You Have Now Entered Carbon Country

New Zealand’s climate policy is creating a dense forest of winners and losers.

By George Driver

1326-hectare Fairview farm in the Waitaki Valley was planted in pine trees as part of a permanent carbon forest about nine years ago. The neighbouring 2590-hectare property was also planted in pine this year. Photo: George Driver.

If Luka Love had held on to his Bitcoin, he would be a multimillionaire by now. Back in 2010, Love was a 25-year-old university dropout living in Melbourne. A friend sent him a white paper by a mysterious web developer known as Satoshi Nakamoto that outlined how a new digital currency could transform trade on the internet. “I thought it was brilliant,” Love says. Back then, you could purchase 12 Bitcoins for a dollar, and soon Love was buying crypto and spending it online. Alas, despite his foresight, Love didn’t hold on to a single “coin”. If he had, he could have sold just 12 Bitcoins when the price peaked at $90,00 last November for just over $1 million. “I kind of kick myself now that I didn’t hold on to it,” he admits.

Love has dabbled in other investments since. After earning “crazy good money” at a recruitment company in Australia, he lost a chunk of it in managed funds in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. Then he missed the next big bubble: housing. Now 37 and studying an honours degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Waikato, Love says he’s priced out of home ownership. But he may have finally got in at the right time for the next bull run.

About three years ago, Love met economist and then-leader of the Opportunities Party, Geoff Simmons, who explained to him the concept of New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). “It struck me as a bolt out of the blue,” Love recalls.

Luka Love is one of a growing number of people investing in carbon credits via the New Zealand stock exchange. Photo: Supplied.

The ETS is the country’s main tool for meeting our climate change targets. It works by putting a price on greenhouse gas emissions (although methane produced by farm animals, which accounts for nearly half of our emissions, isn’t currently included in the scheme). For every tonne of greenhouse gas a company emits, they have to buy and then surrender an “emission unit”, commonly known as a carbon credit — basically a permit to pollute.

The obligation falls at the highest point in the supply chain — mostly oil and coal importers, coal mining companies, gas producers and steel mills — who pass on the cost to the rest of us. On the other hand, those who plant trees can earn credits from the government and sell them to polluters. And anyone can buy or sell carbon credits, just like purchasing shares on the stock market.

Captivated by the prospect of helping to fight climate change and hopefully making some money at the same time, Love’s investment brain began turning. Using an app on his phone, he bought into a fund traded on the New Zealand stock exchange (NZX) based entirely on carbon credits.

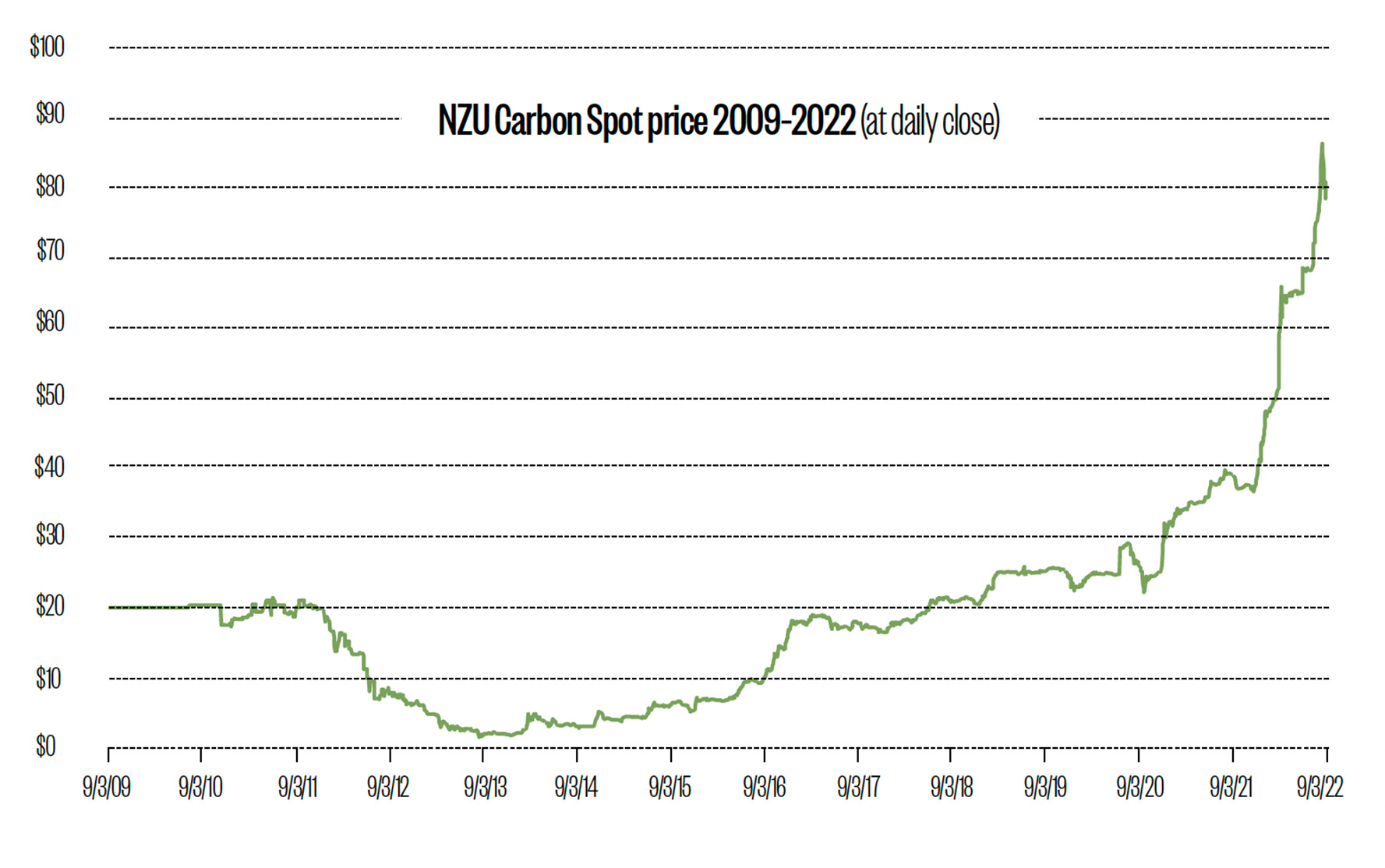

Like cryptocurrency, it seems a strange investment at first. But in the past year, the value of carbon credits has more than doubled. After over a decade in the doldrums, a single credit jumped from $37 at the start of 2021 to a high of $86.25 in February this year. “It has blown up,” Love says of his investment. “It’s been crazy to watch.”

Almost no one expected this to happen. Until recently, the ETS has been little understood and, for most people, was easily ignored. But lately investors and speculators — like banks, energy trading houses, investment funds and Luka Love — have been snapping up carbon credits, betting the price will keep rising so they can sell up and cash in. And the ripple effects can be seen in the New Zealand economy, the atmosphere and even the landscape, as landowners coat the country in pine trees, potentially for centuries. The winners and losers of the country’s climate change policies are beginning to emerge.

At 9am on 17 March 2021, James Shaw rang the bell at the New Zealand stock exchange, kicking off the country’s first carbon credit auction. The besuited climate change minister in the epicentre of the country’s finance industry was a fitting image for how New Zealand has opted to bring down its emissions: by relying on the market forces of supply and demand.

This wasn’t always the case. When the ETS was first established in 2008, the government set a price cap on carbon credits. It was initially $25, enough to add a mere six cents to a litre of petrol. Emitters could buy an unlimited number of credits for that price, and they could also purchase credits from forest growers and from overseas. Then that market price plummeted. In the early 2010s the market was flooded with “junk” credits of dubious integrity from Russia and Ukraine, causing the price to plummet to a record low of $1.45 in 2013.

After the trade in overseas credits ended in 2015, the price slowly rebounded, but the $25 price cap remained. By 2018, a Productivity Commission report declared the ETS had been “ineffective in inducing significant emissions reductions”. This was an understatement: emissions hadn’t budged at all.

Last year, the government embarked on a fundamental overhaul of the scheme, dropping the fixed price. Instead, emitters would have to compete for a fixed pool of credits sold at government-run auctions four times a year. The pool would shrink annually in line with our climate change targets, setting the stage for prices to rise.

The government did retain a degree of control to prevent the price from going too high too fast. If that happened, businesses wouldn’t have time to adapt to greener alternatives and would have no choice in the short term but to buy credits and absorb the cost or pass it on to consumers. So the auctions include a price ceiling. If the price of a single credit went above $50, the government could flood the market with up to seven million credits to stabilise it. The ceiling was designed to ensure prices “do not reach a level that would have a severe negative impact on households and the economy”, according to a consultation document, and should be set so high that it will “be used rarely, if at all”. In the event, the price ceiling was breached by spring.

At the first auction in March the price cleared at $36. It bounded up to $41.70 at the June auction and then in September it blew through the $50 ceiling. The government flooded the market with all of its seven million credits, but the auction still settled at $53.85. At the time, AUT climate change researcher David Hall called this result “deeply problematic”. The ETS price wasn’t behaving as expected, he said, with speculative behaviour potentially behind the spike. “It’s just got more and more complicated.” At the final auction of the year, with no controls left in the tool box, the price reached $68.

Then the carbon price kept rising. The ETS had been given teeth.

At 4am on 4 October 2020, Murray Simpson awoke to the phone ringing. When he picked up, his neighbour told him to look out the window. A wall of flame 30 metres high was ripping through the pine forest beside his farm, lighting up the night with a ghostly orange glow. “I thought we were going to be wiped off the face of the earth,” Simpson says.

The 68-year-old is a fourth-generation farmer and looks it: almost two metres tall, dressed head to toe in Rodd & Gunn and with a build suited to knocking in fence posts. He had been farming for 45 years at Balmoral, a 5000-hectare sheep station in rolling tussock country on the southern flank of the Waitaki Valley. Simpson had farmed a mix of cross-breeds and merino, changing the ratio as the market for fine wool rose and collapsed over the decades. But then a different kind of farmer came along.

Nine years ago, a company called New Zealand Carbon Farming bought the neighbouring property, Fairview, and planted its 1326 hectares in Pinus radiata. These trees will never be harvested. They are being grown not for their timber, but for carbon credits.

Radiata is the favoured crop of the carbon farmer — it’s cheap to plant and grows quickly and just about anywhere, so it earns credits faster than any other tree. A decade-old hectare of pine will have sequestered up to 296 tonnes of carbon, while a hectare of natives will have sequestered about a third of that.

Simpson says the first problem he encountered from his new neighbour was pests — as many as 30 deer a night coming out of the forest and feeding in his farm. He had to put up a deer fence to keep them out. Later, he worried about water. The forest is planted on major tributaries of the Kakanui River, and Simpson believes the trees will suck them dry, affecting the river’s flow and the farmers that rely on it for irrigation downstream. Some studies have found planting pines can cut water flows by up to 80 per cent.

Then the fire came. On a windy night, a tree fell on to power lines and started a blaze which quickly swept into Fairview forest. Simpson says there were no firebreaks to slow the inferno, and by 5am the flames had reached his property, burning down a shed filled with farm machinery and inching towards the family home. He and his wife took their wedding photos and fled.

“These forests are going to look like the scene of a Mad Max movie,” says Waitaki farmer Jane Smith.

Fortunately, the local fire brigade managed to bring the blaze under control before it engulfed the house, but the landscape was scorched. When I visited Simpson in February, Balmoral was still bordered by blackened trunks. The fire destroyed about half of the Fairview forest. Some of the burned trees were felled and replanted, but elsewhere new seedlings have simply been dug in between rows of charred and skeletal trees. “There’s plenty of fuel there now for the next fire, and there will be another one,” Simpson says. “It’s only a matter of time.”

About six months after the fire, Simpson discovered the 2590-hectare sheep and beef farm on the other side of his property, Hazeldean, had also been sold to New Zealand Carbon Farming. He would be surrounded by permanent forest. The pine seedlings at Hazeldean are already in the ground — little green stems poking up through golden tussock. “You’re never going to see this landscape again,” Simpson tells me. “It will be altered forever. It will take god knows how many hundreds of years if it is ever able to revert back.”

Simpson sold his property last year, moving to Ōamaru, where he says the constant traffic keeps him on edge. He’s embarked on a campaign to stop more of the countryside disappearing under a blanket of pine. “I just don’t want people to come to me in 10 years’ time and say, ‘Why didn’t you tell us what was going on?’”

The ETS was designed to encourage tree planting — and for good reason. Forests will play a pivotal role in helping New Zealand meet its climate change targets. In 2019, they reduced our net emissions by a third, and to further offset our emissions the Climate Change Commission recommends we plant another 380,000 hectares of exotic forest (and 300,000 hectares of native forest) by 2035 — an area more than twice the size of Rakiura Stewart Island. As the price of carbon climbs, the incentives for planting trees have increased substantially.

Permanent exotic forests are the most profitable way to earn carbon credits. If the forest is harvested the bulk of the credits have to be surrendered to the government, accounting for the emissions released when the trees biodegrade or are burned. If the forest is never harvested, then it can earn credits for decades more. And every credit can be sold for a profit.

As the carbon price has soared, this kind of carbon farming has become more profitable than traditional farming in many parts of the country. A recent government consultation report found that permanent exotic forests provide higher returns than production forestry and “significantly higher economic returns than sheep and beef farming”. If the carbon price reached $110, the report noted, carbon farming could become “competitive with lower productivity dairy land”.

Farmers, investors and foresters have taken note. Last year, a report commissioned by Beef + Lamb New Zealand estimated a third of whole-farms sold were going into permanent carbon forests — and that’s before the carbon price jumped. A Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) survey of major foresters found the amount of exotic forest they planned to plant nearly doubled between 2019 and 2021, to 45,300 hectares. Almost a quarter was slated for carbon farming. Meanwhile, native plantings have been languishing, with foresters planning to plant just 700 hectares of “tall indigenous trees” and 5100 hectares of mānuka last year.

No other emissions trading scheme in the world includes incentives for forestry like we do, where growers can earn unlimited credits. Forestry isn’t part of the European Union’s emissions trading scheme at all. And this anomaly appears to have attracted the interest of overseas investors.

In 2018 the government introduced a “special forestry test” allowing overseas buyers to purchase sensitive farmland without having to prove it will benefit New Zealand — a requirement when buying sensitive land for other purposes. By the end of 2021, according to figures provided to RNZ, 212,346 hectares had been sold to foreign buyers. An Austrian countess snapped up a station near Masterton to convert to pine. Swedish multinational furniture manufacturer Ikea secured a 5500-hectare sheep and beef farm in the remote Catlins, while German insurance giant Munich Re bought large parcels of land near Gisborne and Southland. In the year after the changes were introduced, the price of North Island forestry land doubled.

In 2020, about half of Fairview forest in the Waitaki Valley was burned and new seedlings have been planted between blackened trunks. Photo: George Driver

The special forestry test supposedly applies only to land bought for timber production. But some experts predict that by the time the trees are due to be harvested, in about 30 years, those rules won’t be enforced and the trees will be left standing. Lincoln University emeritus professor Keith Woodford says some of the land in question appears too steep for harvesting the trees to be economic, and suspects it is being bought purely for the carbon credits.

A diverse range of groups, from Forest and Bird to Federated Farmers, have raised concerns about what will be lost as more of the country is carpeted in pine. Some rural communities believe they are facing an existential threat — there aren’t many jobs in a forest that’s never chopped down. One report estimated that 83 per cent of Tairāwhiti’s grassland could go into permanent carbon forestry, potentially putting 10,000 jobs at risk.

Then there are the environmental effects. Environmental Defence Society CEO Gary Taylor says exotic carbon farms will “be a mess for over 150 years” as the trees grow and fall over, which will “degrade landscape values at an industrial scale”.

“These forests are going to look like the scene of a Mad Max movie,” says prominent Waitaki farmer Jane Smith. “It’s going to be a toxic legacy.”

The other fear is that the ETS won’t lead to actual emissions reductions — that large emitters will simply plant more trees to meet their ETS obligations instead of reducing their reliance on fossil fuels. Already some of the country’s biggest emitters — Air New Zealand, Contact Energy, Genesis Energy and Z Energy — have formed a company called Dryland Carbon which plans to acquire 20,000 hectares to plant in forest over five years. In 2020 it got approval to plant a permanent pine forest of one million trees south of Gisborne.

Last year, the Climate Change Commission warned about these distorted incentives, predicting that the ETS could prompt more planting of pine forests than we actually need. It recommended the government revise the regulations by the end of this year.

The government is now making a move. In March it announced it was considering banning exotic forests from earning credits under the permanent forests category of the ETS (with a possible exception for those that transition to native trees). The rules for overseas forestry investment are also tightening up. In late February, the government announced the “special forestry test” would no longer apply to conversion projects: investors will have to prove that their purchase of land they want to plant in trees will benefit the country, just as they would if they were buying other sensitive land.

But these measures may be too late for some. No one expected the price of carbon to rise so fast.

Farmer Murray Simpson has been calling for carbon farming to be regulated after a pine forest beside his property set fire. Photo: George Driver.

In March, using an investment app on my phone, I searched for “CO2” and came to the Carbon Fund, an investment entity listed on the NZX that consists almost entirely of New Zealand carbon credits. Using a free sign-up offer and a $5 credit, I effectively bought a share in a carbon credit. With the swipe of my thumb, I’d become a speculator in the ETS.

When the Carbon Fund launched in 2018 it was apparently the first of its kind in the world. It attracted modest interest at first, but by March this year its market capitalisation was just shy of $100 million.

Quintin Tahau, who manages emsTradepoint, a natural gas and carbon credit trading platform run by the state-owned electricity transmission company Transpower, estimates that speculators make up about a third of the carbon market. These include major investment companies and global energy traders.

“International trading houses, who are massive, are showing lots of interest in the New Zealand carbon market,” Tahau says. “If you look at what the price has been doing in New Zealand in the past year you can see why.”

In 2018, the Productivity Commission said the carbon price would need to be between $30 and $80 by 2030 if we were to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. The price already passed $80 in February. In an attempt to explain the rapid increase, some have pointed their finger at speculators. Last September, RNZ reported the scheme had been “hit by speculators eyeing up easy money”. Keith Woodford wrote the government was being “outgunned by institutional investors” at the carbon credit auctions and that “some of New Zealand’s biggest companies are playing the game”.

In any case, Tulloch argues that some investors provide a genuine service. Banks and other institutions provide forward contracts to emitters to help them lock in a carbon price for future obligations.

Speculators also help the market to function efficiently, he says, by increasing the number of buyers and sellers. Only 277 companies have to buy credits in the ETS and the country’s five oil importers account for almost half of the mandatory market.

Ivan Diaz-Rainey, an associate professor of finance at University of Otago and founder of the Climate and Energy Finance Group, which researches carbon markets around the world, believes speculators “are definitely playing a role” in the price spike. He explains that speculators have been buying up a range of commodities that might increase in value as businesses take action on climate change, including carbon credits. But he doesn’t see that as a bad thing — at least not yet.

“Carbon was just horribly undervalued for a long time,” he says. “If you get carbon prices of $200 then you might start to worry whether it’s being driven by fundamentals, but right now I think it’s good that prices are increasing. There’s starting to be strong incentives to decarbonise.”

According to MFE, a carbon price of $75 should provide an incentive to cut emissions from electricity generation by more than 70 per cent as coal becomes uneconomic. Genesis Energy is already set to trial biofuel at the country’s only coal power station in Huntly. At $60, it should become cheaper for dairy processors to burn biofuel instead of coal in boilers.

Despite the carbon price doubling last year, it’s still only a small factor in the rising cost of living. At $80 a unit, the ETS adds about 20 cents to a litre of fuel. Overall, Treasury estimates that a carbon price of $75 adds about $6.80 a week to the expenses of a middle-income household. But if the country is to meet its target of net-zero emissions by 2050, the price will need to rise much further: the Climate Change Commission says a price of $130 will be required by 2030 and $250 by 2050.

Matt Walsh and Bruce Miller are unlikely farmers. Their experience mostly comes from working in air-conditioned office blocks, rather than wool and dairy sheds. But together, they manage more land than probably any other farmer in the country.

Miller’s pathway into farming started with a career in banking, as he worked his way from National Bank in Hamilton to trading commodities and derivatives at Bankers Trust International in London in the 1990s. When he returned to New Zealand he was involved in some of the country’s first carbon credit deals while working for energy generator and retailer Mercury.

Walsh, meanwhile, spent more than two decades working with tech and telco start-ups in New Zealand and Silicon Valley before coming up with a new idea: starting the country’s first carbon farming business.

They formed New Zealand Carbon Farming in 2010. The business buys and leases land — including from a large number of sheep and beef farmers — and plants it in pine. It then sells the carbon credits, mostly through forward contracts with major emitters. Fonterra, Mercury and major oil companies have been reported among its clients. The company owns or leases 102,000 hectares, including the Fairview and Hazeldean farms in the Waitaki Valley.

Walsh and Miller reject the criticisms that Murray Simpson has levelled at the company — the fires, the pests, the job losses. Walsh says rather than being an environmental catastrophe in the making, the forests will be carefully managed to regenerate into natives. As he describes it, sites have been carefully selected with existing native trees nearby to provide a seed source. After about a decade, he says some pines will be removed and milled for biofuel and natives planted in their stead. Over a century, the remaining pines will be overtaken by flourishing native trees. “You get the carbon you need now to save the planet and you get the indigenous forest that everyone wants,” Walsh says.

Murray Simpson says this is “bullshit”. Native forest is unlikely to regenerate in the dry and exposed country at Hazeldean, he argues. “The only thing that will regenerate in that country is gorse and broom.”

NZ Carbon Farming owners Matt Walsh, left, and Bruce Miller, right, own or lease more than 100,000 hectares of pine trees. Photo: Supplied.

An MPI report found there wasn’t yet much evidence on whether pine-to-native regeneration could be successful, but it said it would be most appropriate in areas with lots of rain, existing native trees, few pests and “should only be attempted at scales which are reasonably manageable”. Last year, Stuff reported that one New Zealand Carbon Farming adviser quit after becoming sceptical of the company’s approach. However another adviser, Auckland University of Technology biogeography professor Len Gillman, is adamant the forests will regenerate.

“It’s absolutely assured,” he says, “because they’re actively removing pine and replanting natives.”

As for the fire, Wash says the property was managed appropriately for fire risk, including fire breaks. “It was maintained exactly the way it should have been,” he says. The pair also dispute that their permanent forests will gut the regions, claiming their land provides at least as many jobs as farming or forestry — the company employs 50 full-time staff and 200 contractors. Again, the available evidence is mixed. A 2020 PwC New Zealand report found carbon forests provided just two jobs per 1000 hectares, compared with 17 from sheep and beef farming and 38 from production forestry. However, Walsh says that analysis didn’t count jobs that arise from actively managing a forest to regenerate into natives.

The looming question is whether New Zealand Carbon Farming — or whoever owns the forests in future — will have the resources to tackle pests and plant natives over a 100-year timeframe. The credits a forest earns eventually taper off as trees age and absorb less carbon. Because of this, a report on the potential impact of carbon farming in Tairāwhiti found that carbon farms wouldn’t even be able to meet their rates bills in future. And landowners in this position can’t simply switch to a new crop — if the trees are felled, all of the carbon credits have to be paid back. When forests become an economic liability rather than a money-maker, who’s going to pay the bills?

It’s a high-trust model. Walsh claims under the emissions trading scheme there are penalties of up to five years’ jail and heavy fines if their forests are not managed correctly. “Bruce and I are literally putting our freedom at risk by embarking on this programme,” he says. However, an MFE spokesperson says there are no penalties for failing to transition a permanent pine forest to natives. In any case, a cynic might observe that by the time we know whether or not the forest has regenerated, Miller and Walsh are unlikely to be alive.

Graph: Courtesy Jarden.

It’s mid-April when I check in again on my carbon investment and I’m reminded of Luka Love’s sense of loss at missing out on the Bitcoin bubble. I’m down 16 cents.

In mid-February, the price of carbon credits around the world began to tumble. The fall was attributed to market jitters from the Russian build-up to war in Ukraine and the fuel crisis — big emitters reportedly needed cash fast and sold up some of their holdings. In New Zealand the drop was more modest, going from the peak of $86.25 to about $70 in less than a month, before slowly beginning to rise again. The first carbon auction of the year, held on 16 March, still breached the new ceiling price, set at $70. Again the government flooded the market with its reserve credits, but unlike last year, not all of the extra credits sold. The auction settled at $70. No one is sure what will happen next.

“We could be down at $50 this time next year,” Diaz- Rainey says, “or up at $150. I wouldn’t bet either way.”

The effect of new government regulations also remains to be seen. Consultation on its plan to ban exotic forests from the ETS has now ended. Beef + Lamb New Zealand has called on the government to go further and limit the extent to which emitters can offset their emissions by planting forests. The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment made similar recommendations in 2019.

The government’s plan to tighten up the rules for overseas forestry investment may also slow the spread of pines. But for a system we’re depending on to address the most urgent problem of our time, there’s a lot of uncertainty.

Luka Love is undeterred. “I’ve got no intention of selling now,” he says. “This is a long-term investment for me and I think the ETS is a good idea, so I’m putting my money where my mouth is.”

George Driver is our South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by New Zealand On Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.