Four Corners

Flagging Concerns

Why the use of two instantly recognisable Māori flags at the Parliament protest was so jarring to see.

When black smoke rose from Parliament lawns on 2 March, two flags usually reserved for Māori sovereignty movements flew from tall white poles. On the ground, police had donned riot gear, protestors threw bricks, and the area was strewn with remnants of three weeks of occupation — some of which was now ablaze. Wellington’s wind lifted Te Kara o te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tireni — the flag of the United Tribes — and the tino rangatiratanga flag in scenes of chaos broadcast here and across the globe. Both flags are powerful symbols defined by historic circumstances — which in this context seemed completely absent.

In fact, flag historian Dr Malcolm Mulholland (Ngāti Kahungunu) believes their use showed an historic amnesia: “To align that protest with the struggles of Māori, relating it to the Treaty and notions of sovereignty, was convoluted.” Mulholland, a senior researcher at Massey’s Te Pūtahi-a-Toi School of Māori Knowledge, says the flags were appropriated and misused at the protest. “Anybody who knows anything about Covid-19, pandemics, and how they affect Māori would know that the bigger picture, and protecting the health of others, is far more important than the restrictions.” When he saw the flags there, alongside white supremist signs and symbols, Mulholland was aghast. “My God, our ancestors would turn in their graves.”

It isn’t the first time use of the tino rangatiratanga flag has been criticised from within Māoridom. In 2009, Linda Munn (Ngāti Manu, Tauranga Moana), one of three artists who designed the flag in 1989, spoke up to protest its use by “groups [who] would do stuff that was anti-social, bad manners”. She wanted the flag’s origins to be remembered and respected, telling Mana magazine in her first interview about the flag in 20 years that she thought people had forgotten its symbolism. The tino rangatiratanga flag was designed following a nationwide competition held by Te Kawariki, an activist group, which wanted to create a national Māori flag to represent pride and identity. It was intended to be used for kaupapa Māori purposes, born out of a movement fighting for Māori sovereignty and collective wellbeing.

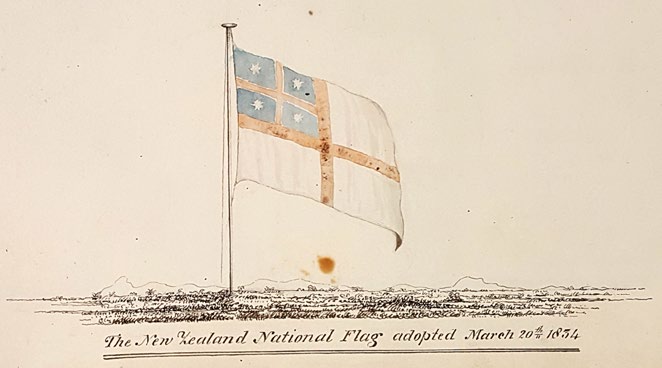

Te Kara o te Whakaminenga o Nga Hapu o Nu Tireni, drawing by Nicholas Charles Phillips of the HMS Alligator, 1834.

Munn spoke out again last November after seeing the flag flown, sometimes upside down, in anti-lockdown protests. Speaking to Māori Television’s Te Ao, she was clear: “It should never fly next to something as disgusting as a Trump flag.”

Hilda Halkyard-Harawira (Ngāti Hauā, Te Rarawa) is an activist from “way back”. A member of Te Kawariki, she helped conceptualise the flag competition that birthed the tino rangatiratanga flag, and she has been advocating against racism and Tiriti breaches since 1979, when she was involved in what’s often referred to as the “haka party incident”, a protest against an annual performance of Ka Mate by engineering students at the University of Auckland which Maori students had long said made a mockery of their culture. While she’s “yelled a few things in my time”, Halkyard-Harawira could not get on board with the protest in Wellington. “There was a whole lot of jumbled messages,” she says. “For all the weeks they were down there, I couldn’t tell what their kaupapa was.” She was also concerned by presence of white supremacists and supporters of former US president Donald Trump at the protest. “They are not our allies . . . it bothers me when our flags are flying in the same company as those people.”

Munn spoke out again last November after seeing the flag flown, sometimes upside down, in anti-lockdown protests. “It should never fly next to something as disgusting as a Trump flag.”

Tino Rangatiratanga flag.

Halkyard-Harawira sees Te Kara o te Whakaminenga as the tuakana (elder brother) of the tino rangatiratanga flag. Te Kara was this country’s first national flag; it was flying when He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni (the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand) was signed in 1835. The second article of the declaration states, “we will not allow any other group to frame laws”. The protestors were trying to use the flag as a callback to the declaration to delegitimise the mandates and the government — by flying the flag, protestors are “climbing on board”, Halkyard- Harawira says. “It’s a concern when strangers to kaupapa Māori use our flags for their own ends.”

Much of the rhetoric at the Parliament protest was anti-establishment, anti-bureaucracy and anti-state. Some of it was directly imported from overseas. In an echo of Trump supporters in the United States, protestors carried signs saying “Fauci lies” — a reference to Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden and director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. They set up an online petition designed to hold him accountable for “lying about Covid-19”. Vexillologist John Moody believes protestors mimicked the similar protests in Ottawa where the US flag was prominent. (The Canadian flag appeared too, sometimes upside down, as did the flags of Bolivia and Romania.) Te Kara o Te Whakaminenga is foundational to our nationhood, he notes, but was here “being used as a flag of a parallel state”. Through these visual cues protestors claim to be distressed patriots, framing their actions as “fighting for the country”, in order to justify chaos. Moody believes that less savoury elements in the movement can, in effect, hide behind the flag in order to give them some sort of credibility.

While Halkyard-Harawira believes Māori flying Te Kara o te Whakaminenga there were kuare — unaware, uninformed, held in no esteem — she worries New Zealand-based Trump supporters will “run off with our flag and our concepts to justify themselves”. She is wary of their misappropriation of the flag: Trump advocates an ‘America First’ imperialism but the very reason the flag came about was to claim sovereignty for Māori against imperial encroachment. The governance structures set out by the declaration of independence “wouldn’t allow a new bunch of lawless Pākehā to subvert our sovereignty struggle for mana motuhake and self-determination”, Halkyard-Harawira says.

Māori have been fighting for more than 182 years for their rights and sovereignty. It’s a struggle that continues, with the movement working towards new, Māori-inflected constitutional arrangements for New Zealand.

Matike Mai is an independent working group that launched a report on constitutional transformation on Waitangi Day in 2016. The report was generated through a national consultation process, and facilitated by respected leaders Margaret Mutu (Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua) and Moana Jackson (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Porou). Halkyard-Harawira doesn’t know what the Parliament protestors, “those other fellas”, are planning now, but suggests that rather than steal symbols “they should come up with their own”.

The morning of 16 March was crisp, the sky a Wellingtonian shade of grey. About 200 people sat quietly in rows of chairs in the parliamentary grounds. The previous two weeks had been spent cleaning up after the protestors. There were no flags — the only pop of colour was the orange road cones on the bare lawn. Te Ātiawa Taranaki, mana whenua of the area, led a ceremony to restore mana to the land. “This is a time for reflection and understanding. It’s also a time for healing and hope,” Taranaki Whānui chair Kara Puketapu-Dentice said in a public statement. Fences remain around the playground and lawns, and statues still bear graffiti. In June, when the grounds are fully restored, another ceremony will take place to reopen them.

The land was not the only thing the protestors degraded. Mulholland believes that, like the grounds, the flags’ mana could be restored with a ceremony. They could be flown again, on the same grounds, but with respect. He suggests appropriate representatives could speak to the public about their histories, their interpretations and the contexts they should be flown in. “The record could be set straight.”

Tino rangatiratanga alongside the flag of New Zealand

Waitangi Day, Auckland 2012. CC By-SA 3.0

Gabi Lardies is a The Next Page intern, a role funded by NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.