The Goldfields Gravediggers

Otago’s earliest cemeteries are filled with unmarked graves. Now some of the skeletons are telling their tales.

By George Driver

The gold sluicings at Drybread. Photos by George Driver.

He was tall, walked with a limp and smoked a pipe incessantly. His teeth were terrible. Two had rotted away almost entirely — they must have been a source of constant pain.

He probably grew up in poverty in England and moved to the colonies for a better life. In New Zealand he got scurvy and badly injured his leg. Somehow he made it to Central Otago, maybe during the gold rush. It was the last thing he ever did.

When his body was found, he had been in the freezing Clutha River for some time. His skin had probably turned black and blue from prolonged submersion. Those who found him dragged him up the steep side of the Cromwell Gorge, to where floodwater would never reach, and sent for a coffin from Cromwell, six kilometres away. Word went around, but it seems no one knew who he was.

They did their best in the circumstances. After digging down 130 centimetres in the silty soil, they laid him out in a simple wooden coffin, in the clothes he was found in. His leather boots were still on his feet, the laces doubled around his ankles, secured with a rough knot. They topped the grave with small slabs of schist collected from the surrounding hillside. There was no headstone.

It was a temporary rest, however. The man was exhumed twice over the next century or so — by grave robbers shortly after he was buried; and by archaeologists who dug him up in 1983, ahead of the flooding of the gorge that would follow construction of the Clyde Dam. His bones were then taken to the University of Otago’s anatomy department, but he gave up little information. He sat in a cardboard box labelled E224, on a shelf with others who had been exhumed.

It would take almost four decades before the bones began to reveal the man’s story. He has since become one of the most studied skeletons in the country — we probably know more about his life than whoever found his body. Yet we still don’t know his name. He is one of more than 70 individuals exhumed from forgotten graves in Otago who have been studied in forensic detail as part of a project which is changing our understanding of life and death on the goldfields.

The unknown gold miner’s leather boots were reburied with him this year, the knots in the laces still tied as they were the day he died. Illustration by Imogen Greenfield.

When Hallie Buckley first encountered human remains, on a remote beach on Waiheke Island, it changed her life. She was on an archaeology reconnaissance trip while studying at the University of Auckland, when the students came across bones poking out of the dunes. “There was an incredible, very old Māori settlement there,” Buckley says. “What we came across was an urupa, and a person was eroding out of the sand.”

The class gained permission from the hapū to excavate the person before they were completely exposed. They discovered it was a woman buried with a young child. The remains were immediately reburied further back from the beach, safe from erosion.

While other students later gravitated towards examining artefacts and middens, Buckley focused on skeletons. “I was completely hooked,” she says. “I was always interested in the people themselves and studying them directly rather than looking at how they modified the landscape or what they left behind.”

“The more that you find out about these people, the more that you can humanise them. It’s both fascinating and confronting.”

She began specialising in the field of bioarchaeology. It’s like the CSI of archaeology. Bones and teeth, even fingernails and hair, are analysed to the subatomic level to reveal information about a person’s life and death.

This work took her throughout the Pacific, studying the remains of the region’s earliest explorers. In New Zealand Buckley studied skeletons unearthed at the Waiau Bar in Marlborough, one of the earliest and most important Māori settlement sites. In Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu she was part of a team excavating the oldest known burial grounds in the Pacific, revealing the first explorers who reached the islands 3000 years ago. She went on to study neolithic burials throughout Southeast Asia and today is a professor in the Anatomy Department at the University of Otago.

A decade ago, Buckley turned her attention to skeletons closer to home and nearer the present. On trips to a family crib at Lake Hāwea, she had often wondered how people had survived in the harsh, desertlike environment of Central Otago during the gold rush of the 1860s.

She teamed up with goldfield archaeologist Peter Petchey, who she had worked with in the Pacific. The pair began to plan a new research project on unmarked goldfield graves — the Southern Cemeteries Archaeology Project. While records, artefacts and photos provide detailed information about life on the goldfields, these sources only provide a partial snapshot of who was there and how they lived, Buckley says. Records are often selective. We have stories of officials and diaries from the literate, but women, children, the poor and illiterate are often absent. Information about people’s health and heritage is patchy.

But skeletons don’t lie. Beneath the ground in the region’s cemeteries was what Buckley calls “an untapped source of information” about the gold miners. A kind of census, containing information on where the dead came from, what their life was like, and whether their lot improved as they pursued the promise of the colonies. All she needed was the bones.

University of Otago anatomy professor Hallie Buckley, has spent her adult life studying human remains to help better understand the past.

Otago has no shortage of pioneer cemeteries — often disused, overgrown and all but forgotten. But it’s not easy to get permission to dig up the dead in New Zealand.

While bodies have been exhumed, unearthed by urban development or erosion, no one had dug up a graveyard for research before. It didn’t start smoothly. Buckley and Petchey’s planned inaugural dig at Moa Creek Cemetery in Central Otago’s Ida Valley fell through in 2015 due to opposition from some of the community. Some locals didn’t like the possibility that their relatives might be dug up and studied, even if the location of their graves had been lost. Or as one opponent, a Cromwell resident, put it at the time: “I believe that those areas are classed as sacred and man’s body and soul belong to God and it is not for us to intervene.”

But the following year, a community group restoring a cemetery in Milton approached Buckley and Petchey and invited them to help identify unmarked graves, and to find out who was interred within.

Not quite a gold-rush town, not quite Central Otago, Milton began as a rural settlement on the Taieri Plains in 1850. St John’s Anglican Cemetery began operating a decade later, just a year before the Otago gold rush began. People were buried there for 66 years before the cemetery was closed.

The project gained approval from Heritage New Zealand, and the Ministry of Health granted a disinterment licence in 2016. By December, a 13-tonne digger was peeling back the topsoil to reveal multiple long-forgotten graves. Some were outside the bounds of the cemetery entirely, on neighbouring farmland. One was intersected by a farm offal pit.

Over the following weeks, Buckley, Petchey and a team of students found 25 unmarked graves and the remains of 27 people — 11 infants, four children, one teenager and 11 adults. Some could be identified immediately. One woman had her name written on her coffin lid. A local researcher was able to read out her brief biography to the researchers as her body was exhumed. For Buckley, used to dealing with remains of anonymous people who died thousands of years ago, the experience was far more immediate.

“Everyone really did feel that this is a person who is known, rather than somebody in the distant past,” Buckley says.

Another Milton man was later identified as gold miner Joseph Higgins, who died in 1877 after the mine shaft he was in collapsed at Canada Reef, 12 kilometres west of the township. The team was able to match the injuries on the skeleton with news reports of the incident.

“We discovered his father-in-law was underground with him when he was killed,” Petchey says. “He got out, but would have had to go and tell his daughter that her husband was dead. You can begin to picture the immediacy, the visceral reality of it.” Some graves were sodden and preservation was variable, however. For the infants and children “only teeth and hair were present”, as one paper on the project describes. Others were “represented instead by just shadows in the soil”. Many remain anonymous.

A year and a half later, the project expanded to Lawrence (again, at the local community’s request), where the Otago gold rush began when Gabriel Read struck gold nearby in May 1861. The team excavated two cemeteries there. The first had begun with the gold rush and closed in 1866 — the gravediggers kept hitting bedrock. All but one of the graves on the site — now private land — were believed to have been exhumed and moved to the “new” cemetery nearby, but the team found 24 people buried there, including possibly some of the first Chinese miners.

A further 27 unmarked graves were found in the Chinese section of the new Lawrence cemetery, though all but nine had been exhumed earlier. Most had been dug up to be repatriated to China for cultural reasons in 1883 and 1902. The latter journey was never completed. The steamship Ventnor, carrying the remains of 499 Chinese miners, sank off the Hokianga Harbour after hitting a reef.

The final phase of the study began in 2020, when the team headed to Drybread Cemetery, in a gold-mining ghost town at the foot of the Dunstan Range, 12 kilometres north of Omakau in Central Otago. The cemetery has been in continuous use since the 1860s, but over the years the location of some graves had been lost. The trust managing the cemetery wanted to ensure that when they dug down to bury the next person they wouldn’t find a century-old coffin.

The project team exhumed 12 people at Drybread, including another six Chinese miners.

In all, the remains of 72 people were taken to the University of Otago anatomy lab to be studied in forensic detail.

Anatomy and forensics lecturer Charlotte King, above, is an expert on the chemical makeup of human tissue and what that can tell us about the lives of the dead. Photo: Graham Warman.

Archaeologist Peter Petchey, above, says life on the goldfields “wasn’t hell on Earth, but was probably a tough life for everyone by our standards”.

Charlotte King leads me into the bowels of the austere concrete tower of the University of Otago’s Richardson Building. We continue past rows of shelves containing fossils, rocks — I spy a horse’s skull. Eventually, we end up in a room little bigger than a closet. On a small bench, vials contain what look like small flakes of polyethylene foam. It’s collagen, King explains, derived from the bones of some of those exhumed from Drybread Cemetery.

King has been involved in the Southern Cemeteries project since 2018. Before that she studied Incan mummies exhumed in Chile’s Atacama Desert. While Buckley’s work mainly involves studying the surface of the bones and teeth, King — an anatomy and forensics lecturer — is an expert on the chemical makeup of human tissue and what that can tell us.

When the human remains first arrive in Dunedin they are taken to the university’s anatomy department and laid out on benches to slowly dry. They are then put into small cardboard boxes and stacked on shelves that rise to the roof at the back of a room that doubles as an office for PhD students, though skeletal remains of Māori ancestry — kōiwi tangata — are housed separately in their own wāhi tapu.

It’s an unconventional working environment. King says they have strict protocols in the room, including no food and drink. Even when working daily with the skeletons, she tries not to become desensitised to what’s involved.

“I think you can’t let it become normal,” King says. “Because it’s still a person. That’s in my mind the whole time. And the more that you find out about these people, the more that you can humanise them. It’s both fascinating and confronting.”

He had lesions on his skeleton suggesting he had scurvy, possibly during the early days of the gold rush when fresh fruit was hard to come by.

In the anatomy lab, small flakes of tissue are removed from the skeletons and taken to King’s cell-like lab to be cleaned, prepped and refined — like the collagen samples she showed me. Then they go over to the chemistry lab. In strictly sterile rooms — think hair nets, lab coats, booties and sealed doors — the human tissues are dissolved and the elements are isolated before being fed into a machine to determine the presence of different isotopes.

Your teeth, bones, hair, fingernails, even dental plaque, contain a chemical signature which broadly records where you were and what you were eating when those tissues were formed.

King primarily studies the isotope ratios of four main elements: strontium, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. Strontium is an element that’s a key component of rocks and has a different ratio of isotopes depending on how old the rock is. As rocks erode into the soil and are absorbed by plants, this isotopic ratio is retained. When someone eats the plants — or eats the animals that ate the plants — that same ratio becomes locked into their tissue, recording the geology of the area they were in (well, at least for those who lived before the globalisation of food production). By comparing the strontium ratios found in the tissue with the geology of different sites around the globe, King is able to determine where a person likely was when that tissue formed.

Oxygen isotopes, meanwhile, record information about the climate a person was in, as the isotopic ratio in water differs depending on whether an area is dry or wet, warm or cold.

Carbon and nitrogen isotopes, meanwhile, leave a signature of the type of plants and animals a person was eating. This can tell researchers whether their diet was rich in meat and the types of vegetables they were eating. The isotopes can also record stress — whether a person was starving and metabolising their own tissue.

As teeth, bones and hair form at different times and different rates, these record a person’s diet and approximate location in different periods of their life. Hair, for example, grows at a rate of a centimetre a month and so leaves a record of a person’s health and location in the months before their death.

Then there’s DNA. Buckley says while it’s helpful for providing information on a person’s background, it’s not as useful as people might think. Getting a detailed picture of a person via DNA requires the remains to be exceptionally well preserved, and sequencing the full genome is very time-consuming and expensive. “It’s not a magic bullet for identifying people,” Buckley says. The researchers mainly analyse mitochondrial DNA, which provides a person’s mother’s genetic history, meaning a link can be made to the part of the world in which this DNA is most commonly found.

12 people, including six Chinese gold miners, were exhumed from unmarked graves in Drybread Cemetery as part of the project.

The analysis is still ongoing, but a picture of those exhumed is beginning to emerge.

And it sounds rather bleak. Childhood mortality was high. Most people appear to have experienced periods of severe stress from a lack of food or illness, particularly during childhood and the early stages of the gold rush when supply chains were limited and produce was seasonal.

In Lawrence, most people also have mercury in their tissue — a poisonous substance used to extract gold from dross, but also taken as a medicine for everything from period cramps to venereal disease. “Everyone’s slightly suffering the chemical effects of living on the goldfields,” King says. Everyone also has horrendous teeth — massive cavities, abscesses and ulcers which would have been a nagging source of pain.

Despite the challenges, life for most miners seems to have been a bit better than where they came from. A diet including fresh meat was a big selling point for the colonies in the mid-1800s, and broadly appears to have delivered.

Interestingly, King says the Chinese miners show a more marked improvement in their diet after moving to New Zealand. Their diet appears to have been better than the miners who came from Europe, while their upbringing was more challenging.

“They’re growing up in Opium Wars [era] rural China, where they were incredibly marginalised by different regimes,” King says. “But on the goldfields they also seemed to have worked as a community a lot more than the Europeans and provided for each other.”

Most miners were British, as was expected, but what struck King is that they came from right across the isles, and also Western Europe. “Even in England at the time there are vastly different regional cultures and I’ve never seen the amount of variation we get in the goldfields in any other location.”

While it was assumed by historians that all of the Chinese miners came from Guangdong province (formerly Canton), many had chemical signatures from elsewhere in China — one had DNA most commonly found in the islands of Southeast Asia. Another had European maternal ancestry — although it’s impossible to tell how recently. “The complexity of these people’s identities is something we never realised,” King says.

Peter Petchey and a team of archaeology students have been searching for the lost gold mining town of Drybread in Central Otago as part of the project. They recently found the remains of a house with an ornate garden and fragments of children’s toys, suggesting a more domestic life than typically associated with the goldfields.

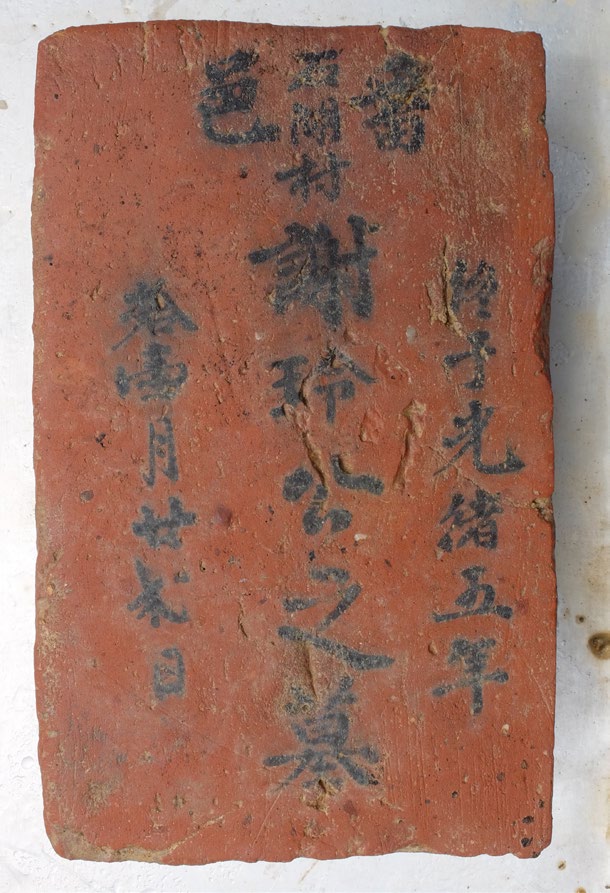

A brick inscribed with Chinese characters found in a Chinese grave in Lawrence. The body had already been exhumed to be repatriated to China. The tablet includes the name of who was buried in the grave and where they came from.

As work was underway to excavate the cemetery in Milton, Hallie Buckley’s attention was drawn to the man exhumed in the 1980s near Cromwell and labelled E224 — the man buried with his boots on.

Buckley had known about E224 since she moved to Otago as a post-grad student 25 years ago. He had been a subject studied by a generation of post-grad students. Now she began to wonder what else the man could reveal about life on the goldfields.

Fortunately, E224 was particularly well preserved. Over the course of two years, Buckley and Petchey’s research team began to piece together a picture of his life. The man came from an area with chalky-limestone geology — likely southeast England or Ireland. Like many in early industrial England, he appears to have grown up in poverty. His tooth enamel hadn’t developed properly when he was a child, meaning he likely suffered from malnutrition, or was very ill for a long period. But things got better. In adolescence his protein consumption increased, possibly as he entered the workforce.

Despite a challenging childhood he was tall, particularly for the time — about 188 centimentres. It’s not clear when he came to New Zealand, but at the time of his death he would have been about 40 and carrying a number of ailments from what must have been a rough life.

He would have been in constant discomfort from rotting teeth. The man also had what’s called pipe facets — a groove worn between two teeth from years of having a tobacco pipe wedged between them. It’s a feature shared by all of the males exhumed as part of the project — and even some of the females.

His shoulder had a defect which probably made it sore and stiff to move. He had also injured his ankle at some point, which likely required months of care and probably left him with a limp. He had lesions on his skeleton suggesting he had scurvy, possibly during the early days of the gold rush when fresh fruit was hard to come by and almost everything had to be carted in from the coast.

The smell would have been horrendous for the graverobbers, head down in a hole in the dark. “Whoever it was had a strong stomach and few qualms.”

Despite the detail, there are still a lot of uncertainties. It’s impossible to tell definitively what he was doing in the area when he died. Given the time period, it’s likely he was a gold miner, but he could have been in the area for numerous other reasons.

It’s not exactly clear when he died, and his death was too recent to be able to be radiocarbon dated (that works on remains 500 years or older). The coffin appears to be from the early gold rush period, but it may have been a decade or two later. Even his death is only assumed to be by drowning, but it seems likely given the location and circumstances of the burial.

For Petchey, it’s what happened after his death which is most interesting. One or two people appear to have dug down into the grave one night shortly after the burial and smashed through the coffin lid. The shovel went straight through the body, leaving a mark on the corpse’s pelvis.

When they went to pull the body out to search it, perhaps days after his burial, it appears to have come apart — decomposition must have been well advanced. The smell would have been horrendous for the graverobbers, head down in a hole in the dark. “Whoever it was had a strong stomach and few qualms,” Petchey says.

Some body parts were left at the side of the grave and hastily buried under a few centimetres of soil — perhaps the graverobbers were disturbed and bolted. The rest of the body was left inside the coffin, until the archeology team led by Neville Ritchie found him in 1983, prior to the area’s flooding by the Clyde Dam.

Exactly why his grave was robbed is a mystery. It would seem unlikely that a body found in the goldfields wouldn’t be stripped of valuables before burial. Petchey speculates that the scheme was hatched late in the night after a few drinks at the nearby Halfway House Hotel in the gorge, perhaps roused by a rumour the man was buried with gold.

While it reveals one of the darker sides of the gold rush, Petchey says it also shows a sense of community and decency. People went to some effort procuring a coffin from Cromwell, and covering the grave in schist slabs, ensuring the stranger had a proper burial.

In a dimly lit room adjoining a tavern in Alexandra, a pair of old leather boots sat atop a simple pine coffin with rope handles. A brass plate on top simply said “The Gold Miner”.

The research complete, in May, E224 was finally reburied.

When funeral director Lynley Claridge read in the local paper that the unknown miner was to be reinterred in Cromwell, she wanted to ensure he got an appropriate send-off. He was laid out at the funeral home when I went to pay my respects. “I just felt I needed to bring him home,” Claridge told the Otago Daily Times.

It’s unlikely there was much of a funeral when he was first interred. But more than 140 years later the unknown man had become something of a local celebrity. Hundreds turned up for a funeral that was live-streamed around the world, and featured on the evening news. The following Monday it made the front page of the Otago Daily Times.

For many, E224 became a symbol for all of those who died during the gold rush era and have since been forgotten, “whose names are known to God alone”, as Reverend Barry Entwistle said at the service. There will be more funerals soon. Eventually, once the research is complete, all of the people disinterred as part of the Southern Cemeteries Project will be reburied.

“For some communities it’s really important to recognise their existence and allow them to rest,” Charlotte King says. She says that respect and closure is important for her too.

“As scientists we don’t always think about the spiritual aspect of what we’re doing, but in this project it’s something we’ve been really conscious of. We’re not just grave robbers.”

The coffin of the unknown gold miner was drawn in a horse and cart through Old Cromwell, followed by a procession of people in period clothing.

More than 100 people turned up for the funeral of the unknown gold miner in Cromwell, which was livestreamed.

George Driver is North & South’s South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by support from NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the September 2022 issue of North & South.