Following The Threads

The loss of a collaboration between artist Colin McCahon and weaver Ilse von Randow has sparked both a deep search and a conversation about how we value art.

By Hayden Donnell

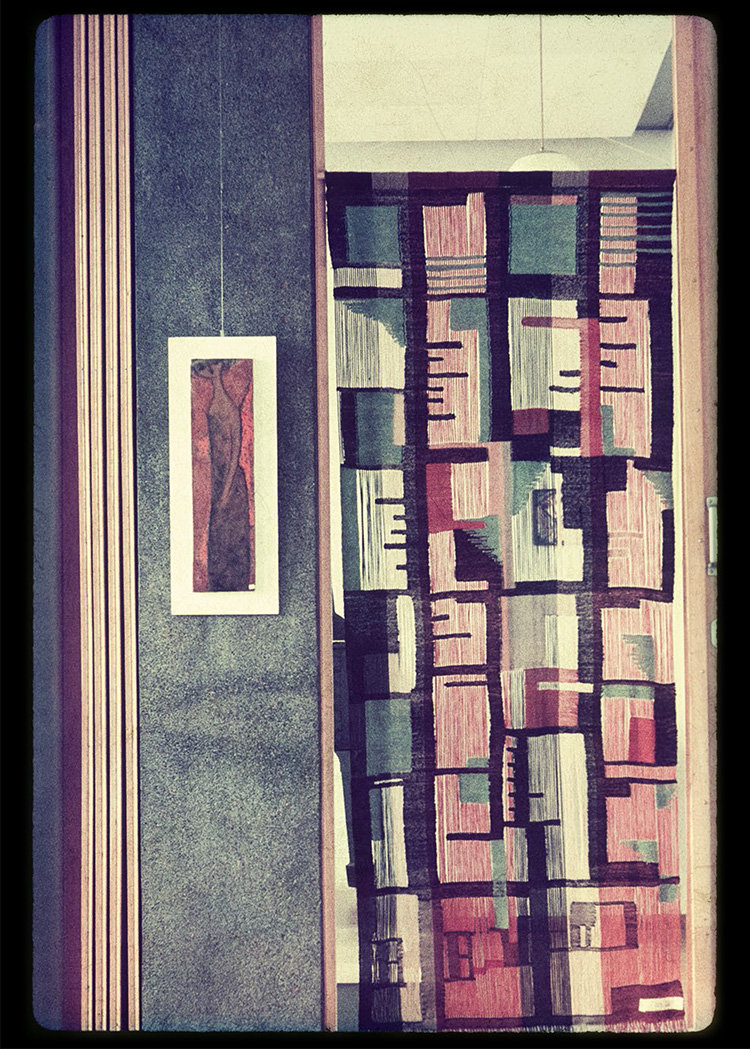

The only known image of Woven Kauri shows it hanging against glass at the entrance to the art gallery’s library. Photo: Kauri, Ilse von Randow and Colin McCahon, E H McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Douglas Lloyd-Jenkins, 2012.

Victoria Carr can’t remember much from when she was seven years old, but she can still picture the loom. It stood, solid and imposing, at the top of a spiralling staircase on the upper floor of Auckland Art Gallery. She would often clamber up those stairs with her father, the man many regard as the country’s greatest ever artist. While he would consult with the loom’s owner, a diminutive, dark-haired German woman Carr wasn’t interested. She just loved the loom. It reminded her of the stories she read about Sleeping Beauty and the spell-wreaking spindle.

Seventy years on, Carr now realises the slumbering princess was distracting her from one of the country’s most elusive pieces of art history. Her father, Colin McCahon, had just moved her family the length of the country for a job that didn’t exist. He arrived at Auckland Art Gallery thinking he would join its leadership team. There’d been a misunderstanding. Only a cleaning role was available, and he found himself mopping the tiles. The McCahons moved into a small bach in the west Auckland suburb of Titirangi. The space was barely big enough to house the family of six. The toilet was outdoors. McCahon had to work in the garage. But the new setting was an inspiration. Over the next seven years, he finished hundreds of paintings. Most of his major works are catalogued bar one: a weaving of a kauri that he collaborated on with the German artist Ilse von Randow in his early days in Auckland.

Their collaboration was called Woven Kauri, and it was likely created on the loom Carr remembers from the tower room of the gallery. The design historian Douglas Lloyd-Jenkins, who wrote his master’s thesis on von Randow, calls it “one of the most important missing artworks in the country”. At the time it was created, von Randow was in her 50s and McCahon his early 30s. They’d been brought together at the urging of the art gallery’s director Eric Westbrook, who commissioned them to work on something to hang in the building’s research library. Lloyd-Jenkins imagines the pair working into the night, with McCahon sitting beside the loom, drinking, talking, and, learning.

Von Randow’s loom, part of an exhibition of her work at the Auckland Museum in 1998. She gifted it to another textile artist when she left NZ in 1966 to live in London.

It’s unclear how much the process of making Woven Kauri influenced von Randow, who created the much-loved “Auckland City Art Gallery Curtains” (now part of the Auckland War Memorial Museum collection) and is remembered as one of the country’s best modernist weavers. Lloyd-Jenkins says it was one of the first wall hangings she made, and likely opened up artistic pathways which culminated in some of her most respected works in the 1960s. But he also remembers her as a person of sharply defined tastes, a deeply -committed modernist who took her own counsel. “I was very fond of Ilse and knew her in her last years. Not to disparage her at all, but she had her own ideas,” he says. Her grandson Daniel von Randow echoes that observation, saying she could be withering about artistic styles she didn’t respect.

McCahon may have been more malleable, and there’s evidence he found working on Woven Kauri a revelatory experience. It was the first of more than 50 works he would create depicting kauri. But the most profound inspiration he took may have been from how the work treated light.

Weaving involves threading two strands of yarn – a horizontal “weft” intertwined with a vertical “warp”. In Woven Kauri, von Randow left an unusual amount of warp exposed, with gaps visible between the threads. When the work was backlit, the effect would have been reminiscent of sunshine piercing a canopy of leaves. “She emulated what it looked like when a tree is in a forest and the light is coming through,” explains Coromandel-based weaver Kathryn Tsui.

Initially a science illustrator, Von Randow (at her loom above) designed textiles in Shanghai before emigrating to New Zealand. Photo: Archives New Zealand

Lloyd-Jenkins believes being able to see light passing through something he’d made opened McCahon’s eyes to a “new visual language”. When Carr looks at Woven Kauri, she sees a vision of her former home. She remembers walking to school along the kauri-lined roads that surrounded the family’s Titirangi cottage. “On a lovely morning, as I’d come up from out of the dark shade where the house is, the whole wall of kauri trees on the eastern side of French Bay Rd would be lit up with golden sunlight,” she says. “Great rays of golden light.”

If McCahon learned something from von Randow, it was likely a way to communicate the beauty of those Titirangi mornings; to show the essence of the moon shimmering as he fished by night in French Bay; to — in the words of Lloyd-Jenkins — weave light into the painted surface.

It’s hard to know for sure though, because Woven Kauri has been missing for 60 years. Auckland Art Gallery (now known as Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki) underwent refurbishment in the 1960s, with its works relocated to the Auckland Town Hall during construction. When it came time to rehang the art, McCahon and von Randow’s collaboration was gone. The only record of it now is a single grainy photo taken by von Randow. It shows the weaving hanging against the glass of the research library door, with another painting on the wall beside.

That could have been the end of the story. Though it has been the subject of scholarship by Lloyd-Jenkins, there was little effort to relocate Woven Kauri for decades, even as McCahon’s fame grew and his paintings sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars. That changed two years ago, thanks to an off-hand remark at a family lunch. Vivienne Stone is the director of McCahon House, a museum and gallery at the artist’s former Titirangi home. She was talking to her sister-in-law about her work when she heard something that took her by surprise. “She said, ‘and of course, he did that weaving with Ilse’.”

Stone had never heard of a collaboration between McCahon and von Randow. The comment sparked a two-year search for Woven Kauri, initiated by her, and driven forward by a collection of fellow McCahon and von Randow enthusiasts. They put up the picture of the work at the 2020 Auckland Art Fair alongside an essay by the researcher Sebastian Clarke. When that failed to produce any leads, they petitioned Auckland mayor Phil Goff to issue a search warrant for the work, and held a long-running exhibit at McCahon House named “The Search Party”.

The searchers have varying theories on where the work could be. Some believe it never moved, and is somewhere in the bowels of the art gallery. Others believe it could be hanging in the home of a former gallery worker or their family. The leading hypothesis though is that it got lost in the Town Hall during the renovation upheaval.

In the foyer of the Town Hall, Auckland Council’s art collection manager Peter Tilley is scrolling through a phone app containing details of every work on display in the building, from a sombre portrait of Captain Cook to a painting of the Duke of Edinburgh frowning down over the old Auckland City Council chambers. He’s at pains to prove Woven Kauri isn’t hidden in some forgotten corner of the council’s collection. Every work in its possession has been catalogued in stocktakes, including a major one in 2015 that cost $100,000. “We looked through every building that we can think of, every area we can think of, and we’re really thorough,” he says. Tilley refuses repeated requests from North & South to visit the storage areas where council keeps the art it doesn’t have on display. However he insists those works have been accounted for, and are just too poor quality, unfashionable, or plain ugly to put up in public. “Essentially the works we store are not worthy of display. But we know exactly what they are,” he says.

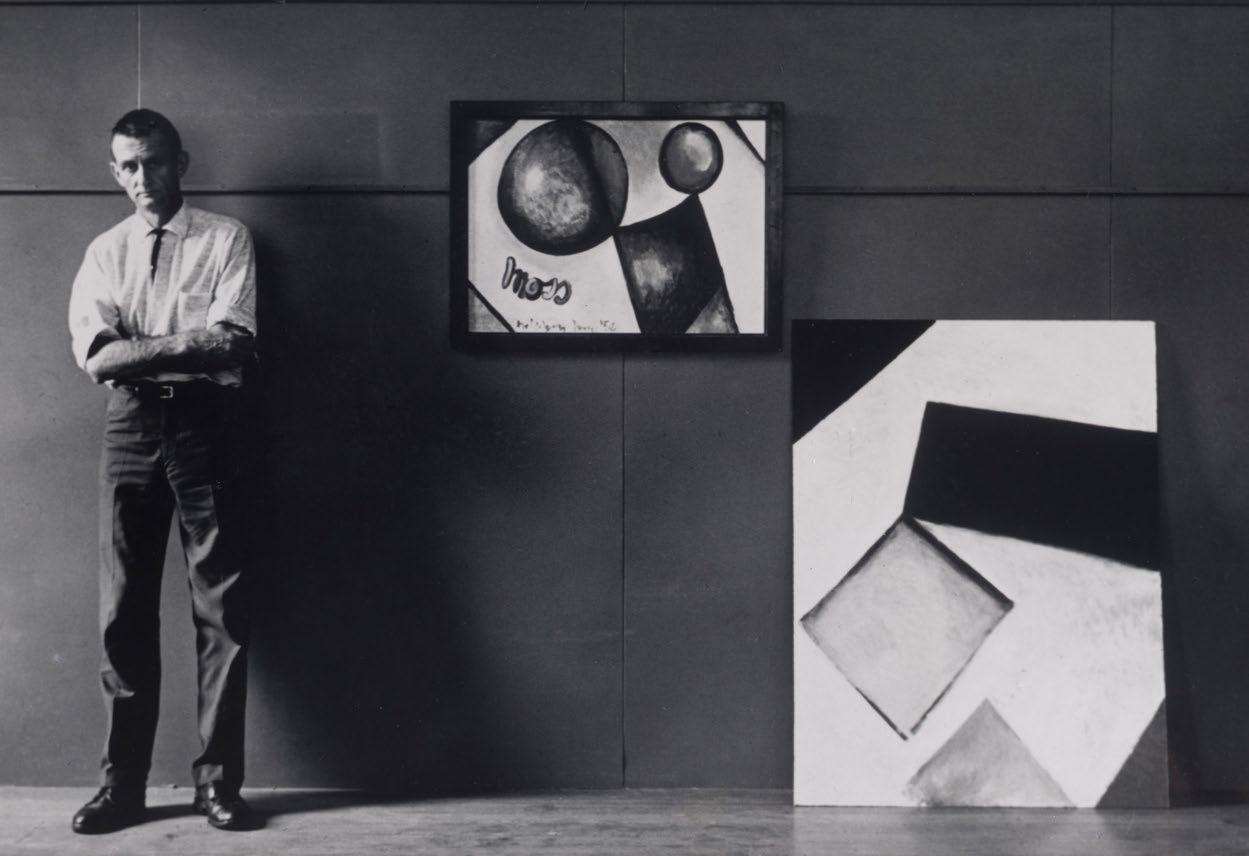

McCahon with Moss, 1956 and Gate, 1960. Photo taken by Bernie Hill, circa 1961. Photo: E H McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Tilley is backed by the staff at the council’s archives, who say they haven’t got any record matching Woven Kauri on file. Former council heritage advisor George Farrant is similarly pessimistic. He oversaw refurbishment work on the Town Hall from the 80s until his recent retirement. “In the 35 years or so that my close knowledge of the Town Hall and its contents encompasses, I have never encountered this memorable work, either on display or in storage,” he writes over email.

The Auckland Art Gallery is equally emphatic that it also doesn’t have Woven Kauri sitting in a box somewhere in a seldom-used basement. Its leadership team has been involved in the search for the work, and say they can’t have missed it sitting under their noses. A spokesperson for the gallery says its registrars are “certain” the work isn’t around. “In the last 20 years, they’ve moved the entire collection and have never found the item.” A paper stocktake of the gallery’s collection in the 70s also failed to locate the weaving.

That leaves the possibility that someone from the art gallery or the construction team either threw out the work or took it home. Stone imagines Woven Kauri still in use as a family heirloom, waiting for someone to recognise it as a significant piece of Aotearoa’s art history. “Our hope was that by shining some light onto this work that somebody would say ‘I know that I’ve seen that before at my grandmother’s house’.” Victoria Carr is less hopeful. “It could have ended up as a rag somewhere,” she says, chuckling ruefully. “People are like that. They’ll just throw it away without thinking. So many people don’t see value in something they don’t understand.”

“I just think she’s an artist who needed much more attention. It’s not enough to only have a grainy slide as the historical record of this beautiful collaboration.”

The possibility that Woven Kauri was pilfered or chucked in the bin only adds to the searchers’ nagging feeling that the work, and von Randow in particular, deserved better. Stone suspects sexism played a role in how little care was taken with the weaving. She’s certain though that its disappearance speaks to a hierarchy at play in the arts, where craft and design is often treated with less respect than so-called “high arts” such as painting and sculpture. “If it was a painting, it would have been well archived and documented. The fact that it could disappear so easily is a real reflection of what we valued at that time,” she says. Lloyd-Jenkins says the fact it’s even a possibility the weaving was taken home is testament to the second class status of the applied arts. “They didn’t say to people ‘take the art collection home’ during the renovation,” he says.

Bronwyn Lloyd, an art historian, was motivated to join the search after feeling offended on von Randow’s behalf. She says recovering Woven Kauri would rectify an injustice. “Out of respect for Ilse von Randow, I would love to see this missing piece found. I just think she’s an artist who needed much more attention. It’s not enough to only have a grainy slide as the historical record of this beautiful collaboration.” Daniel von Randow is certain his grandmother would have cherished seeing the work on display. “She would want it exhibited,” he says. “No question.”

Others aren’t so sure that would be the best outcome, or at least that it would be the only good one. At McCahon House, an array of 28 woven charms are arranged across a table. Each of them has a small slab of peacock ore stitched into its back, a substance which superstition holds as the stone for finding lost objects. Lloyd created one charm for each panel in Woven Kauri, and put them on sale in the exhibition “The Search Party.” Though she’s not a professional artist, her sense of loss over the weaving compelled a creative response.

In the room next door to where Lloyd’s charms are stored, McCahon once sat hunched over his desk as his children played in the small space by the fire. Kauri trees loomed overhead as he tinkered with light and shadow, filtering it onto a canvas in ways that recalled the weaving he once created with von Randow. Now thanks to Llloyd, his home is once again decorated with art inspired by that collaboration.

For Sebastian Clarke, who wrote the Art Fair essay on Woven Kauri at Vivienne Stone’s behest, that circle of creation may be the most satisfying legacy possible for the work. As we speak, a battle is raging in Auckland over the fate of its so-called “special character” suburbs. The city is sprawling over fields and wetlands, sabotaging itself in an effort to preserve the houses which speak of its past. Clarke sees some parallels in the way we try to preserve art, cloistering it away under white lights in galleries, and sometimes robbing it of its power in the process. He notes that if found, Woven Kauri would be consigned to a predictable fate. “We’d put it on the gallery wall for a limited time. We’d all say that it’s lovely. And then it goes away again,” he says.

Clarke sees something freeing in the weaving being missing, and beauty in the fact that it’s only preserved in a single unassuming, mysterious photo of it doing the job it was designed for. Even in its absence, artists like Tsui and Lloyd have been inspired to create their own work. People like Stone or Lloyd-Jenkins have used its story to fight for a reordering of our assumptions about artistic value. Even though it may be gone for good, disappearing into the mists of history, more collaborations, art, and stories are popping into being in the vacuum it left behind. “There’s nothing more I want to see from the story in some ways,” says Clarke. “I feel like that’s plenty.”

Hayden Donnell is a freelance writer living in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

This story appeared in the November 2022 issue of North & South.