Culture Etc.

Above: Fonofono o le nuanua: Patches of the rainbow (After Gauguin), 2020.

Paradise Camp

In a groundbreaking exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale, art, history and gender lines are redrawn, bringing Pacific fabulousness to the sinking city.

By Tobias Buck

The South Pacific has arrived at the 2022 Biennale di Venezia in a wave of lush, glorious technicolour. It’s late April and Yuki Kihara’s exhibition Paradise Camp has just opened in the Aotearoa New Zealand Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, the world’s oldest and most prestigious visual arts event. On centuries-old stone walls hang ocean-blue island imagery and tapa cloth from floor to ceiling. But there’s more going on here than bright colours and sparkling surfaces.

The salt-water highway that brought Europe to the Pacific has now brought the Pacific back to Europe, this time on the southern region’s own terms. Kihara is the first Pasifika, first Asian, and first transgender artist to represent New Zealand in Venice, a groundbreaking achievement (and one which was supposed to happen last year, before Covid-19 lockdowns put the 2021 Biennale on hold for a year). “It feels surreal,” she says on opening night. “I’m exhausted, excited. All of the above.” When Creative New Zealand let Kihara know she’d been chosen to represent Aotearoa, she was in Sāmoa. She had to show her mum on a map where Venice is.

Dressed in a bright gold suit jacket and green print scarf at the biennale’s opening, Kihara has a sense of poise and energy about her. She’s petite, diminutive even. But she stands and sits very upright, talking in precise, measured tones — a natural presenter. Then suddenly she’ll interrupt herself, veering into a spontaneous side-comment, or burst into gently self-mocking laughter, clapping her hands before recomposing herself. Kihara helped organise some of New Zealand’s first fa‘afafine beauty pageants in the early 2000s, and she has an energy about her which is pure pageantry — an outgoing warmth that’s immediately inclusive and appealing. At the biennale she has initiated a “Firsts Solidarity Network”, an initiative for artists who are at the biennale as first-time representatives from a marginalised or under-represented community in their respective countries.

“If you’re a visitor you are immediately taken to a whole other world — a fa‘afafine Utopia,” Kihara says.

Kihara is known for bold, interdisciplinary work which grapples with the complexities of post-colonial histories in the Pacific, particularly as they intersect with her perspective as fa‘afafine.

Paradise Camp, a remarkable immersive installation combining photography and video works, was first conceived after she attended a presentation on Māori encounters with Western explorers given by the academic and lesbian activist Ngahuia Te Awekotuku at the Paul Gauguin Symposium in Auckland way back in 1992.

With her 2008 show Living Photographs, Kihara achieved another first — the first person of Samoan descent to have a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was there she built on Te Awekotuku’s talk and developed the idea for what would become Paradise Camp, while visiting the works of French impressionist Paul Gauguin on the Met’s second floor. Gauguin is famous — and infamous — for his colourful portraits of French Polynesian women, works which are both an important part of post-impressionist art history and the frequent subject of debate for critics who argue they are exploitative, colonial and chauvinistic. Kihara found herself inspecting his pieces closely; the vibrant clash of colours and the familiar gender-neutrality of the models intrigued her. “I sat there and just kept looking at the painting, and I began to ponder the history of Indigenous queer culture in the Moana Pacific, and how Gauguin may have provided a visual record of that through the Tahitian and the Marquesas community.”

She was inspired too by the traditional Samoan faleaitu (house of spirits), performances made for chiefs to present topical issues. For her, the connections to modern drag performance were obvious.

The 12 main images of Paradise Camp on display in Venice upcycle the French painter’s instantly recognisable works. Alongside the video work First Impressions: Paul Gauguin, they are ensemble pieces created by a team of 100 helpers across Sāmoa, shot on location in rural villages, churches, plantations and heritage sites. A turquoise backdrop which might initially read as a tropical paradise is, on closer inspection, the landscape of a beach destroyed by a tsunami. The tableau images both challenge and tease: seductive surfaces, saturated in light, belie their subtle depths. Kihara’s own poise reflects a considered political and aesthetic position. In one work she appears as Gauguin, lifting her chin at the viewer, recreating his gaze and challenging his perspective. It’s performative and enlightening in the way great drag can be, a redrawing of power and gender lines that’s both arch and artful, significant and fun-filled.

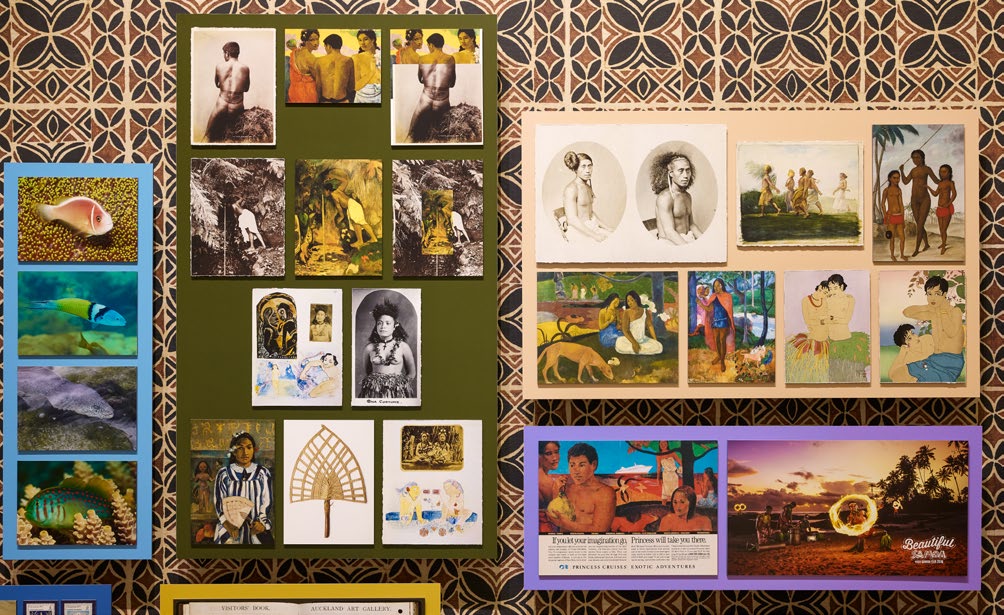

Kihara’s works are accompanied by a “Vārchive”, detailing the relationship between Gauguin, early queer Polynesian history and this installation. Kihara describes the Varchive as “personal research, rare books by 19th-century explorers, colonial portraits, pamphlets, news items, a geological sculpture, activist material and visual links between Gauguin and Samoa. It provides a back story or a living story of how Paradise Camp came into being.” The archive is not just storage for dead information but rather “a living entity that helps to provide new meaning in the present”.

All the works forefront the fa‘afafine community, offering conversation about climate change, people, gender, community and place. “If you’re a visitor you are immediately taken to a whole other world — a fa‘afafine Utopia,” Kihara says. “A worldview according to me.”

Born in Upolu to a Samoan mother and Japanese father, Kihara is a dual citizen of Sāmoa and Aotearoa. She spent time growing up in Osaka and Jakarta too, before she moved as a 16-year-old to boarding school in Wellington. After leaving high school she studied fashion; now in her 40s, she has been based in Samoa for the last decade. Kihara says the first artists she learned from were fashion designers: Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, John Galliano, Jean Paul Gaultier and Vivienne Westwood. She was drawn to the avant-garde and theatrical. That study led to work in film, television, costume design and fashion editorials, all practices where Kihara’s ideas about bodies, image-making and representation could continue to evolve.

As fa‘afafine, she is also part of a community of one of the four genders customarily acknowledged in Samoa. Besides the binary roles of ‘man’ and ‘woman’, Samoans also recognise fa‘afafine, people born as men who express themselves through femininity (the name translates directly to “in the manner of women”), and its inverse, fa‘afatama: people born as women who express masculinity.

Her work is performative and enlightening in the way great drag can be, a redrawing of power

and gender lines that’s both arch and artful, significant and fun-filled.

Yuki Kihara in her exhibition Paradise Camp, curated by Natalie King, New Zealand Pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Luke Walker.

“I knew I wanted the fa‘afafine community in Sāmoa as my primary audience,” Kihara says of Paradise Camp. But that community is not always understood by outsiders. For instance, climate change and disaster responses are primarily based on a Western man/woman binary that excludes fa‘afafine, she says. During the aftermath of the 2009 tsunami in Sāmoa, many fa‘afafine were first responders in the rescue efforts. Kihara says the emergency shelters set up by NGOs failed to address their needs — they did not offer gender-appropriate bathrooms, for example. “As a result, a group of fa‘afafine set up camp at an abandoned house, living without necessities while continuing with rescue efforts.”

In making Paradise Camp, Kihara deliberately conceptualised the work as being similar in scale to a major film production. “Five years ago, I began doing a recce around Upolu Island with my local producer Dionne Fonoti and cultural adviser Letiu Lee Palupe, figuring out the logistics and production budget,” she says. Despite having “absolutely no funds to make it happen”, she pulled it off. Kihara employed local people in Samoa, including those in the fa‘afafine community, helping them gain new skills. And it does take a village to prepare a show like this. The core team behind Paradise Camp, supported by the Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa, comprises assistant Pasifika curator Ioana Gordon- Smith and curator Natalie King, a professor of visual arts at Melbourne University who helped with the exhibition of Australia’s first Aboriginal artist Tracey Moffatt at their pavilion in 2017. “As a Samoan and Moana woman,” says Gordon- Smith, “it gives me immense pride to see Paradise Camp and see Yuki representing on the global stage.”

When King first contacted Kihara three years ago about presenting in Venice, the artist “flat out declined her”. “I had tried to develop a proposal to represent the New Zealand pavilion twice, and it failed. I said to myself, ‘Maybe the Venice Biennale is not for someone like me’.” Calling her eventual success a privilege, Kihara says it means a lot to the artistic community she is part of. “The Moana art community [has] been struggling to gain recognition not only within our respective island nations but internationally as well. Contemporary art in Moana is thriving, and it’s not going anywhere.”

Paul Gauguin with a hat (After Gauguin), 2020.

Two Fa‘afafine (After Gauguin), 2020.

Since New Zealand has no permanent pavilion at the biennale, Kihara and King visited Venice in November 2019 to find a location. The day they arrived the city was flooded. It was the Acqua Alta, Venice’s notoriously high waters that appear each year when the tide from the Adriatic rises. The water lapped below Kihara’s knees. Luckily, she’d remembered her gumboots. “I think there are issues faced by Venice that parallel those in the Pacific Islands,” Kihara says. “Both islands are at the front line of the environmental crisis.” Both too share a dependency on tourism and a deep history of trade. “What I would like to bring to these common issues is a perspective about how we address these in the Moana, and particularly in Sāmoa, from a fa‘afafine perspective that’s simultaneously indigenous and queer.”

Like many other places in the Pacific, Sāmoa has experienced climate-related disasters such as extreme cyclones, floods, coastal erosion and coral depletion. Seventy per cent of the country’s population lives in low-lying coastal areas. While the global average for sea-level rise is 2.8 to 3.5 millimetres a year, Sāmoa experiences rises of about 4 millimetres a year, adding to the effects of storms and high tides. This is just the beginning — Sāmoa is one of several Pacific islands which could entirely disappear if we don’t tackle climate change.

After navigating their way around an exceptionally watery version of Venice, Kihara and King decided to show Kihara’s work in the Artiglierie, one of the biennale’s prime spots. Luckily it hadn’t yet been booked. By the main entrance of the Arsenale, it’s the first pavilion in the row of a long wing with high foot-traffic, with high ceilings and a “super fabulous” gallery space.

At the April opening Haniko Te Kurapa, the kaihautū for New Zealand at Venice, shares a proverb from the late Piri Sciascia: “He mana tangata, he toi whakairo: Where there is artistic excellence, there is human dignity.”

“There were people who were sceptical about whether my team and I were able to secure it,” says Kihara of their venue, which was pricey to secure. But just like her project with no budget, Kihara has made it happen.

Like a gracious pageant host welcoming the audience to the start of the show, she tells me: “I’m happy to say the New Zealand pavilion is in the Arsenale with a fabulous presentation of Paradise Camp. ’Nuff, said, shut the gate!”

The 59th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia is on until 27 November 2022. People can view Paradise Camp virtually at nzatvenice.com

In 2023, Paradise Camp will tour to the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

Yuki Kihara’s Vārchive, Installed in the Artiglierie at the Biennale. Photo: Luke Walker. All artwork courtesy of the Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries.

Tobias Buck is a North & South contributing writer.

This story appeared in the June 2022 issue of North & South.