This Old House

In which the author investigates his newly purchased home and discovers a rich vein of New Zealand history.

By John Summers

We bought just before Wellington went really crazy, but still things were bad enough. We had the experience everyone has now, of standing in a queue that stretched from front door to the street, seeing the same desperate couple at every viewing and knowing that they too were seeing a desperate couple wherever they went. Of course, the house we wanted was always out of reach or, if not, flawed in some way. Some were filled with asbestos, with borer, with roofs as structurally sound as a Cadbury Flake. At one, I watched two rats fight in the backyard. Another had been extensively renovated but nothing had building consent. It was all the work of an enthusiastic amateur. Walking down the stairs, I found myself forced into a strange, loping gait by steps built at a weird angle of the owner’s own design.

Eventually we gave in and bought what is termed a “doer upper” in real estatese, a “dump” in English. The windows were spongey in the corners, the walls and ceiling all battleship grey and the carpet the colour of cold porridge. The garage was in need of recladding and there was rust in the roof. I could go on and I have. Shortly after moving in, I began a list of all the things I needed to do but by the time I got to the end of page two I gave up, closed the document, never to open it again. Its title “House — To do”, a mocking presence in my documents folder to this day.

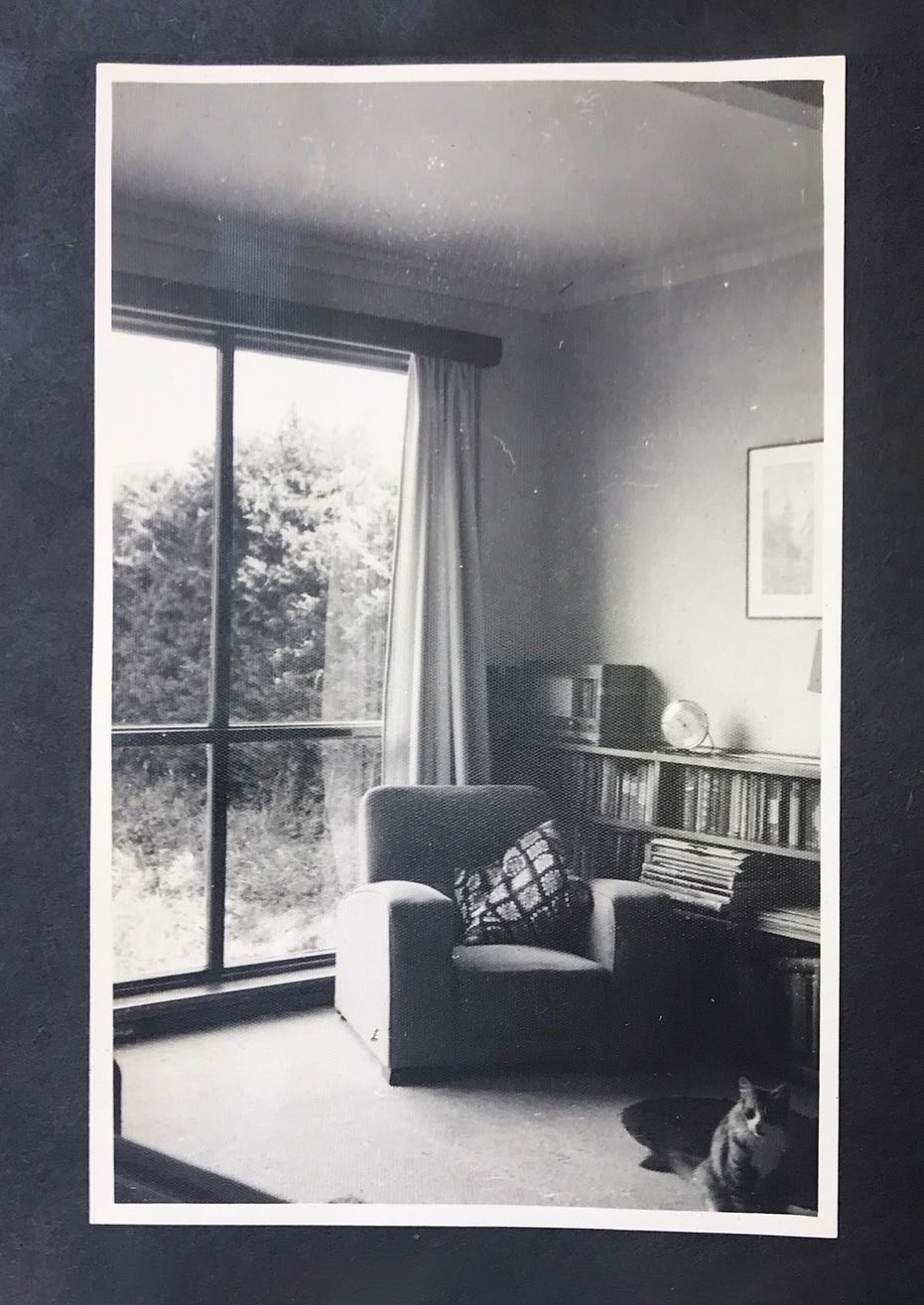

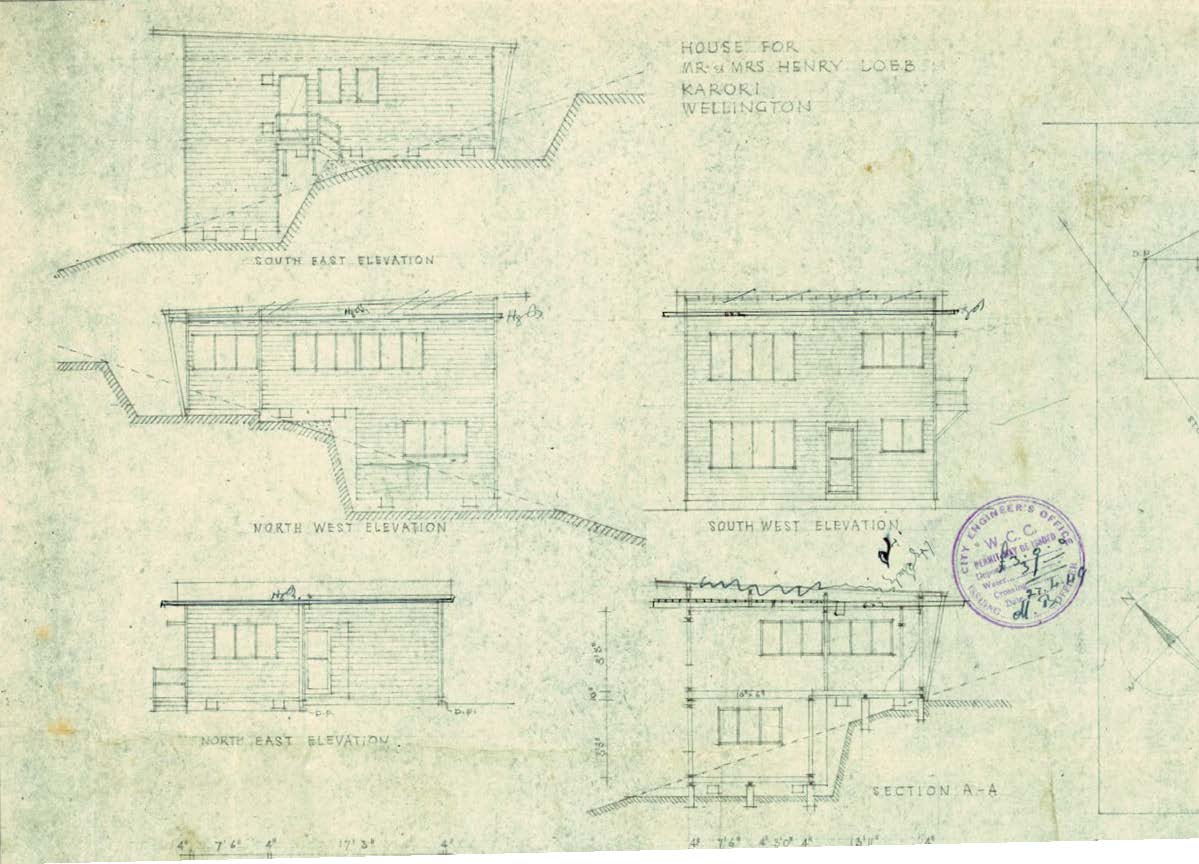

Still, for all these faults, there were things that we liked. This house was clad with black, rough-sawn weatherboards that gave it the look of something elemental, something of the bush and the dark trunks of the pongas that surrounded it. In the lounge and the downstairs bedroom there were windows that began at the floor and stretched almost to the ceiling. These seemed unusual for a house built, as this was, in the 1940s and I took them to be later additions. It was months after the purchase that, to check my theory, I paid the council $50 and they sent me copies of the papers in their archives, scanned pages of typewritten notes about drainage, requirements for joists and studs, and one hand-drawn plan in which the house appears as a rectangle of windows and weatherboards. This plan revealed that those windows were there from the very start, and the whole place originally had a flat roof. The peaked roof it has now was a later addition. Beneath this orderly drawing was the name of the architects responsible: Plishke and Firth.

The street front, 1949. All photos: Supplied.

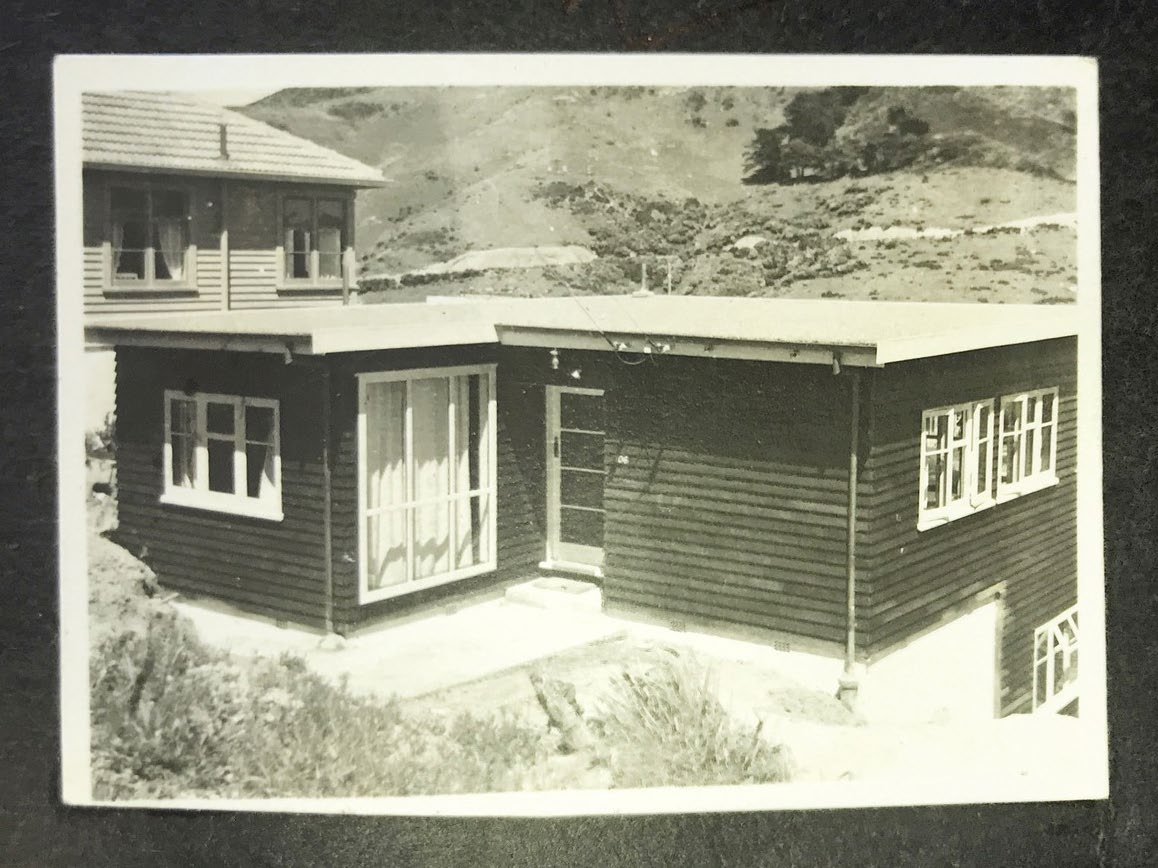

Ernst Plischke (he would eventually drop the ‘c’ to make his name easier for New Zealanders to pronounce) began his career as an architect in his native Austria. A kind of high priest of modernism, he enforced clean lines and careful proportions. References to the man tend to use the word “uncompromising” and photos show a stern set of eyebrows. He used glass liberally. One of his most famous projects, an employment office in the Vienna suburb of Liesing, was almost all windows. But by 1938, as Plischke approached the height of his powers, these qualities would count against him. The Nazis took Austria. Plischke’s work on a social housing project led by Jewish Social Democrats brought him under suspicion. Nor had the Nazis any love for modern architecture, preferring their own grandiose style that alluded to the glories of the Roman empire. The windows on that Liesing employment office were boarded over. The greater risk though was to Plischke’s wife, Anna Lang, who was Jewish. Remaining in the country was untenable. And so they cast about, considered the Philippines and other far-away places before settling on the one further than them all, New Zealand. Part of the attraction was surely this distance; another was the notion that this was a country waiting for inspiration. New Zealand was so isolated and so recently colonised, Plischke surmised, that the practice of architecture could only be in its infancy. There would be opportunity for him to make his mark.

Plischke got what he wished for, a version at least. He found himself working in the organisation that had arguably the greatest impact on the design of urban New Zealand: the government housing department. Although he had won critical acclaim in Austria, here he would be expected to start at the bottom. As a draftsman for the department, Plischke rendered porches for state houses. This was, depending how you look at it, New Zealand as parochial and insular, unable to see talent in its midst, or as egalitarian, a place where everyone pitched in and no one, not even the stars of Europe, could jump to the top. Eventually, though, Plischke would bristle and go into private practice — but again New Zealand insisted he go to the back of the queue. Our regulations required architects to pass a set of exams before they could practise here. Feeling this was beneath him, Plischke would have to partner with a New Zealander, Cedric Firth.

Although perhaps not as innovative as Plischke, Firth was also a modernist, with a particular interest in social housing. At one point he would take a job with the United Nations in New York, working on housing schemes for Brazil and Africa. Together Plischke and Firth were responsible for Wellington’s Massey House, our first glass-curtain-walled high rise, not to mention some of the most strikingly modern houses built in postwar New Zealand: spare and unadorned homes that sat, proud of their location, on hills or near bush, their rooms made purposeful with built-in furniture and bright by huge windows and sliding glass doors well before the ranch slider became de rigueur.

Some of this I have learnt from books and the internet, some from New Zealand’s Plischke expert, academic Linda Tyler. I emailed her on seeing those names on the plans, and immediately my phone rang. She told me that since writing her thesis on the man in 1986, she had regularly been contacted by people convinced that they’d found a previously undiscovered home of his design but it never turned out to be the case. She would examine those plans I had, noting the name of the original owner: a Henry Loeb. After some digging, she helped to put me in touch with Loeb’s daughter Trish Howes, one of the original residents of this old house.

Howes lives now in Sydney, retired after working as a family therapist. I called her one afternoon. She spoke with a slight Australian accent, and seemed to be pleased to be asked about her childhood home. I learnt that the room where my two-year-old son sleeps was once the bedroom she shared with her sister. And she told me about her father, whose story was like an echo of Plischke’s own.

The Langfords in the living room, circa 1950. All photos: Supplied.

Henry Loeb was born Heinrich Loeb in Austria, a member of a cultured Jewish family who later converted to the Lutheran faith — a ruse, Howe suspects. The father she knew was decidedly not religious. But if so, it was unsuccessful. I also exchanged emails with Trish’s brother, Stephen, who told me about his father looking into the window of his pastor’s house to see the man inside meeting with a Nazi. Austria was not safe. In 1938, a teenager still, Loeb and a friend, John Offenberger, fled to Denmark where they worked on a farm, a holding place. Their future would be changed by people in a far-off country: the University of Canterbury Students’ Association raised money to sponsor two refugees to come to New Zealand. Loeb and Offenberger were the chosen two. And so, Loeb’s became a New Zealand life. He studied here, would serve in our air force as a scientist tasked with treating tropical diseases, married a woman from Southland, Ngaire Head, whom he met at university, got a good job for Shell Oil and raised a family in Wellington.

Trish remembered going to Karori school and playing at the homes of neighbours. Her father dug the garden and touched up the creosote that kept the weatherboards black. Her mother managed the house, looked after the children. She hung the washing out on a rotary line. At the back of the section they burned rubbish in an old steel drum. Although very interested to learn about the architectural heritage of her old house, ultimately, she says, “It was always home. It represented what we were as a family. It was solid.”

Her grandmother, Ella, another refugee from Austria, also came to live with them. Back home she had been part of a family that knew wealth and high culture. They had a vault in a sought-after cemetery in Vienna, and in her youth she had been painted by her cousin, Otto Frederich, a contemporary of Klimt. In New Zealand, she took a job in a factory. Ella’s room is one I have recently renovated, peeling back old wallpaper to reveal an original layer that was peach-pink and embossed. It’s downstairs, this room, separate from the rest, large with a walk-in wardrobe where Trish says her grandmother hung her furs. Beside one of those floorto- ceiling windows she set up a small table and held bridge parties, serving her friends kugelhopf and other Austrian treats. Our spare room now, it was once the tiniest part of Vienna here in Karori.

These were pleasant memories mostly, tales of suburbia, the natural habitat of the father Trish knew. Listening to them, it was easy to think of his coming to New Zealand as inevitable. It was easy to forget there was a time when this was an undreamed-of future, the available paths dark and uncertain. 64,259 Austrians were killed in the Holocaust. Jews were sent to labour camps within the country where they were worked to death. Others were deported to ghettos in Poland and other occupied countries, or directly to concentration camps.

Present day with added deck. Photo: John Summers.

New Zealand did not present itself as an obvious alternative to these horrors. Proportionally, we accepted fewer refugees from Nazism than those countries we like to compare ourselves to, Australia, Britain and the United States. In Strangers Arrive, a book about the impact of European refugees on the arts in this country, Leonard Bell writes of a Czech who was granted a visa at the New Zealand High Commission in London in 1939 and told that 16,000 other applications had been rejected from that office alone. Walter Nash, our Minister of Customs over this time, held the perverse view that to turn away Jewish refugees was to prevent the rise of anti-Semitism in New Zealand.

The papers from the council showed Loeb as the original owner of the house, but they also revealed that, nine years later, when another bedroom was added, someone named Langford had taken possession. Loeb, I thought on reading this, didn’t stick around all that long for someone who’d had the house built. You may have already guessed the explanation, but I am a slow learner. Loeb was Langford.

Trish’s surname is Howes now, but it was Langford once and so was her brother Stephen’s. He told me his father once explained the name change as an attempt to avoid association with Leopold and Loeb, the pair of young murderers who inspired Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rope. But their crime dated to the 1920s. Anti- Semitism was surely the reason for the change, Stephen assumed, and so did Trish. It didn’t surprise me to hear this, but saddened me still, all the more so when I learnt what Langford had told his son. It suggested a need to shield his children and give them no cause for concern. Trish told me she never knew her father to talk of facing prejudice in New Zealand, which isn’t to say it never happened. She did describe times she had encountered attitudes that made her wince, but they all dated from a later period when the family returned for a time to Austria. A landlady there laughed on learning Winston Churchill had died, revealing her sympathies. More chilling were the things her father heard from his workmates. “He experienced colleagues, when they’d had a few drinks, coming out and saying really ghastly things about the roles they’d had in concentration camps. Their delivering of the gas. It was never very far away if you scratched the surface a bit.”

Bell’s book describes a common narrative about émigrés like Loeb, one I latched on to as I began my research into this house. European refugees, Bell wrote, “were either ahead of dominant local thinking or stimulated nascent cultural developments”. He cites Fred Turnovsky, a refugee from Czechoslovakia who described his fellow forced migrants as the “yeast that makes a society interesting”. I imagined this as I thought it must apply here: Langford bringing the sophisticated ways of Europe to a New Zealand that was backward and provincial. The house was the only evidence I had for this, but this was how many of Plischke’s clients were described. Like Langford, they’d found themselves here, not necessarily by choice, and refused to be constrained by local tastes. Plischke was an advocate for what is known as International Style, an architecture that, as the name suggests, looked outward, eschewing regional styles and nationalism. In this imagining of mine, Langford was drawn to Plischke, the fellow Austrian, for these very reasons, building a house that was an enclave of another, more cultured world.

Ernst Plischke as a young man. Photo: Private collection, Auckland. Right top and bottom — Back of the house / Street view, circa 1949. Photos: Supplied.

But I found myself, if not wrong, not quite right either. My version was too crude an application of what Bell discussed. After looking over the house, Tyler came to think it was more likely the work of Firth, the New Zealand partner in the firm. Plisckhe had built only one house with black boards like these. It’s a style that some say is characteristic of New Zealand modernist homes — the kind of regional architectural choice that Plischke resisted. “I think he felt pretty much a Kiwi,” Trish said of her father. “He had no evidence of an Austrian accent, not a shred.” He had changed his name to fit in and almost never spoke of the past. He adapted. She recalled him arguing often with Ella, his mother, a woman who remembered him as Heinrich Loeb, her ‘Heinsie’, a 17-year-old in Austria.They had reunited here, on the other side of the world, but now Heinrich was Henry Langford and seemed to have little time for preserving the ways of old Austria, too busy striving to make a life in this new place.

And yet Langford did not forego his identity entirely. “He was eager to keep a connection, a European connection,” Trish said. In his years here he was known to have that un-New Zealand quality, dressing well. He wore black tie to company balls, and he had, after all, hired a firm of architects to design his first home, so that it stood out, flat, black and boxy among the state houses. That he may have chosen a New Zealander over an Austrian for this unusual design seems like further proof of this to-and-fro of immigrant life, the forever deciding what to bring, to take, to leave behind.

Trish told me that on her last visit to New Zealand, years ago, she stopped by the house and was sad to see the place so rundown. It was depressing too, for me, to find home ownership quickly turn into weekends of DIY and invoices from the builder. Discovering the house’s backstory became a kind of reassurance, something to hang on to — the reason, I’m sure, that I’d been so keen to imagine Plischke, the more glamorous of the two partners, as the designer, creating something distinctive. But as the months passed, its history, although interesting still, began to feel less vital. The house had seen so much change, had been chopped about, a whole room added. The 90s in particular had left their mark — there were a number of aubergine feature walls. It was no longer Loeb’s or Langford’s, nor Plishke and Firth’s anymore, but ours. I hurried to make it a home for us, painting over the walls and fitting insulation beneath the floor of two cold rooms. I watched my son learn to walk on its floorboards. And as I did I read news stories about house prices that rose and rose, this whole city becoming one where few could afford to live. I despaired at this, and yet it gave me another way again to think of this place. A home, a history, it could also be a life raft. Yes, it was rickety and the temptation had been to let it float by and wait for another, but thank God I hadn’t. We have a house, are lucky enough to say that. We’re raising our son here and, on a rainy night last November, it became the birthplace of our second. This home is the first he will ever know.

Elevations from the original plans to the house. The large windows were characteristic of Plischke and Firth’s work. Image: Supplied.

John Summers is a contributing writer to North & South and author of The Commercial Hotel, an essay collection.

This story appeared in the March 2022 issue of North & South.