Culture Etc.

Above: Train near Steam Punk Headquarter Museum.

Beyond Steampunk

In Aotearoa’s steampunk capital, a self-professed history geek appreciates a much more obscure connection.

By Thomas McLean

The distinctive limestone buildings of Oamaru, with their neoclassical forms and Corinthian columns, have long fascinated me. There’s something about the combination of grand European architecture, a sparse population, and the long, thin line of blue-and-turquoise sea that feels mysterious and melancholy. It’s like walking into a Giorgio de Chirico painting.

Oamaru’s ornate buildings sprang up in the 1870s and 1880s, proof of the seaside town’s importance as a storehouse and port for the wool and grain produced in the surrounding countryside. But the area preserves a much longer story of commerce: an exhibition at the recently renovated Waitaki Museum explores the region’s pre-colonial history, when Māori hunted moa, shipping meat to the mouth of the Waitaki River, where some 1200 umu (earth ovens) were put to use. The area’s later importance in New Zealand’s meat industry is evident just south of town at Totara Estate, which in 1882 used newly developed freezing technology to send the nation’s first shipment of frozen mutton to Britain.

As a history and architecture geek, I find this fascinating. But the moment I knew that Oamaru was my kind of magic lantern came on my first visit in 2006, at the Forrester Gallery. On the ground floor was an impressive exhibition of Colin McCahon works, recently donated by the artist’s family. Like Janet Frame and Douglas Lilburn, McCahon spent part of his youth in Oamaru, and the North Otago landscape informed many of his works. That was good, but something better was to come. On the wall at the top of the stairway was a remarkable painting of the ancient city of Petra by the Victorian artist and writer Edward Lear. This was an unexpected treat: there are beautiful Lear paintings in London, Cambridge, and New York; but Oamaru?

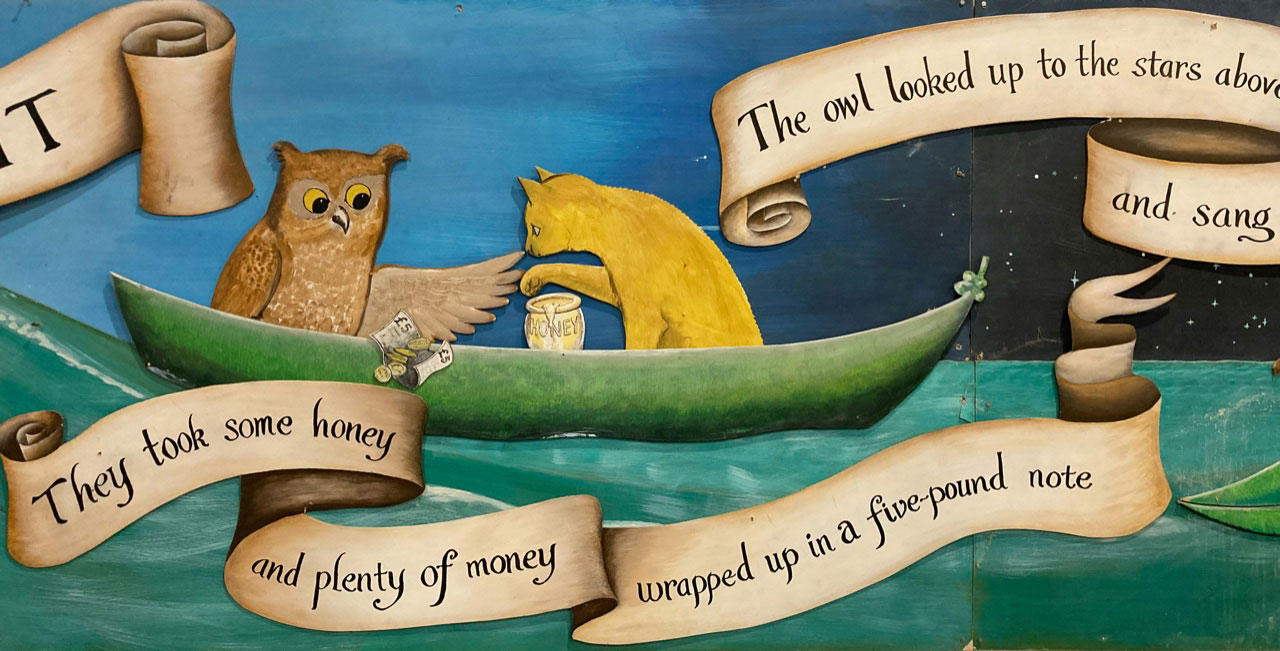

Lear is best known today for his limericks and nonsense poems like “The Owl and the Pussycat”, but he was he was an accomplished British artist and illustrator in the 19th century. (He was also, for a time, an art teacher to Queen Victoria.) He travelled widely, and in 1858 visited Petra, today in Jordan, the “rosered city half as old as time”, carved into a mountainside 2000 years ago.

Lear struggled with Britain’s art establishment, and he was often frustrated by the placement of his paintings high on the walls (making them difficult to examine) at London’s Royal Academy. When Petra was first exhibited there in 1872, it was overshadowed by its neighbour, a controversial new painting by James Whistler of his mother.

Lear never visited New Zealand, but his sister Sarah immigrated to Otago with her son in 1853. Lear was fascinated with Sarah’s new home; he even grew kaka beak on his Italian property, from seeds sent by his sister. After his death in 1888, Lear’s grandniece, Emily Gillies, inherited some of his belongings, and Petra seems to have been passed down among descendants. Only later did I learn that my encounter with the work was a farewell viewing: the painting was soon to be sold at Sotheby’s in London for — to quote “The Owl and the Pussycat” — “plenty of money”.

Few locals I’ve met have known about this fascinating connection between one of the quirkiest writers in the English language and one of the quirkiest towns in Australasia. Artist Donna Demente knows; and her charming mural in the Grainstore Gallery, created with Jeff Mitchell in 2002, brings to life Lear’s poem of the romantically entwined cat and bird who “went to sea in a beautiful pea-green boat”. The mural may be Oamaru’s only public reminder of the Lear connection; which is a pity, since Lear, who first gained fame for his extraordinary drawings of birds, whose poetry so often celebrated misfits, and who himself never quite felt at home in his era, might be a candidate for the patron saint of Oamaru (if not Aotearoa).

I’m a big fan of Steampunk HQ — I confess, I’ve waited patiently in a queue of eight-year-olds to take my turn at the Intergalactic Organ Pipes, then gone to the end of the line and waited again.

Step out of the Grainstore Gallery and take a good look at Oamaru’s Historic Precinct. Rescued from neglect in the 1990s, the area conserves some of the most memorable Victorian facades in New Zealand. But it isn’t a museum. Maurice Shadbolt wrote that Harbour St “has the character of an empty film set waiting for costumed actors to appear and a director to call for action”. The most interesting thing about the street is that, for all its Victorian elements, it can so easily become something else. In recent years, it’s played a Bougainvillean dream of Dickensian London (Mister Pip), 1920s Montana (The Power of the Dog), and the working-class neighbourhood of fairy-tale Lavania (The Royal Treatment).

It’s no wonder, then, that Oamaru is more neo-Victorian than Victorian. Donna Demente’s art may owe a debt to the Pre- Raphaelites, but she fuses those elements with an Antipodean carnival sensibility to create something new. The same could be said for Oamaru’s steampunk community. I’m a big fan of Steampunk HQ — I confess, I’ve waited patiently in a queue of eight-year-olds to take my turn at the Intergalactic Organ Pipes, then gone to the end of the line and waited again. But I don’t expect to learn much about the 19th century at such moments — they’re about the victory of imagination over history.

Wander a few feet beyond the Victorian Quarter and suddenly you’re on monumental Thames St. Blame the incongruity (or the wonder) on surveyor John Turnbull Thomson, who disliked the unhygienic aspects of crowded Victorian centres (fair enough) and designed a main street wide enough to turn a bullock team. The view of Thames St from the big windows of fab restaurant Cucina gives a sense of the grandeur. Remarkable buildings like the former Post Office, the Opera House, and the Forrester stand as testament to the era’s great expectations.

If those expectations faded a bit in the 20th century, they’ve come roaring back in the 21st, not least because of Oamaru’s thriving Tongan community, who, along with other Pasifika residents, make up about a fifth of the town’s population. In many cases, their parents and grandparents travelled to North Otago to play rugby or to work at the Gillies Foundry in South Hill; and now these Tongan New Zealanders are an integral part of the community. Earlier this year, Tongan Prime Minister Siaosi Sovaleni made an unexpected visit to thank them for their support after the 15 January volcanic eruption and tsunami.

As evening closes in, I grab the last pie from Harbour St Bakery and make my way to Friendly Bay to enjoy the view. After last year’s cancellation, the Victorian Fete returns in November, and there will be no better time to see Oamaru, old and new. Spend a few dollars at the Slightly Foxed bookstore, sample the beer at Scotts and Craftwork, and join the Owl and the Pussycat for a dance “by the light of the moon”.

Lear’s Owl and Pussycat, captured in a mural rowing their “beautiful peagreen boat” at Oamaru’s Grainstore Gallery. Photo by Thomas Mclean.

Thomas McLean teaches English at the University of Otago.

This story appeared in the November 2022 issue of North & South.