Culture Etc.

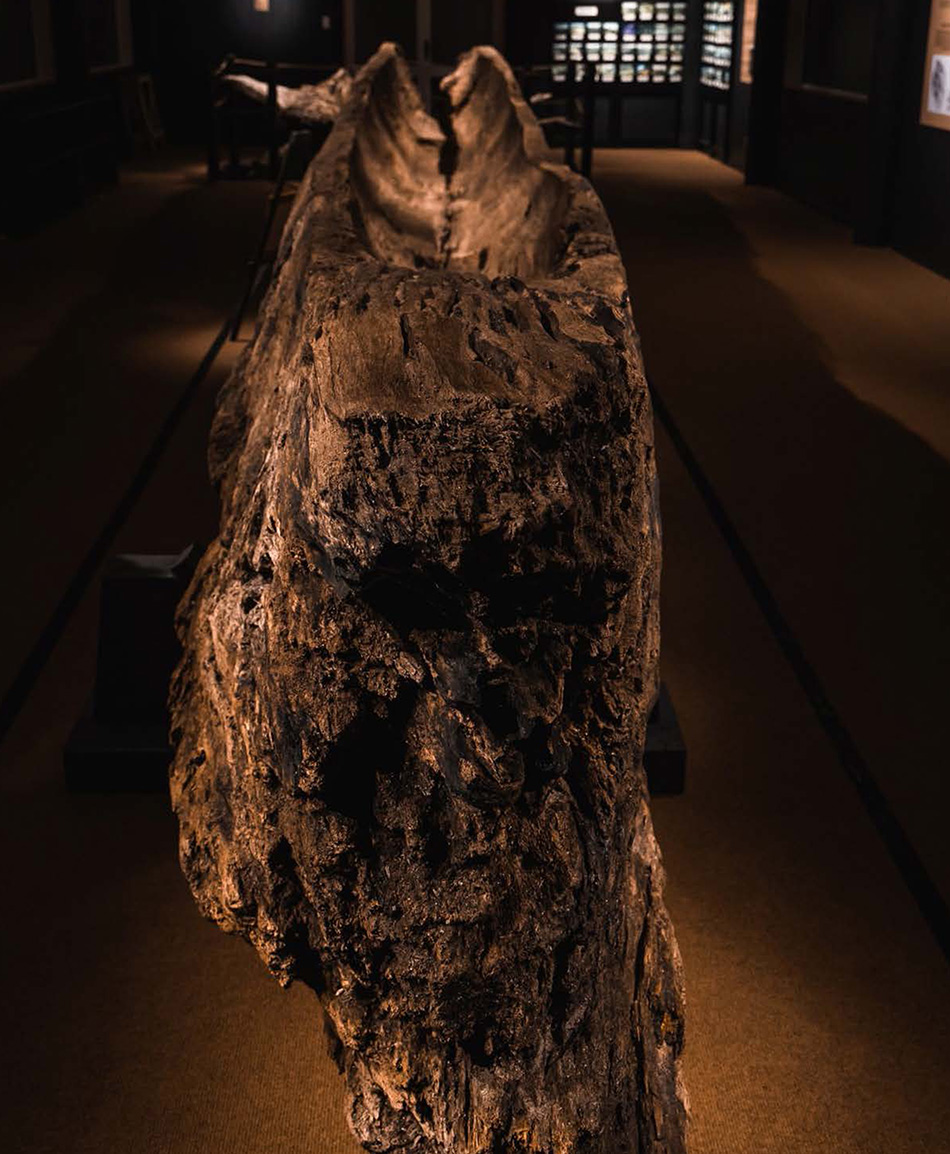

Above: Te Wao Nui o Tāne, an historic artefact Amanda Kiddie found so moving that she ended up joining the museum’s board as treasurer after seeing it.

The Living Museum

A prized exhibit at a much-loved small-town museum receives a makeover from volunteers keen to keep the Waikato’s history alive.

By Taualofa Totua

In 2002, a 13-metre-long, partially built totara waka was unearthed from under sand and gravel at a quarry on Rangiatea Rd in Ōtorohanga. At one end, the hollowed trunk comes to an aerodynamic point; at the other, gnarled roots reach outwards. Called Te Waonui o Tane, it’s believed to have been buried up to 200 years ago, possibly during a major flood that destroyed the village where the quarry lies. Time has accentuated its grain.

After four years of careful restoration, the waka became the centrepiece of the Ōtorohanga Museum’s collection and is displayed in the museum’s only contemporary building, which was purpose-built in 2006. The rest of the museum includes a courthouse built in 1912, the St Brides Anglican Church dating back to 1908, and a 1896 police lock-up and office.

In the north part of King Country or Te Rohe Potae, Ōtorohanga Museum is a custodian of the town’s history, genealogical records and other taonga.

Nan Owen, 94, who ran the place for 20 years and remains a patron, still likes to pop by on a near-daily basis. When she moved to Otorohanga from Auckland in 1950, Owen worried the town’s rich history was being lost. She began collecting items that in some way had contributed to the development of Otorohanga, and life within it. One of Owen’s daughters remembers her mother rushing around garage sales on Saturday mornings to acquire items for the museum. Other childhood memories might be stirred in the courthouse, where toys of yesteryear are on show. Owen’s collection is enormous: typewriters, pounamu, flour sacks, Crown Lynn swans and carvings are displayed on shelves and in cabinets. Hanging on the walls are framed aerial photographs, a collection of kete, and old Four Square signage. “It’s a much-loved museum because we just do the local history,” Owen says. “We don’t do things that are not related to the local town.”

Still, one particular item has caught the eye of our national museum. It may appear to be an ordinary old wheelbarrow, but it marks a historical turning point. In 1882, Ngāti Maniapoto agreed to a survey for a railway line through the King Country. Three years later, on the bank of the Pūniu River, this wheelbarrow held the first sod dug up for its construction. The railway line unlocked the region to Pākehā settlement, for better or worse. Te Papa have asked to borrow it a number of times, says Owen, but each time she has politely, and firmly, refused. The wheelbarrow is too precious to the local community to be put anywhere else, she says. A small padlock secures its iron wheel to the floor.

Collections of historic artefacts can be seen on display and through the building’s recently repainted windows. The committee’s cultural advisor, Pera MacDonald, is pictured (top). Colin Murphy (above), inspects the waka. All photos: Maea Media.

Volunteer and museum treasurer Amanda Kiddie says Owen’s magpie tendencies have stopped significant pieces of the town’s history from being thrown in the bin, including years of minutes from nearly every business and association meeting in Ōtorohanga. Since 2020, the museum has digitised all the handwritten documents in its collection, a process that Kiddie says has made missing pieces of history available to the community.

The very existence of the museum is the result of hard graft by committed locals. Its central building, the courthouse, was destined for demolition in 1974. These plans were met with stubborn resistance from long-time local Bill Millar, a man who knows everyone in town. “I have a passion for promoting our town,” he says.

Passion is a widely overused word these days, but in Millar’s case it actually seems accurate. He was part of the public relations group who championed the town to locals and visitors, raising money in part by selling glass to recyclers. Volunteers would collect wine bottles from the hotel, and on Sundays scour the dump for other glass containers like medicine jars and vinegar bottles. With the earnings, they bought the courthouse for $100.

The next challenge was moving the building. A trailer had been made for the occasion by Darcy Lupton, a resourceful local engineer, out of rolled steel joists usually used for structural streelwork. It was towed along Ballance St, where it sat by the Police station, down Turongo St and then Kakamutu Rd, where it was backed into its current position opposite the park. “We made sure that the traffic officer was out in the country,” Millar says. “Or perhaps he turned a blind eye.” Historical in its own right, the courthouse became the first building for the museum.

Ōtorohanga Museum used to be open just one day a week, but has recently increased its hours to four days (though only from noon to 3pm in winter), and for the first time now employs both full and part-time workers. Each of the museum’s exhibitions includes a kind of treasure hunt — children are encouraged to play with objects painted yellow. The museum is big on play in general, and has chickens for feeding, (unloaded) rifles to take aim with and a kitchen to play-act cooking in. “We are never going to be behind glass,” Kiddie says. “We are encouraging everybody to touch, to feel. That’s the best way of learning.”

The whare housing the waka was closed at the start of the pandemic. During the following down time, the exhibit was given a makeover, and the museum team has been busy, combing through collections; unpacking, reorganising and cleaning. When the waka whare reopens lights will illuminate the unfinished waka. The exhibition will feature stories that honour and represent the surrounding iwi. Kiddie describes how moving it is to sit at the base of the waka, feeling the power of this majestic piece of history. “ Most people have seen a waka, but there is something special about our waka,” she says. “When I need time to think or if I am upset, I will go and sit and rest my head against it.” She hopes visitors will experience the same feeling of connection.

The museum committee has worked hard to remind the town that the museum belongs to everyone. At a recent Anzac exhibition, one visitor discovered that a medal on display had belonged to her great-uncle who had fought and died during World War I. “Her dad, who was 88, can still remember his uncle,” Kiddie says. The museum returned the medal to their family.

Ōtorohanga Museum, Ngā Whare Taonga o Ōtorohanga

15 Kakamutu Road, Ōtorohanga. otorohangamuseum.co.nz

Standing under a trio of flags, is local Mayor Max Baxter and National Party MP Barbara Kuriger. All photos: Maea Media.

Taualofa Totua is a The Next Page intern, supported by NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.

This story appeared in the November 2022 issue of North & South.