The Kirk Legacy

Norman Kirk was New Zealand’s 29th prime minister. A big man, his impact on Aotearoa remains significant after only two brief years in office.

By Ollie Neas

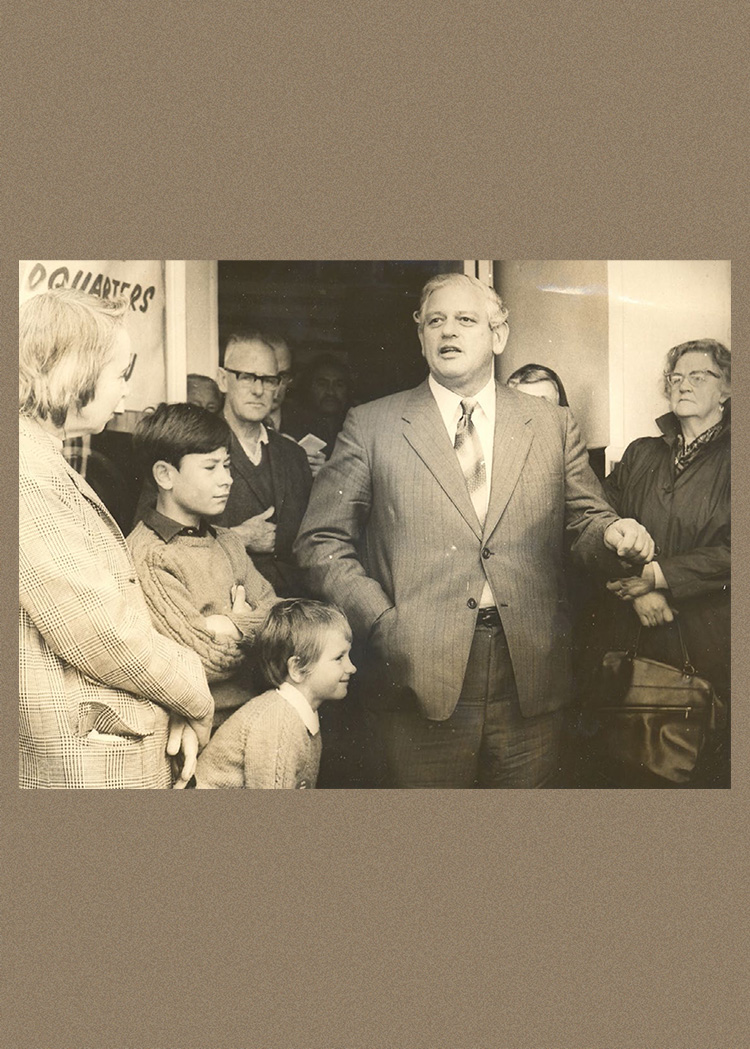

Opposite, Kirk in Levin, 1972. Photo courtesy of Horowhenua Historical Society Inc, Levin.

Fifty years ago this month, Norman Kirk was elected prime minister of New Zealand. Less than two years later, he was dead. His tenure was brief but his impact long-lasting, laying the foundations for New Zealand’s self-image as an independent and principled voice in world affairs. But the popular myth conceals the complexity of the man. The last working-class prime minister, he was also the first to be manufactured for the mass-media age. A principled humanitarian in world affairs, he was also a social conservative, as those who knew him recall, half a century on.

The bloke from Kaiapoi

Growing up up in Kaiapoi, Margaret Hayward paid little attention to the man next door. Mr Kirk, as she knew him, was just the father of her friends — Bob, Margaret and John.

The Kirks bought the empty lot next door when Hayward was seven. It was 1947 and building materials were in short supply. Without money to pay a builder, Norman Kirk decided to build a home himself, making all 1053 concrete blocks by hand. After work, he would cycle 20 kilometres to the Kaiapoi site from his job in Christchurch with materials strapped to his bike — composing speeches on the way of “all the things I’d like to tell the Tories”. When it was too dark to work anymore, he’d turn around and bike back. Eighteen months later, the Kirks had a home.

“My father, who wasn’t easily impressed, was quite impressed. I remember he thought he was one of the hardest workers he’d ever seen,” Hayward recalls.

A child of the depression, Kirk left school at the age of 12 after his father, a cabinet-maker, lost his job. As a teenager, he worked on the railways, mines and ferries. On night shifts, he read a book a night, and on smoko and meal breaks found himself drawn into political discussions, honing his arguments in debates with co-workers. By the time he moved to working-class Kaiapoi to take up a job at the Firestone tyre factory in Christchurch, he and his wife Ruth had the first three of their five children . He was 25 years old. Soon after arriving, he set about reviving the defunct local branch of the Labour Party.

One day in 1953, Kirk returned home to find a delegation waiting on his front steps, asking him to run for mayor. His parents tried to dissuade him — he had ideas above his station in life. But he ran and was elected, becoming the youngest mayor in the country at the age of 30 — at that time the youngest in New Zealand’s history. Four years later, national politics beckoned. Kirk was elected to Parliament as MP for Lyttelton.

But to Hayward, Kirk was just the man next door. Hayward’s father predicted Kirk would be prime minister one day. Hayward doubted it. A fat man would never be voted in, she said.

Years passed. Hayward left home, went abroad and returned, finding work in Wellington for British Insulated Callender’s Cables, the company that laid the Cook Strait cable. After bumping into Ruth Kirk at a wedding, Hayward received a call from Norman. It was 1967 and Kirk was now leader of the Labour Party. He had more work than he could cope with. Would Hayward consider working for him?

Hayward said no. “I really didn’t want to work for a politician. And I didn’t want to work for him simply because I knew Dad quite admired him. I thought, politicians have feet of clay. Do I really want to find out anything that Dad wouldn’t like?

“And then he asked me again. And again, I said no.”

Kirk persisted, calling Hayward at her office. One day, her boss answered the phone. He was astounded — why was one of the country’s most prominent political figures calling Margaret at work? “He’s been asking me to go and work for him,” Hayward explained. Her boss, who was about to return to England, insisted she take the job. “If he hadn’t urged me, I never would have taken it. So I did. And you know, I didn’t think he had feet of clay.”

Hayward began work in the leader of the opposition’s office, becoming the first female private secretary in Parliament for 25 years. A few years later, she was in the prime minister’s office, with an inside view of the Kirk government. Kirk asked her to take notes of everything, for memoirs he hoped to write one day. From the start, it was clear to Hayward that her concerns about working for Kirk the politician were unfounded.

“He was very thoughtful, and not just to me, but to everyone. He really felt for people. He was there because he wanted to make New Zealand better for people, but individual people he used to feel quite strongly about. He had very strong feelings, and felt strongly about people who had bad circumstances. And that’s really what drove him. I don’t think he had any real personal ambition other than to — I know it sounds trite — other than to improve things for ordinary people.

“I think that was what he was really all about. He’d had a tough time himself. He had a really hard childhood. And he didn’t have it easy when the children were small, earning a living and building a house. He knew that it could be very tough, even tougher for other people.”

Today, living in Ōtaki, Hayward’s days in Parliament are a long way behind her. After leaving Parliament in 1975, Hayward published Diary of the Kirk Years in 1981, before going on to study political leadership, a topic she continues to write about today. Decades on from the Kirk years, she saw reflections of the man in another young, newly elected prime minister, who happens to have a portrait of Kirk hanging on her office wall. “I’ve always had a smile when Jacinda came out with her kindness, when she said ‘be kind’, because I had always thought he was about the kindest person I’d ever met.”

Norman Kirk’s childhood home in the South Canterbury town of Waimate.

The Invention of Big Norm

It was February 1969, election year, and Bob Harvey, a fast-talking 28-year-old ad-man, entered Norman Kirk’s room at the Great Northern Hotel in Auckland to pitch the big man on an idea. “What the hell do you want?” Kirk said, sitting on the bed next to a suitcase. Harvey replied: “I’ve come to make you the prime minister of New Zealand.” Kirk roared with laughter.

Harvey had just returned from New York, where he had spent a week with Mary Wells, CEO of the leading ad agency Wells Rich Greene. One evening, Wells invited him to sit in on a meeting with members of the Nixon presidential campaign, to pitch them on an election campaign unlike anything Harvey had ever seen. “I’m sitting there with bloody huge ears listening. She’s talking about election themes — about the Vietnam War, about things that would make a political candidate or a presidential campaign exciting. It would be cutting edge with music.”

It was a revelation. Harvey realised he could do the same thing back home. And there was only one person he was going to approach. “I realised that I must, I must talk to Norman Kirk. That I had to talk with Norman.”

Three years earlier, Kirk had ousted Arnold Nordmeyer — a veteran of Walter Nash’s second Labour government in the 50s — as leader of the Labour Party, becoming the youngest leader of the party in its history. He represented a fresh start to a party which remained tainted by the memory of the “Black Budget” of 1958, when Nash’s government raised taxes on beer, tobacco, cars and petrol, costing it significant working-class support. But his image was anything but fresh. His suits fit poorly. His shirts were crumpled, his ties food-stained. But beneath the rough image, Harvey saw something special. “I saw him as the man who would take New Zealand into the next century, a man of extreme knowledge, of extreme ability to see where the world was going, and where we were going.”

Back from the US, Harvey asked a favour of Kirk’s communications advisor Gordon Dryden (later a prominent broadcaster). There, in Kirk’s hotel room, Harvey made his pitch.

Kirk roared with laughter. “Other bastards have tried. They’ve got nowhere. What the fuck do you think you could do to get me the job of prime minister?” Harvey recalls him saying. The ad-man persisted. “I want to design a new brand for Labour. A brand that’s contemporary, that young people vote for, and I think, Mr Kirk, they’ll vote for you.”

After a while, Kirk turned to his advisors. As Harvey remembers it, “He looked at the others. They said, ‘I think he’s got some good ideas going.’ And Norman then just said, ‘Well, give him the fucking business then. Sack those pricks in Wellington.’ I couldn’t believe it. “That was the beginning of my fantastic relationship with Norman.”

That weekend, Harvey got to work on what would come to be regarded as New Zealand’s first modern political campaign. First was the logo, replacing the fern leaf with a “running L”, designed by Dick Frizzell and Hamish Keith. Kirk’s crumpled shirts and shortback- and-sides hair-cut were swapped out for a more modern look. To use Kirk’s size to his advantage — he was more than 1.83m tall and weighed at one stage around 146kg — Harvey had photos taken of Kirk lifting weights, biking and jogging. Soft profiles about “Big Norm” began to appear in the weekend papers and women’s magazines.

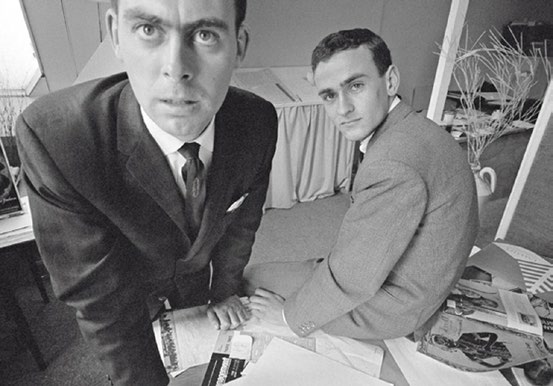

A man with a bold plan: Kirk-for-PM ad-man Bob Harvey, left, with Rex MacLeod, his partner in the agency they founded in 1962. Photo © Michael Gillies

At the centre of the campaign was New Zealand’s first split-screen advertisement, screened in cinemas and on television, which intercut footage of people surfing, kids smiling, young women in the street, and pensioners, with shots of the Vietnam War. Kirk didn’t appear until the end, with a clip of him walking up Parliament’s steps sped up to make it look like he was running. The Hamilton Country Bluegrass Band supplied the soundtrack: a pop-folk song titled “Make Things Happen, It’s Your Turn Now”.

Harvey unveiled his grand vision at the Labour Party conference. “They all burst into applause,” Harvey recalls. “And Norman looked at me and said, ‘Well, you’ve fucking done it now, haven’t you.’

Harvey unveiled his grand vision at the Labour Party conference. “They all burst into applause,” Harvey recalls. “And Norman looked at me and said, ‘Well, you’ve fucking done it now, haven’t you.’

“So Big Norm was launched for the election of 1969. And it was a triumph. At that moment, I created the cult of electioneering in this country. It would never change.”

It wasn’t enough. Labour lost the election in November. Keith Holyoake was elected prime minister for a fourth term. But there were positive signs — Labour had won four more seats, and was only one percentage point behind National in the popular vote. Were it not for an industrial dispute by ship workers in Auckland, Kirk believed they would have won.

And an unlikely friendship was born between the extroverted Harvey, whose advertising agency MacHarman Ayer went on to become one of New Zealand’s largest, and the down-to-earth Kirk. Harvey became part of Kirk’s inner circle, writing speeches and leading publicity — sometimes even ironing his shirts and polishing his shoes. Their relationship was often testy, with Kirk often frustrated by Harvey’s attempts to package him for public consumption. At least once, Kirk tried to fire Harvey, who was only saved by the party secretary refusing to carry out Kirk’s order.

In his last days, Kirk would tell Margaret Hayward that he had been tough on Harvey. As Hayward recorded in her diaries, “He’d been harder on Bob than he had been on anyone in his life, yet Bob hadn’t held it against him. He finds that wonderful, unbelievable in the context of political life.”

“Well, of course, he won,” says Harvey of the 1972 election which swept Kirk to power in a landslide. “The campaign was terrific. People loved it. We had banished National. And Kirk was this extraordinary, extraordinary, visionary leader who went from zero to hero in a week. They just couldn’t get enough of Norman. And to be honest, he couldn’t get enough of New Zealand.”

The Internationalist

As much as Harvey’s electioneering magic helped, the change Kirk promised at the 1972 election was about more than image alone.

Removing wage controls, limiting rent increases, expanding state housing, increasing health spending, taxing property speculation, ending compulsory military training, establishing a publicly owned shipping line, stopping the damning of Lake Manapouri, paying pensioners a Christmas bonus — these were just some of the policies set out in a 30,000-word election manifesto, known as the “Red Book”, which sold out around the country. Waving this book before them, Kirk instructed his newly elected ministers that implementing these promises was their priority, regardless of what the bureaucrats in the public sector advised.

The election had been fought largely over bread-and- butter issues. But for a younger generation of voters, who had grown up secure with the benefits of the welfare state, it was the government’s stance on foreign-policy issues that attracted interest.

Holyoake’s National government had, somewhat reluctantly, sent New Zealand combat troops to Vietnam in 1965. Kirk’s opposition to this was widely seen to have cost Labour votes at the 1966 election. But by the end of the 60s, as the appalling scale of Vietnam’s war casualties became clear and protests grew, Kirk’s stance was driving a surge in Labour Party membership, especially among younger, university-educated voters, whose support previously may have gone elsewhere. Among this new cohort was a young woman named Helen Clark.

Like many, former Prime Minister Helen Clark — pictured here aged 24, at the 1974 Young Labour conference — recalls exactly where she was when she learned of Kirk’s death. “I distinctly remember, it was Saturday night in Auckland when the news came through. No one was prepared for it.” Photo courtesy Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.

Clark joined the Labour Party as a student at the University of Auckland in 1971, galvanised by, in her words, “the Vietnam War, nuclear weapons, the anti-apartheid movement, those sorts of big things”. In election year, she found herself door-knocking for Labour’s candidate for the Waitematā electorate, Dr Michael Bassett. “People were ready for change,” Clark recalls. “The country had grown very tired of the National Government, and Kirk had built his reputation over the years.”

In 1973, Clark became leader of the party’s Youth Council. She would never meet Kirk in person, but he loomed large in the world she moved in. “For me as a young person, he was like a legendary figure in life and death. Huge personality, towering impact,” Clark says. “He was a great orator. He had a way with words. A man with very little formal education, but he could stand on a soapbox and command attention.”

Ties to Britain were loosening. The United Kingdom remained the largest destination for New Zealand exports, but its share was declining. Britain was on the cusp of joining the European Economic Community, threatening New Zealand’s access to the British market. It was no longer the “Mother Country”. To Kirk, this was an opportunity for New Zealand to redefine itself as a South Pacific nation with a vision and identity of its own.

Kirk doubled New Zealand’s international aid budget to the highest percentage of GDP for any New Zealand government before or since. Half of it was directed to the Pacific, much of the rest to Asia. Moved by the poverty he witnessed on a trip to Bangladesh, Kirk donated one per cent of his salary to charity. He officially recognised the People’s Republic of China and North Vietnam, opened new embassies in Moscow and Vienna, and expanded trade with Japan and South Korea. By the end of Kirk’s prime-ministership, trade with China and Korea had trebled.

Within a few months of taking office, Kirk had arranged to bring the troops home from Vietnam, sending humanitarian and economic aid instead. Compulsory military conscription was gone too, and those jailed for conscientiously resisting conscription released. New Zealand was no longer unquestioningly following its Western security partners. Instead, Kirk insisted, foreign policy was to be guided by a “moral” dimension.

In June 1973, after France refused to accept an injunction from the International Court of Justice to stop nuclear testing in the Pacific, Kirk dispatched the HMNZS Otago to Mururoa atoll, south-east of Tahiti, in protest. On board was a cabinet minister, Fraser Colman, whose name had been drawn from a hat. Kirk told the crew that their mission was to act as a “silent witness with the power to bring alive the conscience of the world”.

This “moral” stance attracted attention internationally. At the 1973 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Ottawa, Kirk earned praise and global media coverage for his negotiating style and forthright views on nuclear testing and apartheid. Shortly after, he made an impassioned speech at the United Nations General Assembly calling for nuclear disarmament and for the rich nations of the world to feed and educate the third world. Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew would later remark that Kirk was the most impressive prime minister he had ever known.

Tied to this vision of New Zealand internationally was an embrace of biculturalism domestically, with the government establishing the Waitangi Tribunal to examine current (but not past) breaches of the Treaty, commemorating the signing of the Treaty with a public holiday (then called New Zealand Day), increasing Māori representation in Parliament, and expanding Māori language education.

But in other areas, Kirk was out of step with the changing times. Socially conservative, he was strongly opposed to abortion and homosexual law reform (although, on the latter issue, he admitted to a friend in his final weeks that he could be open to “the other point of view”). Despite his turn to the Pacific in international affairs, Kirk’s government instituted the Dawn Raids on alleged overstayers, which terrorised Pacific communities. (Kirk discontinued the protests in the face of public backlash before they were later reintroduced by Muldoon.)

Kirk’s government was an overwhelmingly male one too —$there was just one woman in his cabinet, and only four in Labour’s caucus (National’s had none). At the 1974 Labour Party conference, Helen Clark joined a group of delegates on the conference steps to protest the lack of priority given to a speech by the Women’s Council President. Despite this, Clark sees Kirk’s policy agenda as socially progressive in most respects. “He wasn’t in tune with the modern sexual and reproductive health and rights debates at all. But apart from that, it was a progressive government without question.”

Clark points to the Domestic Purposes Benefit for single parents as a major achievement. “It was a very significant move, because you had the core social welfare from the 1938 Social Security Act$— the widows, children, the unemployed, the sick. But single parents had never been covered,” Clark says. “Women were under tremendous pressure to give up their babies and girls were often sent to homes for unmarried mothers, a lot of pregnancies were hidden from view.

“The Kirk government stuck by the fact that a woman with children on her own had to be supported . . . He was very committed to the welfare state.”

“I do remember the dramatic entrance he made at the Labour Party conference in May 1974,” Clark says. Recovering from surgery for varicose veins, Kirk defied medical advice to attend. “He made a speech and he didn’t look well. He had lost a lot of weight and seemed to be perspiring a lot as he spoke.” Something was wrong with the big man. It would be the last time Clark saw him.

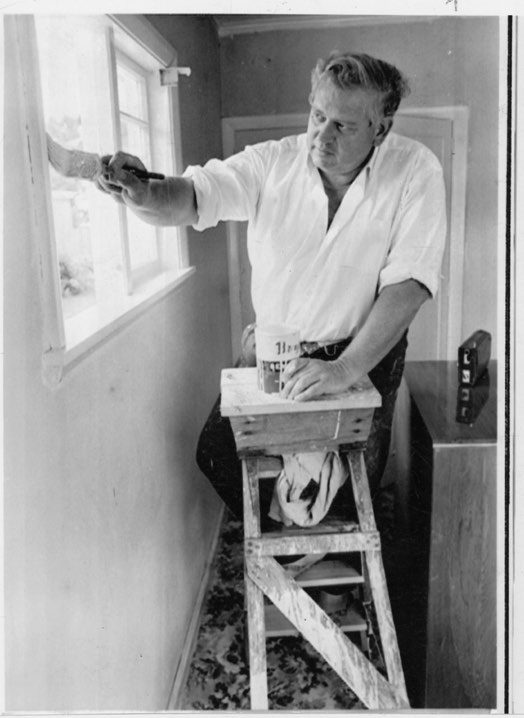

Leader of the Opposition and proud homeowner: the MP for Sydenham doing some maintenance at his Christchurch home in January 1971. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

A Death in Office

It was no secret that Kirk’s health was poor. But few knew how bad the situation really was. In April, he had surgery to remove varicose veins from both legs, and refused to rest properly afterwards, working from hospital before returning to Parliament the day he was discharged. The recovery did not go as expected. Kirk developed a blot clot in his lung, and became increasingly breathless, struggling to sleep. By August, it became clear even to Kirk that he needed a break. On 26 August, he started what was meant to be a six-week rest. Two days later, he was admitted to Our Lady’s Home of Compassion hospital in Island Bay. Three days after that, he told his wife he was dying. “Please don’t tell anyone,” he said.

Margaret Hayward had friends staying when she received the call from a colleague, Grey Nelson. “He rang me and said, ‘The prime minister has died.’ And I said, ‘Oh right.’ And he said, ‘You do realise what I’m saying, don’t you?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I do.’ The prime minister has died.

“So we just sat there and talked about it for the rest of the evening. And the next morning, I went early into the residence with Mrs Kirk, and I just took over the phones and did anything that needed doing the next day.

“Yes it was a shock. But if the job needs doing, it needs doing. So I felt very sad and very upset, but the next morning you had to be on the job again, because it had to be done.”

Tributes flowed in from around the world. Factories in Wellington ceased production. Buses stopped and shops closed. Within two days, 30,000 mourners had filed past Kirk’s coffin as it lay in state at Parliament. Across the road at St Paul’s Cathedral, Helen Clark was one of 800 invited to attend the funeral, while another 2000 stood outside in the rain, listening to the service on loudspeakers. “Crowds lined the streets in Wellington, lined the streets where the coffin went,” she recalls. “It was a very, very emotional time actually.”

When Bob Harvey learned of Kirk’s death, “I thought: ‘It’s all gone. It was an ad-man’s reaction, but I knew the whole thing was blown. Not poor Norman, but simply, we’re in the hands of Muldoon,’” he recounted to journalists a few years later.

Harvey’s instinct was right. Bill Rowling, Kirk’s replacement, lacked the charisma and vision of his predecessor. His prospects weren’t helped by an economic downturn, as commodity prices fell following the 1973 oil shock. The next year, Labour was humiliated at the election, as Muldoon stormed to a resounding victory. Labour crashed into the doldrums. It would be nine years before it returned to power, when it would use the opportunity to implement changes which — in the words of Kirk’s biographer David Grant”—”would have had Kirk rolling in his grave. The architect of these changes was one of Kirk’s young cabinet ministers, Roger Douglas.

By that stage, Helen Clark was herself in Parliament. In 1993, she became leader of the Labour Party and in 1999, prime minister. The president of the Labour Party she led was Waitakere mayor, Bob (now Sir Robert) Harvey.

The ghost of Kirk still haunted Harvey. He had never accepted the official explanation about Kirk’s death. In Harvey’s view, Kirk’s decline had been too sudden. He had made many enemies, and had always believed his phones were tapped. In 1999, ahead of an upcoming visit by President Clinton, Harvey called on Jenny Shipley to ask the US president to release the CIA files on Kirk, suggesting Kirk may have paid “the supreme price” for his opposition to nuclear weapons. A firestorm erupted. Helen Clark, leader of the opposition with an election around the corner, said it was outrageous — a position she sticks to today .

The position Clark inherited was shaped by Kirk’s legacy too. “Inspired by Kirk’s stand in Vietnam, the prospect of actually supporting an invasion of Iraq was just completely off,” Clark says.

“I look back and I see a guy who fought really hard for a government that had humanity and looking after people at its core and had a vision of an independent New Zealand foreign policy. There’s a lot of continuity from those kinds of values.”

Kirk was a larger than life figure. But despite it all, he did not believe in himself. In his dying days, Kirk turned to Hayward and said, “There’s not one thing I can look at after 15 years of being in Parliament that I can really point to as an improvement I made.

“Sometimes my suggestions have been taken over and implemented by others because they come within their portfolios. But what have I done to give New Zealanders a better life?”

To this day in Kaiapoi, the house that Norman Kirk built still stands.

Ollie Neas is a barrister and a contributing writer for North & South.

This story appeared in the December 2022 issue of North & South.