Island Life

Over 35 years, a barren former sheep farm overrun with rodents has been turned into a lush landscape alive with native wildlife.

By Colin Miskelly

Mana Island. Photo: Tony Whitaker, Te Papa (CT.0067088)

The scene was apocalyptic. Fifteen million mice were eating their way through remnant populations of rare native species on Mana Island, two and a half kilometres off Wellington’s west coast. A report in the August 1989 edition of Time magazine declared that the 217-hectare island’s insects, birds and lizards didn’t stand a chance — they were being devoured by the plague of hungry rodents.

But this doomsday prediction never came to pass. I first set foot on Mana Island in 1992, two years after this ravenous horde of mice were eradicated for good, and I have returned more than 100 times since. On each visit over these three decades, the bird song has become a little louder, and the forest has grown a little more lush. Often overlooked or considered a poor cousin to the larger Kāpiti Island, 22 km to the north, Mana Island (which lies within the rohe of Ngāti Toa) is in fact the site of one of New Zealand’s most extraordinary conservation success stories.

The term “shifting baseline syndrome” is typically used in environmental circles to describe the incremental degradation of ecosystems. As both the size and number of fish in the ocean shrinks, each generation “forgets” what things were like when their parents were young, and recalibrates their expectations to match their own diminished experience. But baselines can shift in positive directions too.

Tony Whitaker. Photo: Marieke Lettink

Mana Island in the early 1970s was a barren former farm with a serious mouse problem. Tony Whitaker (above, with a New Caledonian gecko on his shoulder) took the top left photo in 1972. Fifty years later, natural history curator Colin Miskelly returned with his Te Papa colleague Maarten Holl to photograph the exact same landscapes (bellow) following decades of work by volunteers, Department of Conservation staff, and contractors.

Earlier this year, in late June, I made my way back to Mana Island once more, accompanied by Te Papa photographer Maarten Holl. We had a very specific purpose this time: to retake the photographs snapped exactly 50 years earlier (to the day — and even hour) by the ecologist and lizard expert Tony Whitaker. Along with two colleagues from the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Whitaker had arrived on Mana on 28 June 1972 to create an inventory of the plants, birds, lizards, insects and pest mammals found there. At the time, Mana Island was a crown-lease sheep farm run by the Gault family, who were still living in the island’s farm cottage (the cottage burnt down in the 1980s). Whitaker and his companions stayed in the island’s derelict woolshed for their two nights ashore. None had any inkling that decisions were already underway in nearby Wellington which would soon trigger a sequence of dramatic changes on the island.

Within a year of Whitaker’s visit, the government had bought back the island’s lease, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAF) established a quarantine research station for exotic sheep breeds on the island. In the days before artificial insemination, this was to be a major investment in improving the quality and productivity of New Zealand’s sheep flocks.

In 1990 the last mouse on Mana Island was caught, completing what was then the largest mouse eradication in the world.

Over the next five years, more than $2 million was invested on the island (about $26 million in today’s currency), including the construction of three houses, a new woolshed, a research laboratory, short-term accommodation, an implement and storage shed, two hay barns, a mating shed, a fuel store, two sewerage ponds, a generator shed with three diesel generators, and a wharf with overhead electric lighting. Five years later, the entire operation came to a shuddering halt when scrapie disease was confirmed in the flock in 1978.

The sheep equivalent of mad-cow disease, a scrapie outbreak would have been a disaster for the New Zealand economy if it made it off the island. MAF abandoned the island almost overnight, slaughtering the entire flock of 2000 sheep and burying them on site.

Strict quarantine controls remained in place for the next five years, after management of the island reverted to the Department of Lands and Survey. Restrictions were put in place limiting who and what animals could come on and off the island. Bulls were run there to keep the grass down to reduce the fire risk, while the department initiated a process to determine the future of the island.

In early 1986, the decision was made to manage the island for conservation purposes. Within months the bulls were removed, and work began removing the numerous fences. As the last barge-load of cattle left Mana Island that April, the departing farm manager is reported to have looked back at the island and bemoaned the “complete waste of a good island”.

This major change in management ideology occurred around the time that David Lange’s Labour government was making sweeping changes to the organisation and structure of government departments. The Department of Conservation was created in 1987 — the year before Mana was gazetted as a scientific reserve, with restoration of the island beginning in earnest.

McGregor’s skink. Mana Island. Photo: Tony Whitaker, Te Papa (CT.068190)

Goldstripe gecko. Mana Island. Photo: Tony Whitaker, Te Papa (CT.070027)

The 1972 discovery of McGregor’s skink and Goldstripe gecko were of great delight to Tony Whitaker, who noted the finding of seven McGregor’s skink with three exclamation marks (!!!) in his notebook.

Mana Island in 1987 was a very different place from the one-cottage sheep farm Whitaker photographed in 1972, but it still looked more or less like a farm — and it was still overrun with mice. Nevertheless, some very special wildlife species had managed to survive on the island. On his visits to the island Whitaker had made two astonishing lizard discoveries, including finding what we now call the goldstripe gecko, which was previously believed to live only in coastal Taranaki. On a previous trip to the tiny (and very steep) Sail Rock near Whangarei, Whitaker had discovered a species now called McGregor’s skink, 565 km to the north of Mana. An entry in his notebook for June 1972 (donated to Te Papa by his wife Vivienne after his death) recorded him finding seven “Sail Rock” skinks — with three exclamation marks!!!

Whitaker’s companion Mike Meads was equally surprised to find Cook Strait giant weta thriving on Mana Island during their 1972 survey. Five years later, Meads organised the first recorded translocation of a threatened insect in New Zealand (and possibly the world), successfully moving 43 weta to Maud Island in Pelorus Sound.

With the bulls gone and the grass growing rank — providing more food and cover — mouse numbers exploded. Conservationists became increasingly concerned that these special species would be eaten to local extinction.

In 1989, Colin Ryder was the deputy chair of the Wellington branch of Forest & Bird and a man of boundless energy and optimism. Inspired by the previous year’s attempt to eradicate rats from Breaksea Island in Fiordland, Ryder began lobbying the newly formed Department of Conservation (DoC) to attempt the same with the mice on Mana Island. Within months, he had secured the necessary support and funds, and the first application of poison bait on the island took place that July. Seven months later, the last mouse on Mana Island was caught, completing what was at the time the largest successful mouse eradication in the world.

Now, progress could be made on restoring native forest to the island. Mana had been grazed continuously for more than 150 years, so there was little forest left to either guide restoration or provide a seed source. The two DoC staff based on the island collected some seed from a remnant patch of forest that had persisted in a steep gully, but most was gathered from reserves on the adjacent mainland. The bulk of the germination was done offsite, with seedlings returned to the island to be cared for until they were big enough to be planted. Planting began in the sheltered valleys, before moving up the slopes to the plateau, with the effort peaking at close to 30,000 seedlings planted in a single year in 1996. Much of this nursery work and planting was undertaken by volunteers. Over two decades, thousands of school children, Forest & Bird members, tramping-club members and others visited the island, aiming to plant some 1000 trees and shrubs a day.

It took a few years for the planted trees to reveal themselves among the rank grass, but gradually the tawny slopes of Mana Island transformed to bright green, and patches of new forest merged and spread. By the end of the mass-planting period, close to half a million trees had been planted over a third of the island, creating a patchwork of forest, scrub and grass.

This decision not to plant the entire island was deliberate. In addition to keeping historical sites clear of trees, some of the special wildlife species on Mana Island — including giant weta and some lizards — require or prefer non-forested habitats. Since becoming a scientific reserve, Mana Island is also an important breeding site for another very special species that shuns forest, and which happens to be one of the world’s rarest birds.

Colin Ryder, pictured above in 2010, is remembered as a man of “boundless energy and optimism”. He was involved with Mana Island right up until his death in 2021. Photo: Mark Galatowitsch

Takahē were sensationally rediscovered in the Murchison Mountains near Te Anau in 1948, and for more than 70 years conservation managers have tried different ways to safeguard their tiny population, and to encourage the birds to breed and thrive. By moving a few birds to small islands the Takahē Recovery Group attempted to investigate whether the birds were true alpine specialists, or whether cold mountain valleys were simply their last refuge from introduced predators.

Takahē were first translocated to Mana Island in 1987, and the island has proved to be excellent habitat for them. It has held more than 40 birds at times — the largest population outside Fiordland. Today, about 20 takahe live on Mana, and they regularly produce more chicks per pair than other populations.

In conservation circles, Mana Island’s greatest claim to fame is that it is the site of the most complex and successful seabird translocation programme in the world. Burrow-nesting petrels (which include shearwaters and prions) are difficult to move, as they are strong fliers with excellent homing abilities. Some petrel species take up to 10 years to return to breed, and so it can take many years before a project can be declared a success. Trials undertaken on Mana Island revealed that this homing instinct develops while the downy chicks are in the nest, so if they are moved between islands a week or two before they are ready to fly, their homing mechanism can be reset so that they think Mana Island is home. It sounds simple, but this required developing an artificial diet and delivery method, so that chicks could be cared for while they completed their feather growth (sardine smoothies anyone?), and a lot of patience.

Diving petrel chicks were translocated to Mana Island in 1997, followed by fairy prions five years later and fluttering shearwaters in 2006. It is these birds that draw me back to the island year after year, to monitor their return and population growth. All three species are now multiplying on the island, with at least 63 chicks reared in the most recent breeding season.

Over the years, other bird species have been introduced including kākāriki (yellow-crowned parakeets) from the Marlborough Sounds; and pōpokotea (whiteheads), toutouwai (robins) and korimako (bellbirds) from nearby Kāpiti Island. Tūī have found their own way to the island too, and these species are now the most abundant birds on the island — astonishing, given their total absence less than 20 years ago.

For those permitted to stay on Mana Island overnight, one of the thrills is hearing and seeing rowi (Okarito brown kiwi). These very rare kiwi are longextinct in the North Island, but still survive in critically low numbers in forest near Okarito on the West Coast. Introduced to Mana Island in 2012, rowi are thriving, and are often encountered at night near the accommodation and along the island’s tracks.

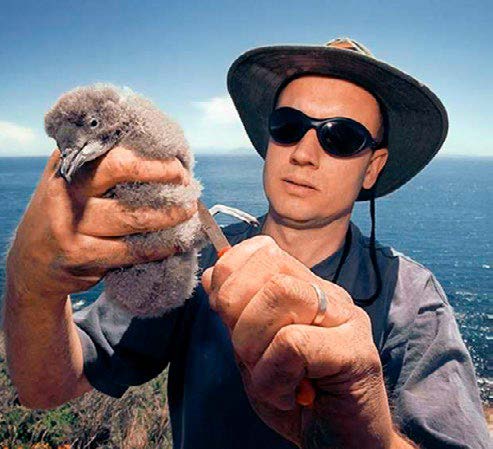

The author, above with a diving petrel chick on Mana. Photo: Dave Hansford

Conservation gains on Mana Island since the turn of the millenium have been achieved through a partnership between DoC, Ngāti Toa and Friends of Mana Island (FOMI), guided by the Mana Island Ecological Restoration Plan. Colin Ryder became the founding president of FOMI in 1998, and his passion for the island never waned. He was the FOMI guide for a group of day visitors when I last caught up with him at the island’s summit last year, only a month before he died.

FOMI have championed most of the higher-profile projects (including bird, lizard and insect translocations, research and monitoring, and developing recreational assets), raising the funds required and coordinating the bulk of the labour. Throughout this time, Ngāti Toa have largely been a silent partner, providing support and spiritual leadership at significant events, while responding to conservation initiatives rather than leading them. They had more substantive matters to focus on while preparing their Waitangi Tribunal claim. The Ngāti Toa Rangatira Claims Settlement Act 2014 granted a Statutory Acknowledgement and Deed of Recognition for the majority of Mana Island, in recognition of the status of Ngāti Toa as mana whenua. A requirement of the act is that the island will be returned to the iwi, and then be gifted back as Public Conservation Land, with 4.3 ha vested in Ngāti Toa Rangatira’s ownership. This includes the sites of Te Rangihaeata’s kainga, the toma (mausoleum) for his mother, Waitohi, and a taunga waka (canoe landing site). Once these transactions are completed, Ngāti Toa are expected to have a much greater role in the continuing restoration of Mana.

In the 50 years since Tony Whitaker first set foot on Mana Island, it has transformed from a barren sheep farm to a lush, tree-filled landscape bursting with a fantastic diversity of wildlife. Standing at the exact place at the exact time and on the precise day he took his photographs and seeing the results of so much thought, sweat and aroha was a powerful experience. Whitaker died in 2014 at the age of 69, but he would be delighted to know that the rare lizards and giant weta that he and his companions found are thriving, and the island is now dominated by regenerating forest and reintroduced bird species. The paired photographs taken half a century apart provide a new baseline for future generations to appreciate the kaitiakitanga of this very special island.

Restoring Mana from the bare paddocks of the above image was tricky. Retired pasture provided a vast area for weeds to establish — like the nasty and toxic boxthorn, which formed a dense spiny thicket around much of the shore and coastal slopes. Its removal required a team of contractors armed with power tools, goggles and leather gauntlets.

Mana Island, June 1972. Photo: Tony Whitaker, Te Papa

Mana Island, June 2022. Photo: Maarten Holl, Te Papa

Colin Miskelly has been actively involved with research and conservation on Mana Island since 1992. He is currently a natural history curator at Te Papa, and has previously worked for DoC.

This story appeared in the November 2022 issue of North & South.