see him sitting at his desk with a microphone clamped to his face — a dismal karaoke, not noticing, not caring that almost every student sat slumped, their heads down, sleeping as soundly as I did on the train.Simply leaving our two-room teacher’s apartment and walking in the streets was enough to show me how wrong my daydreams had been. What I saw was a humdrum industrial city, packed with people busy getting on without me. Taking a bus into the centre meant elbowing and pushing — no one formed a queue, and once at the centre I had nowhere to go anyway. There were restaurants and a McDonald’s, a museum about the People’s Liberation Army where every caption was in Chinese, and street after street of shuttered buildings, offices in which the work that people did would always be a mystery to me.

It was on the train that I found myself somewhere closer to the China I had imagined. The problems of getting to and fro, of ordering food, of pushing to the front had all been removed, and all I had to do was simply sit and wait and sleep. Outside the countryside rolled past. We stopped in towns that made me shudder: ash-grey, dripping cities bristling with smokestacks. And then we moved on. Once, travelling with another English teacher, I made some remark about getting off to buy a snack in one of these places and then lingering just that second too long so that you’d turn to see the train rushing on without you. Neither of us spoke enough Chinese to get ourselves out of that situation. We’d have to get jobs, I joked, settle down for a while till you earned enough and figured out how to leave.

“You’d be stuck in this Podunk place,” he said, and I chuckled at this new word, “Podunk”, without twigging to the irony: he and I were already doing just what I’d described — stuck in some place, trying to earn enough to leave. It was what we’d done before China, too, working away and all the while thinking about somewhere else. But the whistle blew, the train moved on, kept moving, day and night chugging by too fast for such self-reflection.

Fenghuang in Hunan Province. Photo: John Summers.

This was travelling. I was a traveller. The small protocols of the train — the hot-water heater for instant noodles, the queue for the sink — were easily mastered, restoring my belief in myself as intrepid. Those shared spaces meant having the sort of brief and colourful interactions that travellers crave. On one trip, an elderly man insisted on shaking my hands and declaring, in Mandarin, that he and I were friends. He returned again and again to do this, until his wife yelled at him to get back to his seat. On another, a man boarded with a yoke across his shoulders. A plastic container hung from each side. They were similar to the tanks on top of a water cooler, and each was completely filled with eggs. How had he got them in there? I would never know. That night, lying in the bunk opposite mine, he held a phone to his face and whispered loudly in Mandarin: “I love you. I love you. I love you.” The gentle rattle of the rails worked their magic. I fell asleep to the pleasant chant of this egg man.

Eventually even the longest trip would have to come to an end. The train would arrive at the station, the brakes would give off their burnt smell, and we’d need to pick up our bags and carry them away. In China, this often meant a dark tunnel through the bowels of a huge train station, and as we approached the end of that tunnel we would begin to hear the noise of the city outside. The train had been quiet, people murmuring to each other, and now this was raucous, the yelling of the men who touted for taxis and hotels. They clamoured to get to those weary passengers and, as soon as they saw us, they would swarm. I hated it. Hated the obligatory haggling, the need to start figuring things out, deciding where to go and what to eat, always reaching into my wallet, always feeling lost. My consolation was that in a few days I’d be back to board a train, that I’d hurry to a carriage where I could sleep secure, passing through a world in which people worried and worked and died, and all I needed to do was close my eyes and keep moving, carrying on through and apart from it all, a traveller, a time traveller, becoming for a time a child again, asleep in an adult’s world.

Edited extract from The Commercial Hotel, published by Victoria University Press. The Commercial Hotel is available in book stores now.

John Summers is a contributing writer and editor for North & South.

This story appeared in the September 2021 issue of North & South.