Waiting for a Miracle

New Zealand has no Catholic saints — yet. But we have our first best shot: Suzanne Aubert.

By Oliver Lewis

The men, and they are almost all men, are bundled up against the cold. Winter in Wellington can be brutal, and this morning is no exception: grey and drizzling with rain. At the Suzanne Aubert Compassion Centre & Soup Kitchen on Tory Street, staff and volunteers are busy preparing breakfast. For the homeless, sleeping out would have been miserable. “It’s cold as Judith Collins’ heart out there,” one of the men quips. But the soup — carrot and coconut cream — is hot and the atmosphere is warm and collegial. Each table is decorated with a vase of flowers, gathered weekly by the same two volunteers, a woman in her 80s and her daughter. From the kitchen, you can hear someone playing piano: “Für Elise” and then, appropriately, “When the Saints Go Marching In”. She isn’t one yet, but the late Suzanne Aubert, a diminutive Frenchwoman who founded the kitchen in 1901, is on track to become our first Catholic saint. For the 450,000-odd Catholics in New Zealand, this is a very, very big deal.

For the faithful, a saint is someone who personifies Christian values. In old oil paintings, they’re the bearded men and beatific women looking down at you with loving eyes. Because it’s such a high honour, church authorities in Rome are extremely judicious with their selections: potential saints need to have either died for the faith as martyrs or lived lives of exemplary virtue; in most cases, their supporters also need to provide proof of at least two posthumous miracles. Aubert has been dead for 95 years and the case for her canonisation, being advanced by local supporters, is still grinding its way through the arcane process, a multi-step marathon that can take centuries. (An analysis by Pew Research Centre put the average time between death and canonisation at 181 years since 1588.) Historically, people and local authorities created their own saints on the basis of popular demand, resulting in dubious outcomes such as Saint Guinefort, a dog who lived near Lyon in France who was venerated locally for several centuries in defiance of repeated prohibitions from Rome. Wanting to assert some quality control, the church issued a series of decrees in the 12th and 13th centuries specifying a pope, and only a pope, had the authority to make someone a saint. That remains the case, although the real work is carried out by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, a part of the sprawling Vatican bureaucracy nicknamed “the saint factory”.

Like factory work, saint-making is a prescribed process. After a holy person dies, supporters have to wait at least five years before starting a bid for sainthood, known as a cause. Once the coolingoff period ends, the local bishop orders an inquiry into the person’s life to see if they were sufficiently holy, including interviewing witnesses, unearthing documents and examining the person’s deeds. If there’s enough evidence, the bishop asks the Congregation for the Causes of Saints to examine the case. If they deem it worthy, the candidate gets to be called a “servant of god”. In the next step, a postulator — the person charged with guiding the cause through the required hurdles — gathers together the available evidence, including witness testimonies from the earlier inquiry and the person’s writings, into an exhaustive summary called a positio. Historians and theologians in Rome scrutinise the work to make sure it’s factual, asking questions about the local historical context and checking the person didn’t commit acts of heresy. Then it goes to the Congregation and, ultimately, the pope for sign-off. Once that’s been given, the candidate is called “venerable”. Then come the miracles. Most New Zealanders would be sceptical, but the faithful believe that the holy dead, being in heaven, can lend weight to their prayers for help and intercede with God on their behalf. If they do that once, and it’s confirmed, the candidate for sainthood is known as “blessed”, meaning they’re in a state of bliss. To become a saint, you need a second confirmed miracle. (Martyrs only require one.) For each miraculous act, officials comb through the available evidence, including doctor’s notes, medical scans and witness testimonies. Local specialists and a panel of medical experts in Rome analyse the evidence. Each miracle goes back to the Congregation and the pope for consideration and approval.

There are more than 10,000 Catholic saints by some counts. But canonisations are few and far between in the Antipodes. Oceania didn’t get its first saint, Peter Chanel, until 1954. The French missionary was hacked to death on the island of Futuna in 1841; one of his bones, a holy relic, made it to Christchurch where it was ground up and installed in the altar of the now demolished Catholic cathedral. In their famous song, local punks Blam Blam Blam sang about there being “no depression in New Zealand”; in much the same way, Aotearoa has no saints. Holy people exist — they just haven’t been recognised by Rome. At least, not yet.

When Suzanne Aubert died in 1926, aged 91, the streets of Wellington ground to a halt as thousands of people gathered for her funeral.

Mourners pack the streets for Suzanne Aubert’s funeral. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

When Suzanne Aubert died in 1926, aged 91, the streets of Wellington ground to a halt as thousands of people gathered for her funeral. It was, reputedly, the largest service ever held for a woman in New Zealand. Traffic was stopped between St Mary’s of the Angels and the graveyard at Karori and about 90 cars trailed the hearse. Ninety years later, in 2016, Pope Francis declared Aubert venerable, meaning she lived a life of heroic virtue.

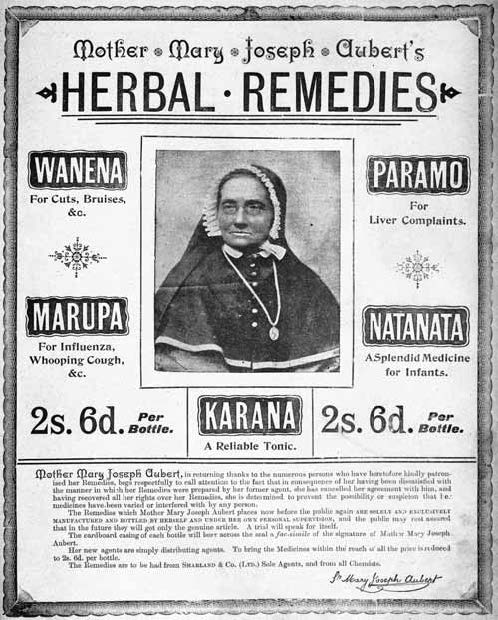

During her time in Aotearoa, Aubert was an unrelenting champion for the poor, the sick and the disabled. The indomitable nun was a short, pragmatic woman who would walk for miles across rugged country and ford rivers to visit remote communities with pocketfuls of bread and cheese. She arrived from France in 1860 on a whaling boat, the 19th-century version of a cheap airfare, with Bishop Pompallier, New Zealand’s first Catholic bishop. Aubert was a young woman of 25, unmarried and determined to pursue a missionary life in defiance of her parents’ wishes. When she arrived in Auckland, a Maori hand was the first hand held out to her in greeting, she wrote in a 1916 letter. Aubert was known as a committed friend to Maori, helping provide education and medical assistance in remote North Island communities. Known as Meri Hōhepa, the young nun — a highly educated, intelligent woman — became fluent in te reo and published one of the most influential early phrasebooks. She also drew on traditional Māori knowledge to develop herbal medicines and remedies. On the Whanganui River, Aubert established the Sisters of Compassion, a homegrown Catholic religious congregation. When they moved to Wellington, she and the sisters founded the soup kitchen, a créche, a home for incurables, and an orphanage and home for vulnerable children, or foundlings, in Island Bay.

A steadfast, uncompromising woman, Aubert clashed with authorities who opposed or sought to undermine her mission. (After Pompallier returned to France, the new bishop told Aubert she should do the same. Instead, she fought to continue her work among Maori and left Auckland for Hawke’s Bay.) She also displayed a deep affinity with the sick and disabled, a connection born of personal experience. Aubert had grown up near Lyon in a well-to-do bourgeois family. When she was two, Aubert and her brother reportedly chased a piglet on to a frozen pond. The ice broke and Aubert fell into the freezing water, striking rocks below. The accident left her crippled and, for a time, blind (an early biography details the incident in a chapter titled “The Ugliest Little Girl in the World”). Years later, Aubert would reference her early disability while speaking out against eugenics, telling supporters at a Wellington conference that, had their policies been in place when she was young, she wouldn’t be where she was today.

The Compassion Soup Kitchen has fed the hungry for 120 years. When it was first set up on Buckle Street, the sound of the sisters’ hobnail boots and the iron wheels of the collecting prams were a common sound on Wellington’s streets. Delivery methods may have changed, but the kitchen still operates in accord with Aubert’s values: caring for people of all creeds and none. Located a block up from Moore Wilson’s food market, the institution is housed in a large red-roofed building decorated with distinctive murals. “Delicious soup today, team,” says one man, as he drops off his tray at the serving counter. Earlier, this same guest — as the staff refer to visitors — had been chanting something about demons. It was funny, a bit of goodnatured provocation. According to Gary Sutton, the genial, soft-spoken manager, the soup kitchen provides between 2400 and 3000 meals a month. The staff don’t ask questions and they don’t discriminate. “You could be a rapist or a murderer,” Sutton says. “That doesn’t matter. If you need kai, we will give it to you.”

When she moved to Wellington in 1899, Aubert was convinced there was more than enough food and clothing going to waste to sustain her charitable works. That remains the case. When donors don’t come through, there’s always St Joseph. A statue of the saint sits at the back of the industrial-sized kitchen, a large space full of gleaming stainless-steel surfaces and rows of smoked-glass mugs for coffee and tea. Sutton recalls a famous incident when one of the sisters placed a small potato under the saint; not long afterwards, a man showed up with a trailer full of them. “They made a huge mistake,” he says, laughing. “They realised they should have put big potatoes.” Whether or not St Joseph interceded is, of course, a matter of faith. But you need faith when it comes to saints. You also need patience.

Suzanne Aubert — also known as Mother Mary Joseph Aubert — drew on traditional Maori knowledge to develop herbal medicines and remedies. Image: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Two men enjoy a feed at the soup kitchen.

Father Maurice Carmody knows about the difficulties of saint-making better than most.

A thoughtful, bespectacled man, Carmody is a fluent Italian speaker who used to work in Rome as a history professor. He returned to New Zealand about 15 years ago — so he wouldn’t forget his roots, he says — and started working as a parish priest, most recently in Plimmerton, a coastal suburb north of Wellington. In 2020, experiencing severe illness, Carmody resigned his post and moved into a retirement complex in Porirua, a short train ride from the capital. Outside, wind and rain are lashing at the window. Inside, the apartment is cosy. On a side table, there’s a copy of the Dominion Post open at a half-finished cryptic crossword. On the walls, there are pictures of Jerusalem, or Hiruhārama, the place where Aubert founded her congregation on the Whanganui River. After a lifetime studying and teaching, Carmody has a patient, scholarly air. Reaching into his bookcase, the 75-year-old pulls out one of his published works: a history of the Franciscan Order. It was translated into Korean, someone joked to Carmody, because it was so big it could be dropped on the North as a bomb. Compared to the red, clothbound positio sitting on the kitchen table, however, it’s nothing. Carmody spent several years compiling the weighty book, an exhaustive summary of Aubert’s life and works, after being appointed postulator in 2010. The work to make her a saint, though, started decades before that.

Not long after Aubert died in 1926, the Sisters of Compassion received a prompt from Rome suggesting they start archiving material for a future canonisation attempt. The little nun was highly regarded in Italy, a country she travelled to in 1913 to meet the pope and ask him to give her new religious congregation greater independence from local church authorities. Stranded by the outbreak of World War I, Aubert wasn’t able to return to New Zealand until 1920. In the intervening years she volunteered as a nurse, caring for victims of a major earthquake and other wounded. Her work left an impression in the eternal city. From her death onwards, Aubert has had supporters who, due to her selfless charity and continual support for the sick, disabled, poor and vulnerable children, consider her a fitting candidate for sainthood. Events like the depression of the 1930s and World War II stalled things, but the sisters and a succession of postulators didn’t give up. In 1997, a conference of New Zealand Catholic bishops agreed to support the introduction of Aubert’s cause, helping pave the way for a diocesan inquiry, which took place in Island Bay in 2004.

Enter Carmody. After he returned to New Zealand and took up his post as a parish priest, the sisters approached him to help translate some letters in Italian relevant to Aubert’s cause. Recognising his language skills and connections in Rome, they drafted him in as the latest postulator. Carmody worked on the positio for several years, sending off numerous documents to Italy in sealed diplomatic bags and collaborating with colleagues in Rome to make sure everything was included. Now, flicking through the pages, he stops to explain various sections: annotated transcripts from the diocesan inquiry; a page from Aubert’s financial accounts, written in her beautiful cursive; a chronology of her life; a letter from a French bishop expressing support for the cause. Like those writing a thesis, the historian admits to odd moments of doubt — “you think, ‘Will I ever finish?’” — but he enjoys the work and sincerely believes in the value of the project.

Father Maurice Carmody reads the positio he compiled for Aubert’s cause in Rome. Photo: Oliver Lewis.

“I’m convinced that she’s a saint in the church understanding of a woman who really lived Christian values to the full,” Carmody says. “But also I’m convinced her story needs to be told much more widely.”

The positio had to be tested and accepted before Pope Francis could declare Aubert to be venerable. The Argentinian, considered a somewhat unorthodox holy father, made the announcement unexpectedly, as part of a regular address in Rome. You can tell Carmody is proud his work was vindicated, but when I ask him about the timeframe for the next steps, beatification and then sainthood, he sighs. “It can take 200 years sometimes,” he says. “I wish it would be over tomorrow, but we’re caught with the Roman system.” Currently, authorities in Rome are weighing up evidence for the first alleged miracle attributable to Aubert.

Because the matter is sub judice, Carmody and others are unwilling to share too many details. What is apparent, though, is the alleged miracle concerns a healing: a woman who was being treated in intensive care in Wellington. Doctors were discussing palliative care options, but the woman allegedly recovered after her family and church group prayed to Aubert for intervention. Carmody, who describes the healing as remarkable, investigated the event in 2019, collecting doctor’s notes, scans and witness statements. Each new alleged miracle considered worthy of investigation requires a fresh batch of evidence — an earthly jumble of paperwork needed to rubber stamp an act of the divine.

That same year, in 2019, the Māori king, Tuheitia Potatau Te Wherowhero VII, met with Pope Francis in Rome during a visit to Italy. Video from the historic meeting shows the two leaders — the pope in his white cassock, the king in a finely cut suit — sitting across from each other in the opulent surroundings of the Apostolic Palace. They were meant to meet for just 15 minutes. Sitting outside the chamber, Archdeacon Ngira Simmonds, the king’s chief of staff, recalls joking with the pope’s secretary. “I remember at 33 minutes, we were all going, ‘For goodness’ sake, these two! Hurry up.’”

Clearly, the two men had a connection. The king isn’t Catholic, but the Kiingitanga has had a long relationship with Christianity and the Roman Catholic Church. When the meeting was being set up, Simmonds spoke with local Catholics who asked if the king could raise Aubert’s cause with the pope. When the two dignitaries met, Kiingi Tuheitia handed the pope a letter inside a blue envelope. In it, the king invited the pope to visit Aotearoa and Tūrangawaewae Marae; he also expressed his personal support for Aubert’s canonisation. The endorsement took into account her work among Māori communities, use of rongoā Māori medicine and ability to bring Māori and Pākehā together, Simmonds says.

There was also the small matter of New Zealand not having any Catholic saints. Simmonds, an Anglican, says the king raised this as a reason for supporting Aubert’s canonisation, telling the pope something like, “We think it’s time we have our own [saints] coming from here.”

The nun was known for her work with children. With the Sisters of Compassion she established a creche as well as an orphanage in Wellington. Photo: The Sisters of Compassion.

There are already pilgrims making their way to the Home of Compassion in Island Bay. Not long after they arrived in the capital, Aubert and the sisters had started buying land in the windswept coastal suburb to establish their home for vulnerable children (it later served as a training hospital). Aubert’s remains were moved to the Island Bay complex in 1950, 24 years after her death. In 2017, in anticipation of increasing numbers of pilgrims, the sisters moved Aubert’s remains again, this time to a purpose-built annex off the home’s chapel. A tomb of grey river rock commands the room. Aubert was born in France, but she lies under a slanted wood ceiling curved in imitation of a waka. Shifting colours play across the polished floor, dancing gently over the tomb from a stained-glass window. Outside, Mary cradles the dead Jesus — a statue of Our Lady of Sorrows.

Sister Margaret Anne Mills, the current congregational leader of the Sisters of Compassion, is convinced miracles and blessings attributable to Aubert are happening all the time. The many visitors who come to ask Aubert for help are equally certain. It might be for minor things — marriage problems or depressive thoughts, for example — but if something shifts, the sisters note it down in a book of favours. From the most vulnerable to men dressed in expensive winter coats, the indefatigable nun attracts a diverse crowd. In life, one of her favourite sayings was: “There will be plenty of time for rest in eternity.” Well, perhaps not.

Aubert was born in June, but when I visited Island Bay last August the brick hallway to the chapel was still hung with children’s drawings of birthday candles. “We hope that you have a heavenly birthday,” one child wrote. “We miss you.” When she came to Aotearoa in 1860, Aubert was just another missionary from the other side of the world. She died a New Zealander, respected and loved by Māori and Pākehā alike. On Tory Street, a large portrait of Aubert looks down from the side of the soup kitchen. The Wellington hungry know her, but as the years go by the wider public has become increasingly oblivious. A nod from Rome would change that. If Rome approves the current alleged miracle, Aubert will become blessed. One more, and Aotearoa will finally have its first saint.

According to their website, the sisters are hopeful for a decision from church authorities on the first alleged miracle “soon”. But speaking to Mills, you get the impression that, for her anyway, the canonisation process, with its endless scrutiny and reams of paperwork, is less important than the facts that make up Aubert’s life — her Christian example. A spry, fit woman of 68, Mills was out walking in the bush-clad hills behind the Home of Compassion in 2016 when she heard Aubert had been made venerable. For her, that was the “gold medal”. Historians and theologians had picked Aubert’s life apart and found nothing wanting. Locally, the sisters and others already know Aubert to be a holy woman.

“We’re not waiting on Rome,” Mills says. “We know.”

Aubert’s final resting place in Island Bay. The nun’s remains are housed in a purpose-built annex off the chapel at the Sisters of Compassion’s home for vulnerable children. Photo: Paul McCredie, NZIA.

Oliver Lewis is a business journalist with an interest in Catholicism.

This story appeared in the February 2022 issue of North & South.