The Misery-Go-Round

New Zealand’s child protection agency, Oranga Tamariki, is constantly in the headlines for all the wrong reasons. But is it the institution that is flawed or the society that expects it to fix bigger problems? Aaron Smale unravels the causes of decades-long failure and what is needed to finally address systemic issues.

Portrait photography by Aaron Smale

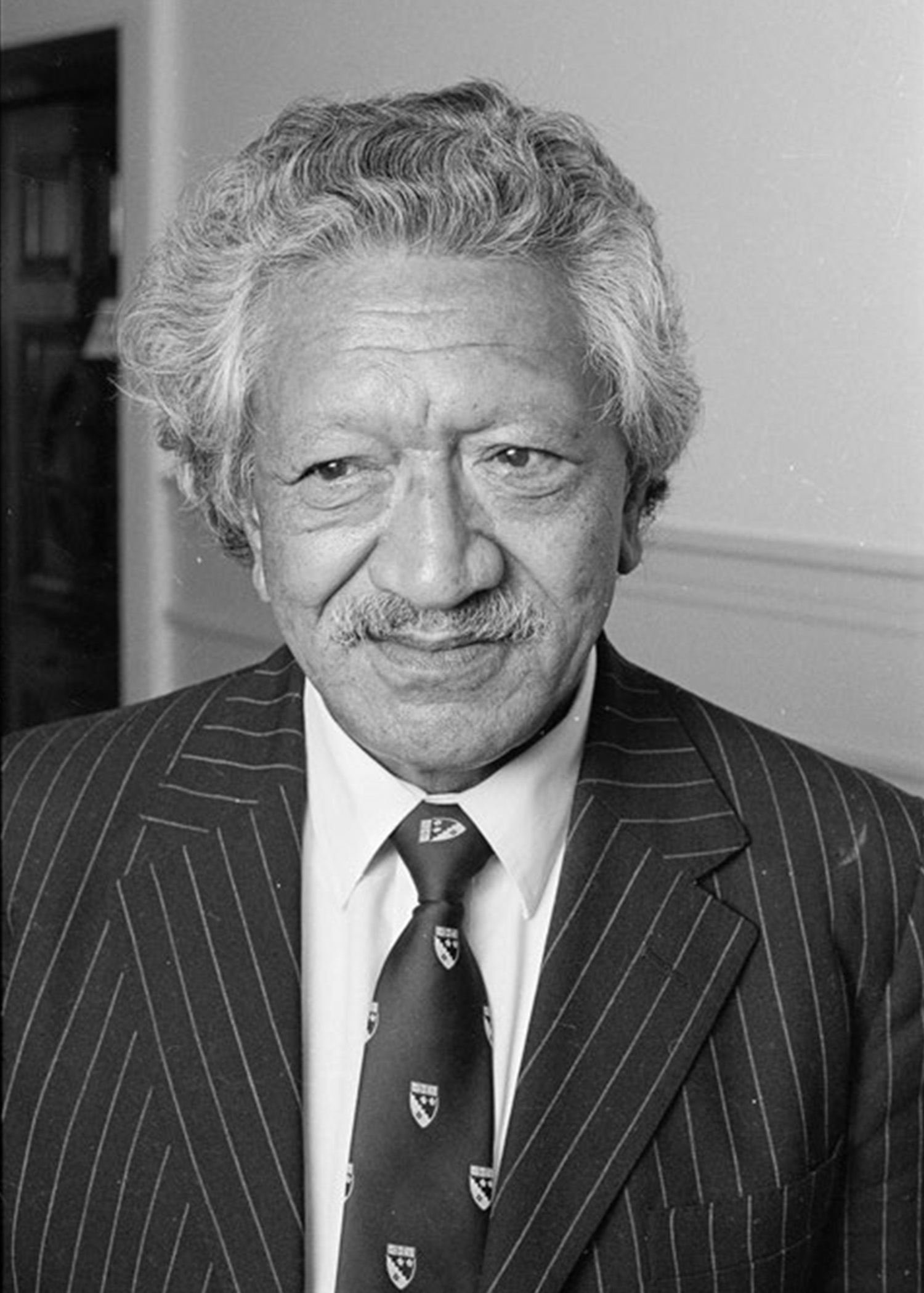

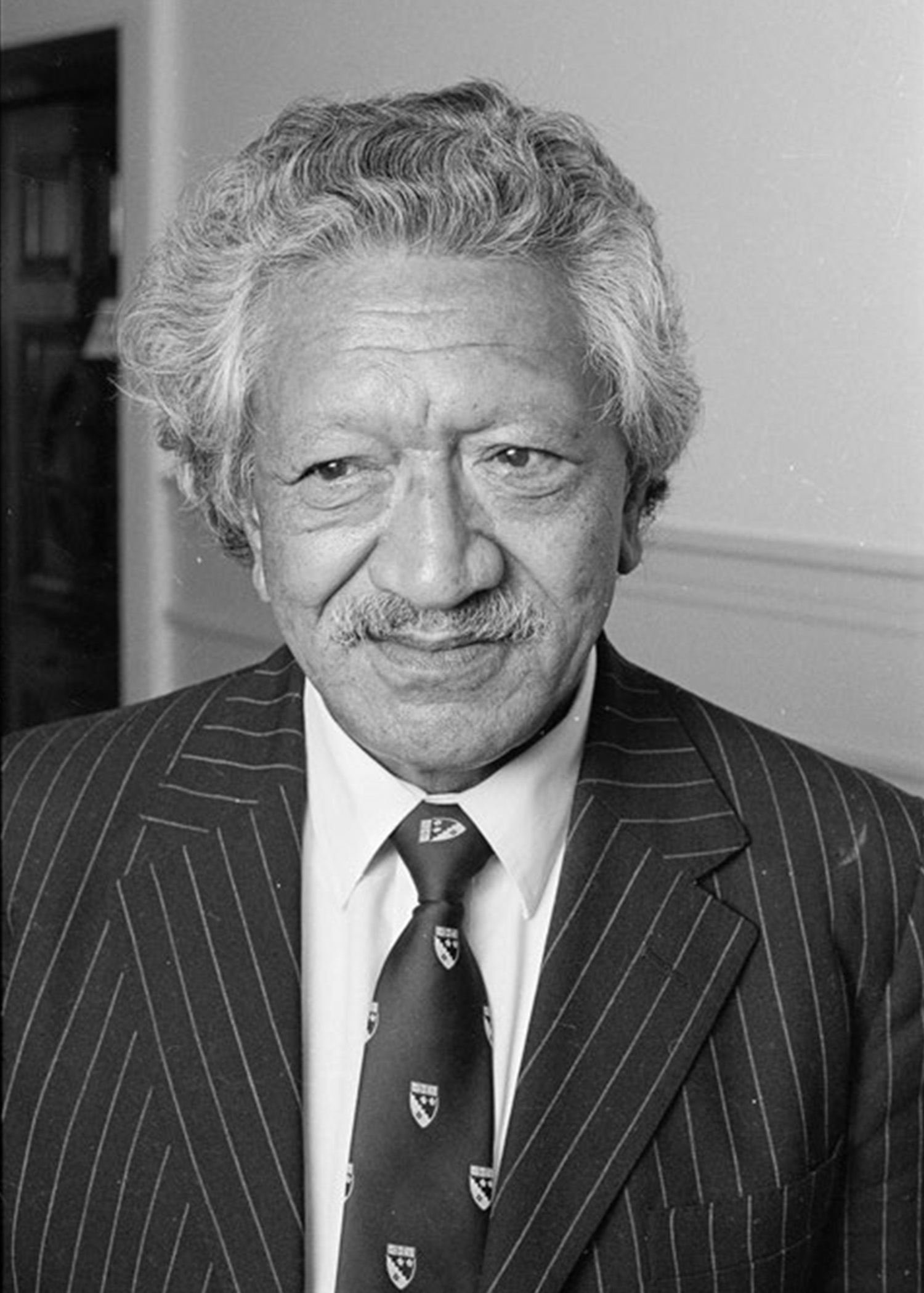

Māori leader and social worker John Rangihau chaired the inquiry that resulted in the report Te Puao Te Atatu. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

It’s no longer even a scandal. The failings of the state’s child care and protection agency, Oranga Tamariki, are now just regular news fodder. Stories about harm to children in state custody and institutional blunders barely make the top of the news cycle or linger for long on the home page of news sites. Harm to children and their families by the state is just filler. Like car fatalities, it has become almost an inevitable, if unpleasant, reality that can only be mitigated, never completely fixed.

Just within the two months prior to this story going to print, Stuff reported a male Oranga Tamariki caregiver on trial for allegedly having a threesome with a 13-year-old boy. The New Zealand Herald published a story that Oranga Tamariki had wrongly accused a mother of abusing her children for 20 years, in a case of mistaken identity. RNZ reported that a $40 million programme to help children who had been sexually abused had significantly underspent its budget and was closed down.

While such headlines now seem to elicit a national yawn rather than howls of outrage, the ongoing litany of horror stories end up on the desk of the Minister for Children, Kelvin Davis.

“Your blood pressure goes up,” he says of the grim news cycle. “[But] I welcome the scrutiny. I think it’s really important that these things are aired. This was exactly the reason I asked to become the Minister for Children. Because as a teacher, as a principal, as a father, abuse in all its forms, it’s just abhorrent to me. And we’ve got to do something about it. Because what we’ve been doing for the last six or seven decades hasn’t worked.”

Davis is right about the history of failure. Unfortunately, the government he’s part of risks only adding to that legacy.

Mechanisms to hold the state accountable when it inflicts harm remain woefully weak. Baseline standards of accountability are still lacking. Although the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care has recommended legislation to make the state liable if children in its care are abused, the Oranga Tamariki Oversight Bill produced by the government late last year gives little reason to expect that level of accountability will be introduced. The government hasn’t even formally responded to the commission’s recommendations.

And critics of the bill fear the consequences of its intention to split the oversight and care of children across several agencies, potentially muddying issues of legal liability. They question the part increasingly played by large non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that rely on a pipeline of government money – and an ongoing demand for the services they provide.

“The Crown can’t even follow its own laws.”

Oranga Tamariki’s failures weren’t always given the regular coverage they have had recently. The agency’s current news profile is an abrupt shift that can largely be attributed to a documentary by Newsroom investigations editor Melanie Reid, which aired in June 2019.

Typically, reporting on child welfare had focused on individual cases of children, often Māori, dying at the hands of family members. The stories would be met with public outrage and government agencies flagellated for not doing enough to prevent such deaths. Such coverage was often followed by a surge in children being removed by the child protection agencies.

Reid’s documentary opened up another conversation — maybe the state’s interventions weren’t so necessary. Maybe the state’s interventions were actually causing harm. New Zealand’s shocking statistics of children being abused and too often killed by those who should care for them is paralleled by an abhorrent history of children suffering abuse while in the custody of the state. Reid’s footage added another chapter to that story.

Ngāti Kahungunu leader Ngahiwi Tomoana had heard about the story before he saw it aired. The details of the children’s protection agency, Oranga Tamariki, using its powers to try to take a newborn from a young mother had filtered back to him from the people directly involved, kaumātua Des Ratima, and midwives Jean Te Huia and Ripeka Ormsby. All had intervened to try and stop the removal of the hours-old baby, or “uplift” in Oranga Tamariki’s jargon.

If he was uneasy about what he’d heard, he was shocked by what he saw. When he watched Reid’s documentary, Tomoana not only recognised those trying to defend the mother and baby. He also knew those trying to take the baby.

“When I saw the video, my best mates were the ones doing the yelling. I was in Social Welfare with them in 1988. They were brought in for their people skills. It just shows me how systems can convert you. Because two people that were from the community, Māori, were suddenly turning around and, ‘Give that baby now or I’ll have the police arrest you!’ That probably shocked me more than anything.

“How could this end up so bizarre? Lucky I did leave in 88 because I could have ended up like that too. That’s what it does for our people in that system. My mates, who I thought would be staunch forever, buckled under the system and I saw them as victims as well. They still haven’t talked to me.”

What he saw made him appreciate, those who put themselves between the parents, baby and the social workers. “They were ready to risk everything. But what they did do was expose the chronic and toxic nature of that whole environment. That’s something we’ll always be grateful to them for.”

Reid’s documentary, New Zealand’s Own Taken Generation, was shot mostly on mobile phones. The raw and emotional footage of the attempted removal was heartbreaking and infuriating: the confused young parents, the baffled and angry midwives, the “I’m just doing my job” social workers despatched in the middle of the night to remove the baby boy based on a risk assessment to which the whānau was not privy; the police officers who were called to help Oranga Tamariki enforce the court order.

The footage hit like a bomb, generated a ham-fisted response from the government and would in turn launch five investigations and as many reports. Internal emails from Oranga Tamariki show a panicked response and the rapid application of legal pressure to pull the footage offline. The argument put forward by the Crown was that the documentary breached Family Court rules that didn’t allow participating parties to be identified (the mother and child’s faces were obscured).

However, that attempt to yank the documentary and the response from politicians didn’t address the central part of the story: that the state was acting in bad faith and in a bullying fashion to try and take a baby from its mother less than 24 hours after birth. The documentary showed that Oranga Tamariki completely disregarded the family’s attempts to come up with a plan that prevented the need to remove the child.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and then-Minister for Children Tracey Martin initially put on a similarly blustering front, claiming they were not going to watch it. This was disingenuous at best, or simply a way to avoid talking about what looked like an unnecessary abuse of power.

But the documentary and the actions of the state it captured spoke for itself. It was a George Floyd moment — people whose only power was the phone in their pocket recorded the immense abuse of power by the state and revealed it to anyone willing to look.

And plenty of people were willing to look, including those in various watchdog institutions. Heads have since rolled, most notably then-chief executive of Oranga Tamariki, Grainne Moss, who stood down in January 2021. The documentary generated a swarm of reports from all directions. The failings those reports found were at every level and stretched back decades.

Before those reports landed, eminent legal scholar and Māori activist Moana Jackson made an observation that would prove to be an apt summary of the whole disaster: “Never mind tikanga. The Crown can’t even follow its own laws,” he said, cutting straight to the heart of the matter, as he so often did.

Indeed, the reports not only showed the Crown breaking its own laws, but also breaching its own policies and practice standards. The documentary’s exposure of the state’s attempt to take one baby from a young mother in Hastings cast a harsh spotlight on the whole “child protection” system. What was revealed was that the incident in Hastings was not an anomaly but a single example that illustrated widespread and systemic failures.

Following the Newsroom revelations, the Ombudsman reviewed 74 similar cases over two years, and the resulting report zeroed in on some of the central legal issues. The Chief Ombudsman, Peter Boshier, was eminently qualified, having previously been the head of the Family Court. He paid particular attention to the use of section 78 of the Oranga Tamariki Act, the section that gives the ministry powers to remove a child. The section is theoretically a last resort and the ministry is obliged to take a number of preliminary measures before exercising this power.

The Ombudsman’s report found this was not what was happening in practice. Boshier found that the training manual used for guidance on using section 78 was brief and inaccurate. He also discovered that “without notice” removals — where parents weren’t given any prior warning or chance to respond (as had happened in Hastings) — were the norm, not the exception. The section-78 without-notice applications were also executed when the mothers were heavily pregnant or had just given birth, as was the case in the documentary.

“The use of without-notice section-78 applications for interim custody should be reserved for urgent cases where all other options to ensure the safety of pēpi have been considered,” the report stated. “The lack of appropriate guidance on this issue is a serious failing in the context of the Ministry’s routine reliance on such applications.”

The Ombudsman revealed that Oranga Tamariki had inflicted trauma and harm on people who had already experienced trauma at the hands of the state. “It also appeared to me that trauma-informed practice was not entrenched within the Ministry. I was unable to find any evidence that the Ministry’s staff saw the parents’ childhood histories, as well as experiences of being in care themselves and the Ministry’s prior removal of their children, as traumatic events for parents that required a different response.”

Oranga Tamariki’s attempted removal of a newborn baby was exposed in a documentary by Newsroom’s Melanie Reid. Photo courtesy Newsroom.

Boshier also found that Oranga Tamariki had used its coercive powers in a way that violated basic legal and moral principles.

“Overall, the failure to undertake the Ministry’s own key checks and balances that have been built into the system severely compromised the quality, robustness, and transparency of the Ministry’s decision making. This is particularly concerning because of the wide-reaching and coercive nature of the Ministry’s powers, and the overwhelming impact the use of these powers can have on individuals and their whānau.”

The powerful statements did not end there. “Crucially,” Boshier wrote, “the Ministry must be guided by the legislative presumption that tamariki are entitled to know and be cared for by their parents. Additionally, the parents’ rights to know the allegations against them, and to have an opportunity to respond, are at the heart of Aotearoa’s legal system, and are of central importance in the context of the coercive powers of the Ministry.”

Another report hit desks in Wellington, this time from the Children’s Commissioner, former judge Andrew Becroft. He picked up on the intergenerational nature of the trauma caused by the same agency that was intervening once again, citing damning statistics. Becroft noted that “48 percent of the pregnant women in 2019 for whom the state decided during pregnancy to remove their pēpi Māori after birth, had been in state custody themselves, compared with 33 percent of non-Māori.”

The Children’s Commission also found that at the end of June 2019, 6429 children were in state custody, 4420 of them (69 per cent) Māori.

Oranga Tamariki’s own review of the Hawke’s Bay incident, which looked at the ministry’s broader practice, found numerous shortcomings, reinforcing the findings of other reports. It found the organisation had not followed its own legislation. “The statutory authority delegated to Oranga Tamariki social workers was not consistently well-understood or appropriately applied . . . The combined adverse impact of these events on the mother, father and whānau was significant.”

The review also found Oranga Tamariki’s overreach impacted on the actions of other agencies, particularly the hospital staff, creating confusion and undermining their role. “Hospital staff were unclear about what would happen when, and their role in supporting their patients through the removal. This put them in the position of having to compromise their own relationship of care with the mother and baby.”

Also investigating was the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agency, the funding arm of the NGO set up by former government minister Dame Tariana Turia to offer services to Māori through government contracts. In other cases it investigated, the agency found multiple examples of coercive, heavy-handed tactics involving not just Oranga Tamariki but also armed police.

A number of individuals and groups, including the National Urban Māori Authority, filed a claim for an urgent inquiry with the Waitangi Tribunal. The Tribunal held an inquiry, and also heard from those who had existing claims with the Tribunal (Declaration: I have a claim on adoption that was included in the hearing).

In April 2021, the Waitangi Tribunal found that Oranga Tamariki’s actions were a breach of the Treaty of Waitangi in that they were a coercive intrusion into the home of Māori.

“The signatories to the Treaty did not envisage any role for the Crown as a parent for tamariki Māori, let alone a situation where tamariki Māori would be forcefully taken into state care — in numbers vastly disproportionate to the numbers of non-Māori children being taken into care,” the tribunal said, noting that the disparities caused by generations of Crown breaches were used “as a basis for ongoing Crown control”.

These various reports unpicked the failings of Oranga Tamariki in meticulous detail, in some cases tracking these failures back over several decades. They made numerous recommendations that focused on fixing the operational failures and rethinking what Oranga Tamariki’s function should be and how it should be carried out.

But in their focus on the child-protection system, the reports often overlooked many of the political shifts and societal changes that shaped the response of Oranga Tamariki and its predecessors over decades. By overlooking this context, the mountain of official condemnation landed only on the one government institution.

How did an agency with such coercive powers go so far off the rails? Why are Māori so overrepresented in the statistics? Who should have the authority to remove a child and on what basis? What should intervention look like?

To put the question another way: How did the people who tried to remove the baby in Hastings end up behaving in such a way that one of their close friends didn’t recognise them?

Midwife Jean Te Huia first saw Oranga Tamariki taking newborn babies in 2015.

“Take the kids . . . Put them somewhere for the night. Then it became a week. Then a year.”

Jean Te Huia’s gaze softens with nostalgia when she starts talking about Tomoana Freezing Works. Prior to her three decades as a midwife, Te Huia (Ngāti Kahungunu) worked with thousands of others for one of the biggest employers in Hawke’s Bay.

“I remember the happiest times at the freezing works were the celebrations, like Christmas. You’d walk down the freezing works chain leading up to Christmas and you’d hear a whole volley of 300 men singing “Silent Night”. And it would be beautiful. When they finished there be a couple of seconds of silence and then they’d break out into yahooing and banging their knives.

“Everyone was connected like whānau — knew when people’s birthdays were. When there was a funeral and any family member died, they’d do a collection, there’d be a koha, there’d be $3,000 or $4,000 given to whānau members. If someone got sick, there was always someone to do baking or help them. So the freezing works wasn’t just a place of employment, it was a place of whānau connectedness. People felt good about what they did and who they worked alongside and that was all taken in an instant.”

When Tomoana closed in 1994, it was the second Hawke’s Bay freezing works to shutter in less than a decade. The first blow had come in 1986 with the sudden closure of Whakatu, just outside Hastings.

Like many kids of his whanau and generation, Ngahiwi Tomoana had worked at Whakatu since he left school at 15. “We could make 150 bucks a week, which was a princely sum in those days, without having any qualifications at all, just the ability to get up every morning and slog it out and do it again the next day, and the next month and the next year.

“It was hustling, it was bustling, it was rough and tough, rough and tumble, there were fights every day, but no one got hurt. There were arguments every day, but everyone turned up the next day. We had the sharpest weapons in the world but no one got stabbed. And so we were able to tolerate each other and still let the production roll on and allow the economies of our whānau to burgeon.”

Tomoana was clearing thistles on a newly bought property when he heard the news over the radio that Whakatu was closing. “It was a bit like 9/11 — you think you’re watching someone else. That can’t happen to us. We’re too big, we’re too strong, we’re too powerful, we’re too much of a whānau. So sure enough, boom! It hit us, hit us hard. The next day a lot of our workmates all turned up here. And they said, what are we going to do?”

The same community spirit that permeated the workplace swung into action to support the over 2000 workers who were suddenly out of the only job they’d known. Backyards and marae land was ploughed up and put into gardens. A community support centre was set up. But the economic and social disaster would unfold over months and years as the shock wore off and the reality set in.

“We made sure everybody was active and committed even though we knew there was going to be a big thump sooner or later.”

Tomoana estimates that 70 to 80 per cent of those who were laid off managed to recover and get back on their feet in some way, whether that meant retraining and finding other work or heading for Australia. But he says around 20 per cent of those who lost their jobs fell into a hole and some have never pulled themselves out. A study carried out at the time by public health expert Dr Papaarangi Reid and others found an increase in suicide and self-harm. Despite this increase in mental distress there was no increase in admissions to hospital for mental health care.

Ngahiwi Tomoana, outside the old Whakatu freezing works near Hastings.

“The most injured party were those who depended on the work solely, had built their life around the works, were living from season to season, and expected their children and their grandchildren to work there,” says Tomoana. “They were the ones where the curtains closed and the doors shut and were hard to get to. We went around banging on doors, banging on windows, yelling through keyholes, trying to get people to come out and respond and be part of the whole recovery.

“Those whānau took a whole lot of time and healing to recover. And some of them still haven’t. Third generation unemployed, third generation under the thumb, and needing desperate help to break that cycle three generations later.” He says the response of successive governments over decades has created a vicious cycle. “It’s the misery-go-round. And people are profiting off it, building fortunes off it.”

The economic upheavals and sudden unemployment of the 1980s and 90s were a major turning point for many Māori communities. It was only two generations on from the urbanisation of the 1950s and 60s. And when whānau suffered, children suffered.

At the start of the last century, many commentators were still of the belief that Māori were a dying race and government policy often reflected that neglect. As their land was lost, poverty followed. Writing in the early 20th century, Māori doctor Maui Pomare said the most urgent health issue facing Māori was infant mortality — he conservatively estimated that more than half of all Māori children died before the age of four.

Children have always been central to the Crown’s response to how to manage and control Māori. The British Crown’s first representative, James Cook, abducted two Māori boys off the coast of present-day Gisborne to gain information about Māori society. He then abandoned them further along the coast. Cook carried out a ritual in Mercury Bay, claiming New Zealand for the British Crown based on the European doctrine of discovery — which gave European monarchs the right to claim sovereignty over foreign lands. That set in motion the colonisation of Māori and all that followed.

Missionaries targeted children for their “civilising” goals, but often ran into trouble when dishing out corporal punishment. This provoked an indignant and sometimes violent response from the children’s elders. There are numerous early accounts from explorers, artists, traders and missionaries themselves that Māori did not physically punish children, and that children were treated indulgently, particularly by men.

Mission schools established by the churches were superceded by Native Schools, which came into being in 1867 after the first phase of the Land Wars. Their establishment coincided with other key changes, including land confiscation. The worst legacy of these schools was the physical punishment of children for speaking their mother tongue, inflicting trauma and stripping the Māori language from generations of Māori children. Like the Indigenous residential schools in North America and the mission schools in Australia, they were also responsible for creating a position for Māori at the bottom of the economic ladder. It was government policy to prepare Māori children for low-skilled employment, right up until the late 60s — historian John Barrington wrote that politicians and government officials generally had a view that “the appropriate place of Māori in the social scale was at the lower end, whether as rural labourers or later as tradesmen or manual workers”. Educational policy reflected this.

The structure of Māori society and families themselves were targeted in waves of legislation relating to Māori land. The individualisation of native title broke down the communal nature of Māori society. The state tried to extend this into families. A native land act in 1908 ruled out the practice of whāngai, or adoption within the wider whānau, to try to simplify succession to land interests. This legislation was ignored in practice as Māori continued to raise children within wider kin networks. But the wording of this 1908 statute was then inserted almost verbatim into the 1955 Adoption Act, effectively taking the whāngai adoption option off the table for Māori children who ended up in the state adoption system.

This section of the adoption legislation was part of a massive surge in government legislation trying to address what was spoken of as “the Māori problem”. The problem was twofold. After World War II, following years of official neglect, the Crown realised Māori were not only alive and kicking, they were moving into cities and towns because their land holdings had all but disappeared.

Post-war, the Māori population exploded, growing even more rapidly than the general baby boom that was occurring throughout New Zealand and other Western countries. The number of Māori, according to census data, jumped from 82,000 in 1936 to 167,000 in 1961 — more than doubling in just one generation.

The government’s own economists raised red flags about the implications of this, but the response was always behind the reality. In 1940, economist Horace Belshaw wrote that: “There is an unambiguous picture of a people whose land resources are inadequate, so that a great and increasing majority must find other means of livelihood . . . if it is accepted that the Māori must be economically self-supporting, large numbers must migrate to other districts, many of them to towns. . . . Until the full implications of this are understood there is no solution to the Māori problem. They are not yet understood either by the Māori or European communities or by the Government.”

Belshaw’s words still stand. The Māori shift to urban centres in the post-war period raised fundamental questions about the place of Māori in New Zealand society that have never been fully addressed and are still the source of political friction today.

The Māori urbanisation of the 1950s and 60s is often portrayed as a period of cultural alienation and dislocation, which led to various social problems in subsequent generations. This is only partially true. For many Māori whānau, as for New Zealand in general, this period was one of general prosperity. The availability of work meant the standard of living for many Māori was raised considerably. But this was based on an abundance of employment in labouring jobs, particularly in the rural sector — Māori became concentrated in large employers like freezing works.

Perhaps the larger challenge facing Māori during this period was Pākehā prejudice, both at an individual and institutional level.

Sometimes that racism ran right down the middle of families, as in Jean Te Huia’s experience. “My dad’s parents were Pākehā and were very racist. My grandfather did not like my Māori mother. She was often left sitting in the car in the driveway, wasn’t allowed in the house. We grew up not really understanding that racism.”

Archives New Zealand has numerous files where the names alone are jarring “Race Relations — Integration/ Segregation”, “Incidence of Colour Line” — let alone the contents. Māori Affairs kept a tab on incidents of racism and found plenty of examples of not just individual prejudice but segregation in picture theatres, pubs, banks, housing and public toilets.

Housing was a perennial source of conflict as private developers and landlords often refused to sell or rent to Māori. One file notes a memo by a Pākehā officer at Māori Affairs who was interested in buying a house. The real estate agent was quite happy to sell him one, until he turned up with his Māori wife. Newspapers of the day carried stories of Pākehā neighbours objecting to Māori moving in next to them. Māori Affairs was caught in a dilemma with trying to provide for a surge of Māori coming to the cities while other government departments, like housing and the State Advances Corporation (which provided loans and mortgages), were often reluctant to assist. Initially there was a resistance to making state housing available to Māori.

The initial solution was what was referred to as “pepper-potting”, scattering Māori throughout Pakeha neighbourhoods in order for them to learn to assimilate. The idea was a response to the fear of Māori concentrating in areas that then became ghettoes, replicating the urban slums of the United States which had already faced the city-bound migration of African Americans since the early 20th century.

But the pepper-potting experiment eventually collapsed under the weight of prejudice and sheer numbers. Areas like Freemans Bay in Auckland had slid into slum housing: cramped Victorian “workingmen’s” cottages with poor sanitation. In the late 1950s, the council and central government condemned and demolished streets of these homes. Many of those who lived there were relocated to newly developed suburbs such as Ōtara in South Auckland, creating virtual racial segregation overnight. While Māori and Pacific Islanders were seen as a potential threat to social order, they were also a source of cheap labour for the industrial zones that sprouted in the south of the city. This pattern was replicated in towns and cities throughout the country.

Freezing workers at Whakatu, Hastings, circa 1920s–30s by Henry Norford Whitehead. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

But it was also these communities that were hit with state surveillance and policing when the growth economy slowed in the late 60s and 70s. Children were increasingly funnelled into welfare institutions. Tens of thousands would be so incarcerated from the 1960s to the late 80s. Many of these children then went on to form the basis of the country’s prison population and gang membership. By the time this generation arrived in adulthood and parenthood, Māori communities were bearing the brunt of the redundancies and unemployment that followed Rogernomics.

After years of disquiet, a group of Māori social workers raised their concerns about institutional racism within the then-Department of Social Welfare. This led to an inquiry chaired by Tūhoe leader and Māori Battalion veteran John Rangihau. The result, after dozens of hui around the country, was the seminal 1988 report, Te Puao Te Atatu: A New Dawn.

Donna Hall (Te Arawa) was a newly minted lawyer when she was asked by Rangihau to join the inquiry committee. She said the other members of the committee were pragmatic about what child protection could look like but based it around a broad definition of whānau. “They understood the whole migration of Māori into the cities meant that there were going to be new forms of community, and that didn’t frighten them,” she recalls. “Puao Te Atatu was about finding ways to make the Māori communities that the children came out of stronger so that they could keep the accountabilities for these children back within those communities.”

The report and the legislation that came out of it — the Child Youth and Families Act 1989 — were and still are considered ahead of their time, but the new dawn proved to be a false dawn. Social Welfare was renamed as Child, Youth and Family Services (CYF) and the report and the legislation made whānau, hapū and iwi central to addressing the issue of children at risk. But while the new legislation said whānau should be at the centre of child care and protection, Māori communities were being economically battered. As the Lange government threw off the state controls on the market, it began to impose more coercive control on those who were the casualties of that unfettered market and the drastic changes it unleashed.

In a perverse inversion, some of those who had been laid off jobs in the freezing works were then offered new employment in welfare and prisons. “At that time there was a huge recruitment for redundant workers to go and work in CYF and all those places. I was one of them,” says Ngahiwi Tomoana. “I looked through all the social-work files and I thought, I know all these folks, most of them had whānau at the works or at the railways or the post office. They’re easy to redeploy.”

But he was put off by the attitude of those at the top. “At one point there the minister of social welfare, I think it was Michael Cullen at the time, said, we don’t care who’s chucking them in at the top, we’re in the business of fishing them out at the bottom. So never mind your ideas. We’re in the business of fishing people out of the gutter not running upstream to see who is throwing them in.”

It was then that a marked step-up began in removing “at risk” Māori children from their families. “The only answer seemed to be extract, extract, extract,” says Tomoana. “Take the kids out. Put them somewhere for the night. Then it became a week. Then a year. Whānau wasn’t even thought of, even though Te Puao Te Atatu was all about whānau.”

The social policy of the day, which has extended up to the present, was to punish the victims of damaging economic policy. This extended into the criminal justice system.

“In 1988, the government was looking at building a prison in Hawke’s Bay. It was more than a coincidence that it was around the same time as the freezing works was closing and everything else was closed,” says Tomoana.

“We got together here with our heavyweight kaumātua and they said to the Minister of Justice, how much to build this prison? $25 million. How much to run it every year? $5 to $7 million. Give us half the building cost and half the running cost and we’ll keep our people out.

“But it was like a runaway train. It was a train wreck with us watching it happen. They built 660 beds in the prison, didn’t listen to any of our kaumātua, filled the bloody thing up and they’re looking at building more prisons. All our solutions to our own issues have been subordinated or undermined or dismissed by successive governments.

“The first tranche of colonisation is land loss. Then language loss. Then loss of your loved ones. That’s the ultimate victory of colonisation when you’re stripped of your whakapapa. They’ve got all the land; they’d smashed our language. Now take the babies.”

Elison Mae was failed by Social Welfare but later went to work as a solicitor for its successor institution.

“You look like nothing’s happened.”

It was first that wouldn’t even register for most teenagers. But for Elison Mae opening her own mail was something she’d never experienced growing up. Her foster parents at the time — who she called Aunty and Uncle — told her she had a letter. She was 16 at the time. Decades later, her expression at the memory of it is still that of an excited teenager.

“I noticed it wasn’t open and I might have even said, it’s not open. Uncle said, ‘Well it’s not addressed to us it’s addressed to you.’ And Aunty said, ‘I think it might be your School C results, and I said, ‘Oh.’

“I said, ‘I might just take it into the toilet.’ Because I didn’t know how to react. I was so used to not exposing my emotions.”

Mae didn’t know how to react because she’d never been allowed to believe she was smart or important or that she even mattered just a little bit. The young woman was still captive to the little girl.

The young woman is now a retired lawyer living in Whanganui. Mae sits in the sun-drenched living room of her flat, reflecting with amazement on the trajectory of her life and how the little girl managed find a way out of the darkness that was her childhood.

“She had things being done to her by adults that should never happen to any person, let alone a child,” Mae says of her childhood self. “For that child on one level just to survive either a hiding from her mother or a grown man fulfilling a depravity of his own on this little human body, that in itself was pretty amazing. But you give away nothing. You don’t look like you’re sad or hurt because you have been. You look like nothing’s happened.”

There is a distance in the way she talks about her mother, rarely referring to her as Mum, more often by her name, Eleanor. Despite this, she has come to understand her mother.

“Mum had some serious mental health issues. She was the result of incest. My mother had a pathological temper and anything could set it off. Anything. She was quite a tragic person, I think. I got to know a little bit about her upbringing. That’s how I found out about the incest. I had heard stories that Social Welfare had found her in a dog kennel. I had heard a story that her bed was the bath. I think she would have suffered horrific abuse herself.”

Mae’s father, who was Pākehā, had his own, different, flaws. “He was like a gentle giant, he was a big kid. He mumbled, he liked his alcohol. He never worked. He never hit us. He was a gentle man but he really was childlike.” She now puts his behaviour and limitations down to a head injury he’d reportedly suffered as a child.

Her childhood was a chaos punctuated by regular violent outbursts from her mother, transience because her father couldn’t or wouldn’t hold down a job, and a parade of strangers boarding in their house and inflicting sexual abuse on the children.

“My 14-month-old sister was sexually assaulted amounting to GBH [grievous bodily harm]. There was a police file made available to the Department of Social Welfare. Nothing was done. It didn’t matter, well it did matter, but it didn’t matter whether that assault was on me or my brother or my 14-month-old sister, the point is, nothing was done. It had probably already happened to me and my brother at some point but nothing again was done. Because here we had the Department of Social Welfare and nothing was done.”

When the welfare authorities did step in, they often screwed that up as well, Mae recalls. She remembers foster parents who gave her stability and safety, but occasionally she was also exposed to harm in foster placements. A number of her siblings ended up in some of the worst welfare and psychiatric institutions, including a brother who went through Hokio Boys Home and Kohitere Boys Training Centre, and also did a stint in Lake Alice psychiatric hospital as a nine-year-old. A sister went through Miramar and Kingslea girls’ homes. The lives they lived subsequently attest to the harm they suffered.

The contents of the envelope that the 16-year-old Mae opened in trepidation — discovering she had indeed passed School Certificate — would be one of the first steps in finding a way to escape what had happened to the little girl and discover her own potential and place in the world. She went to university and graduated with a double degree in psychology and education. After having her own children, she went back to university in her mid-30s and completed a law degree. The adult Elison then revisited the little girl Elison by getting a position as a solicitor at Child Youth and Family, the successor to the very institution that had failed her as a child.

She found many good people trying to do the best job they could under extremely difficult circumstances. But she also found deep flaws and systemic failures that could sometimes lead to serious consequences for children, while the institution itself would suffer none at all.

“I just wanted to make sense of everything I’d been through. I figured having been a child in care, that it would give me some sort of unique insight that other people wouldn’t necessarily have. And it did, it really helped me working with social workers.”

As a frontline solicitor she would advise social workers on the legality of their proposed decisions, but often the advice would be ignored or not sought.

“Nine times out of 10 there was often a resistance to legal until the shit had hit the fan, and then it was too friggin’ late and we were trying to pick up the pieces. If you’d come and seen us to begin with, we might have been able to avoid this.”

Her experience was borne out by the Ombudsman’s inquiry after the incident in Hawke’s Bay. In 77 per cent of the cases he reviewed, there was no evidence of consultation with the ministry’s solicitors.

Mae says there are a number of steps outlined in the legislation between an initial notification and the most drastic step of removal that are often not properly implemented by social workers or the ministry. The ministry is legally obliged to investigate a notification of concern, and matters can either be resolved or escalated at different stages of the process. The final and most drastic step is to remove a child under section 78. But the many reviews after the Hawke’s Bay incident showed this step was being used as the default option.

Mae says that while the ministry can impose conditions on parents, it too has obligations. She sometimes found a laxness over meeting those conditions.

Mae often comes across parents like her own who are seriously neglecting and abusing their children. But the legal forum these issues play out in often aren’t conducive to putting children first. “We talk about the welfare and best interests of the child as first and foremost. But that’s very difficult in a court room when it is an arena of conflicting rights — the rights of the mother, the rights of the father, and the rights of the child — and the child is the least able to give effect to their own rights. But I also think our children need to stop being political footballs as well.”

If the well-being of children is the measure, then at what point should the state or some other entity intervene? What should the purpose of that intervention be and how is the well-being of the child measured? To what extent is the well-being of a child simply a reflection of the well-being of their whānau? And how do these hot-button topics play out in the media and political discourse?

Emily Keddell of Otago University. Photo courtesy of the Otago Magazine.

The high “lifetime costs”

University of Otago Associate Professor Emily Keddell has spent over a decade delving into the policies and practices that seek to answer those kinds of questions. “I think there’s a mismatch between how the state defines what the problem is, even now, and what family’s actual needs are,” Keddell says.

Keddell was a social worker in Britain before switching lanes and researching the policies underpinning child protection in New Zealand. Her research found that the neoliberal ideology that took hold in the 1980s became hugely influential in child-protection policy. Any failure was pinned exclusively on the individual. But the impacts of what were benignly called “market reforms” often fell heavily on Maori and especially heavily on children. Policy around children then became narrowly focused on those who were “at risk” without addressing the reasons underlying that risk.

“I think there’s this constant battle to try and reshape those views of what policy for children actually should be. Policy for children has to include some attention to the economic policies and settings.

“There was a big push through the 90s of getting people off benefits by cutting benefits and all of that stuff. Within a neoliberal political context, those issues are viewed as very separate from an issue of child abuse.”

Keddell says how policy is sold by politicians of various stripes can be totally at odds with the ideology that drives it. Many of the policy proposals that have rolled through child protection are defining the problem in narrow ways that totally disregard other factors, she says. She points to the use of the terms like “vulnerable” and “at risk” that cropped up in the 2010s and were used to invoke sympathy for children whose circumstances supposedly pointed to them having a high chance of being abused by family, and that frame the state as saviour.

However, the terminology masked what the policies were actually about. Cabinet papers from 2016 that informed a review of CYF stated that: “Despite our best efforts and significant investment, children and young people who have required the intervention of the care and protection and youth justice systems have dramatically worse outcomes as young adults than the rest of the population”. The paper went on to note that those who come to the attention of CYF have high “lifetime costs”, mostly related to “subsequent benefit receipt and involvement in the adult criminal justice system, rather than investment in preventative services”.

This narrow analysis excluded factors like the economic position of those who come to the attention of CYF — poverty — and the fact that many of the parents under the ministry’s scrutiny had themselves gone through the welfare system and may have been abused in that system.

But by defining the problem as children in state custody creating high “lifetime costs” —involvement in the criminal justice system, being on a benefit — the government saw the solution in “prevention”. That prevention boiled down to “remove the child as early as possible”.

That definition of “prevention” has driven interventions that are increasingly coercive and aggressive and, as was seen in the Hawke’s Bay incident, bordering on unlawful. Keddell says a key turning point was a report in 2015. “The expert panel review report came out in 2015 which was led by [later Dame] Paula Rebstock. The report led to the creation of Oranga Tamariki. But the language around removing children at the earliest opportunity to safe and loving homes, that was the first time that language had been used. I think that had a direct effect on practice. One or two years later came social investment, which sort of solidified that ‘get in early and get them out to the safe and loving homes’, rather than doing anything for families we’re taking them off.”

Perhaps it was no coincidence that midwife Jean Te Huia first witnessed children being removed at birth by authorities was in 2015. She was present at a birth when social workers “walked into the delivery suite and took it off me and the mother. I did not believe I was living in a country where that could happen.”

Keddell says the statistics around the removal of children can be deceptive. The Care of Children Act allows Oranga Tamariki to place children in permanent foster homes. This takes them out of the statistical picture because they are technically no longer under Oranga Tamariki’s care, she says. But many of those babies were removed from families under circumstances similar to the Hawke’s Bay case, where questionable, if not unlawful, legal methods were used. The children were often never given back.

Another factor that exacerbates the situation is Oranga Tamariki, like many government agencies, has taken to using data modelling to predict risk and trigger intervention. The whole concept of “social investment” was an attempt to apply this modelling to social policy.

“It was really trying to use data, integrated data, that was becoming more available in 2015 to predict who would become a high cost to the state in the future, and then focus prevention most on those groups.” Political ideology, Keddell suggests, plays into how data is applied. “In a right-wing government, the view of how to do that was quite limited.”

Overseas studies have shown that the modelling is often grossly inaccurate — the modelling is only as good as the data it is based on and the interpretive methods applied to that data.

“The underlying data kind of reflects a lot of institutionalised racism, you’re not really improving decision making.” She says in the US this bias is against African Americans while in New Zealand it is against Māori. “They’re not actually that accurate, because the underlying data is biased and drawn from administrative sources.”

Keddell says the use of some of these management tools is often driven by institutional self-preservation rather than assessing risks to the child.

“The whole managerial risk-aversion stuff really came into play in the late 90s, early 2000s. A lot of procedural compliance kicked in, which means that the agency becomes more concerned about protecting itself really. Organisational risk gets conflated with risk to the child. It’s like, ‘We better do something in case something goes wrong, and we get bollocked for it.’ Which is a perverse outcome of being constantly lampooned in the media.”

Keddell says there is some evidence that these changes brought an increase in child removals that wasn’t justified by the actual data around harm to children. So what level of harm justifies intervention and what does that intervention look like?

Sarah Whitcombe-Dobbs worked as a psychologist in CYF, then moved into research, completing a PhD on the assessment of parenting capacity in child protection. She says the decision to intervene and remove a child by Oranga Tamariki is only one small part of a larger conversation we need to have about the well-being of children in Aotearoa.

“The vast majority of children who are abused and neglected in New Zealand remain in the care of their parents. And so how do we support those parents to parent in a way that that, first of all doesn’t harm their kids, but allows their kids to develop according to their potential? Yes, there’s a question around uplift into care. That’s the severe, severe end. But the reality is that we have a horrific child-abuse situation in New Zealand, and most of those remain in the care of their families.

“We have windows of development and early childhood that we never get back in terms of . . . cognitive and language and relational well-being.”

Whitcombe-Dobbs says she has noticed how the language used to describe children perceived as vulnerable can suddenly shift at a young age, particularly if they are Māori boys. At a young age they are no longer perceived as vulnerable or victims and are instead portrayed as a risk and a threat.

“I think we tolerate violence towards boys, little boys, and young men as a society. I worked in the severe-behaviour service at the Ministry of Education, and [with] these boys who have behaviour problems. And they were victims, right? Pretty much every case I worked was a care and protection case, they had experienced abuse and neglect. And so they would be framed as victims by teachers and kind of understood as such, with a lot of work on my part, up until about the age of eight. And then the language just changed to perpetrator or physical assault.

“These are kids who have been victims of violence, who, while they’re still children become framed as perpetrators, when those who have committed crimes against them have never been held to account. And the injustice of that, particularly for Māori boys, is just rampant.”

In her research she talked to parents who were potentially exposing their shortcomings to a relative stranger. Whitcombe-Dobbs says they were like any other parents who love their kids. “The parents who I have involvement with have the same hopes and dreams that I have for my kids. The failure to meet the kids needs consistently is in my view, for the most part, a ‘can’t’, not a ‘won’t’. And I really do believe that all parents can change. It’s whether the parent can change in a timeframe that’s sufficiently urgent.”

For Elison Mae, her parents didn’t change and she doesn’t think they were capable of the kind of change she needed as a child. The state that failed to intervene when it should have and often butchered it when it did is still falling short. But she says Oranga Tamariki’s role cannot be viewed in isolation from other issues.

“When you’re working in care and protection you see the overlap with mental health, you see the overlap with poverty, you see the overlap with drug addiction, you see the overlap with domestic violence. All of these things. You see the overlap with having nowhere to live. Housing. All of these things come into impacting on that child or young person.

“I don’t think it matters whether it’s the state, whether it’s iwi-based, whether it’s hapū-based, do you deal just with care and protection without dealing with all the other stuff? Actually you can’t because they’re all intertwined.”

“If we agree that this isn’t a political issue, that it’s a humanitarian issue, then we might make better progress.”

Tupua Urlich: “They’re not learning from mistakes.”

“It’s just a system that recycles — recycles trauma, recycles pain, poverty.”

Tupua Urlich (Ngāti Kahungunu) is an active voice in Voyce, an advocacy group for children in state care. But he also knows personally of the grief the state has caused over generations.

“My father had three brothers. His youngest brother killed himself in Mangaroa prison in 2018. My father, he was killed. His other brother died of an accidental overdose. The last one, he died of a heart problem, but he lived with severe schizophrenia.

“My father and his brothers went through the Department of Social Welfare homes. When I was living with my uncle, he talked about the shit that he went through in there and how that made him who he is, and the abuse and shit that they went through, and he climbed the ranks in the Mob.”

Urlich’s involvement with Voyce led to him speaking on the steps of Parliament in 2017, during a protest about state abuse, and more recently responding to changes being made in Oranga Tamariki. But he has found that the repeated rounds of consultation are mostly a box-ticking exercise.

“They’re not learning from the mistakes, they’re not addressing the needs,“ he says of the consultation loop with Oranga Tamariki. “They’re profiting off the damage done by the gaps in society, the lack of support, intergenerational trauma and the effects that has on people who go through that system, who then go on to become parents and are trying to manage that on top of their own trauma. And it’s just a system that recycles – recycles trauma, recycles pain, poverty, and keeps benefiting and profiting off it.

“We need accountability. There needs to be some liability on the government for what they’re doing to our kids. How dare they assume that they should go without facing any consequences for removing children from whānau where they’re unsafe and placing them with strangers who are equally unsafe, if not more dangerous.”

There is a din of competing definitions of what the problems are with Oranga Tamariki and a multitude of proposals about how they should be addressed.

After the forest of paper that resulted from the Newsroom documentary, Kelvin Davis decided he needed another report and has set up a ministerial advisory board now chaired by Sir Mark Solomon.

A lot of the changes Davis is trying to implement are about addressing operational matters on the front line, while also pushing towards more of those operational matters being devolved to entities outside Oranga Tamariki.

“Currently around 80 per cent of decision making and power and everything sits with OT and 20 per cent sits with communities,” Davis says. “Over the next five or so years, I want to reverse that balance, so 80 per cent with communities, and OT’s role is as the enablers of community aspirations.” As it stands today, Oranga Tamariki has an operating budget of $1.3 billion.

Davis says he is also having conversations with his Cabinet colleagues about what their departments are doing to address some of the issues that lead to children being at risk.

“If the country had implemented Te Puao Te Atatu in the mid-80s, we’d be having a very different conversation,” he says. “All the reports since have reinforced the direction, the thrust of Te Puao Te Atatu. Really, that’s what I’m trying to implement. So communities, hapū, iwi, community providers all pool their talents, their knowledge, their experience for the best interests of any particular child and all their family that come before them.”

Davis is well aware that the issues in some families go back generations and often have origins in the trauma that previous generations experienced in state custody. He recalls meeting a gang member who told him about how he was removed from his home, despite there not being any abuse. He spent four years in boys’ homes and joined the gang as soon as he got out.

“It’s easy to blame those people for their behaviour. They’ve got all this trauma that needs to be unravelled, but our solution is to throw them in prison. We really do have to sort this out. We just can’t keep blaming people, we can’t just keep building more prisons.

“We’ve got to actually take stock of the impact that decisions in the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s have had on the well-being of people.”

While Davis has inherited a system that has inflicted intergenerational harm, his mandate is only to fix what the current system is doing on the ground. Many of the flaws identified by the swarm of reports are slowly being addressed — section 78 uplifts have dropped in numbers — but the scandals keep coming.

Davis doesn’t have the remit to address some of the structural issues or the institutional inertia — and outright resistance to change — that permeates a bureaucracy that has a history of failing to confront its own mistakes. As an example, he can’t discuss the legislation before Parliament, the Oversight of Oranga Tamariki System and Children and Young People’s Commission Bill, as it falls under the remit of his colleague, minister for social development Carmel Sepuloni.

“This is a chance to confront our history and make sure we don’t make the same mistakes again.”

Judge Carolyn Henwood. Photo: Stuff.

Despite the state having immense powers to intervene in the lives of children and families who are deemed at risk and to impose what can be extreme coercive measures, when the state fails and inflicts harm it goes out of its way to avoid responsibility. All the way through the system, the state controls the mechanisms that hold it accountable. Those mechanisms are weak to non-existent.

Judge Carolyn Henwood quickly became aware of this when she chaired the Confidential Listening and Assistance Service (CLAS), which delivered its final report in 2016.

CLAS had limited terms of reference but Judge Henwood and the panel she chaired heard from more than 1100 people. She was completely astonished by the level of violence — sexual and physical and psychological —inflicted on children by employees of the state. But she was also shocked by the lack of any baseline standards of accountability.

“The first thing I discovered was there was no duty of care articulated anywhere in the department,” she said in a discussion we had at that time, in 2016. “Because that’s the very first thing I thought, I’m a lawyer, I’m a judge, right, so I got on the phone: ‘Where’s the duty of care so I could look at how this fitted with the cases?’

“Much to my astonishment I found there was no duty of care articulated. They said it’s ‘do no harm’. I was astounded, so you could start there. The policy doesn’t have an infrastructure. I think they’re now trying to build this new department. I’m on the edge of my seat wondering whether these issues are going to be dealt with in that department.”

There still hasn’t been any significant answer to her concerns.

There was some hope amongst survivors when the prime minister announced a Royal Commission of Inquiry into abuse in care in 2018.

But two significant developments have now cast doubt on the sincerity of the current government’s intentions. The failures of the Ministry of Social Development and Crown Law to adequately respond to victims of state abuse became the focus on the inquiry’s first major hearing in 2019, which focused on redress. It could be argued that the redress failures were actually the impetus for the inquiry.

The commission’s interim report on redress, which landed in late 2021, made a number of recommendations that were almost banal in their language but were hugely consequential.

Two of the recommendations directly addressed two of major flaws identified by Judge Henwood and others — the lack of a legal baseline standard of protection for children in state custody and the lack of independent accountability. The commission recommended that it should be legislated that children in care should be free from abuse; and if this right was not upheld, the state should be legally liable.

These recommendations seemed particularly crucial when the government came out with the Oranga Tamariki Oversight Bill in late 2021, but there is no indication to date that the government is going to implement these recommendations. The consultation process for the bill was shabby to the point of cynical. It was released a few days before Christmas and the deadline for submissions was late January, which meant many interested parties were caught on the hop in trying to respond.

Despite the short timeframe, there were over 400 submissions that were highly critical of the bill. Legal experts were vocal in declaring the bill a shambles and its intention to split the oversight and care of children across several agencies a disaster in waiting. The Children’s Commission was to be gutted and most of its investigative powers handed off to the Ombudsman. A recently created entity called the Children’s Monitor (responsible for monitoring professional standards) was repositioned under the Education Review Office, compromising its appearance of independence.

But the most glaring gap seems to be the lack of baseline legal standard — as called for by Carolyn Henwood six years ago and reiterated in the redress report in 2021.

The Abuse in Care Royal Commission has suffered budget blow-outs — there were requests for an extension of the deadline and more money. The budget request was knocked back and hearings only extended by six months. Despite this, the Royal Commission will come in with a final price tag to the taxpayer of around $150 million. The government has yet to formally respond to the commission’s redress report, despite the commission asking for feedback by April of this year.

Along the way, the commission’s terms of reference were also tweaked. Initially it could hear evidence about events that took place up until the end of 1999 (the reason for this date was never explained). However, the commission had the discretion to consider evidence after this date, and this discretion remained in the terms changed last year. Now, there is a new clause in its terms of reference, 15d. This clause says the commission “is not permitted to examine or make findings about current care settings and current frameworks to prevent and respond to abuse in care, including current legislation, policy, rules, standards, and practices.” This is contradicted by a later clause saying the commission can make recommendations.

The change in clause 15d also flies in the face of statements the prime minister made when she announced the commission: “This is a chance to confront our history and make sure we don’t make the same mistakes again. It is a significant step towards acknowledging and learning from the experiences of those who have been abused in state care.”

Elison Mae gave evidence at the royal commission. Her face crumples in disgust when the changes to the commission’s scope are pointed out to her.

“If we’re saying historically there’s been an issue, then historically includes what’s happening now. It means that (the government) had no intention of resolving any of this. It means that they can just feel good and tick a box that we created the biggest-yet Royal Commission with the most far-reaching terms of reference, and we don’t actually plan on resolving the issue at all. We’re just going to carry on doing what we’re doing.”

This bureaucratic sleight of hand that cuts out survivors from influencing the future direction of child protection is, like the Oversight bill, Ngahiwi Tomoana’s “misery-go-round” in full swing.

For instance, the shift to delegate more of the functions of Oranga Tamariki has its own risks. One is the question of where legal liability lies if something goes wrong — is the state simply creating a legal buffer for itself by delegating responsibility to third parties?

The push to devolve more funding is sometimes presented by Davis and others as a belated fulfilment of the intent of Te Puao Te Atatu. But the governance and bureaucratic landscape has changed considerably since 1986. The neoliberalism that was abruptly introduced by Roger Douglas has redefined the role of the state in social services to an extent that would barely be recognised by John Rangihau, who chaired the inquiry into the Department of Social Welfare back then.

One of the increasing trends since then is to contract out government services to private entities or NGOs. Child protection, like prisons, has become a multi-million-dollar industry. In the 2020/21 financial year Oranga Tamariki spent $439.3 million on service providers sitting outside the ministry. Of that, $332.3 million went to entities that are non-Māori, while Māori and iwi partners received $106.9 million.

The multinational Open Home Foundation, which provides a suite of social work services, received $22 million in one year for contracts from Oranga Tamariki. It has more access to Oranga Tamariki’s computer system than the Children’s Commission. Other big players are Barnados and Youth Horizons, who also get millions of dollars of taxpayer-funded contracts.

Just like the private prison operator Serco, these entities provide a service on behalf of the state, but in this case, for kids. They are not only dependent on government money to fund their large operations, but they are also dependent on a steady demand for the services they provide.

Oranga Tamariki acting CEO Sir Wira Gardiner raised the topic of NGOs when he met with a group of Māori leaders last year. He mentioned that when John Key was prime minister, he had tried to discipline the NGOs, but they rallied and Key backed down. Gardiner said he had asked Kelvin Davis: “Are you ready for the battle with the NGOs? There will be a fight.”

If Māori are going to take a lead in taking over responsibilities for child care and protection, which Māori are we talking about? The Waitangi Tribunal warned in its report that there was a risk of replacing a state bureaucracy with a brown bureaucracy and “monetising kinship”.

Jean Te Huia has observed that suddenly a lot of people are putting themselves forward as the solution who have no understanding of whānau that are caught up in the child protection system, and have never shown any interest until now.

“We’re going to see the same with the independent Māori Health Authority. You’re going to get people who know nothing about health, that have never been in health who will suddenly be in charge of funding, who will be dictating the terms of health. The same has happened with Oranga Tamariki.”

Who should speak for those who have been through the welfare system? Estimates suggest the number of Māori who went through the state welfare system, including foster homes and welfare homes, is in the hundreds of thousands. Multiplied by their children and grandchildren — who are statistically more than likely to end up in the same system — and the number of Māori who have a family history of state intervention is bigger than any iwi or even several of the biggest iwi combined.

Alongside his Oranga Tamariki and Corrections portfolios, Kelvin Davis is also the minister for Crown-Māori relations. But he draws a blank when asked how victims of state abuse can be represented or engage with Crown when they don’t have the sorts of structures that iwi do and are often in marginalised groups, like gangs and the prison population. “To be honest, I don’t have the answer because it is such a big thing.

“I’m hoping that the Royal Commission will come out with some suggestions.”

Oranga Tamariki, the Royal Commission and state entities have been in the habit of consulting with iwi leaders about historic state abuse or the current failures of Oranga Tamariki, despite iwi leaders being missing in action when victims of state abuse have been fighting against the Crown over decades.

And is there even the workforce capacity to address many of the issues that contribute to children being at risk or the adults damaged by the system they went through as children? The mental health system is already under strain — what if all those who had suffered trauma from abuse in state custody were to suddenly come forward asking for help?

Iwi themselves are also aware of the limits on what they can do and what they can provide. Treaty settlements have been perceived as a panacea to address deep and ongoing inequities, when the settlement amounts are dwarfed by not only the original loss, but also the social and economic needs that have built up over generations.

“We were expected to spend it on all the government’s failures and government’s expectations. Our people expected us to do that too. So that was the dilemma we were caught in,” says Ngahiwi Tomoana, who has close experience of this having only recently stood down as chair of Ngāti Kahungunu after 26 years. He also debated this often with his cousin, Moana Jackson, who observed that the Crown couldn’t follow its own laws, and also had ideas on how that failure could be addressed.

“One thing Moana always used to try and get us to do through Kahungunu was saying the director general of welfare and the chair of iwi will have final arbitration over each child. Jointly.

“He tried to get that in the act. He said if we can get that in the act, that will filter all the way down. But we could never get it in the act. The director general and the successive ministers of social welfare, successive governments, wouldn’t have a bar of it.”

“I have never, ever met a child who was removed from their family tell me that they were better off.”

Rangi Wickliffe spent his childhood in state custody.

Where to from here? With the flaws of the Oversight Bill on full display and the Abuse in Care Royal Commission not yet able to get the attention of the government that initiated it, is there any hope that the misery-go-round could be brought to a halt?

To look to the deeper past, the role of the state as “parent” is built on legacy assumptions about the state’s rights and obligations — the ancient European legal doctrine Parens Patriae assumes that the king is the parent. Down through the centuries that has spread across the world. In some nations, modern governments have apologised for the historic damage inflicted in the name of state “care”. Australia has acknowledged the damage wreaked on its Stolen Generation, Aboriginal children taken into custody by the state.

New Zealand has yet to even acknowledge the damage done, let alone apologise. You know you’re failing when you’re 20 years behind Australia on Indigenous rights.

Māori have always had their own concepts around children and who is responsible for them. Māori children are the embodiment of their ancestors and it is their kin who exercise authority over them. Māori had their own child care and protection system, and it’s not government contractors, it’s called whānau. Wider whānau would assess whether parents were up to the task or were fulfilling their obligations. If there were gaps or they were falling short, other whānau stepped in to fill the gap. If parents were working, others took care of children in their absence. If children weren’t safe, someone would confront the person who was causing harm. I’ve seen a number of examples of this within my own whānau, examples that go unnoticed in the wider public debate. They go unnoticed because, generally speaking, they work.

Intervention is shown time and again to set up certain failure and harm. Rangi Wickliffe, who went through foster and welfare homes and also the notorious Lake Alice, can attest to that. From the age of 16 he spent the next 35 years in and out of jail. “Why is it that every time I see a file it’s about what I’ve done wrong,” he said in evidence to the Royal Commission. “Every mistake is pointed out. Every psychological report written on me points out my bad behaviour. But there’s nothing on there that says anything about what the state has done to me or my family.”

Wickliffe’s case is not an isolated one. It has only been since urbanisation that the state took Māori children in any numbers. Once it started it hasn’t been able to stop. When compared with the taking of Indigenous children in other countries, New Zealand took larger numbers in a shorter period of time, from a smaller population.

But it has never taken full responsibility for the harm those interventions have caused over the last 60- odd years. Instead, it continues to charge ahead with changes and fixes on the assumption that it knows best. But those who have experienced the state’s coercive grip as children know that it doesn’t. And it is their mokopuna who are getting swept up by the state today.

Jean Te Huia is one that has seen that intervention both in her own whānau and in the prisoners she now works with in rehabilitation programmes. At times there was too much alcohol, and violence, in the home she grew up in.

“I believe that as bad as things were at home, our brothers that were removed from our home and put into state care had it worse. Their torment and the abuse that they went through, they can’t come back from. For everything that was bad at home and in our lives, we can overcome that. Because in a way we found the answers ourselves as a family and got stronger.

“We dealt to the alcohol, the abuse, the gambling, the poverty by supporting each other, by supporting each sibling, by holding our parents accountable. By understanding the hurt and the damage that was happening in our home as the oldest siblings. That took years. It wasn’t any overnight thing. Only some of us did. Some of our siblings still went off the rails.

“My boy cousins were also taken into state care as children. Again, abused. I have never, ever met a child who was removed from their family tell me that they were better off.

“All the men in prison that I talk to who have been through the system as children and then been through prison and whose children are now going through it, none of them have told me they’re better off for it.”

Aaron Smale is North & South’s Māori Issues Editor, a role made possible by New Zealand On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the September 2022 issue of North & South.