Culture Etc.

Above: After the Thomas Burns memorial was demolished, plans for a new memorial failed to gain interest. Today this modest plaque in front of First Church is Dunedin’s only public memorial to the poet’s nephew. Photo: Thomas McLean.

Almost Famous

Though they never ventured south of the equator, four literary giants have unexpected links to Aotearoa — some more celebrated than others.

By Thomas McLean

Robert Burns, John Keats, Charlotte Brontë, James Joyce — any list of the English language’s most important writers would surely include these four figures. None of them ever travelled outside Europe; yet all four have intriguing associations with New Zealand through family and close friends who came here, leaving their own marks on their adopted homeland. For some of these immigrants, their Antipodean experience was closely tied to the brilliant writer in their lives; for others, the connection was purposefully avoided.

New Zealand’s most famous literary association is with the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Readers still thrill to the midnight ride of Tam O’ Shanter, quote lines from “To a Mouse” (“The best-laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men . . .”), or ring in the New Year with Burns’s version of “Auld Lang Syne.” Many visitors to Dunedin’s Octagon pose with Sir John Steell’s bronze statue of Burns without realising that his nephew, the Reverend Thomas Burns, was one of the city’s founders.

Thomas was only three months old when his uncle died in 1796, and the temperaments of the two — one a conscientious Presbyterian minister, the other an earthy poet — seem as distant as Scotland is from Aotearoa. And yet, Robert Burns also considered leaving his homeland for the colonies; though, in his case, it was to take a position on a sugar plantation in Jamaica. One wonders how admired the poet who wrote the radically egalitarian words of “A Man’s a Man for a’ That” would be today had he made a living overseeing the work of enslaved Africans. Only the unexpected success of his 1786 collection Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect allowed Burns the means to remain in Scotland.

Thomas Burns was himself a remarkable man. He gave up a comfortable living to join the Free Church secession from the Church of Scotland, then led his flock to the other side of the world. Departing in November 1847, they travelled for nearly five months on the Philip Laing from Greenock, Scotland to Port Chalmers, founding the first Scottish colony in 150 years. Later he helped establish both Otago Boys’ and Girls’ High Schools, and served as the University of Otago’s first chancellor.

In his lifetime, Thomas Burns lived in his uncle’s shadow. The first Burns Supper in honour of Robert in Dunedin took place on 25 January 1855. Thomas Burns was apparently not present.

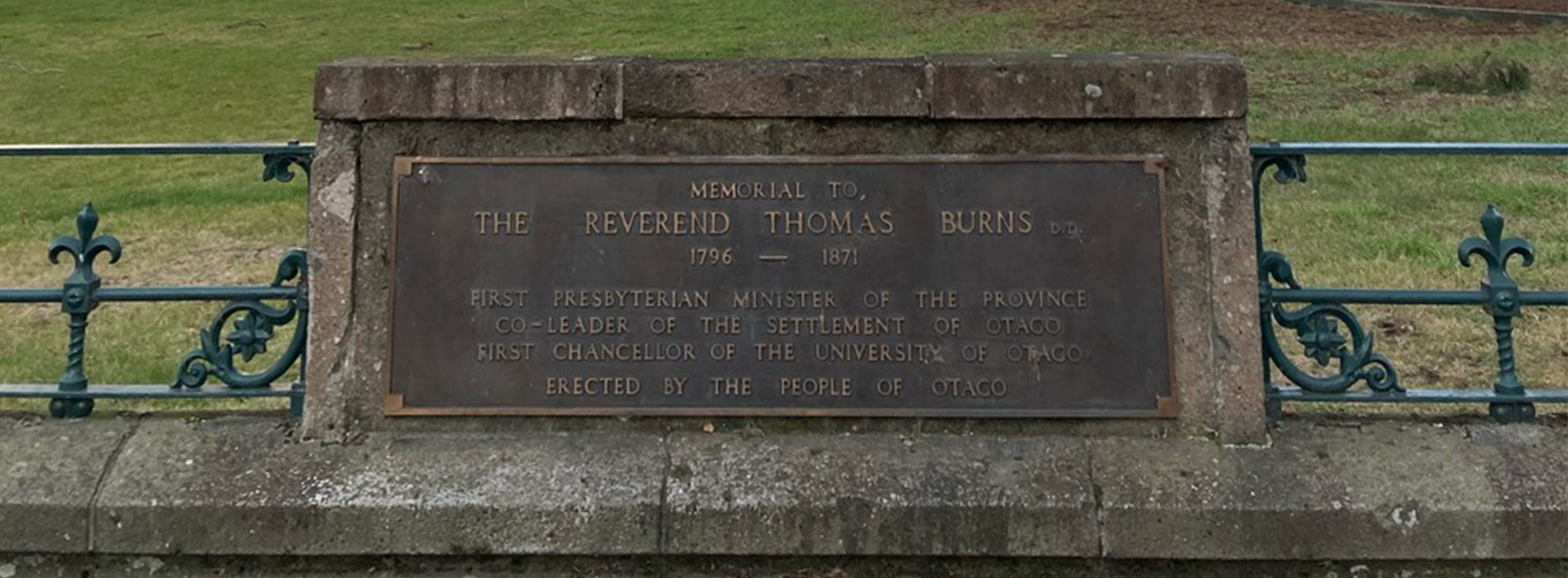

Photograph of the Reverend Thomas Burns, probably taken in the 1860s. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Yet even in his lifetime, Thomas lived in his uncle’s shadow. Burns Suppers, celebrating Scotland’s national poet on his birthday, had begun in his home country only a few years after the bard’s death. The first Burns Supper in Dunedin took place on 25 January 1855. Thomas Burns was apparently not present.

From 1892, a memorial to Thomas Burns stood at the lower end of the Octagon, vying for attention with Steell’s statue of the poet. But it was demolished in 1948 — just a few days after the centennial of Thomas Burns’s arrival. At Toitu Otago Settlers Museum, a formidable image of the minister looks down on visitors to the portrait gallery. But nearby, his uncle gets a display case all to himself. Here, and in Dunedin’s City Library, visitors can see relics including a snuff box supposedly owned by the poet and a slab of timber purportedly taken from the Auld Brig of Ayr.

Yet the spirit of Thomas Burns should take solace: his many achievements continue to shape Dunedin. As for his uncle — well, several years ago the University of Glasgow Burns scholar Gerard Carruthers examined the city’s collections, and declared Dunedin the proud owners of one of the finest gatherings of fake Burns memorabilia he had ever seen.

Many readers of the English poet John Keats make their way to New Plymouth, in search of Keats’s friend Charles Armitage Brown. Brown shared his Hampstead home with Keats in 1819, when Keats wrote many of his best poems. It was Brown who (at least by his own account) helped Keats turn a pile of inspired scraps into his famous “Ode to a Nightingale”. Early in 1820, Keats coughed up blood and feared for his life. He departed London for the warmth of Italy in September 1820, but a tumultuous journey, followed by 10 days’ quarantine in Naples, left him broken. In his last surviving letter, written from Rome on 30 November 1820, Keats told Brown, “I can scarcely bid you good bye even in a letter. I always made an awkward bow.” In February 1821, Keats died from consumption—that is, tuberculosis. He was 25.

Few would have predicted Keats’s posthumous fame. The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (Mary’s husband) was one; he wrote his famous elegy “Adonais” in honour of Keats. But Brown was another. In 1835, he moved with his son Carlino to Plymouth, England and wrote a memoir of the poet. In 1841, the pair left England as part of the settlement of New Plymouth.

Carlino Brown became a key figure in the colony, serving in the New Zealand Army and in Parliament. His father was less fortunate. “The Plymouth New Zealand Company have grievously disappointed us,” he wrote to a friend in early 1842. He was angered at the distance from the port to his assigned lot of land and had planned to return to England immediately, before dying of a stroke that June.

Brown had brought all his worldly possessions with him to New Zealand — including his mementos of Keats. Perhaps, had Brown found New Plymouth more to his liking, it might today be home to one of the world’s great literary archives. Instead, Carlino and his descendants returned most of these items to England, donating many to the Keats House Museum in Hampstead, the same building where Keats and Brown once lived, and where Keats was inspired by the nightingale’s song.

Reminders of Brown and Keats do survive in New Plymouth. Part of Brown’s library is in the Puke Ariki collections, including a copy of Tasso that scholars believe was among Keats’s books in Rome. And Brown’s grave can be found in a leaf-strewn corner of Marsland Hill, behind St Mary’s Cathedral. A simple plaque reads, “Charles Armitage Brown. The Friend of Keats.”

Several years ago, Dr Grace Moore and I identified a single-page manuscript in the Dunedin City Library as being a missing page from one of Branwell Brontë’s stories. Branwell was brother to the most remarkable sibling novelists in British history: Anne, Emily, and Charlotte. This single page remains the only known Brontë manuscript in Australasia. It’s possible, however, that somewhere in Wellington many more Brontë letters survive.

Charlotte Brontë, author of Jane Eyre, kept up a long correspondence with her childhood friend Mary Taylor, who moved to Wellington in 1845. Mary’s brother William Waring Taylor had immigrated several years earlier and set up a successful import company. When Mary left Britain, Brontë was heartbroken: “To me it is something as if a great planet fell out of the sky.” In her 1849 novel Shirley, Brontë fictionalised her friend’s travels through the character of Rose Yorke, who disappears from the narrative “a lonely emigrant in some region of the southern hemisphere,” living in a “virgin solitude” where “unknown birds flutter”. Brontë was right about the birds but wrong (on many levels) about the solitude.

Had Keats’s dear friend found New Plymouth more to his liking, it might today be home to one of the world’s great literary archives.

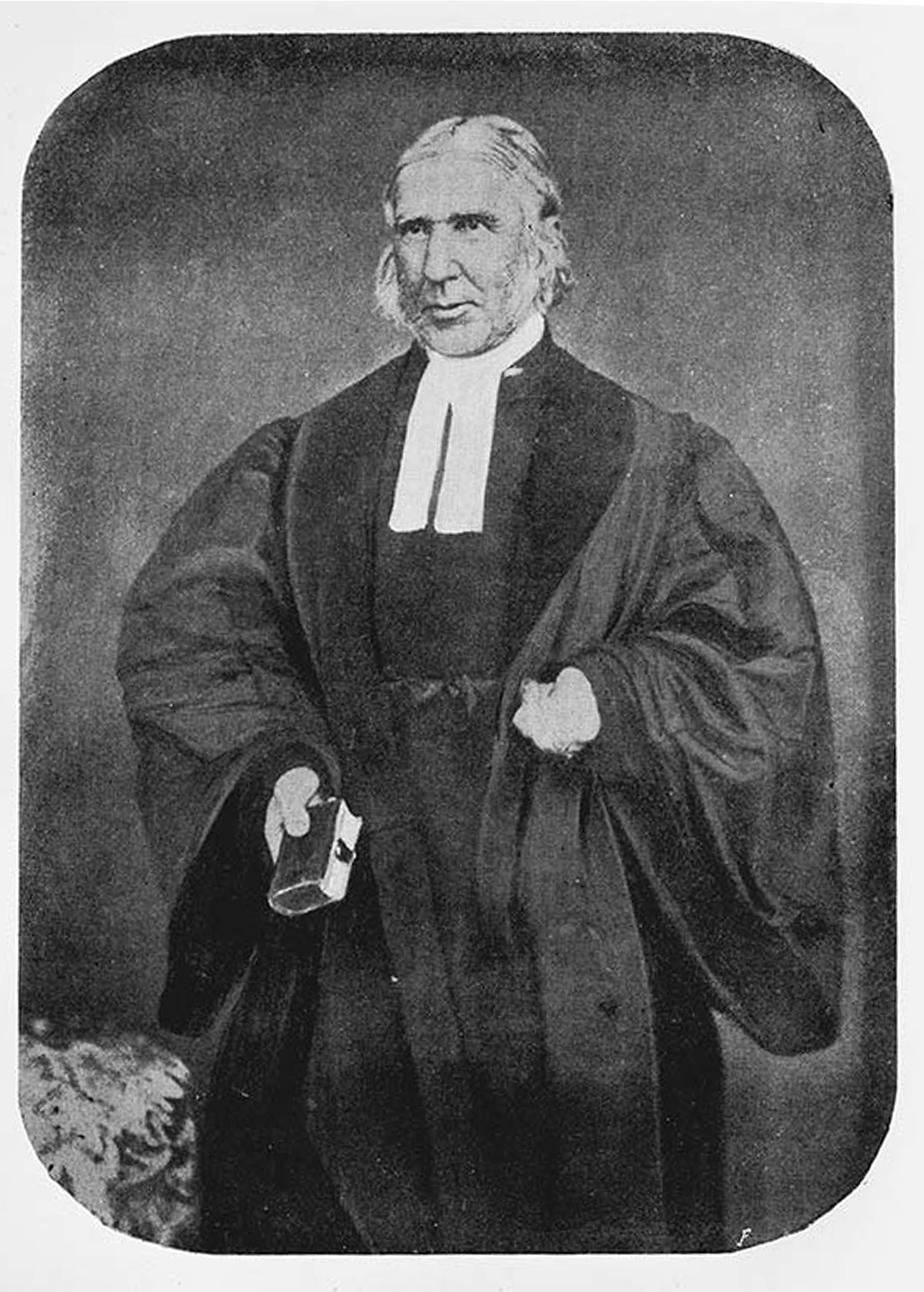

Charles Armitage Brown’s 1819 sketch of John Keats was donated by his granddaughter to London’s National Portrait Gallery in 1922. It became one of the most famous images of the poet. Photo: Hocken Collections.

Mary flourished in Wellington, finding opportunities that escaped her in Yorkshire. Surviving city fires and a major earthquake, she ran a successful clothing and drapery shop with her cousin Ellen on the corner of Cuba and Dixon Sts. She also hoped to follow in Charlotte Brontë’s footsteps. In March 1851 she wrote to a friend, “I have told people of my acquaintance with the writer of J. Eyre & gained myself a great literary reputation thereby.” After she returned to Britain in 1859, she published articles encouraging women to work for independent means; co-authored with four women a travelogue of Switzerland; and, in her final years, published a proto-feminist novel, Miss Miles, that she almost certainly began in New Zealand. By contrast, her brother, who had started off so well in his adopted homeland, ended up in prison for financial fraud. Wellingtonians, is it time to rename Waring Taylor St?

Taylor and Brontë seem to have maintained a healthy exchange of letters until Charlotte’s death in 1855; however, only a handful of Mary’s letters from the period survive, and only one from Charlotte — a treasure trove of a letter, in which she describes the famous trip taken with Anne to London to identify themselves as Acton Bell and Currer Bell (the gender-ambiguous pseudonyms they published under). Some scholars still hope that a long-lost cache of Brontë letters will show up at a North Island car boot sale — and perhaps an equally interesting collection of Mary Taylor letters at a Yorkshire auction house.

The only known photograph of Mary Taylor, taken in her later years.

A portrait of Charlotte Brontë, right, by family friend John Hunter Thompson, probably made after the author’s death in 1855. Image: Bronte Parsonage Museum.

Scholars have less hope for discovering a cache of James Joyce letters in New Zealand, although like Keats there was a time when such a collection existed here, thanks to Joyce’s sister Margaret Alice, known as Poppie. “Poppie will be here tomorrow on her way to New Zealand,” Joyce wrote to his brother from Dublin in November 1909. At the time of her departure, Joyce had published book reviews, a collection of poems, and a few stories. But he had written all the stories for Dubliners and was searching for a publisher brave enough to print them. One of those stories, “Eveline”, concerns a young woman torn between her desire to leave Ireland for a life abroad, and her deathbed promise to her mother to stay and care for her younger siblings and abusive father. Scholars have long seen Poppie as an inspiration for Eveline (who is nicknamed “Poppens” in the story).

Eveline longs to travel to Buenos Aires with her sailor lover. Poppie’s desire was to become a Sister of Mercy. She did so in 1909, taking the name Sister Mary Gertrude, and emigrating to New Zealand to serve the Greymouth community. From 1949, she taught at Loreto Preparatory College for Boys in Papanui, Christchurch until just a few weeks before her death in 1964.

There is some evidence that Poppie stayed in touch with her writer brother, whose fame and notoriety grew with the publication of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses. However, all of her personal correspondence was, according to her wishes, burned after her death. Still, thanks (perhaps) to his sister, Joyce’s interests in Māori culture and New Zealand rugby made their way into his last and still bewildering work, Finnegans Wake. Joyce was in Paris when the All Blacks (on their “Invincibles” tour) defeated a French Selection on 11 January, 1925 at Colombes Stadium. Though there is no evidence that Joyce attended the match, a scrambled transcription of the haka performed only on that tour appears in Finnegans Wake. One obituary of Sister Mary Gertrude Joyce claimed that her brother had written to her asking for the Māori and English versions of the haka.

For her part, Sister Mary Gertrude had no interest in reading Joyce’s later works. But several interviews given late in life suggest that she retained fond feelings for her brother. As she told one interviewer, “Jim was a lovely boy to me.”

Portrait of James Joyce, 1934 by Jacques-Emile Blanche. Image: Courtesy of National Gallery of Ireland.

Thomas McLean teaches English at the University of Otago.

This story appeared in the September 2022 issue of North & South.