Argo II

The untold story of how a pair of wily New Zealand diplomats helped the CIA save lives during the Iranian hostage crisis.

By Pete McKenzie

1. The Funeral

On a crisp winter’s morning in 1989, many of Wellington’s most influential diplomats, bureaucrats and consultants met in Old St Paul’s Church to farewell a dear friend. The man they were there to mourn was not a household name. But to the assembled gathering, Richard Sewell was a legend.

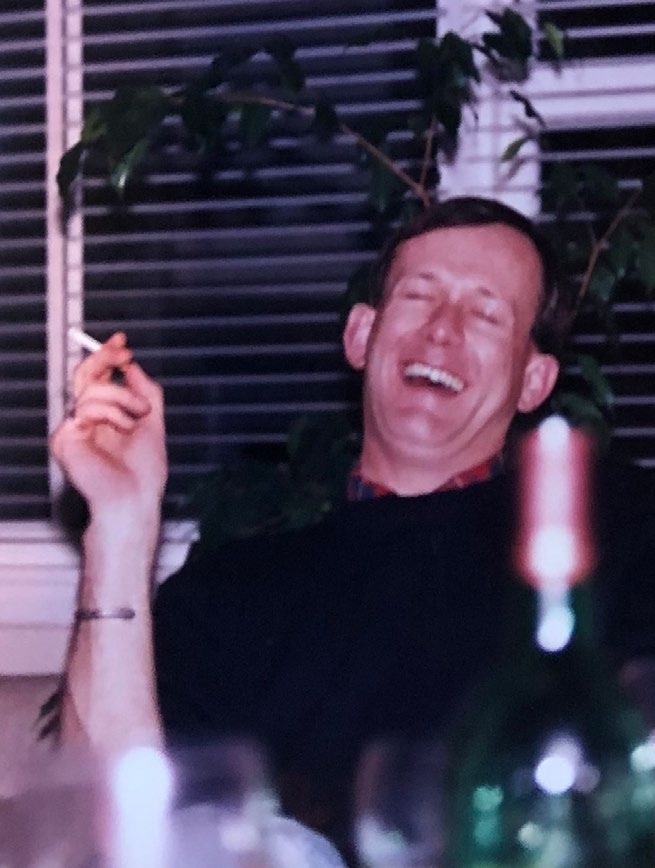

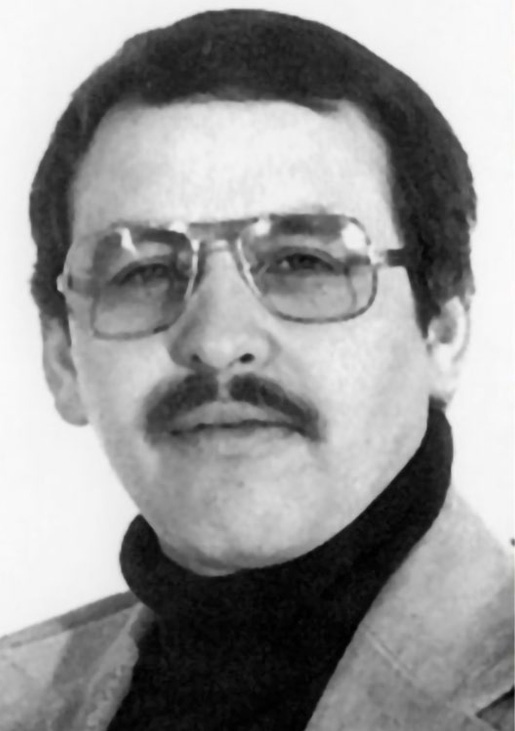

Six feet tall, with sharp features and a sweep of dark hair, Sewell had been a glamorous presence among the sallow figures of official Wellington. People found him charming, although they seemed to see different things in him. A “bon vivant”, one former colleague recalled: “The image of him is with a jersey slung around his shoulders and tied in front, with his hand to one side with a cigarette in it.” To another friend, he seemed more like a man straight out of the American Old West, with his firm handshake and the way he looked at you straight from his twinkling eyes. Sewell had such a rich social life that one attendee at the funeral almost expected his brick-like mobile phone to start ringing from inside the casket.

A few weeks before his death, Mattie Wall, a friend and former colleague at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT), had run into Sewell in a doctor’s waiting room. “I can’t get rid of this damn cough,” Sewell told her, she says. “And next thing he was in hospital.” she says. Sewell was among the first wave of people in New Zealand to be diagnosed with HIV/AIDS — only three years after male homosexual sex had been decriminalised, at a time when misunderstanding and prejudice about the disease was rife.

Even while confined to his bed in Wellington Hospital, Sewell tried to remain buoyant. He discussed with friends what his funeral should be like and what music would be played. He asked his close friend Chris Beeby, a colleague from New Zealand’s embassy in Iran from 1978 to 1980, to deliver a eulogy.

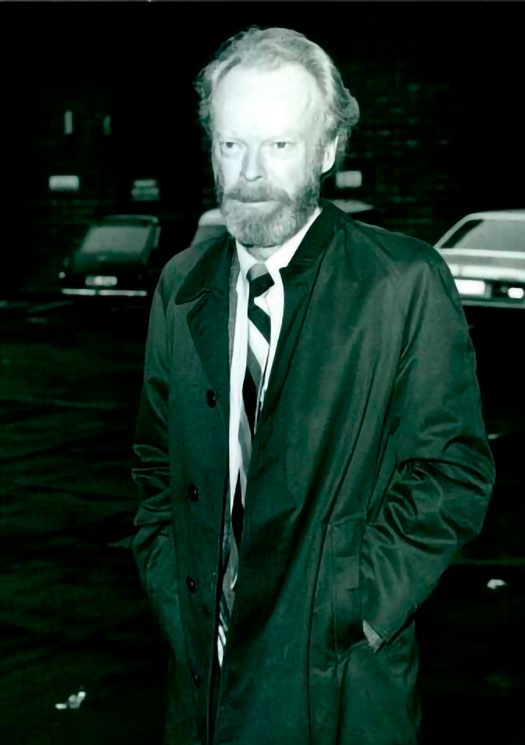

If Sewell was the model of a debonair diplomat, Beeby delighted in confounding expectations. “He fell outside my mental image of what an ambassador should look like,” says one person who encountered both men in Iran. “I always thought that Beeby was what the pirate Redbeard would have looked like in real life.” His craggy face was often partly obscured by a thick beard and framed by a wave of long red hair that sprouted at the crown of his head. Early in his career he represented New Zealand in the Gilbert and Ellice islands (now known as Kiribati and Tuvalu), navigating a boat through treacherous reefs around the atolls to attend important meetings. In his spare time, he was an avid fencer. He regularly eschewed the standard diplomatic uniform of a pinstripe suit in favour of a pair of jeans with circles of belt loops all the way down the pant legs.

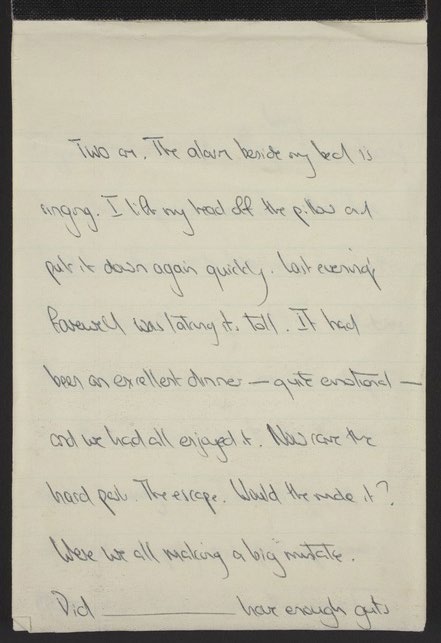

A page from Richard Sewell’s diary describing the Argo operation. Photo: National Library.

Richard Sewell. Photo: Supplied.

Standing at St Paul’s carved wooden pulpit, Beeby praised Sewell’s diplomatic skills and his loyalty as a friend and gossiped about his capers overseas. When he came to their shared time in Iran, however, he was uncharacteristically restrained. “There’s stuff we can’t talk about at this point in time,” he said. “But when the history is written of the evacuation of the Americans from Iran, great accolades will be paid to Richard for his role.”

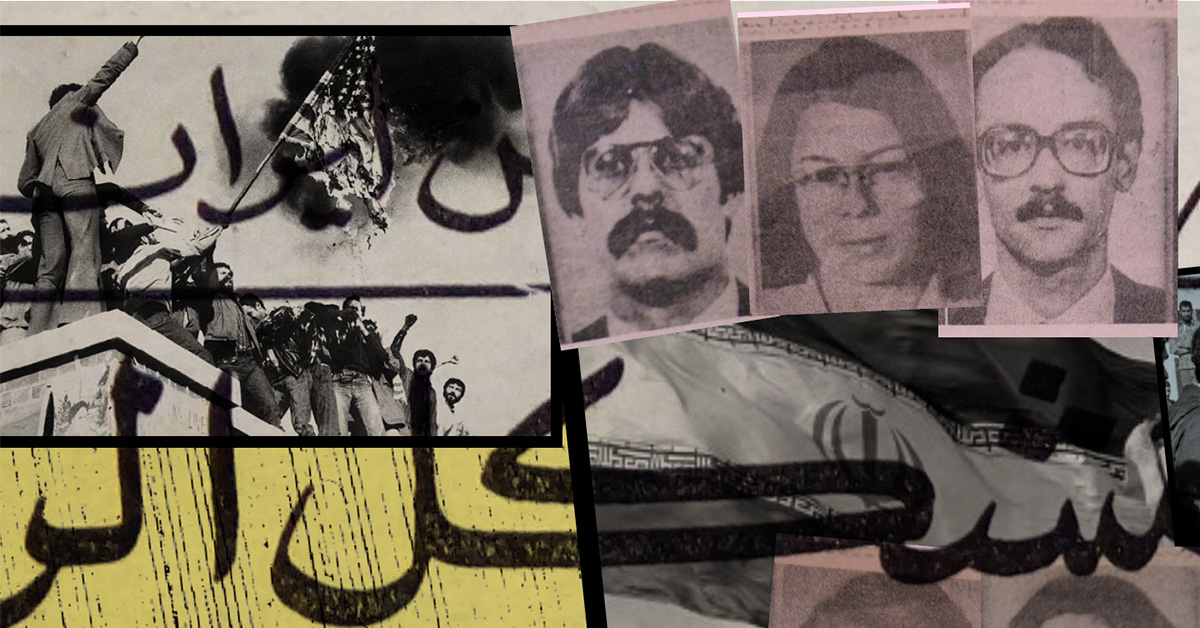

Beeby was referring to one of the most dramatic episodes of the latter 20th century. In 1953, America and Britain helped the Shah of Iran to overthrow the country’s democratically elected government. For 25 years American diplomats essentially controlled the increasingly repressive monarchical regime. In 1978, popular resentment finally erupted and the Shah was overthrown. Massive crowds of revolutionaries began gathering daily outside the American embassy in Tehran to chant “death to America”.

At 10am on 4 November 1979, a handful of university students began scaling the embassy’s 10-foot walls, including young women with bolt cutters hidden beneath their chadors. The embassy’s locked gates were broken open from the inside; US Marines couldn’t fire for fear of provoking a full-on war. One group of revolutionaries swiftly captured the compound’s main buildings and took dozens of American hostages. These hostages would be held for 444 days. The ensuing crisis would eventually bring down Jimmy Carter’s presidency.

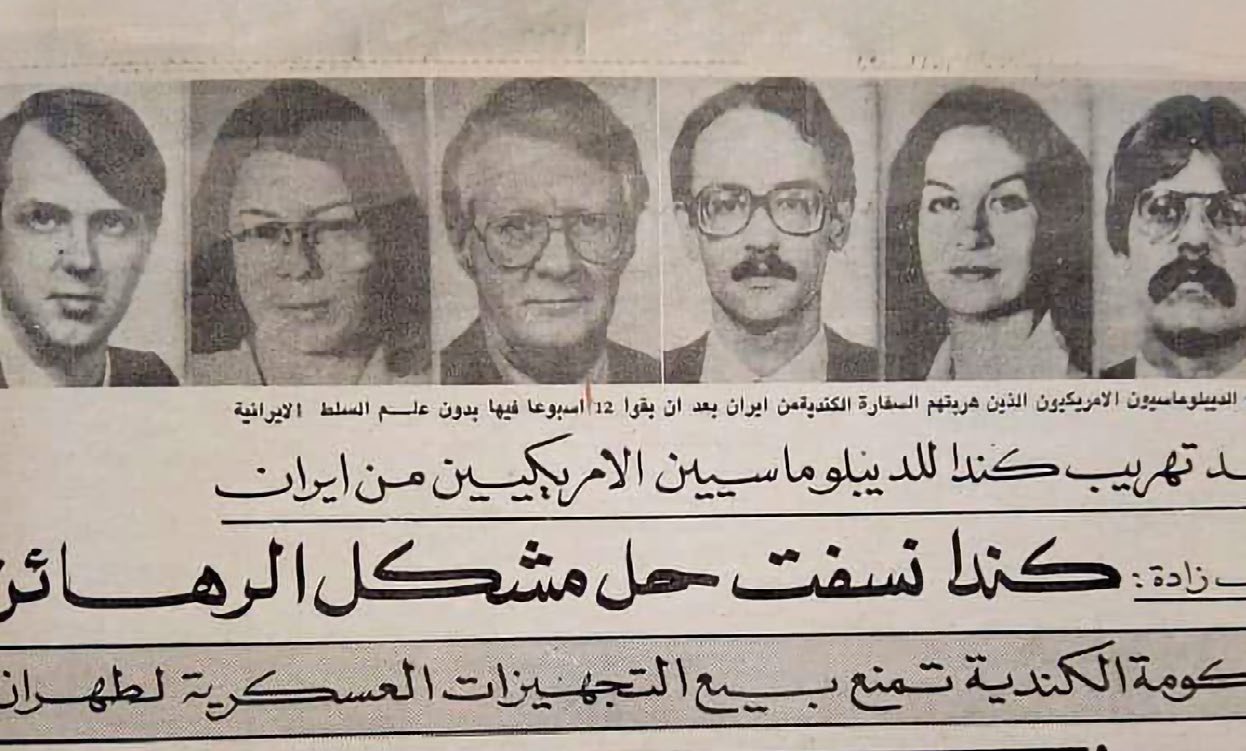

A handful of Americans managed to slip from the compound and take refuge in the Canadian embassy. Their story was dramatised in the 2012 Oscar-winning movie Argo, the codename of an almost-too-fantasticto-be-true CIA operation to smuggle the Americans out of Iran by disguising them as a Hollywood film crew. Beeby and Sewell aren’t mentioned in the film, but when reflecting on the Americans’ desperate search for help from various foreign embassies, one CIA character remarks (inaccurately) that the “Brits turned them away, Kiwis turned them away, Canadians took them in”.

At the time of the film’s release, this line of dialogue prompted a minor international incident. An indignant Winston Peters moved a motion in Parliament to censure Ben Affleck, the film’s director, and said that then-Prime Minister John Key should have “called the US ambassador in for a ‘clip over the ear’”. But the full story of New Zealand’s role in the Argo affair has never been told. In fact, Beeby and Sewell played a critical role in saving the lives of the six American diplomats. They salvaged the operation of one CIA agent, almost rescued another CIA asset, and were themselves forced to flee after their embassy was invaded by an angry militia bent on revenge.

After Sewell’s death, Beeby never spoke publicly about what happened; nor did he live to see Argo. Fearing repercussions, MFAT has not declassified its archives relating to this period. For four decades, Beeby and Sewell’s escapades have remained shrouded in rumour and confusion.

Through interviews with those who knew the two men, including some of the American diplomats, as well as an entry from Sewell’s diary and memoirs of the Iranian hostage crisis, I was able to piece together their starring role. When I called Mark Lijek, one of the Americans Beeby and Sewell helped save, he told me that he still gets angry that their bravery was never recognised. “My biggest gripe with Argo is that one throwaway line about the Kiwis,” he said on a phone call from his home in Washington state. “That’s such bullshit!”

Tony Mendez. Photo: Supplied.

Chris Beeby. Photo: Supplied.

2.The Plot

When the Iranian revolutionaries surged through the American embassy’s gates, a second group streamed northeast towards the small consulate where exit visa applications were processed. For two hours, a single Marine kept them at bay. Finally, the Americans inside slipped out a side door into the pouring rain. Only five of them managed to evade capture on the streets. For six sleepless days they moved from house to house until the Canadians offered them safe haven.

The Americans were led by Bob Anders, the affable, even-keeled head of the US consulate’s visa section. He stayed in the residence of John Sheardown, the Canadian immigration chief, along with Mark and Cora Lijek. Mark was 29, with a moon-shaped face, a mop of mousy hair and thick glasses. This was his first overseas posting, and his wife Cora, 25, had accompanied him to take up a role as a consular assistant. Calm and infectiously funny, she worked hard to keep the group together.

Another married couple, Joe and Kathleen Stafford, went to the house of Ken Taylor, the Canadian ambassador. Joe had joined the Foreign Service at the same time as Mark, but whereas Mark was outgoing and excitable, Joe was focused and determined. Kathleen, whose sweet, positive temperament balanced out her more intense husband, also worked as a consular assistant. They were later joined by Lee Schatz, a 31-year-old agricultural attaché with a bushy moustache who had escaped from another building. Schatz was the practical joker of the group. Cora remembers once asking him for a glass of water, only to find upon drinking that Schatz had filled her glass with vodka.

Taylor considered multiple options to get his houseguests to safety. They could drive northeast to Tabriz and across the border to Turkey, but that region was in revolt. They could go south to the Persian Gulf and seek passage on a tanker, but that would require passing through conflict-ridden Khuzestan. And so instead a caper for the ages was hatched: the Canadians would issue passports to their guests and pass them off as a Hollywood film crew scouting Tehran as a location for a movie. A CIA agent would fly in to help forge their documents, prepare their covers, and escort them out via Tehran’s Mehrabad International Airport.

This was not an operation that could be pulled together overnight. Genuine Canadian passports had to be prepared and delivered. The CIA’s leading exfiltration expert, Tony Mendez, had to create a plausible movie project; the CIA eventually bought the rights to an actual film script based on the 1967 science fiction novel Lord of Light. To make the cover story believable, Mendez reached out to John Chambers, a legendary make-up artist who worked on the Planet of the Apes franchise, and the two set up a functioning production firm on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles.

On 9 December, a month after the houseguests’ arrival, a reporter for a Quebec paper reached out to the Canadian government to confirm his knowledge of the hidden Americans. He agreed to hold off on publication until they escaped, but it wouldn’t be long until someone else figured it out. Taylor needed help. So he called New Zealand’s ambassador to Iran, Chris Beeby.

Beeby, who was then in his early 50s, had grown up in a high-achieving, globe-trotting family. He had joined MFAT after studying law at Victoria University and gaining a master’s degree at the London School of Economics. He notched a series of high-profile wins, including representing New Zealand at the International Court of Justice in its cases against French nuclear testing in the Pacific. By the time he was appointed ambassador to Iran in 1978, he had a reputation as a singularly talented diplomat.

During the Shah’s reign, the diplomatic community in Tehran had been vibrant. A different embassy would host cocktail parties practically every night. Following the revolution, such parties became fraught with danger. Mark Lijek went out to wingman a fellow American diplomat at one gathering, only for an armed militia to scour the event in search of alcohol and Iranian women being “corrupted”. Another night, he and his friend were arrested by the Revolutionary Guard.

Unsure whether his communications were secure, Beeby relayed messages via “circuitous language and Kiwi aphorisms”.

In this new climate, diplomats from larger embassies withdrew into their national bubbles. Those from smaller embassies limited their socialising to a select few countries. Beeby’s closest friend in Tehran was Taylor, the Canadian ambassador. Both were larger-than-life personalities with little appetite for formality. They forged a close connection and their junior diplomats followed suit.

Taylor sought Beeby’s help developing a backchannel with Iran’s second most powerful man, Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti. Beeby’s charisma and political nous gave him an advantage over other diplomats in negotiating with the new Islamic government. When religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini announced a ban on foreign meat imports in March 1979, Beeby had flown to the holy city of Qom and secured an exception for New Zealand in part by convincing a sceptical mullah to certify our lamb as halal. Taylor and Beeby hoped they could negotiate in a similar manner with Beheshti for the return of the American hostages, but their plan was ultimately rejected by the American State Department.

While preparations for the exfiltration were under way, Beeby and Sewell often dined with Taylor and the houseguests at the Sheardowns’ house. The younger Americans were particularly drawn to Sewell, who was closer to their age. “I knew that there were many Canadians, even, who were not interested in helping us,” Mark recalls. “Whereas Richard was eager. I appreciated that fearlessness.”

Sewell was born and raised amidst the quiet farms of Hāwera. His father had returned from World War II suffering from catastrophic PTSD, which consumed the attention of his mother Joan, a firm and long-suffering nurse. Sewell’s younger brother died at age four, and his father soon after, leaving him and his mother isolated. Every so often, though, Sewell’s aunt, one of the first women to work in New Zealand’s foreign service, would sweep into his life with glamorous stories of foreign capitals. Joan disapproved of her sister’s career, seeing it as “a bit too high-flying and artificial”, recalls Grant Allen, Sewell’s partner. But Sewell was inspired by his aunt’s example. He joined MFAT immediately after finishing university.

When he arrived in Tehran in 1978 as an eager 26-year-old to serve as the embassy’s second secretary, he kept parts of himself hidden. Under the new conservative regime, homosexuality carried a death sentence. Even among his colleagues, there was risk in revealing that he was gay. Beyond the personal prejudice harboured by many Kiwis at that time, there was a fear that homosexuality could leave a diplomat vulnerable to blackmail. Unsurprisingly, Richard never let on to the houseguests that he was gay. Indeed, he would often make a point of flirting with Cora and Kathleen.

The days settled into a strange routine, equally tedious and perilous. Each morning, Anders listened to the news bulletins for new information. Mark would wake at 10am and wander down to ask what was happening. “After a while, he wouldn’t want to tell me, because I’d always react so negatively,” says Mark, who struggled with a sense of paralysis as their confinement dragged on. On sunny days, Anders would go into the inner courtyard, take off his shirt and suntan on a recliner. Joe Stafford, who had a passion for languages, spent his time becoming fluent in Farsi. All the houseguests read voraciously. They played a lot of Scrabble.

Their dinners were boozy affairs. Sheardown had two years’ worth of alcohol in his house and Beeby helped restock the supply when he visited — a dangerous undertaking, since alcohol was illegal in Iran. Despite his courageous efforts, the houseguests ran out of alcohol within three months. “We really became friends with Chris and Richard through that experience,” says Cora. “We felt comfortable with them, could joke around with them. It felt close to normal.”

And yet danger was never far away. One day, Mark went into the kitchen and saw the neighbour’s Iranian gardener looking at him through the doorway. Mark kept his cool and simply waved at him, hoping the gardener would think he was one of the Canadian security officers at the residence.

With the risk of exposure growing, Taylor asked Beeby to lease an empty villa in an adjoining neighbourhood. Beeby paid down three months’ rent (allegedly with money provided by the CIA) and stocked the villa with provisions, while Taylor stationed two Canadian soldiers there to maintain it as a safe house. While in the end it was never used, it was an important precaution. The Canadians, Mark explains, “didn’t want their fingerprints on the house” because if they were compromised, anything with a Canadian connection would be suspect. “So New Zealand came to the rescue, and they signed the lease.”

The New Zealanders were also able to overcome one of the biggest obstacles facing the exfiltration effort: the immigration paperwork. Every visitor to Iran was issued with a unique disembarkation form. A white copy was kept by Iranian authorities. Visitors had to keep the yellow copy and present it to airport officials on departure. Only once the yellow and white copies matched up would they be allowed to leave. Of course, no such forms had been issued for the houseguests’ fictional Hollywood aliases.

Sewell, however, had formed a friendship with the Mehrabad Airport station manager for British Airways. He convinced him to provide a stack of blank yellow forms for the houseguests to scrawl their details onto. There was no way to lodge white copies with Iranian officials; the houseguests would have to rely on the immigration officer at the airport being too lazy to check.

Beeby and Sewell were putting themselves at great risk by participating in the plot. The American hostages being held at the US embassy were regularly beaten. Their hands were bound behind their backs for days at a time and many were placed in solitary confinement. Some of the Iranian jailors played Russian roulette with their hostages, while others rigged up mock electric chairs to intimidate them. Hostages described being threatened with boiling oil or with having their eyes cut out. Two of the Americans attempted suicide. Had the New Zealanders been caught, they might have faced similar treatment.

Yet they never revealed the slightest concern for their own safety. “Nothing seemed to faze Richard,” recalls Mark. Grant Allen, Sewell’s partner, says, “Chris and Richard would have been such a good team. They both had that sense of, ‘Well, let’s just fucking do this’.”

There were larger geopolitical pressures at play, as well. While Anglo-American machinations in Iran had focused on securing a vital supply of oil, for New Zealand the overriding foreign policy preoccupation was meat. After Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community, it could no longer be relied on to buy most of our agricultural exports. Diplomats were instructed to exploit every new market to overcome this major economic threat. In fact, this was the reason that New Zealand had established an embassy in Tehran in 1975. Iran quickly became one of our five largest export markets. When a major oil shock roiled the world in 1978, New Zealand negotiated a deal to barter our lamb for Iranian oil. Beeby did his best not to jeopardise these interests, Taylor later recalled. But at the same time, he “went considerably beyond [his] mandate. [He’d] do anything almost.”

When MFAT found out Beeby was helping the Americans, there wasn’t much it could do. According to his friend Brian Lynch, a former senior diplomat stationed in London, Beeby was unsure whether his communications were secure. So he would call Lynch and pass messages on via “circuitous language and Kiwi aphorisms”. He relayed that the revolutionaries had “knocked the bastard off” (a reference to the Shah), or that a particular militia had “gone the whole hog” in pursuit of a target. In these circumstances, it would have been difficult for Beeby’s superiors to give him formal instructions even if they had wanted to. And Beeby relished the independence. “He was actually quite enjoying it,” Lynch says. “All we could say behind a London desk or at the Ministry’s head office was, ‘Jesus Christ, fingers crossed’.”

3.The Escape

By January 1980, the houseguests had been stuck in the Canadian diplomats’ residences for three months. First Thanksgiving and then Christmas had passed in hiding. To minimise the risk of discovery, they were permitted no contact with the outside world beyond the visits of people like Beeby and Sewell. Every so often, they would get news about the hostages being kept in the American embassy, or how negotiations were progressing. For Mark, the news inevitably prompted him to rage. He couldn’t help but feel the houseguests and hostages had been abandoned by the American government. To distract himself, he read spy novels. “It was best not to think about the big picture politically, for my blood pressure,” he says.

Finally, on 25 January, two American CIA agents — Tony Mendez and another man known only as “Julio” – arrived in Tehran for the exfiltration operation, codenamed “Argo”. The next day, Sewell drove the Staffords from Taylor’s residence to the Sheardowns’ house, where the houseguests and Mendez met. Mendez was a diminutive man with a scruffy moustache, round cheeks and a distinguished career getting CIA assets out of tight corners. Mark Lijek was immediately struck by his resemblance to Sewell. They had the same visible self-possession, the same swagger, he thought. “In a different life [Sewell] might have been in a similar occupation. Who knows! Maybe Richard was.”

Mendez briefed the houseguests on the plan, which they were learning about for the first time. “I was hugely impressed,” says Mark. “It was obviously over the top, but in a positive way.” Not everyone, however, was on board. Joe Stafford couldn’t bear the thought of leaving while the hostages were still trapped in the American embassy. To him, it seemed like an unforgivable betrayal.

With a degree of frustration, Mendez emphasised that they had no other option and left the houseguests to pack and memorise the details of their aliases. The names and birthdays of their covers were variations on those of the houseguests’ parents. Mark’s cover, for example, used Cora’s father’s first and middle names. Luckily, they weren’t required to become instant experts on cinematography or screenwriting. Mendez had kept the details of their covers to a minimum, wary of overwhelming the houseguests with information and betting that there were unlikely to be too many Hollywood movie buffs working at the Tehran airport. That afternoon, Sewell and one of the Canadian diplomats, dressed in military fatigues, assumed the roles of Iranian immigration officers and began interrogating the houseguests. This part of the preparation was less successful. Sewell was too nice to make a convincing Iranian hardliner and the Americans couldn’t stop laughing.

Beeby and Mendez joined the group and at 7pm they sat down for what historian Robert Wright described as a seven-course “scorched earth” dinner with champagne and liqueurs, “the object of which was to leave no alcohol behind”. Even by the end of the meal, Joe Stafford was still on the fence; Schatz stayed up the entire night trying to persuade him to change his mind.

When the CIA needed a cover story, it turned to Hollywood. In New Zealand’s version of Argo, Copeland would be disguised as a Kiwi meat inspector.

At 2am on 27 January, in his small Tehran apartment, Sewell woke up, lifted his head off the pillow and promptly put it back down again. He had a pounding hangover.

Sewell had been charged with picking up Mendez from the Sheraton hotel down the road, using Beeby’s Chevy Suburban with diplomatic plates. This was vital to the plan; it would have been impossible for the Americans to rent their own car. “It was dark outside and cold,” Sewell later wrote in his diary. “The night was silent — none of the small arms fire and nighttime chanting we had gotten used to during the revolution.”

Sewell arrived at the hotel at the appointed time of 2:45am. He found the lobby eerily empty, except for a single reception clerk. When he called up to Mendez’s room, he had to wait a few long beats before Mendez finally picked up. “Jesus, is it time to go already? I’m still asleep. I’ve only just got back. What’s the time?” It took half an hour for the CIA’s top exfiltration man to appear downstairs, bleary-eyed and, like Sewell, very hungover. “Bloody hell. For God’s sake don’t mention this to anyone.”

In a stroke of luck, the route from the Sheridan to the airport was empty of militia. Sewell asked Mendez what would happen to them if something went wrong. “I suppose we’ll all be down at the Embassy with the rest,” he replied. “Maybe I’ll even be shot if they discover what I’m about.” For the rest of the way, the two men drove in silence.

Upon arriving at the airport, Mendez, who was posing as part of the fake film crew, checked his bags, snagged his boarding pass and took up position beside some large windows to signal the all-clear to the houseguests. The Canadians had arranged for the Americans to be driven to the airport in limos bearing the maple leaf flag. All of them showed up: Schatz’s late-night persuasion had worked and Joe Stafford had reluctantly agreed to the plan. The Americans were made up in various disguises — Mark’s beard had been coloured with mascara to give it a darker hue. Spotting Mendez’s signal, they moved through check-in. Sewell, meanwhile, had access to much of the airport thanks to his diplomatic ID. He went to speak to his contact at British Airways, then stationed himself in the departure lounge, ready to jump in if anything went wrong. To get to Sewell, the houseguests would have to pass through the immigration checkpoint — the most fraught moment of the entire escape.

Schatz went first. The Iranian official squinted at his passport. “Is this your photo?” “Of course,” Schatz replied, forcing himself to be calm. The official silently stood and walked into a back room.

The group watched in aching suspense until the official returned. “It doesn’t look like you,” he said, pointing to the photo.

Schatz suddenly relaxed. There was a perfectly good reason for the officer’s query: his passport photo was old and showed him with an enormous moustache. Schatz mimed clipping his moustache. “It’s shorter now.” The official paused for a moment, then shrugged and stamped Schatz’s passport. He didn’t bother matching Schatz’s white disembarkation form with its required yellow partner. Schatz sidled through.

The rest of the group followed, fighting furiously to keep their fear in check. Mark had realised moments before arriving that their passport pictures had been printed in black and white. Normally that was not allowed; he was anxious it would arouse suspicion. But security was lax. When Cora reached the immigration desk, it was empty; the officer had gone to brew some tea. She dodged around the desk and coaxed him out to examine their passports. “He barely looked at our papers,” she recalls. “Tony actually stole back the copies while he wasn’t looking.” With relief, the group took their seats in the departure lounge.

Then, minutes before they were meant to board, the airport PA blared with an announcement. The Swissair flight had been delayed by technical issues. The Americans couldn’t show it, but they were terrified. Had their cover been blown?

Again, Sewell’s contact at British Airways proved to be invaluable. He went to find out what was going on and returned a few minutes later to inform Sewell and Mendez that there really was a mechanical problem with the plane. Mendez and the houseguests discussed transferring to a British Airways flight, but decided that the last-minute change would be too risky. So the group returned to the hard airport seats for an excruciating wait. Joe Stafford picked up an Iranian newspaper to pass the time, only to hurriedly put it down when he realised a member of a Hollywood film crew was unlikely to be fluent in Farsi.

Finally, the boarding call sounded. The houseguests were walking across the tarmac when Anders noticed the name of the plane that would spirit them to safety: Aargau, named for a region of Switzerland. He turned, grinning, to Mendez. “You guys think of everything!” Within minutes, they were in the air. Within hours, they were out of Iranian airspace. They had pulled off one of the most audacious escapes in diplomatic history. But back on the ground, Sewell and Beeby’s work was far from over.

4.The Seventh Man

Two days before the escape, in Washington DC, Hal Saunders, the US Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, sat down to write his daily memo summarising the progress of a working group formed to deal with the Iranian crisis. His 25 January memo concluded with the following note:

We have asked the New Zealand embassy to assist an American, Max Copeland, who was prevented from leaving the country because of some unknown difficulty with the Ministry of Justice.

Copeland, a tall, quiet Oklahoman, had moved to Iran with his wife Shahin Maleki, an Iranian woman with an aristocratic background. He worked as an academic, then as an employee of the US aid programme, before drifting into doing odd jobs for Western companies in the country. When the revolution broke out, Westinghouse, a major American defence contractor, approached him for help shutting down its operations: auctioning off the houses of its employees, shipping goods stateside. That included US$48 million worth of advanced radar equipment which Westinghouse had sold to the Iranian Air Force. Learning of the shipment, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard arrested Copeland and charged him as a CIA agent.

In an Iranian prison, Copeland was interrogated by a soft-spoken man named Hassan. “Even your government doesn’t know you’re here. You are the forgotten hostage!” Copeland admitted nothing, but was convicted of espionage and sentenced to 20 years home imprisonment in his cramped Tehran townhouse.

Shahin and her son Cyrus believe Max was indeed a CIA asset with a “non-official cover” at Westinghouse — a make-work position allowing him to discreetly support the CIA’s operations. Cyrus later wrote a memoir of the family, Off the Radar, drawing on declassified American documents and conversations with Kiwi diplomats like the late Merwyn Norrish, New Zealand’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs between 1980 and 1989. The timing of Saunders’ memo, he wrote, was crucial:

Exactly two days before the Kiwis had driven the American diplomats to safety, the State Department had asked them to ‘assist’ my father. The wording on the memo was vague, but there was no mistaking what they’d asked for. Another extraction.

Argo had been a joint CIA–Canadian operation which Beeby and Sewell had assisted. The Copeland extraction would be a solely Kiwi affair. Beeby agreed to undertake the operation on the condition that it be run separately to Argo. That way, if one went wrong, the other could still be salvaged.

By 20 January, Copeland was in home detention. His wife and young children had flown to safety in America. That evening, Copeland’s doorbell rang. In Off the Radar, Cyrus describes what happened next, in a passage drawn from his father’s recollections.

“Hello, mate! Name’s Richard Sewell — but you can call me Moses,” said the tall man at the door. His easy demeanour reminded Copeland of an American frat boy. “Mind if I come in?” When Copeland looked wary, the man said, “Didn’t they tell you I was coming? Probably not, the lines aren’t the safest. How about a cup of tea?”

Sewell walked around Copeland and into the kitchen, forcing Copeland to hurry after him. “The State Department briefed us on your, uh, difficulties. It’s all being handled — can’t say exactly how, it’s quite clandestine — but you’ve got the attention of some interesting people, Mr Copeland. In fact, if all goes well, in two weeks’ time you’ll be on a plane out of Mehrabad.”

Sewell handed Copeland a State Department telex explaining who he was. Copeland was extremely sceptical about the prospect of an escape. “There’s no way I’m flying out of Mehrabad. One, my name is on the stop list. Two, I’m on a first-name basis with most of the customs agents — many of whom I’ve bribed. And three, they’re all familiar with my, let’s say, situation. They think I’m CIA.”

“Which is why you’ll be in disguise,” answered Sewell. “Beard. New glasses. The works. You, sir, are going to be an honorary Kiwi — and I am going to be your agent of transformation. We’ve got ourselves a properly clandestine operation here. Have you anything to eat?”

The two men sat in Copeland’s kitchen and, over a meal of kebabs, tomatoes and rice, Sewell explained what he had in mind. When the CIA was in need of a cover story, it turned to Hollywood. In the New Zealand version of Argo, Copeland would be smuggled out as a Kiwi meat inspector.

Although the American houseguests hadn’t yet escaped, Sewell made veiled references to his work with them to build Copeland’s confidence. “Max, listen to me, I’ve done my fair share of airport runs and gotten out of some fairly tricky situations. Early mornings, no one is paying attention. It’s winter. We’ll put you in a hat . . . maybe arrange for a diversion in the customs line. You’re in our hands, so let me worry about this, okay?” After a moment’s hesitation, Copeland nodded.

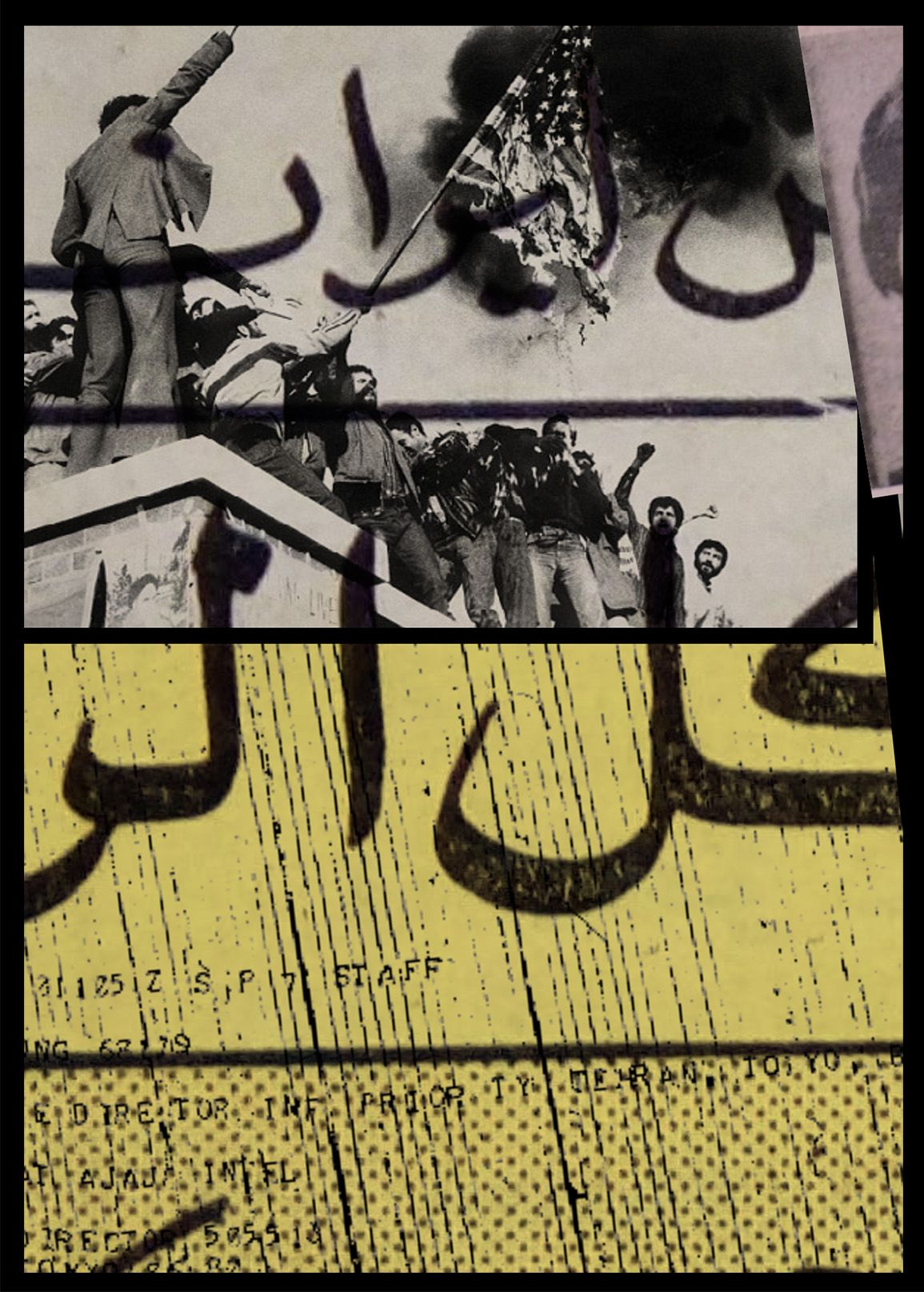

The diplomats (from left): Mark Lijek, Cora Lijek, Bob Anders, Joe Stafford, Kathleen Stafford, Lee Schatz. Photo: Assabah/Wikimedia.

Over the next few days, Sewell dropped off a thick file with the details of Copeland’s cover and a collection of brochures about New Zealand’s lamb industry. Copeland was to be a meat inspector named John Moffett. Wellington would issue him with a real passport, to be urgently mailed to Tehran. Sewell supplied various items to bolster his authenticity: lunch receipts, a pin with a Maori design, various bits of “pocket litter”. Somehow, he obtained a bag of fake facial hair, which they spent an hour trying out. Copeland eventually chose “The Professor” — a moderately clipped beard inflected with grey — and posed for a passport picture against a white sheet hanging on the wall. Sewell also gave Copeland a record titled Radio New Zealand’s Greatest Interviews and instructed him to play it “again and again until you sound like a Christchurch tour guide”.

Copeland’s flight was booked for early February. During his rushed initiation as an honorary Kiwi, the Argo exfiltration took place. The Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor and his staff left Iran on the same day. As soon as the Americans were safe, “The Canadian Caper” appeared on front pages across the world. In a press conference with hundreds of journalists, Taylor refused to comment on the mysterious rumours that there was a “seventh man” still trapped in Tehran.

Before departing, the Canadians had transferred their unclassified documents to New Zealand’s embassy for storage and asked Beeby to represent Canada’s interests in their absence. The connection was too obvious for the Iranians to miss. On the night of 4 February, a revolutionary militia ransacked the empty New Zealand embassy for clues. They hauled out loose documents and drilled into the embassy safes but missed the proof of the Copeland exfiltration by the smallest of margins: when they came to the safe with Copeland’s passport in it, their drill ran out of gas.

Beeby and Sewell arrived at work the next morning to find files scattered on the floor, desks overturned and the locks to most of the embassy safes broken. To make matters worse, they were told Ayatollah Khomeini’s Revolutionary Guard was hunting for them. One former MFAT official remembers Beeby calling the Ministry’s office in Wellington from various hotels around Tehran through the day, trying to figure out what they should do. Some hours later, they hopped on a plane out of the country.

That evening, Copeland got a call from Sewell and was shocked and furious to learn that his purported saviour was in London. “What the hell happened? Didn’t you think the revolutionaries would discover the link to Canada? You should have run me out before the diplomats,” Copeland fumed.

“Sorry, it didn’t work out mate,” Sewell told him.

Copeland eventually escaped after his wife pulled strings with old friends in the new Iranian government. He died a decade later, having never directly addressed his wife’s growing suspicion that he had worked for the CIA. Despite the fact the Kiwis’ exfiltration effort failed, his son Cyrus is still grateful for the attempt. “I was impressed by Sewell’s bravery, frankly,” he told me. “And hugely appreciative that he was willing to do what Tony Mendez couldn’t, or wouldn’t. He threw my dad a rope during the darkest chapter of his life.”

5.Secrets and Lamb

Beeby and Sewell arrived in London on 5 February 1980. After they were formally debriefed at the New Zealand embassy, Beeby sat down and wrote a memo detailing how they had helped the Canadians and Americans. It was sent out to all New Zealand’s major diplomatic stations. “I remember reading it and thinking, ‘gosh’,” says Mattie Wall, who was then stationed in Kuala Lumpur. “My sort-of-loose understanding was that Chris Beeby had made the call — an independent call — to assist when asked to do so by his Canadian counterpart.”

Beeby and Sewell weren’t punished for the remarkable lengths they went to. That may be because the government tacitly approved of their actions. Speaking with Cyrus Copeland years later, Merwyn Norrish said Prime Minister Robert Muldoon had unofficially consented to Beeby and Sewell’s efforts. “We got the word: ‘Well, okay, but we didn’t tell you so . . .’”

Still, it took time for the shock of their experience to pass. “When they got back to London, he was not the Chris I remembered,” says Lynch. “He was quiet.” Beeby would eventually rise to the rank of Deputy Secretary of MFAT. He married three times and remained close friends with all of his ex‑wives.

Sewell was given a cushy desk job, then a sought-after posting to the New Zealand consulate in Los Angeles, where he was able to live openly as a gay man. After returning to New Zealand in the mid-1980s, he joined a communications firm in Wellington. He also found a partner: Grant Allen. In the few weeks he had left after his HIV/AIDS diagnosis, he finally came out to his staunchly conservative mother Joan.

Decades after his death, Allen discovered Sewell’s handwritten memories of driving Mendez to the airport. He consulted with a few of Sewell’s old diplomat friends, who recommended that Allen keep the notes private. Eventually, in 2013, Allen decided to donate them to the Alexander Turnbull Library.

It wasn’t just personal reticence that kept Beeby and Sewell quiet. MFAT made it clear it did not want the story known, in large part for trade reasons. “The New Zealand government never really wanted to claim credit because of the commercial relationship with Iran,” explains Mark. “It makes me so mad!” Copeland encountered similar difficulties while writing Off the Radar. “There were ‘sensitivities’, as one diplomat put it,” he explains. “I took that to mean a thriving trade relationship with Iran [which New Zealand] didn’t want to upset.”

The rescued Americans at the White House with US President Jimmy Carter. Photo: White House.

A former senior Beehive official at the time of the Iranian crisis speculates that then-Prime Minister Robert Muldoon “would have been actively involved in tamping the story down”. As he surmised, “With so many farmers in the cabinet and the National Party, Muldoon would have been terrified of being left with a heap of lamb on our hands.”

A similar caution persists to this day. Although New Zealand’s lamb exports to Iran collapsed when US trade sanctions were imposed on the country in the 1990s, they were revived in 2017 with a new trade deal between Wellington and Tehran, and that year, the value of our total exports to Iran reached $120 million. When I requested archival documents about Beeby and Sewell, MFAT declined to make the information available on the grounds that its release “would be likely to prejudice the security or defence of New Zealand or the international relations of the Government of New Zealand”.

Forty years on, there are few living witnesses from the New Zealand embassy during the time of the hostage crisis. Two months before I began reporting this story, some of Sewell’s closest friends threw out many of his personal documents due to a lack of storage space, including the text of Beeby’s eulogy. As Ken Richardson, the senior secretary to Minister of Foreign Affairs Brian Talboys during that period, told me, “You’re catching up at the end, just as people are rushing out the door.”

6.The Reunion

When Mark and Cora Lijek returned to Washington DC in the chill of the American winter, they were ecstatic to be home at last. But it turned out that it was not so easy to leave Iran behind them. With dozens of American hostages still in captivity, the mood in the US capital was funereal. The Lijeks tried unsuccessfully to get posted to the American embassy in Wellington, thinking that the relative sleepiness of New Zealand would be a welcome respite. Instead, Mark was assigned to Hong Kong. Undeterred, in mid-1980, he and Cora came to New Zealand for a holiday instead. When they stepped off their plane at Auckland International Airport, Beeby and Sewell were there to meet them.

The four set off in Sewell’s Ford station wagon for what turned out to be an epic tour of the North Island. At a restaurant in Rotorua, Beeby — wearing the jeans adorned with rows of belt loops — began flirting with a woman at another table. The two groups merged and Beeby started a limerick competition. His dirty rhymes plunged the table into hysterics. By the end of the night, Beeby had made such an impression that the woman invited Beeby, Sewell and the Lijeks to her house the next morning for a trout breakfast.

They rarely discussed their experiences in Tehran, Mark says. “Everyone wanted to forget about Iran because the hostages were still there.” But four decades on, the Lijeks emphasised their abiding gratitude to Beeby and Sewell. “I’ve always been curious about what crossed their mind about the potential consequences of helping us out,” says Mark. “They did what I hope I would do. I hope the US government would have been as willing to take a risk on behalf of a friend as they were.”

The Lijeks’ most vivid memory of that trip is of driving at dusk through the Bay of Islands, looking for a restaurant Beeby had read about in a magazine. “Richard was driving,” says Mark. “We kept going and going, and it got dark. And Richard was saying ‘There’s nothing here, you’re crazy!’ And Chris kept insisting, ‘No, no, no, here it is, I read this article: Panorama Seafood Restaurant’.”

Cora picks up the story. “As we continued up the road, there were fewer and fewer houses and no light. We didn’t think it existed. But all of a sudden we saw this light at the top of the road. And indeed there was this little restaurant.” Fifteen thousand kilometres from where they first met, the four of them sat inside on benches made from driftwood and ate freshly caught tuatua, friends bonded forever by a shared secret.

Pete McKenzie is a freelance journalist based in Wellington, where he focuses on politics, foreign affairs and legal issues.

This story appeared in the January 2022 issue of North & South.