Culture Etc.

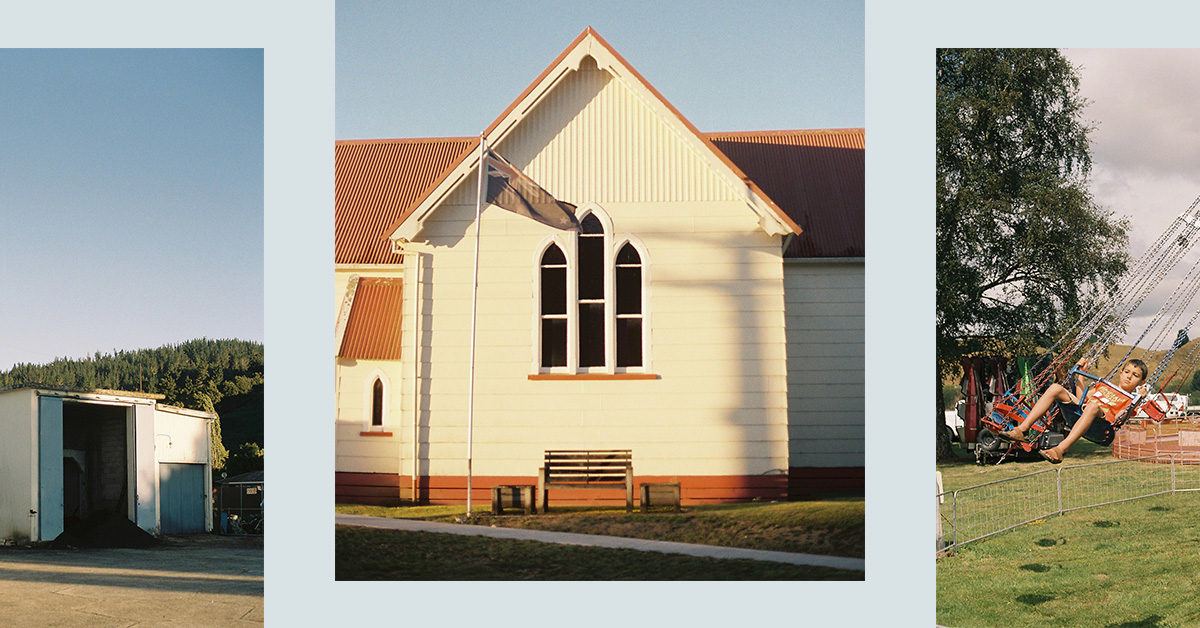

Left to right: The furnace that heats Reefton’s nursing home, a local church, enjoying the swing at the Inangahua A&P show. All photos: Gregor Thompson.

About Town: Reefton

A North Island townie with time to kill spends seven weeks in Reefton, a West Coast town still defined by its beginnings.

By Gregor Thompson

Until relatively recently I had never been stung by a wasp. In fact, I had never been stung by anything — not a bee, not a bluebottle, nor a jellyfish. It was a little detail I shared about myself when stinging or being stung came up in conversation. Not really all that interesting, but something I’d share anyway.

At the end of last summer I found myself with no flat, no income, no real plans and, consequently, a rare opportunity to do some seasonal work. Caught between the pruning and picking phases of the Hawke’s Bay apple season, I ended up taking a job as a field technician for an exploratory geology company down south in Reefton on the West Coast, digging holes and collecting soil to take back to a lab for geologists to examine for gold.

The work consisted of waking up at 6:30am and traversing the dense bush surrounding the small inland town to take soil samples. It was quite straightforward. Every morning, my teammate and I would start by finding the spot we had reached the day before then dig a hole every 20 metres due south until it was time to walk back out again.

From each hole we dug, we collected enough soil to fill up a brown wax paper bag — about a kilo. Each bag ended up joining — and inevitably squashing — the muesli bars and sandwiches in our backpacks. We’d upload the hole’s coordinates to the GPS before moving on to the next spot. The hike out at the end of the day always took longer than the hike in on account of the 25 kilos of dirt loaded into each of our backpacks. If my knees weren’t giving me grief, the terrifying sound of trees swaying in the wind, the “bastard grass” or the incomprehensible geological banter certainly would be.

In the seven weeks I spent toiling, I gained a new claim to fame: I’ve now been stung by wasps hundreds of times. And along the way I accrued some information worth sharing about the town and its history.

Reefton, a natural evolution of ‘Reef Town’, was tactically named in a 19th-century marketing ploy intended to entice prospectors to the area’s significant, gold-laden quartz reef. Early immigrants established a lucrative mining industry that would, in 1888, lead to the first municipal electricity in the southern hemisphere and power New Zealand’s first electric streetlamps. These days, you will find Reefton lamp posts displaying laminated notices suggesting people boil the mains water supply before drinking it.

My field teammates at Reefton Gold were three student geologists and a young and recently apprenticed plumber who, like me, was making things up as he went along. They were all smart enough to have brought cars down with them so they could head home on the weekends. As a townie 300 kilometres and a ferry crossing from home, with no driver’s licence, I spent the weekends instead wandering around, getting to know the place.

In March I attended the annual Inangahua Agricultural and Pastoral Show at the Reefton Racecourse. From the stands I witnessed a 17-year-old girl give her male adversaries a lesson in shearing before applauding a guy named Shane Whittle and his enormous, red-ribbon-winning potato.

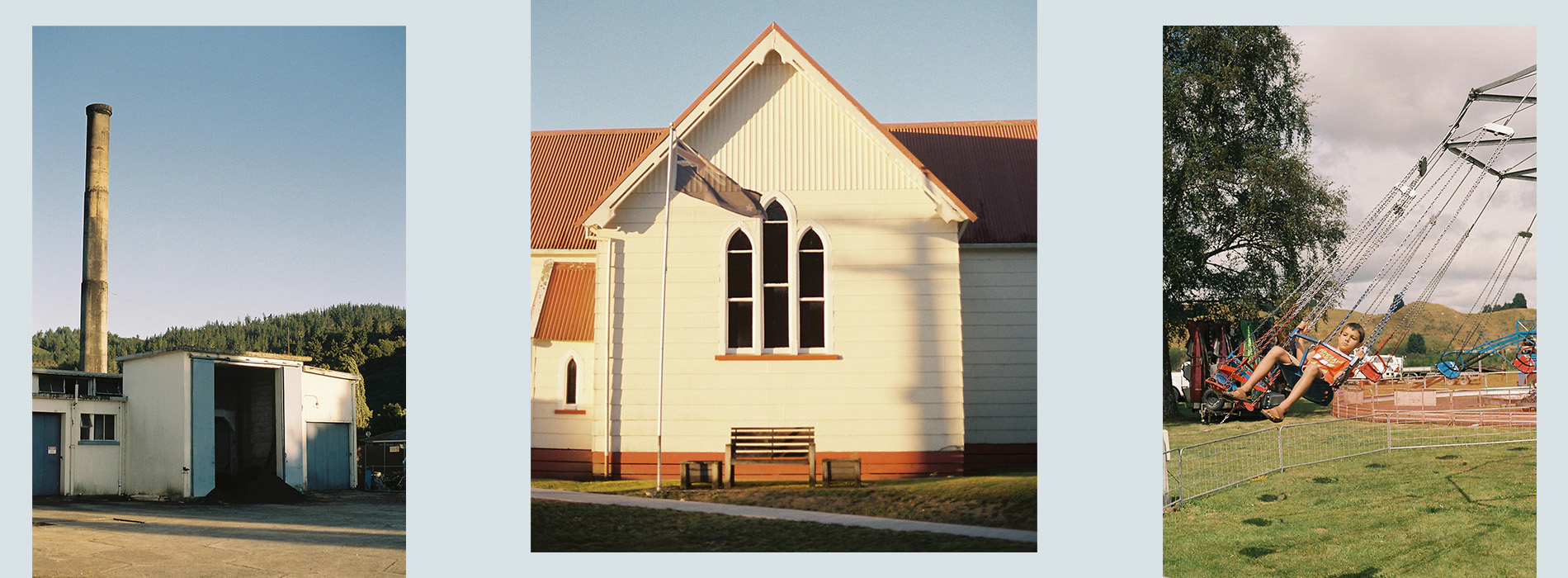

The twins looking at books for their second-hand shop. Photo: Gregor Thompson.

Reefton is not a farming town, however. It’s a mining town in a country whose mining industry has slowly and steadily declined. Gold — the original migrant persuader — became gradually less profitable due to foreign competition and accessibility. The last subterranean gold mine closed its shaft in 1951. As for coal, demand dropped after the majority of ships and trains converted to oil in the mid-1950s; renewable energy has now replaced coal in many other areas.

But there is residual zeal in this part of the country about an industry that others now consider dangerous, arcane and unsustainable. Mining accounts for 22 per cent of GDP on the West Coast and there are currently 12 opencast coal mines in operation in the region, five of which are in immediate proximity to Reefton. Say what you want about the job, but in my experience miners work harder than anyone I have ever come across.

Reefton feels in some ways as if it has become stuck in time. The hostel I stayed at, an old nurse’s home, was heated by a large coal boiler, a piece of technology I had thought long obsolete. So was the retirement home across the street and the local school, where the boiler burns from March through to October. According to residents I spoke to, a carbonised cloud covers Reefton like a king-sized black quilt through the winter months.

If you walk around the streets, hemmed by old miners’ cottages both derelict and revamped, you’ll see signs, posters and bumper stickers demanding justice and accountability for the 2010 Pike River Mine disaster. Everyone you speak to knows one of the 29 who died and everyone has something to say about it. The locals have become justifiably disillusioned with successive governments’ handling of the situation.

Unlike its neighbours Greymouth and Hokitika, Reefton has failed to capture a share of the tourist economy. The pancake rocks and the glaciers draw tourists towards the coast, often bypassing Reefton altogether. All this has taken its toll. Between 2013 and 2018, as the rest of the country’s population grew 11 per cent, Reefton’s fell by 12 per cent.

In spite or perhaps because of this, Reefton may be the best-preserved town in New Zealand. It’s surrounded by beautiful native forest, trout-filled rivers, and creeks that continue to excite gold-panning locals and the odd opportunistic tourist. It’s a town with an enviable stock of Victorian housing whose occupants seem to know everything about one another; a town where the main fish and chip shop doesn’t open on Saturdays. Reefton has a few cafés, three bars, two small competing supermarkets, a modern gin distillery and a few exceptional secondhand stores. There is a sports store that does not stock socks but does display a large collection of firearms. A few doors down, a set of elderly twins wear the exact same thing every single day as they work side by side in their op shop. The monthly quiz at Dawson’s Hotel is enormously competitive, bordering on vicious, where no one is safe from the quick-witted punchlines of Jo, the funniest quizmaster I have ever met.

Just three kilometres southeast of Reefton is Crushington, the birthplace of middle-distance runner Jack Lovelock, who in 1936 won an Olympic Gold medal in front of Adolf Hitler. Today, you would be forgiven for driving through without knowing that — Crushington has virtually disappeared. The statue of Lovelock at the entrance of a bush track is about the only sign the settlement ever existed.

I would hate to see Reefton share the same fate; fortunately, that’s not likely any time soon. For my part, the next time I find myself driving down the Buller Gorge, I’ll turn left at the Inangahua Junction and call in, grab a coffee and have a nosey in the op shops. The coast can wait.

Gregor Thompson is a New Zealand writer now living in Paris.

This story appeared in the May 2022 issue of North & South.