Four Corners

WELLINGTON

The City That Convicts Built

A tour of Wellington landmarks made by prison labour.

Te Aro School sits on a slight rise, to the northwest of central Wellington. From its grounds, Jared Davidson peers through a wire fence at the city below, a jumble of villas and apartment blocks and the Grand Mercure hotel — currently in use as an MIQ facility. But there’s something more that he can see, a scene from the 19th century. You can imagine the chain gangs that once trudged through the streets to work, he says.

A lean and energetic 37-year-old with four books behind him, Davidson is now researching a history of prison labour in 19th- and early 20th-century New Zealand. Research has meant a lot of time spent in libraries and archives (Davidson’s natural habitat; he is an archivist by day), but his subject is everywhere. Although New Zealand never imported convicts en masse like Australia, prisoners were once roped in to level land, build roads and assist with other infrastructure. Sometimes they were even made to build prisons. They left their mark in the shape of our cities, and on this dull spring Sunday, Davidson has left his Lower Hutt home to find evidence of their work in Wellington.

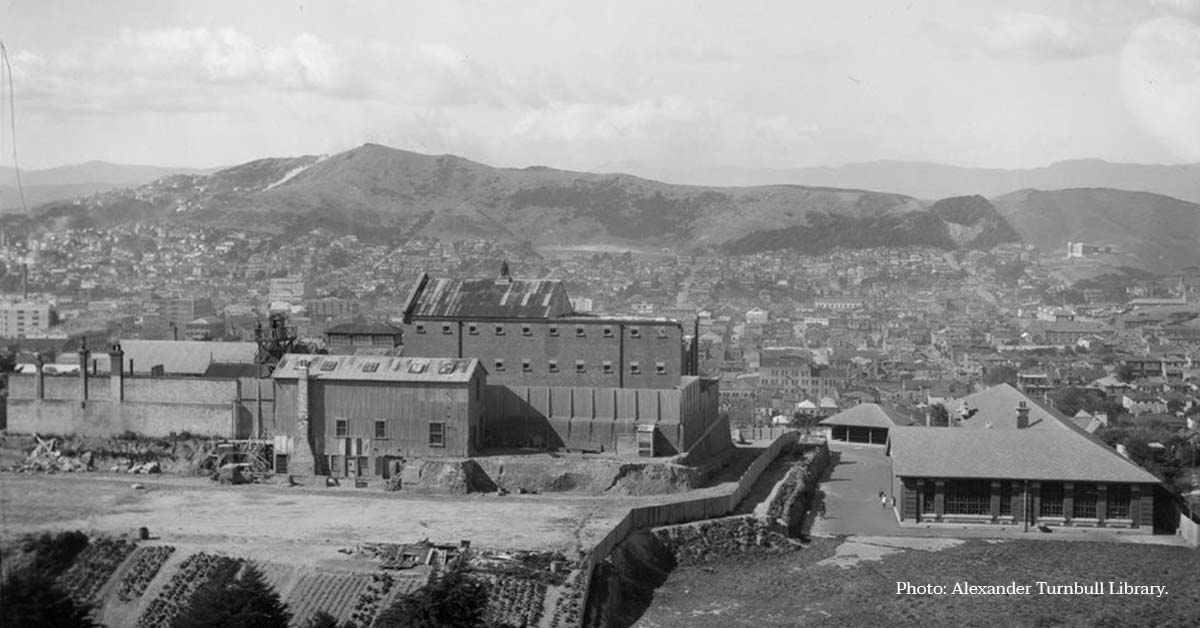

Te Aro School is his first stop, and where he plans to start the book. A typical New Zealand primary school of weatherboard classrooms on a large concrete pad, it is on a site made flat by convicts, who then built a prison there, the infamous Terrace Gaol. Wandering the playground, Davidson describes a day in the life of an inmate. “They would wake up about 7am, have 30 minutes to clean themselves, get a feed, listen to what the gaoler had to say and then they were marched out down into the city to build all the streets around here. The worst prisoners, the guys who had been playing up, would be in heavy chains.” These chain gangs were a visible presence in Wellington well into the 20th century, building roads, drains and retaining walls. Finally, when the prison was no longer needed, it was prisoners who demolished it.

“I start my book with this guy called Harry Brown. He’s a returned serviceman, he fought in World War I, and was a labourer. He was arrested for vagrancy, sent up here for a three-month stint. And as he’s pulling down the bricks and filling in the gullies to make way for this school, the side of the hill collapses on him and he’s killed.”

Leaving, Davidson takes a last look around. It is almost 100 years since that demolition and the building of the school. Two young men bounce a basketball in the space between classrooms. “Under these playgrounds is the clay that smothered Harry Brown,” Davidson says.

The Salvation Army facility on Rotoroa Island. Photo: Salvation Army.

Davidson came to this topic while researching an earlier book and finding repeated references to vagrancy. “There was a real labour shortage on the so-called colonial frontier and wasted labour was seen as the ultimate crime,” he says. Putting prisoners to work in the streets of New Zealand cities also solved another problem, he says — the poor condition of gaols at the time. “Gaol cells were the size of a modern bathroom and groups of men and the odd woman were just thrown in. So it made sense to get them out of there during the day.” The use of convict labour is almost as old as Pakeha settlement. Davidson plans to include in his book the stories of missionaries like Samuel Marsden who brought English convicts with them in the early 1800s to build shelter and make goods for trade with Maori. “I’m mainly focused on the 19th century because I’m really interested in how prisoners were important to the colonial infrastructure that we take for granted.”

He sees this convict connection in one of Wellington’s most beloved landmarks. Driving past the Basin Reserve cricket ground he discusses its former life as a lagoon, connected by a stream to the harbour. The earthquake of 1855 changed that, lifting the ground and turning it into swamp. It was prisoners who did the hard and dirty work of draining the swamp and levelling the ground, so Wellingtonians could have a cricket pitch. “It was really grubby, muddy work. One prisoner hid out in the flax and managed to make a clean getaway out of the colony, and was never caught again.”

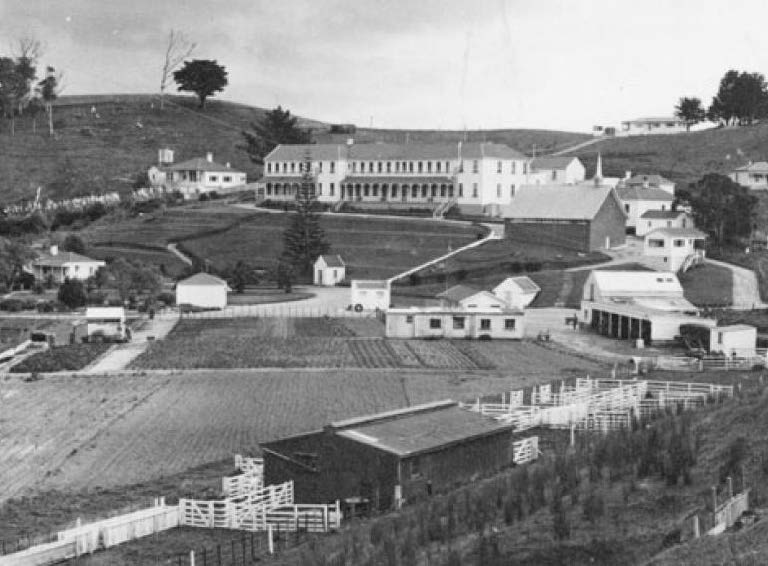

In nearby Mt Cook, he finds another area quite literally shaped by convicts. There they flattened out a space now occupied by another school. They built a prison to replace the Terrace Gaol, and made bricks from the clay of Mt Cook itself, enough to eventually level it by 25 metres, he says. For the most part, this is the way these prisoners made their mark on the city, reshaping a rugged landscape into what we have now.

Walking by the site of those old brickworks, Davidson is excited to see something even more tangible: a brick. Along Tasman Street is a retaining wall of orange bricks, and each is stamped with the same broad arrow symbol that once patterned convict uniforms, a sign that they were made in the prisoners’ kiln.

“Apparently these bricks were of a really high quality and were really sought after,” Davidson says, inspecting them closely. “I think I’ll have my author photo by this wall.”

Detail of Tasman Street brick wall.

By John Summers