The Shocking State of Dental Care

It’s the gaping abyss in our health system. Why can’t we fix it?

By Helen Glenny

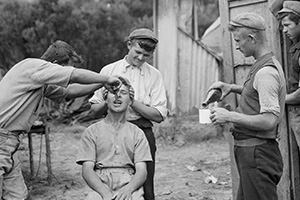

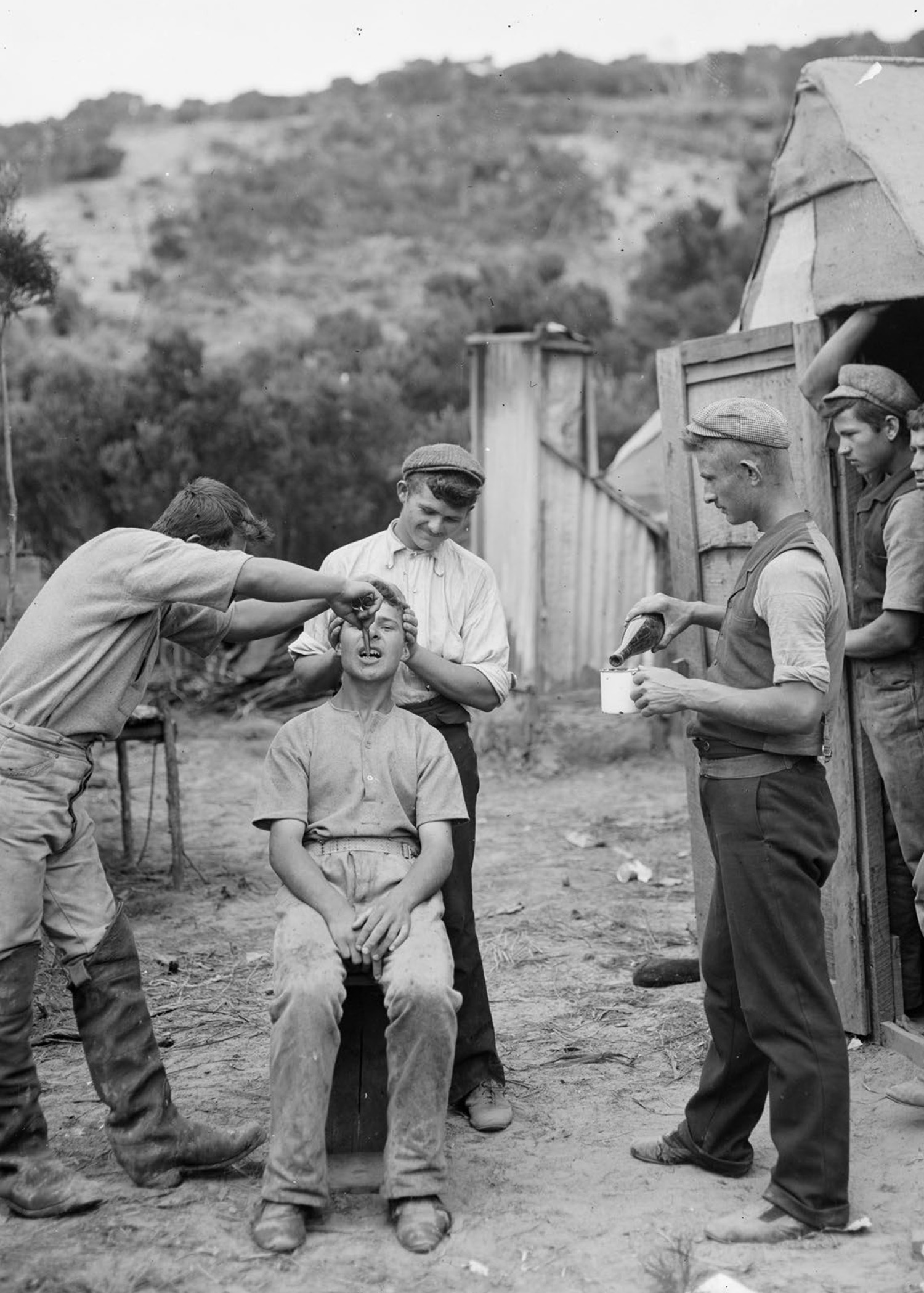

Gum digger having a tooth extracted, circa 1910, probably in the Northland region. Photo: Northwood Brothers, Alexander Turnbull Library.

In early 2020, volunteers gathered in Tauranga to prepare a 48-metre container ship for an unusual ocean voyage. The Trinity Koha was loaded with a caravan and a shipping container set up as mobile dental offices — both containing a dentist’s chair kitted out with bright lights and spit sinks. Working with an organisation called Youth With a Mission (YWAM), Kiwi volunteer dentists planned to provide care throughout the Pacific. Then Covid hit, and the countries they’d prepared to visit shut their borders. That’s when the volunteers realised that there was more than enough need on our own shores.

The organisation reached out to a local hauora centre in Welcome Bay and told them that if they found the patients, the team would show up with the mobile office and do basic dental work for free. By day three, there were 200 people on a waiting list. Some people who showed up at the clinic had been pulling out their own teeth at home.

Richard was a 59-year-old grandfather from Tauranga. His teeth were both broken and rotting. Unable to afford to see a dentist, he’d resigned himself to living with the debilitating pain and shame he felt about his appearance. At the clinic, he had 22 teeth removed. It was a previously unimaginable respite — and also just the beginning of restoring him to health. “Then koro had no teeth,” says Marty Emmett, YWAM Ships Aotearoa’s managing director. Since then, a local charity has contributed to the cost of dentures and given him budgeting guidance so that he’s been able to pay for the rest himself.

Another patient, Caroline, heard about the dental initiative through her church and came in for four fillings on her first visit and three on her second. Like Richard, she was deeply grateful for the relief from the pain, but it wasn’t a permanent solution.

Originally from Scotland, Caroline has had major problems with her teeth for years. In the United Kingdom, she’d received free or low-cost dental care through the National Heallth Service. After moving to New Zealand, she was racking up $500 to $600 in bills every year. Formerly a nurse, she is unable to work due to chronic back pain and lives on a sickness benefit.

Caroline took out Work and Income loans for some treatments. But they didn’t come close to covering the $15,000 to $30,000 she needed for jaw surgery, braces and veneers in order to avoid losing her teeth. Nor can she afford dentures, which would cost at least $1,000. That kind of specialist care isn’t something a charity like YWAM can provide. “I just want people to be able to see dentists like they see doctors,” Caroline says. “You should be able to get treatment, and not suffer pain like I’ve had to.”

Emergency department staff regularly see patients who have attempted DIY extractions with a screwdriver.

Dental care in New Zealand is the gaping abyss in our health system. It’s the one area where we expect adults to front up the full cost of necessary care on their own, in the private market — even though dental problems have been linked to all kinds of major chronic health conditions. (See Love Your Gums, below.) Forty-four per cent of New Zealanders say they avoid visits to the dentist because of the cost. And while basic care remains free for children up until age 18, the system often misses those who need it most. Between 2004 and 2014, the number of children treated under general anaesthetic for preventable decay increased by 65 per cent, and the number of children being treated in hospital is still climbing.

Those numbers don’t fully convey the underlying desperation. In 2020, people queued in the early hours at the port in Lyttelton, ready to pay cash for illegal treatment on cargo ships, according to a Stuff report. Charity organisations and emergency department staff around the country regularly see patients who have attempted DIY extractions with a screwdriver to escape pain that keeps them from eating, concentrating or sleeping.

The stigma of bad teeth also damages employment prospects, relationships and social connections. Emmett described a woman who’d come into the clinic who was “too embarrassed to even apply for a job because she was full of shame at how bad her teeth were”. She expected to have her front teeth removed because they were so decayed, but a volunteer dentist was able to rebuild them. When the volunteer dropped her back home, she told them, “I have my life back.”

Our poor oral health can partly be explained by eating habits, as highly processed and sugar-rich junk foods have become cheaper. But lack of access to regular dental treatment is a far more fundamental problem. Calls to bring dental care into the health system, or subsidise it the way we do for medical care, have never gone far, and while right before the 2020 election, Labour promised a major boost for emergency dental grants, it has yet to follow through. As a country, why are we doing such a terrible job of looking after our teeth?

Dental assistant Deborah Ussery (left) with dentist Phoebe Chua. Photo: Courtesy YWAM Ships, Aotearoa.

It’s hard to imagine that New Zealand once created a dental system so successful that many countries rushed to imitate it. In the early 1900s, when New Zealand was developing a reputation as a “social laboratory” for the rest of the world, a group of dentists called for publicly funded dental care for children. A dentist named F W Thompson had examined children at a Christchurch primary school, and discovered that most of them had teeth too decayed to save. But although the government rapidly expanded welfare services, dental care was not included.

It took the outbreak of World War I for that to change. Large numbers of recruits failed their medical exams because of the terrible state of their teeth. With help from the New Zealand Dental Association (NZDA), the Dentals Corps was formed. It ensured that soldiers were “dentally fit” for deployment, as well as providing emergency care in international theatres of war. The NZDA’s president, AM Carter, vowed to continue the fight at home once the conflict was over: “The war of the nations will end, and in our hearts we know Victory will be ours, but in the dental disease so rampant in our schools we have a more insidious foe.”

After the war, the New Zealand Dental Association successfully lobbied the government to establish a school dental nurse programme. The logic, according to some histories, was that women were “temperamentally and psychologically more suited than men to deal with the ailments of very young children”. Plus, since women in the public service had to stop working when they married, dental nurses were unlikely to set up their own practices — a comfort to male dentists of the era. By 1928, more than 70 trained dental nurses were working in purpose-built clinics or classrooms, community halls and hospital buildings.

Children taking part in tooth brush drill, Te Kaha school, Opotiki. Photo: John Dobree, Alexander Turnbull Library.

“I just want people to be able to see dentists like they see doctors. You should be able to get treatment and not suffer pain.”

During this period, Māori nurses were also treating students in “Native schools”, where the need for dental care was less dire. “I have never seen such beautiful teeth,” observed a nurse in Rotorua in the 1920s. “I can’t remember extracting a tooth from a Māori child.” When Maori started to adopt “westernised” diets, their oral health rapidly deteriorated, and by the mid-1930s, Māori children living in “white centres of population” had the same levels of tooth decay as European children.

That decade, as part of the push to introduce free universal health care, the First Labour Government consulted the NZDA about extending free dental care beyond primary school age. By then, the School Dental Service was extremely popular. Just as the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association successfully argued against free GP visits, the NZDA opposed the suggestion that dental nurses could also treat adolescents and adults — reportedly out of fear of competition for patients.

The success of the school dental system can be partially measured by looking at the extraction-to-filling ratio. Extractions were performed on teeth beyond saving; fillings were performed on less damaged teeth. In 1921, there were 114 extractions for every 100 fillings. By 1945, that had dropped to just 6.3 extractions for every 100 fillings.

In the 1950s, New Zealand became one of the first countries to introduce fluoride into the water supply in some places, which, according to one report, reduced dental decay by half for 13 -15-year-olds. The 1970s saw the introduction of a 30-minute “preventive appointment” to educate children on how to care for their teeth. Between 1976 and 1981, fillings in permanent teeth were reduced by 64 per cent. Over six decades, New Zealand had come to be considered a world leader in dental services for children.

That started to change with the seismic shifts in economic and welfare policy in the 1980s and 1990s. New Zealand quickly went from having one of the lowest rates of income inequality in the OECD to one of the highest by the mid-1990s. All of this resulted in more people living in poverty, and this history can be seen in the teeth of New Zealand children.

Even though care for under-18-year-olds remained free, some DHBs were unable to recruit enough dental therapists to treat them. Waiting lists grew, meaning visits weren’t occurring at the intended frequency.

A 2006 reorganisation of child dental health services out of schools and into community clinics produced some improvements, a Ministry of Health evaluation found. But early childhood tooth decay has been on the rise — in Canterbury, for instance, it went from 16.6 per cent of children in 2009 to 23.3 per cent in 2013.

And once you pass the age of 18, you’re on your own. “Inequalities in treatment are suppressed until a student finishes school,” says Jonathan Broadbent, Professor of Dental Public Health at Otago University. “By the age of 26, a few short years after a publicly funded system finishes, they open up, and they open up really wide.”

Love Your Gums

Dental issues aren’t just toothaches. They can lead to chronic pain, malnutrition and infections. Oral health problems predispose people to a range of chronic conditions, from cardiovascular disease to pancreatic and oral cancers.

Gum disease, or periodontitis, is a major oral health issue that needs to be fixed by a dentist. It occurs when your immune system tries to control the bacteria that build up around your teeth and your gums get damaged in the process. This can create pockets in your gums that get filled with bacteria and become infected. The infection harms your gums, but also the bones that support your teeth. If left untreated, it can cause you to lose teeth.

It’s also thought to contribute to a host of other health problems. People with gum disease are more likely to develop heart disease, and have more trouble controlling their blood sugar, which can cause, or worsen, diabetes. Women with gum disease are more likely to give birth pre-term than those with healthy gums. A recent study from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that people with gum disease had a 43 per cent higher risk of developing oesophageal cancer and a 52 per cent higher chance of developing stomach cancer. Gum disease has also been linked to the onset of pancreatic cancer.

It’s not entirely clear whether gum disease directly causes these conditions, or whether there are concurrent problems because of a separate issue, like damage caused by smoking. Regardless, gum disease needs to be treated by a dentist to prevent harm to your health. This usually includes scaling to remove plaque, laser treatment, medication or a surgical procedure to clean and tighten the gums.

There’s also evidence that the bacteria that builds up in your mouth can spread through your blood to your heart, contributing to the development of endocarditis, an inflammation of the lining in your heart, which can be life-threatening. Bacteria from your mouth can also predispose you to other kinds of cardiovascular disease, or make its way into the lungs, putting you at risk of pneumonia.

Ask anyone who’s scoured GrabOne for a cheap dental deal: taking care of your teeth is expensive. A check-up with X-rays and pain relief will set you back $153 on average. An old-fashioned silver amalgam filling starts from about $170, with white composite fillings starting from $190. Over a lifetime, the average Kiwi will have to pay out of pocket for 14 fillings — assuming that they stay on top of their appointments and nothing else goes wrong. Wisdom teeth removals, root canals or treatments for gum disease are even more costly. Collectively, we spend $1.2 billion of our own money on dental work each year.

For the many people who can’t afford it, the only public assistance available is a $300 emergency dental grant for individuals over 18 who earn less than $30,742 per year (the income threshold is slightly higher for couples and solo parents with children). Between 2016 and 2020, grant applications increased by 20,000, up to 87,000 per year. The grant has been $300 for the past 25 years.

Three weeks before the 2020 election, the Labour government promised to boost that to $1,000, but the money still hasn’t materialised. (Last year, Minister of Health Andrew Little told Newshub he’s still committed to the increase: “That’s our promise we went with into the last election, we haven’t got it in this Budget, we’ve got two more to go, and I’m determined we will fulfil that promise.”)

When the $300 grant doesn’t cover the bill, low-income adults can request a loan to pay the remainder. The average loan in 2021 was $704, up from $480 five years earlier. Tavia Moore works for Christchurch’s Beneficiary Advisory Service, where most of her clients needing emergency work wind up with a bill that exceeds what the grant offers — “even when people are accessing the cheaper dentists,” she says. “Quite often we see clients borrow upwards of a thousand dollars, if not a couple of thousand.”

For beneficiaries, Work and Income loans are repaid directly out of their benefit, which may already have regular deductions for furniture grants, bond assistance and rent. If WINZ doubts the person’s ability to afford basic necessities, it can reject dental loan applications. “The issue is that they don’t have anywhere else to go,” says Moore. “A lot of dentists now do an afterpay-type system. So a lot of people are turning to those sorts of options, or payday loans, which are not sustainable, and they end up with debt in multiple places.”

But the issues with the emergency grant are only a small part of the problem. An increase would do nothing for the even larger number of New Zealanders who sit in the in-between — earning too much for emergency assistance but struggling to afford necessary care. Jake, a 26-year-old camera operator from Auckland, has a wisdom tooth growing in, pushing on his teeth and causing him daily pain. He manages with painkillers because he can’t afford to get the tooth extracted. Louise, 34, from Christchurch, went to her dentist last month and was told she had a suspicious bump on her gums. She’s scared of what it could be — but doesn’t have $400 to see a specialist to find out. Those costs are magnified if you live a long way from the nearest dentist: a resident of Wairoa, for instance, needs to take a day off work and travel more than 100 kilometres for a check-up, since the town hasn’t had a dentist for adults for more than two years.

The Ministry of Health offers some advice on its website for adults in these kinds of situations: “If cost affects whether or not you can see a dentist, the Ministry recommends that you shop around and ask about the fees for the treatment you require.”

To further compound the problem, the cost of dental treatment is growing, and those costs are being passed on to patients. “The more innovative things we can do to rehabilitate people’s teeth, the greater the inequalities are going to be, because we’re in a ‘money buys health’ system. It’s health as a commercial enterprise,” says Broadbent. “Just imagine how it would be in other areas of the health system if this were the case.”

On a rainy Thursday is towards completing one of his unfinished projects, free dental care. Just saying.”

In 2011, Anderton laid out a plan to progressively introduce free dental care — first to pregnant women and those over 65, then to the rest of the public in incremental age bands. The plan also included a bonding scheme, where dentists willing to work in rural areas could have student debt written off.

Needless to say, Anderton’s vision has not come to pass. One common explanation is its estimated price tag of $1 billion. The plan included a few options for funding this cost, including a levy on income similar to ACC or a levy on sugary drinks similar to those for tobacco and alcohol. (Sugary drinks are even worse for your teeth than sugary foods: bacteria in your mouth eats away at the sugar these drinks leave behind, which creates acid, which damages the enamel on your teeth. Constant sipping means your teeth are exposed to sugar and acid for longer.)

Broadbent is sceptical that dental care could be folded into the health system, mostly due to the difference in time and cost of a check-up at the GP compared to a check-up at the dentist, which takes longer and involves expensive equipment. “There’s no simple dental,” he says. “There’s a dental assistant involved, there will be instruments that need an autoclave for sterilisation, there will probably be X-rays. You’ve got to view it as the difference between a surgical environment and a physician’s environment.”

But often the conversation about costs omits the savings that would come from preventing minor, routine dental problems from becoming major, expensive ones. Less than half of all adult New Zealanders have seen a dentist in the past year, with that percentage dropping to about a third for low-income, Maori and Pacific peoples. The number of adults who leave dental issues until they’re so severe they get admitted to hospital is growing.

Helen Wilson volunteering at the Trinity Koha Dental Clinic. Photo: Courtesy YWAM Ships, Aotearoa.

Even in the much-maligned US health-care system, 77 per cent of Americans have access to funded dental care.

The NZDA has calculated what it would cost the government to fund an exam, a clean and X-rays each year for the lowest-earning 40 per cent of adults, as well as treatment of gum disease, fillings, extractions and dentures. The upfront costs would be between $187 and $450 million annually — but the government could expect $1.60 returned on every dollar spent. This would come from savings to DHBs by reducing oral health issues that have to be treated in hospitals — as well as the tax revenue from increased productivity, given the impact of dental problems on employment. (By comparison, the Labour government’s initiative to expand access to mental health services costs $113 million per year.) Another report prepared for the Ministry of Health found that the net savings from extending fluoridated drinking water to the whole population would be more than $600 million over 20 years.

Meanwhile, plenty of countries have found a way to do something in between the free universal dental care that Anderton proposed and the fully privatised model we have now. Even in the much-maligned US healthcare system, 77 per cent of Americans have access to funded dental care.

The United Kingdom offers subsidised care under the National Health Service. There are three standard charges based on the “band” of dental care required. Check-ups, preventative work and diagnosis are included in the lowest band, fillings and root canals in the second, and crowns and bridges in the third. There are often long waitlists, and many UK dentists prefer to work in the private system, but NHS dentists still manage to see 55 per cent of the UK population each year.

In Europe, many countries have compulsory state health insurance that covers basic dental. The Czech Republic has one of the highest uptake rates of dental care anywhere in the world, with most citizens seeing the dentist twice a year. Their system covers pain relief, check-ups and fillings. Anything on top of that comes under an affordable payment scheme.

A 2018 study showed that our comparative lack of dental support here translates directly to worse teeth. The study looked at untreated tooth decay in New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States. New Zealand not only had the highest levels of decay, but also the greatest inequality in dental health between high- and low-income earners. Despite issues with dental systems in those countries, compared to ours, they’re working.

In 2018, then-Minister of Health David Clark asked for a briefing on the state of oral health in New Zealand. It painted a desperate picture. The Ministry recommended extending free dental care progressively up to age 26, a one-off annual check-up for Gold Card holders, and funded basic care for low-income pregnant women and those with children under five. These recommendations didn’t even become public for two years, when Newshub managed to obtain a copy of the report. When Chris Hipkins, who’d by then replaced Clark as the Minister of Health, was asked what had been done during that time, he pointed to progress in mental health and the unanticipated demands of Covid. But dental care? ”We haven’t got any particular commitments to make at this point on that.”

And so in the absence of government action, charities and other institutions are doing their best to fill the gaps. Two years ago, the University of Otago dental school began teaching at a “super-clinic” in South Auckland, where dental students can provide affordable care. Half of the first cohort of students who trained there in 2020 now work in high-need settings. Charities like Revive a Smile and YWAM provide free care to victims of domestic violence, former refugees, low-income adults and the elderly. They are proud of their work and keenly aware of its limitations. “We haven’t even touched beyond our own little province, the need is so great,” says Emmett of YWAM.

“There is just so much demand, more than we can take on,” adds Sue Cole, the organisation’s medical and dental facilitator. “And really, we’re just the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff.”

Helen Glenny is a freelance science journalist covering health, psychology and the environment.

This story appeared in the April 2022 issue of North & South.