Aotearoa, land of the digital cloud

Overseas tech companies are spending billions of dollars building warehouses to store New Zealand’s — and the world’s — information here. Why?

By George Driver

Datagrid plans to build New Zealand’s largest data centre in a paddock on the outskirts of Makarewa in Southland. Photo: George Driver.

There’s not a lot in Makarewa. Not even a road sign announces its presence. There’s a string of houses interspersed with grazing sheep, a school, a concrete block country club and the kinds of businesses that dot the fringe of regional centres — a petrol station, a timber yard, a tractor dealership. But mostly there are just paddocks lining State Highway 6, which forms a 12-kilometre straight line to the centre of Invercargill.

Trevor Manson has lived in the area for about 35 years. The retired sheet metal business owner says it’s not what it used to be. About 20 years ago the Makarewa freezing works shut down. Then the town hall, the “centre point of the community”, closed. Later, the bowling club and the local hotel went too. The Makarewa Country Club, where he’s a life member, was reduced to a few regulars, “but we’re still hanging in there”.

Lately things have been picking up. A 50 million dollar oat milk factory is being built in the old freezing works site. A new recycling plant is going in there, too. The country club’s membership is growing again.“Makarewa’s going to be quite a hub shortly,” Mason says. “There’s a lot happening.”

And then there’s talk of Makarewa becoming a global tech centre. On a 43-hectare block of farmland three kilometres outside the town a tech company called Datagrid is planning to build a series of warehouses that will contain more computer power than anywhere else in the country. The buildings alone could potentially cover almost 100,000 square metres, an area the size of about 10 rugby fields, although designs are still being finalised. Inside will be up to 200,000 computer servers, potentially drawing as much electricity as a city the size of Hamilton.

It’s not just Makarewa. All over the country, international big-tech players are looking to build enormous data storage warehouses. Lured by New Zealand’s renewable energy and computing-agreeable climate, we’re becoming attractive real estate to store the energy-hungry hardware that powers the world’s cloud computing and data mining. Some local commentators see silver linings for jobs and our own tech industry, others have been asking: What’s in it for us?

“It’s one of those weird things, their very presence stimulates activity . . . I already know that there are people here that are gearing up for it.”

For a township where the current cell phone coverage is ropey, there’s some eyerolling in Makarewa at thought of becoming a global tech hub. The community could host more computing power than Southland — perhaps even the South Island — will probably ever need. But mostly it won’t store New Zealand data. Datagrid plans to build a 22,000-kilometre fibre-optic cable, dubbed Hawaiki Nui, that will run from Makarewa into Foveaux Strait and along the ocean floor to Australia and on to Indonesia, Singapore and Los Angeles. It’s a potential market of tens of millions of people who could soon be storing their information in a paddock in Makarewa.

That’s the vision of Datagrid founder Remi Galasso, anyhow. The French businessman worked in telecommunications in New Caledonia for over a decade and was behind the Hawaiki Cable, a 15,000-kilometre fibre cable connecting New Zealand to the United States and Australia. When it began operating in 2018, it provided just the second internet link between Aotearoa and the United States. Now Galasso believes Southland could become a kind of vault for the world’s data and has the backing of multinational shipping giant, BW Group.

The region has all of the key ingredients, he claims. Its climate means it will cost significantly less to cool the computer servers, normally one of the biggest expenses of running a data centre. It’s also close to the country’s largest hydro power station, Manapouri — the Datagrid site is directly beneath the main pylons running to the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter. If the smelter closes as planned in 2024, Datagrid could consume up to a quarter of Manapouri’s power — about 3.3 per cent of the country’s electricity (although the development isn’t contingent on Tiwai’s closure). The location is also safe — which is important if you’re storing the world’s information. Unlike Auckland, Makarewa’s not on a volcanic field or straddling a major fault line. It’s also hard to think of a location less likely to be bombed in a war.

The final ingredient is Hawaiki Nui, which will provide a fast internet link between Southland and the world. Galasso is also involved in another cable project that will be the first linking South America and the Asia-Pacific, which could be routed through Invercargill, which means the region could become “a digital gateway between South East Asia and South America”.

It’s an enormous project, but this is just one development in what has been called a new gold rush, with international companies looking to tap into New Zealand’s renewable power to store the world’s information.

Where the internet lives

It’s something most of us never consider, but the internet is stored somewhere. Every website we visit, every video we stream, every file we upload to “the cloud” is held on a computer server. At the moment, these servers are mostly offshore in enormous ultra-secure warehouses called data centres. Some of our data is held in centres in Australia — Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Facebook already have large data centres there — but when you surf the web, the information you view could be held just about anywhere. Soon, more of that data will be held here.

On 6 May 2020, when New Zealand was just a week out of its first Level 4 lockdown and the country was glued to the prime minister’s daily 1pm press conferences, Jacinda Ardern delivered some rare good news. Microsoft was set to make a “significant investment” and build three hyperscale (larger than 1000 square metres) data centres in Auckland. While much of the world remained shut inside, Arden said this signalled that “New Zealand is open for business”. In a press release, the tech giant said it aimed to “fuel new growth that will accelerate digital transformation opportunities across New Zealand”.

Two weeks later, Australian company CDC Data Centres announced it would spend $300 million building two hyperscale data centres in Auckland, covering 18,000 square metres and drawing up to 23 megawatts (MW) of electricity (the size of a data centre is measured by the maximum electricity demand of its computer servers) — enough to power about 28,000 households.

Then in September that year, Amazon Web Services (AWS), the world’s largest cloud provider, said it would invest $7.5 billion to build three “availability zones” in Auckland — Amazon-speak for data centres — although, like Microsoft, it has remained mute on how big they will be.

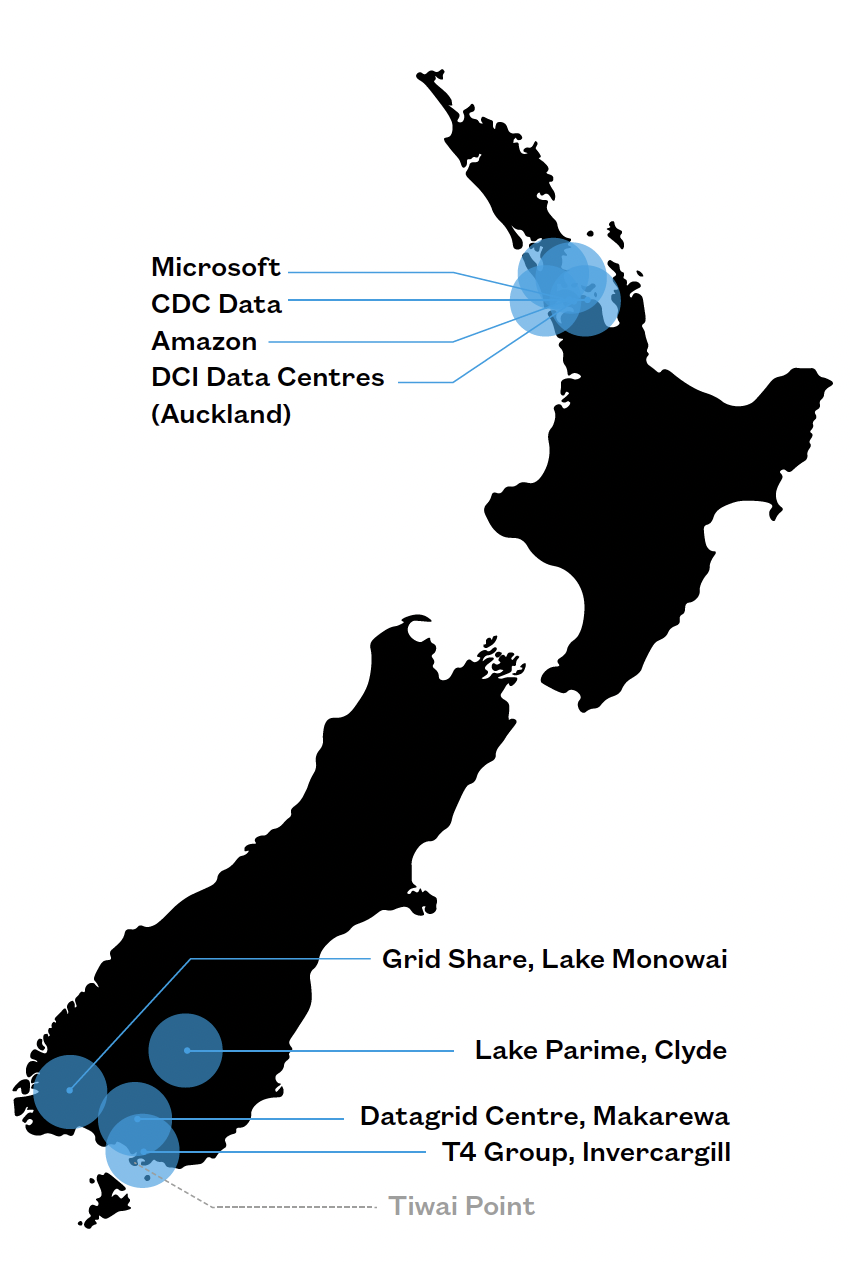

They kept coming. In December 2020, Datagrid announced it would build a 60MW data centre in Southland, and has announced the University of Otago as anchor tenant. Then last year UK company Lake Parime revealed plans for a 10MW data centre in Clyde and Canadian-owned company DCI Data Centres said it would spend $600 million building two data centres totalling 50MW in Auckland. Finally, in March, New Zealand-owned company T4 Group announced it would build a $50 million, 10MW facility near Invercargill.

Remi Galasso, founder of Datagrid. Photo: Supplied.

For Paul Brislen, it’s been something of a dream come true. Brislen is chief executive of the New Zealand Telecommunications Forum, a lobby group representing the country’s major telecoms companies, and has been promoting the country as a potential data centre hub for a decade. New Zealand — and Southland in particular — has the renewable electricity, temperate climate and political stability that data centre operators look for. However, he says his earlier advances were rebuffed. The country was viewed as too small, too far away, too poorly connected.

“Nobody was interested,” Brislen says. “They said there was no need for a hyperscale data centre here because there isn’t a big enough user base to consume it all.”

The major tech companies established in Australia instead. But recently the downsides of building a data centre here have begun to disappear. Until 2017, New Zealand was connected to the world wide web by a single set of submarine cables — the 22-year-old, 30,500-kilometre Southern Cross Cable. Almost all of our internet travelled via six strands of glass fibre, each about the width of a human hair, housed inside this pair of cables. But in 2018, Remi Galasso’s Hawaiki Cable provided a second link to the United States and a third to Australia. A new cable, Southern Cross Next, is expected to start operating this year, giving us another link to North America and across the Tasman. As a result, our connection to the world is now cheaper, faster and more secure.

How the internet is stored is also changing, putting New Zealand at an advantage. Auckland University of Technology senior lecturer Alan Litchfield explains that traditionally cloud storage has been centralised in a few massive data centre hubs, but now tech companies want to store data in multiple locations, so when one site goes down it’s backed up somewhere else. Spreading storage around the globe also reduces latency — the lag that occurs when data travels around the planet.

Paul Brislen, chief executive of the New Zealand Telecommunications Forum. Photo: Supplied.

Litchfield says New Zealand now looks like a good bolt-hole for data, relatively insulated from the geopolitical tensions around China and North Korea and without Australia’s reliance on coal for electricity. Both Microsoft and Amazon claim their New Zealand data centres will operate entirely on renewable energy and all of the companies building centres here have emphasised the country’s renewable power.

“We just happen to be lucky to have a piece of land somewhere that we can fill that hole in the global data map,” Litchfield says.

Exactly what this data centre boom will mean for the country isn’t entirely clear. The tech companies have been eager to emphasise the benefits for the country’s tech sector. Microsoft declined to be interviewed, but in a statement Microsoft NZ’s managing director Vanessa Sorenson said its data centre region “has the potential to super-charge New Zealand’s digital transformation, and build a stronger and more resilient tech sector . . . for the good of our society and our planet”. She noted that the majority of the data centre users were expected to be domestic.

In an interview with North & South, AWS country manager Tiffany Bloomquist also said the company’s investment was driven by New Zealand’s “incredible uptake” of cloud storage and data processing. However, experts say they’re not building them for us. “The data will be housed here but it will be consumed by people offshore,” Brislen says. “They’re not talking about serving the New Zealand public. We just don’t need this many data centres.”

University of Otago big data expert Nigel Stanger says because of our isolation, New Zealand is already well served for data centres for domestic use. “It’s nice for us, but I don’t think they’re doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” Stanger says.

Having data centres onshore will reduce latency, but Brislen says most people won’t notice a difference given data travels at close to the speed of light. It takes about 11 milliseconds for data to reach Australia — about the time it takes sound to travel four metres — while the latency between Auckland and LA is 127.5 milliseconds.

“It’s important if the customer is using a service or app that requires real-time speeds, so voice services, video conferences, playing online games, virtual surgery, digital currency trading, that kind of thing,” Brislen says. “But for the vast bulk the extra few milliseconds in getting something delivered from the US or Australia won’t matter much at all.”

“The data will be housed here but it will be consumed by people offshore. They’re not talking about serving the New Zealand public. We just don’t need this many data centres.”

The tech companies have also emphasised that their data centres will enhance the country’s data sovereignty. Banks and the government are required to store some sensitive data onshore due to security concerns. Māori also consider their data a taonga and Te Mana Raraunga Māori Data Sovereignty Network, a group that advocates for Māori data rights, believes Māori data should be stored in Aotearoa where possible. But under US law, its government can still access data regardless of where it is held as long as it is stored by a US company. Therefore, Litchfield says having data stored here will provide little benefit if it is still owned by an offshore company.

There will be jobs, but most won’t be long-term. Remi Galasso says the Datagrid data centre in Makarewa will require “hundreds of workers” to build and cost more than $1 billion, but it will need only about 45 employees to run. By contrast, Tiwai Point employs about 1000 people with a further 1600 indirect jobs.

Amazon claims its data centres will “support” 1000 jobs over the next 15 years, but says the number of direct AWS employees “could increase” by about 200. Microsoft won’t release details of how many people it will employ or even how much it is spending here, other than it will be “more than $100 million”. CDC and DCI data centres didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

Litchfield says it’s also likely many of the more specialised employees will come from overseas. However, he says data centres are still good for the domestic tech sector as they act as a catalyst for tech development.

“They call it gravity,” Litchfield says. “It’s one of those weird things, but their very presence stimulates activity. I’m absolutely certain that will happen here. I already know that there are people here that are gearing up for it.”

Brislen calls it a “mushrooming effect”. “There’s all the boring stuff — network management, cyber security, data analytics companies — that is generally found around data centres. It operates as a core hub and other businesses spring up around them.”

Southern Institute of Technology school of computing head Oras Baker is hoping for that kind of gravity — or mushrooming — in Southland. The school moved into an impressive new $17 million building in February, built around a 135-year-old Anglican church, but its roll has been decimated by the pandemic. In 2019, the department had 198 students, including 67 master’s students, but about 90 per cent of students were from overseas. The roll has now almost halved to 113 students and just five master’s students.

“Anything new here will be helpful,” Baker says, “because we need to attract more businesses and people to stay here. Even if they only employ 20 or 30 people, every job helps.”

Most graduates get jobs locally, he says, working for the likes of Fonterra, freezing works company Alliance and at the Tiwai Point smelter. But Baker believes future graduates will work for Datagrid and, if it is successful, more tech companies will go south. “Once we show we have the workforce for it, more companies will open centres here and it will make businesses more confident about the future of the region.”

The mining town

On the banks of the Clutha River in the old gold-rush town of Clyde in Central Otago, diggers are preparing the land for a new mining industry. About half a kilometre from the 100-metre-high concrete wall of the Clyde Dam, eight containers are being installed containing 4000 computer servers. Day and night, an as-yet-unknown proportion of these will be mining cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrencies are created and verified by computers solving complex problems, which is enormously energy intensive. It is estimated that Bitcoin mining uses almost as much electricity as gold mining and consumes more than three times the electricity of New Zealand. The country’s major generators say they are regularly approached by crypto-mining outfits seeking cheap power agreements, particularly since China — formerly the world’s biggest crypto mining centre — banned cryptocurrencies last year. Until recently, none had approved the requests. But last year, British company Lake Parime reached an agreement with Contact Energy to build a 10MW data centre on Contact’s land directly in front of the Clyde Dam, drawing enough power to supply about 12,000 households.

The data centre will be able to ramp up and down when power is needed during peak times or in dry periods when hydro generation dips, and will be used for computer processing tasks that aren’t time sensitive — stuff like weather modelling and machine learning, but also crypto mining.

Lake Parime is directly involved in cryptocurrency mining and its subsidiary, Raft Global, sells large-scale crypto-mining hardware. While Contact and Lake Parime are adamant the Clyde data centre won’t be used entirely for mining cryptocurrency, neither will provide details on what its customers will use it for.

Lake Parime corporate relations director Natasha Medlen says the company will run 20 per cent of the Clyde data centre itself and this will be used purely for Bitcoin mining. She says it has “had discussions with several largely USA-based companies” who may rent the remaining servers, but would not reveal what they would use them for or what field they worked in, citing commercial confidentiality.

Contact subsidiary Simply Energy business development director Murray Dyer says it is possible the data centre could be used entirely for cryptocurrency. However, he says Lake Parime is required to have other potential clients to ensure that if the Bitcoin price collapses it can still pay the bills.

“We get at least one inquiry every couple of weeks for pure crypto-mining from China and other countries and we’ve always said no. We have no interest in supporting a pure crypto operation. There’s a straight credit risk from that. But Lake Parime has a diversified business model around high-performance computing services for companies doing AI and rendering or design work that needs a lot of really heavy data crunching but that’s not time critical.”

“Essentially we’d be exporting our power and it’s not like we’re not facing a problem with electrifying our economy with 100 per cent renewable already. This is just going to exacerbate those problems. You kind of wonder what New Zealand’s getting out of it.”

While the data centre will employ only two or three people, Dyer says the greater benefit is that it could make building variable renewable generation, such as wind farms, more economic. Wind farms produce electricity only about a third of the time and if the wind is blowing when power demand is low that power can be wasted. But combining a wind farm with a data centre means there’s always a customer for the electricity. “That is the difference between building a new wind farm and increasing the level of renewables in the system or not building it,” he says.

If the Lake Parime data centre proves successful, Dyer says, similar data centres could be built to support wind farms around the country. He says Contact already has 1000MW of wind farms “in the pipeline” and Lake Parime also says it is looking into collaborating with wind farm projects here.

Other power companies are also planning to site crypto mining hubs next to renewable power stations. In May, a New Zealand company called Grid Share entered a partnership with Pioneer Energy to build a 2MW data centre beside Monowai Power Station in Southland that will be used entirely for Bitcoin mining. The data centre could use up to 30 per cent of the Monowai dam’s maximum power production.

In Clyde, locals have been critical of the Lake Parime project. Lake Dunstan Charitable Trust chair Duncan Faulkner says it will bring zero benefit to New Zealand but will use a large amount of the country’s renewable power. “We’re essentially exporting our renewable energy overseas,” he says. “My concern is we won’t always have excess power available and we need to control it.”

Power hungry

Overseas, countries have banned data centres, at least temporarily, due to their power consumption.

In Ireland, data centres use 14 per cent of the country’s electricity and this is forecast to increase to up to 30 per cent by 2030. There, officials announced a moratorium on new data centres around Dublin due to concerns over energy use and elsewhere they will have to have back-up power to reduce consumption during peak times.

In 2019, Amsterdam banned new data centres in the district and earlier this year the Dutch government announced a nine-month moratorium on new centres while it develops regulations. The latest backlash came after Facebook planned to build what would be the Netherlands’ largest data centre, which attracted widespread opposition due to the amount of renewable energy it would use.

Singapore also instituted a moratorium on data centres in 2019 due to the space and energy they use, although it will allow a limited number of smaller centres this year if they meet efficiency standards.

It’s unclear exactly how much energy data centres in New Zealand will use, but it’s likely to be a significant chunk of the country’s power. Amazon and Microsoft won’t reveal how big their data centres will be or where the renewable electricity they use will come from.

Alan Young, associate director of energy consultancy Enerlytica, has estimated that the servers of all of the proposed data centres could draw up to 450MW. If they were always operating at capacity they would account for about 10 per cent of the country’s power demand. While it’s unlikely they’ll always operate at capacity, this figure doesn’t account for the power required to cool the servers, which can be about a third of a data centre’s energy use.

On the other hand, Young says large data centres are very efficient, so can reduce overall energy usage if businesses move their storage from inefficient on-site servers and onto the cloud. The International Energy Agency estimates data centres use about 1 per cent of the world’s electricity and that proportion has been flat for the past decade, despite internet traffic increasing 17-fold, because of improving energy efficiency. But if New Zealand is storing more of the world’s data then it’s unlikely to result in domestic energy savings.

In any case, the country’s generators claim they can build more power stations to serve them — in fact they are actively courting new data centres. Meridian, Contact and Mercury all cite data centres as a way to increase energy demand in their latest annual reports. But the country is already facing a power challenge. Transpower expects electricity demand to increase by 68 per cent by 2050 as we attempt to electrify transport and industry to reduce carbon emissions, and other models show power demand could more than double. On top of this, the government wants to stop generating power from coal and gas by 2030.

Data centres actual and proposed, nationwide.

University of Otago research fellow Jen Purdie has been projecting our future energy demand and supply and says in future there needs to be greater scrutiny on new major electricity users, like data centres.

“We can certainly build a lot more wind and solar farms to supply data centres, but there is a limit,” Purdie says. “The question is whether building these large data centres now — which are owned by offshore companies and create few jobs — will negate a New Zealand-based energy-intensive industry establishing that could create lots of more jobs in the future.”

Purdie says data centres could significantly reduce their impact on the electricity grid if they were able to reduce demand during peak times, as is required in Ireland.

Even if we can power them all, University of Auckland electricity market analyst Stephen Poletti says the added demand could also push up electricity prices.

“Essentially we’d be exporting our power and it’s not like we’re not facing a problem with electrifying our economy with 100 per cent renewable already,” Poletti says. “This is just going to exacerbate those problems. You kind of wonder what New Zealand’s getting out of it.

Both the national grid operator, Transpower, and the market regulator, the Electricity Authority, say they haven’t investigated how the new data centres will impact the electricity network, but they believe the added demand could mean more generation will be built.

In Clyde, Duncan Faulkner says it’s time to look at regulating the industry. “At the moment, the only rules they have to abide by are the local district plan on what the building can look like and noise levels,” he says. “And that’s not the issue here. The issue is renewable energy being used to process overseas data.”

In Makarewa, the locals aren’t quite sure what to expect. Trevor Manson says they are planning a community meeting in the country club so people can raise questions with Datagrid, but at the moment many feel left in the dark. David Hart lives in a modern brick and tile house on a lifestyle block beside the Datagrid site and says he first learned of his new neighbour on Facebook a couple of months ago.

“I thought, ‘What’s a data centre? It’s just a big box with wires coming out of it, isn’t it?’”

His main concern is whether there will be noise and traffic from the development, and if the company’s financial clout could mean it faces little regulation. The company is yet to apply for a resource consent, but Southland District mayor Gary Tong has previously said he’ll do his “damndest to make sure the right processes are in place to make sure it goes through smoothly”.

Across the road, Robbie Birch was worried he’d soon be looking out his window at an enormous warehouse. However, he’s since met with the company and has been told the data centre will be a single storey and set back from the road. Now he just hopes the development will mean he will be able to get a decent internet connection — most houses here have to use a slow rural internet service and cell phone reception is patchy at best.

“It’s pretty hopeless,” Birch says. “You have to lean against a window at a certain spot to use it.”

But no one is quite sure if Makarewa is set to become a tech hub, or if the cloud gold rush will turn out to be a mirage.

George Driver is North & South’s South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by support from NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the July 2022 issue of North & South.