Culture Etc.

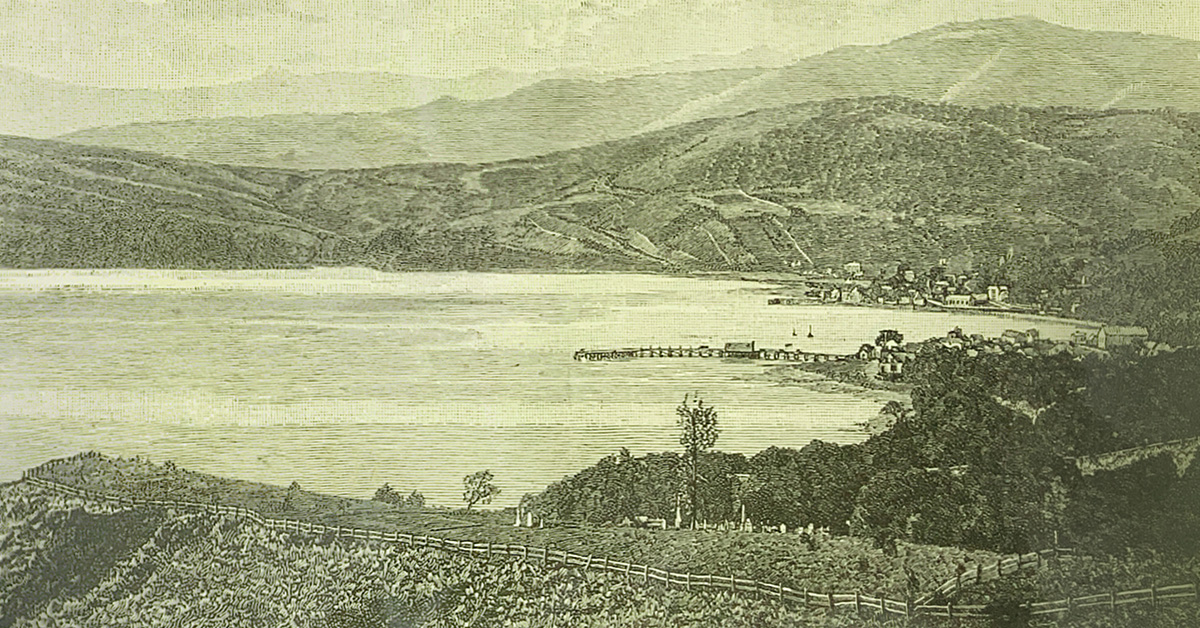

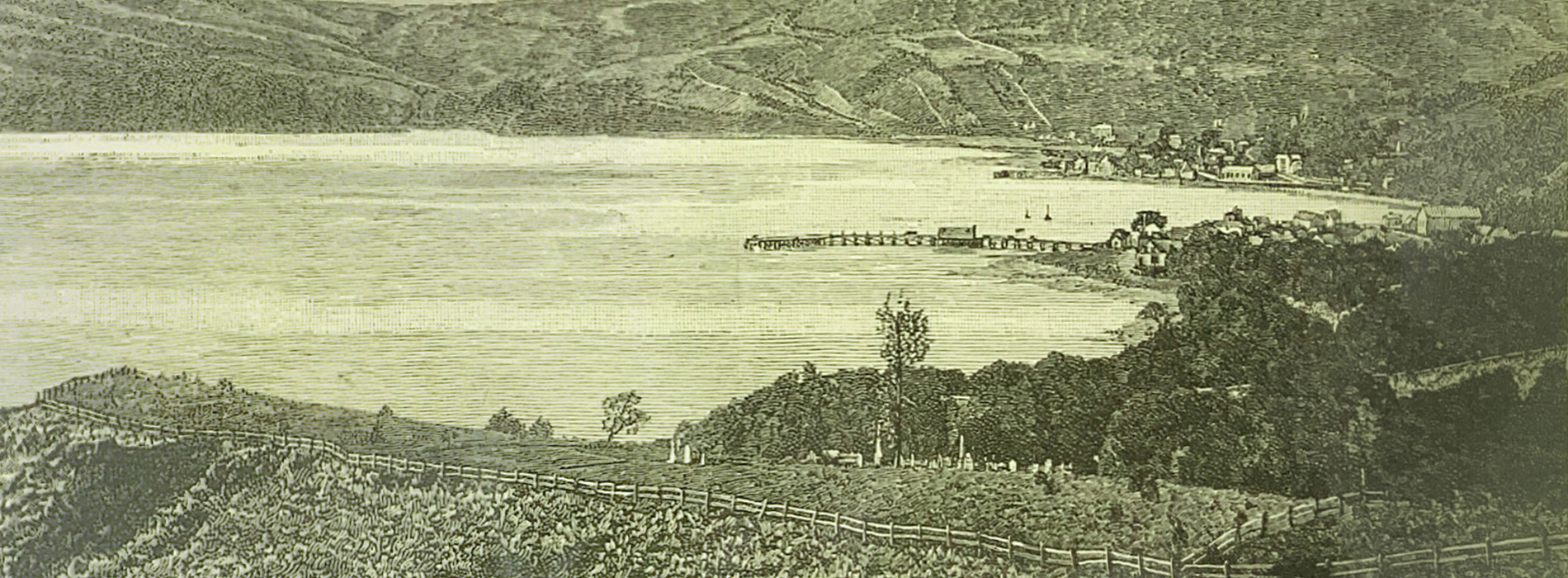

Above: Early etching of Akaroa, date unknown. Image: Supplied.

About Town: Akaroa

One of the only places in the country with an overtly French influence, this harbour town is alive with memories of love and romance.

By Tom Augustine

Akaroa Cemetery is built on a sloping hill, with tall pine trees framing a view of ethereally blue water, the peaceful bay around which the town is built. There’s a road nearby, but cars rarely pass. Most of the time the only sound is the birdsong and the swaying of the trees. I’ve always thought there would be few better places to spend eternity.

For my 30th birthday, my girlfriend Amanda gave me an intricate framed print of Akaroa township in the 1890s. Looking at it for a moment, I realised that there, etched in the foreground, was the beginnings of the cemetery — the place where many years later my grandparents would be laid to rest overlooking the harbour. Amanda hadn’t realised the significance when she bought it. It felt like some kind of spiritual serendipity.

Akaroa is my family’s hometown, and our roots there go deep. Famously Canterbury’s first town, it was settled by the French in 1840. The influence lingers in streets with names like Rue Jolie and Rue Lavaud, the French dining establishments, and the way its cottages, alleyways and avenues evoke the back streets of some Old World riviera. The French arrived on two ships, L’Aube and the Comte de Paris. The latter carried settlers, the other was a warship. They landed shortly after the British and iwi leaders signed the Treaty of Waitangi, cementing the Brits’ foothold in Aotearoa — and yet Akaroa remained “the French town”. I asked my Great-Uncle Leo, who turned 95 in February, about his memories of growing up alongside the children and grandchildren of those original L’Aube settlers. If there was animosity between the French and English in the region, he never noticed it.

Akaroa sits to one side of a deep inlet nestled in the caldera of a long-extinct volcano — the name translates to “long harbour”. Further down the harbour, outside of the town proper, is Ōnuku, a small Māori settlement with an historic church and marae. An iconic red-and-white lighthouse used to shine out from the harbour’s eastern head and now, relocated, tips the headland by the cemetery. My great-grandfather John Prendergast was the town’s postmaster, living there with his wife, my grandmother’s mother Esther, in the 1930s. They had six children including Uncle Jack, my great-uncle, who ran the Akaroa Mail for many years. If there was news to share, he was the only one around for miles with a paper to put it in.

My mum’s earliest memories are of this place, although by then she and her family (mother Esther, named after her own mother; father; brother; and three sisters) lived elsewhere, only visiting Akaroa for holidays. Mum remembers legendary, vomit-on-the-side-ofthe- road car trips over Akaroa’s hectic, twisting hills in the days before seatbelts, the bassinet of her youngest sibling Ginny unrestrained in the back seat. She and her siblings would spend hours playing in the Garden of Tane, a lush stretch of dark green forest with a maze of walking tracks. My mum often talks about hearing the “call” to go back to Akaroa, year in and year out. I’ve started to hear it too; it sounds like quiet, and empty schedules.

My grandparents’ budding romance was, by all accounts, grist for the local rumour mill: the outsider courting the postmaster’s daughter in a thrilling will-they-won’t-they.

As you head towards Akaroa Harbour, driving around the hilly country roads which wrap around the valley, it feels like slowly sinking into the arms of a loved one. You turn a final corner as you enter the town, the main drag revealing itself in quiet splendour. The 19th-century buildings dotting the streets are largely intact, as is the tiny Catholic church sitting at the top of a grassy hill. There’s the beach where folks wander after dinner, and boats bobbing on the surface of the glassy harbour waters like resting gulls. The last time I was there, in a rental car, the Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place” kicked in on the car speaker as we turned onto the main street. Home, it’s where I want to be, but I guess I’m already there . . .

My favourite time to visit is in the dead of winter. Unlike other winter holiday spots, Akaroa isn’t a skiing town, so there aren’t too many people around — which suits me just fine. In the isolation I feel like I’m speaking to the place, and it’s speaking back. It’s not as if it has a great array of tourist attractions to set it apart from other places. There’s the famous dolphin cruise, where you can spend a day spotting albatrosses and Hector’s dolphins in the bay; the Giant’s House, a strange and delightful garden featuring massive mosaic sculptures — a wizard, an angel, a full jazz band; or Barrys Bay cheese factory just over the hill (a must, I reckon — their Canterbury Red cheddar is something special). But what truly makes the town is the feeling. It’s waking up in a little apartment on a cold morning, drinking coffee and looking out at sheets of rain on the grey-blue harbour. When a southerly brings with it crisp blue skies, it’s taking a morning walk along the wharf or through the township, stopping at the boulangerie or the crystal shop.

I’m reminded of the films of Éric Rohmer, director of masterworks such as Claire’s Knee and The Green Ray, when I wander through Akaroa — and not just for the French connection. The laconic, delicate cosiness of the place lends itself unmistakably to spending time with a loved one while not really doing much at all, the way the gorgeous, lovelorn types in Rohmer’s films tend to spend their days. My grandparents met and fell in love here, seemingly by a stroke of luck. My grandad John, a schoolteacher, was assigned to teach in Akaroa as part of his required country service. My grandma Esther lived on Rue Jolie. He would push her bike home from work for her. Their budding romance was, by all accounts, grist for the local rumour mill: the outsider courting the postmaster’s daughter in a thrilling will-they-won’t- they. They got married at the little Catholic church, St Patrick’s, where Uncle Paul, a priest, would later commemorate his 40th year as a member of the church. My grandparents were together for 50 years, their love the rock of our family. If I believe in any sort of spirituality, it’s the feeling of their presence in that place, the way their memory seems to roll over the hills the way the descending sun does at the end of the day.

I took my girlfriend there the first year we were dating, in the middle of winter. It was freezing cold, but Amanda didn’t mind. We had only been together for a short while, and I remember some exclamations of “Going away so soon?” from well-meaning friends. It just felt right. She fell for the place immediately, and I fell further for her. On one of the last days of our trip we went to the cemetery where just a few years prior my family had buried my grandparents’ ashes side by side in the same plot, overlooking the ocean through that gap in the trees. Amanda asked to spend some time at the grave by herself. I watched her speaking to their headstone from a distance. I’m not sure what she said to them. I was just glad she was there.

I come home, she lifted up her wings / I guess that this must be the place . . .

Tom Augustine is a writer and filmmaker. He thanks Leo Prendergast for his help on this piece.