The Virus Hunter

By choosing a career in science over dance, evolutionary biologist Jemma Geoghegan may have saved your life.

By Paul Gorman

Photo: Nico Penny

“It’s strange, I guess, coming off a plane from Scotland and arriving in Dunedin, where there’s lots of Scottish references and the Robert Burns statue and things like that,” says Geoghegen, pictured on the Otago Campus, “the people are quite similar, quite relaxed.”

“Ask her about the time she had to collect samples of whale snot from their blowholes,” Jemma Geoghegan’s colleague Joep de Ligt suggests.

Being a virus hunter can take you into interesting places. In this case, the winter waters 3km off the coast of Sydney, sailing in as close as 20m to pods of eastern Australian humpback whales, to be able to launch a drone bearing a petri dish that can be opened and closed remotely.

“When they came up for air, we would just fly the drone, open the petri dish, go through the snot, close it again and then bring it back to the boat,” says Geoghegan, recalling the adventure with some pleasure.

The point was to learn about the difficult-to-sample viruses of aquatic mammals, including the humpback. Nineteen whale-blow samples were collected, leading to the discovery of six novel viruses from five families.

Three years later, Geoghegan faced another physically challenging task. No boats this time or giant marine mammals, but very late nights and full days tracking and tracing the nuances of SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Or as we’ve come to know it, Covid-19.

A senior lecturer in the department of microbiology and immunology at the University of Otago, Geoghegan is also an associate scientist at the crown-owned Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR). With colleagues like de Ligt, she helped build the case showing how the Covid virus is transmitted aerially and highlighted the importance of ventilation to minimise the risk of infection. At the very start of the pandemic, the scientists also pushed for government funding to allow genomic sequencing of the virus. As the virus continued to morph into new variants, the work ramped up accordingly.

“It was really hard work on everyone involved in the genomics lab. Everything was so time crucial,” says Geoghegan of that time. “You don’t really have time to think about getting fed up because you’re just doing it. It wasn’t till afterwards that you’re like, ‘Thank God that’s over’.”

Hundreds, if not thousands, of New Zealanders are still alive thanks to Geoghegan and colleagues tracking outbreaks of the Delta variant during the elimination phase of the pandemic. Some contemporaries believe she has helped save millions of lives around the world due to people avoiding the virus.

If the pandemic didn’t make Geoghegan a household name like “Dr Ashley” Bloomfield, Siouxie Wiles or Michael Baker, it may be her name’s Gaelic mix of consonants and vowels make a Kiwi tongue pause: it’s pronounced “gee-gan”. But her profile is high, not only among those who’ve been following the science stories of the pandemic but also among her science-community peers.

University of Auckland microbiologist Siouxsie Wiles says Geoghegan’s expert knowledge of coronavirus evolution was “exactly what we needed” when the pandemic hit.

“She immediately knew genomics could play a crucial role in our pandemic response and said as much every opportunity she could,” says Wiles. “She was right, and I’m grateful the policy-makers finally understood and listened. Her efforts, and those of everyone involved in the swabbing, PCR testing, contact tracing and genomic analysis have definitely saved lives and livelihoods.”

By August last year, that genome sequencing and wastewater testing had saved New Zealanders more than $3.5 billion in averted lockdowns, according to a New Zealand Institute of Economic Research report for ESR.

Geoghegan is a Rutherford Discovery Fellow, which, with a Marsden Fast Start grant, funds her research into why and how viruses jump to new hosts. At the end of May, it was announced that she had won the $200,000 Te Puiaki Kaipūtaiao Maea Prime Minister’s MacDiarmid Emerging Scientist Prize.

Talk to her peers, however, and they would say Geoghegan had already well and truly emerged.

Internationally recognised viral evolutionary biologist Eddie Holmes worked with Geoghegan when she joined his team on a fellowship at the University of Sydney. Holmes, who received the 2021 Australian Prime Minister’s Prize for Science for his work on Covid-19 and virus evolution, says New Zealand is lucky to have Geoghegan, a “scientist of rare ability”.

“She is one of the most brilliant problem-solvers I have ever met — nothing seems to stump her. She’s a bit like a Swiss Army knife when it comes to scientific research. This makes her an amazing collaborator, because you know she’ll be able to handle any problem.

“With Jemma and the rest of the team at ESR, it is really no surprise that New Zealand handled the pandemic so well. She’s truly a national asset.”

From her office on the seventh floor of Otago’s microbiology building, Geoghegan looks across to the historic clocktower at the heart of the university. The Water of Leith between them slices its way across campus to the sea, burbling gently down its rocky bed most days but roaring dramatically after heavy rain. Outside, a frigid sou’wester is blasting curtains of rain in front of the nearby hills and whistling through the university’s well-known wind tunnels.

On the deep windowsill on this side of the rain-spattered glass is a collection of her recent accolades, including her 2017 Australian Young Tall Poppy science award, a 2021 Otago University award for the best research paper of the year, and her PM’s science-prize trophy, which she hands over.

“Feel how heavy that is,” she says. It certainly is — a solid piece of aluminium cast in the shape of a Möbius Strip.

Geoghegan, 36, was born in the small Fifeshire, Scotland, town of Cupar. She and her three siblings had “a fairly normal upbringing” and went to the local high school. At school, a career in science did not immediately seem likely. Dancing was her first love. “I did ballet, and tap and jazz and highland. It was great discipline, and I recommend it for young people to have a physical activity that they are quite dedicated to. I was involved in the Scottish Ballet, so it was quite serious.

“I was very into dancing and thought, to be honest, I was going to go to dance school and not university. But at the later stages of high school, I got more excited about the prospect of going to university.”

She had discovered an interest in genetics and genomics. “I had a really great biology teacher. Teachers have such a big influence on the subjects kids like and go on to study.”

“She’s a bit like a Swiss Army knife when it comes to scientific research. This makes her an amazing collaborator, because you know she’ll be able to handle any problem.”

Before she enrolled at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Geoghegan hung up her dancing shoes and took a gap year. She was in Sri Lanka tutoring in English at a women’s vocational training centre when the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami hit. She stayed on to help with the immediate recovery before travelling to India and volunteering at an AIDS-HIV clinic in Pune.

Studying for her science degree in Glasgow, she specialised in forensic biology and the new frontier of genomic sequencing.“So it was kind of genetics but applying genetics into a forensic setting. And it wasn’t just human forensics, it included things like wildlife forensics and so on.

“Back then, genome sequencing wasn’t routinely done, it was very expensive and inaccessible. And the genetics revolution, genetic technology for sequencing, was only really just starting.”

After graduating early in 2009, Geoghegan wanted to study for a doctorate, but the global financial crisis had crimped the number of graduate positions in the United Kingdom.

“I thought going overseas would be a good adventure, and probably easier for me if I went to an English-speaking country. I’d always wanted to go to New Zealand — it was more of a whim than any well-thought out career planning. But it worked out well.”

Geoghegan answered an advertisement to undertake a PhD at Otago University with Professor Hamish Spencer, who had received a Marsden Fund grant to study gene expressions theoretically at the population level. Spencer says he chose Geoghegan for the post because of her “interesting” background.

“With a forensic undergraduate degree, she had problem-solving in her outlook right from the beginning. The project she did with me involved some mathematical modeling. She didn’t have a strong background there, but she had a real can-do attitude. She was keen to learn mathematical tools, and a lot of students are put off by that.”

Geoghegan credits her PhD with giving her a “really good fundamental background in evolutionary theory . . . and now I’m applying that to viruses”.

A postdoctoral fellowship followed at New York University. From there she went to the University of Sydney, before moving to a lectureship and leading her own research group — which led to the whale-snot gathering — at Sydney’s Macquarie University.

Geoghegan met her husband, Alex Latu, in her earliest days in Dunedin. It was his Fulbright scholarship for post-graduate law study that prompted the stint in New York. After their daughter, Zephy, was born in Sydney in February 2019, they returned to Otago: Geoghegan to her second stint with the university, this time in her joint role as an Otago academic and an ESR associate scientist, and Latu to a position in the law faculty.

In the labs of the microbiology block, Geoghegan’s work continues. She wants to better understand the diversity of viruses, the vast majority of which do not cause human diseases.

“We’ve probably discovered fewer than one per cent of the virosphere. Current knowledge is really biased on existing virus sampling, which is human viruses and viruses of plants and animals that are economically important. Whereas I want to actually discover viruses that might not be causing any disease.

“I’ve done a lot of fish-virus discovery work where we just sample seemingly completely healthy fish — ones that we would eat — and discovered viruses that are related to viruses we have — for example, the influenza virus and Ebola virus and coronavirus.

“We all just thought that they were for mammals and birds, right? We didn’t think they infected any other host type, but actually we find them in fish and reptiles and amphibians. So I’m trying to change the way we think about virus diversity. And actually, these viruses have been with us since vertebrates evolved. We were all fish about 500 million years ago.

“Humans and mammals tend to be pretty clean because we have an immune response to either get rid of the virus, or we die . . . But lots of reptiles, birds, fish and so on have a lot of different viruses just hanging out there and they don’t seem to be causing disease.”

Asking which species or virus is going to cause the next pandemic is the wrong question, she says. “It’s more about trying to understand how and why viruses jump to new hosts. We can only really do this by studying all viruses, not just the ones that cause disease.”

Science involves endless applications for funding. Geoghegan and her colleagues received $600,000 funding for genomic-sequencing equipment from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment in 2020 — after the Health Research Council turned down a joint Otago and ESR application.

“It took Hamish Spencer going in and being very persuasive, because he saw the benefit. He’s an evolutionary biologist, right, so he was like, ‘Of course we should fund this.’”

“The whole field is dominated by male colleagues. And they’ve been extremely supportive. But it’s hard to have a role model when you’re a woman, because you can look up to your male counterparts, but they’re not going through the same things that you have to go through”

Are we better off for having had that genomic testing? “Oh, 100 per cent. It’s played a starring role in this pandemic, not just in New Zealand but around the world. This project made sure that New Zealand was playing its part and we’ve had world-leading examples of research done here based on those data.

“And it has helped the pandemic response with sequencing genomes of cases, especially during the elimination, where every case mattered. The decision-makers would wait until they had their genomics results to link the case to the border, and they would make decisions on lockdowns based on that. The genomics prevented multiple lockdowns, with huge economic savings.”

Genomics testing is still needed with more recent variants, although sequencing is now of a very small proportion of cases, for surveillance at the population level and to monitor the virus’s evolution.

“We need to know what variants are in the community and which ones are becoming more dominant, because that really changes the way that you manage the disease. In hospitals, we need to know if hospitalisations are rising and of what variants, as treatments only work against certain variants.”

Unfortunately, some hard decisions had to be made with the arrival of the more transmissible Omicron variants late last year.

“If you just think about public health, then sure, the virus is not good and eradicating it was the best option. But there are other things to think about — and the economy can also be public health in terms of people’s livelihoods.

“At some point or another we did have to open up, and New Zealand arguably did it at the best time because we have about 97 per cent of people vaccinated. There’s a balance that you have to achieve.”

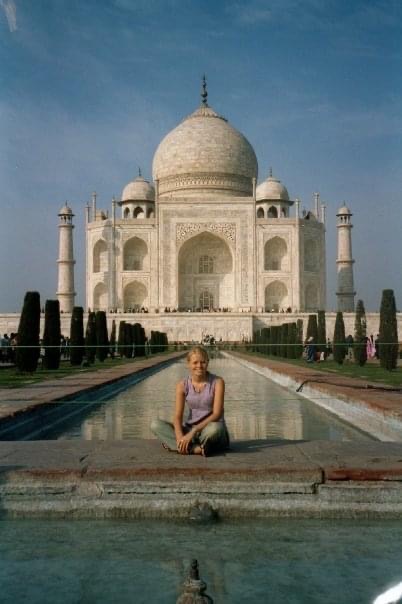

Geoghegan at the Taj Mahal during her gap year — a trip that also saw her in Sri Lanka when the Boxing Day tsunami struck.

“Launded scientist wants to inspire other women”, read the headline in the Otago Daily Times the day Geoghegan’s prime minister’s science prize was announced.

She told reporter John Lewis: “This award makes me feel like I’m contributing to breaking the stigma of what it means to be a person in science.”

The importance of having someone like Geoghegan in the vanguard of change is not lost on the prime minister’s chief science advisor, Dame Juliet Gerrard. She says the old adage that “you can’t be what you can’t see” remains a significant barrier to increasing the diversity of those studying science, technology, engineering and maths.

“So as well as informing the Covid-19 response and the public, Jemma’s media presence and growing public profile has undoubtedly inspired young women to pursue their interests in science.”

Geoghegan looks a little uncomfortable when asked about hurdles she has faced in such a male-dominated sector. “The whole field is dominated by male colleagues. And they’ve been extremely supportive. But it’s hard to have a role model when you’re a woman, because you can look up to your male counterparts, but they’re not going through the same things that you have to go through in terms of juggling having a family and just coping with everyday situations.

“That’s hard when I’m mentoring, because the vast majority of people in my research group are female students, and you kind of want to be someone that they can see themselves in as well.

“It’s very competitive, and I wouldn’t be where I am without other people opening doors for me. And it’s really been my mentors who got me where I am for sure. The vast majority of my mentors just happened to be men. But that’s not to say there aren’t amazing women out there and they’re very supportive.”

Parental-leave allocations can also make it much harder for woman academics in a competitive field to take time off and keep up with the latest research findings, she says.

Geoghegan wants to use her award money — which is hers to use in the pursuit of her speciality — to train more young scientists in virus ecology, evolution and emergence, to take pressure off the small genomics-testing group.

“It’s a really important field, clearly. But I think we do lack a lot of capability and capacity. During the first two years of the pandemic, and during community outbreaks, we were all working so hard all the time and there was no space for any breaks. We definitely couldn’t all take leave at the same time.”

Alongside the science Geoghegan excels in is another skill that has been vital in the pandemic — the ability to explain her work.

There is no doubt she is a science communicator par excellence, says Auckland University’s Wiles.

“I recently read a column by a well-known commentator who was proselytising to his large audience that scientists and other experts have no real value to society,” says Wiles. “Jemma’s contribution to New Zealand’s pandemic response shows just how wrong and dangerous that belief is. Her research and expertise have had significant real-world impact and she’s an inspiration to everyone who wants to make a difference in this world.”

Gerrard says Geoghegan has the gift of clarity of thought, which enables her to express huge amounts of complicated information in an accessible form for the public and policymakers.

And PhD supervisor Spencer is “immensely proud” of what she has achieved.

“One of the things I think is kind of reassuring is that Jemma is an example of a nice person doing well in science. You hear stories about really ambitious scientists who are complete bastards. And there can be complete bastards who are men or women. But one of the reasons it’s delightful to see her succeed is she’s actually a really nice person.”

ESR chief executive Peter Lennox agrees, and says the crown research institute is proud of its association with her and Otago University. “This is the way science should be done. We are blessed to have someone with her qualities, connecting with our other genome-sequencing scientists.”

ESR’s de Ligt knows Geoghegan as well as, if not better, than any other colleagues. He says the joint ESR-university appointment came about because he “didn’t want to let the opportunity slip by to work with one of the top viral genomics people on the planet”.

“All of this was happening before Covid and some people jokingly say we orchestrated the pandemic to show how important it was to do real-time viral genomics. In some ways, the timing was truly uncanny to have her on board while we were dealing with a global pandemic of this magnitude.”

Geoghegan is in full preparation mode for the imminent arrival of her second child and for taking six or seven months away from the lab. But she still has time to worry about where Covid-19 may go from here and how much we still don’t know about the virus.

“There’s going to be more variants and sub-variants, and we don’t know if they’re going to be more or less severe. We don’t know if our current vaccines are going to protect against them or not.

“We’re in a better place than we were in early 2020 obviously, because most people now have either got a vaccine or a past infection or both, to give them some immunity. But that’s not to say that a more severe variant couldn’t come along.

“The great thing is, we can put our faith in science to help us through this. We haven’t had such ultra-fast vaccine development and genomic surveillance in previous pandemics.

“In hindsight, I think we’ve done really well.”

Geoghegan and daughter Zephy with the prime minister’s science advisor, Dame Juliet Gerrard, when she received her recent Emerging Scientist award.

Paul Gorman is an award-winning science and environment journalist from Ōtautahi Christchurch.

This story appeared in the October 2022 issue of North & South.