In Our Defence

Joining our army, navy or air force was once an assured way to build a career, gain marketable qualifications and save for a mortgage while living in subsidised housing. But with unfit houses and poor pay, the ranks are thinning dangerously — to the point where the most basic operations of a modern defence force are at risk.

By Pete McKenzie

Illustration by Ross Murray

The streets wind in great loops around empty lots. The grass is marked by the faded outlines of old boundaries, and trees have grown where houses once stood. To the south lies a graveyard, and to the east a youth centre that has been “temporarily closed” for years.

Once, this land housed thousands: the men and women who made Waiouru Military Camp hum, and the spouses and children who made it a home. Toward the end of the 20th century, 6000 people lived in the Royal New Zealand Army camp’s barracks or houses. They made Waiouru, in the barren middle of the North Island, the heart of the New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF). Today, however, fewer people want to live in its splendid isolation. Many of the army units that once used it moved to Palmerston North or Upper Hutt or Christchurch. By 2021, just 650 people were left.

That migration wasn’t limited to people. As Waiouru shrank, trucks carried away many of the homes that once populated the military housing area, leaving streets that lead nowhere and serve no one. Of the few shabby bungalows that remain, many are cold, draughty and in need of more than fresh paint.

Waiouru’s experience is symbolic of the NZDF’s wider decline. More than one in 10 military personnel have left the organisation in the past year. In an interview with North & South, Chief of Defence Force Air Marshal Kevin Short estimated that the attrition rate for the most skilled personnel was even greater: somewhere between 20 and 30 per cent. It is almost certainly higher now. “We can’t sustain that loss,” says Short. Then- Defence Minister Peeni Henare said last year, “These are some of the worst rates the NZDF has seen in its history.”

That has devastating consequences. The Royal New Zealand Navy has idled three of its nine ships for lack of people to crew them. A recent briefing to Henare explained that the NZDF was experiencing “significant fragility”. When asked whether the NZDF could maintain a peacekeeping operation in the South Pacific — the organisation’s most important task, after civil defence, in an era of deepening strategic competition — Short says it “would struggle”.

That is despite the government since 2017 ploughing $4.5 billion of additional money into the organisation: the military’s biggest funding boost in living memory. Practically all of it went towards purchasing new ships, better planes, and more reliable vehicles. Meanwhile, soldiers’ salaries stagnated and Defence housing wasted away. Now, the organisation’s personnel are heading for the exits. Can it be saved?

Waiouru’s central plateau location makes an ideal training ground. All images courtesy New Zealand Defence Force.

When Billy was five, he remembers sitting in front of the television and watching a muscle-bound action hero use a rifle as a haphazard flying fox to skid down a taut wire and kick a bad guy out of a watchtower. “Ever since then,” he says, “I’ve wanted to join the army.”

New Zealand’s army, however, has few open slots for action heroes. After a few years working on civvy street to get experience following high school, he enlisted in a technical role. (“Billy” is a pseudonym; he spoke on condition of anonymity.)

Military life was short on action-packed fights and long on health-and-safety approvals, but he enjoyed his work regardless. Then Covid-19 struck. Suddenly, he says, “You’re away for half a year doing Covid things and then when you get back everything is in disarray.”

Like 6200 other NZDF personnel, Billy was assigned to Operation Protect: the NZDF’s border protection mission. His job was to guard one of the rapidly established managed-isolation facilities at hotels in Auckland, Rotorua, and Christchurch. The banality of checking IDs and delivering UberEats was numbing. “It was so boring. You’re wasting your life,” he says. “You signed up to play sport, go overseas, go on training exercises, have fun. All the mean things the military is about were taken away by Covid.”

The experience fed his growing disillusionment. After three years of service, Billy was working for $56,000 a year; and his hopes of an overseas deployment seemed less and less realistic. By the time the military stopped guarding border facilities, he had decided to leave. His choice sparked a strange mix of emotions. “You have the relief of getting out and not constantly being in fear of forgetting your jungle hat,” he says. “But then also the sadness of never getting to go overseas.”

His experience is not unique. 77 per cent of military personnel are paid between five and 16 per cent less than people in equivalent civilian jobs. As a result, the number of people leaving has skyrocketed: by October last year, the NZDF’s military attrition rate was 15.8 per cent (ranging from 12.1 per cent for the navy, to 17.4 per cent for the army).

In a 2022 ministerial briefing, the NZDF’s chief people officer wrote, “Current attrition and an inability to fill positions are directly attributed to the distance of remuneration from the public-sector median. Fifty-four per cent of civilians and 38 per cent of military cite poor pay relativity as a key factor in leaving.” According to Short, “High attrition has left us with far less people than we expected. We’re pushing towards 1000 people less than we actually planned for.”

“If I got paid more, I’d probably stay,” says Billy. But “it’s hard to justify sticking around for a few trips when you could double your wages [as a civilian] in Australia and go on as many trips as you want.”

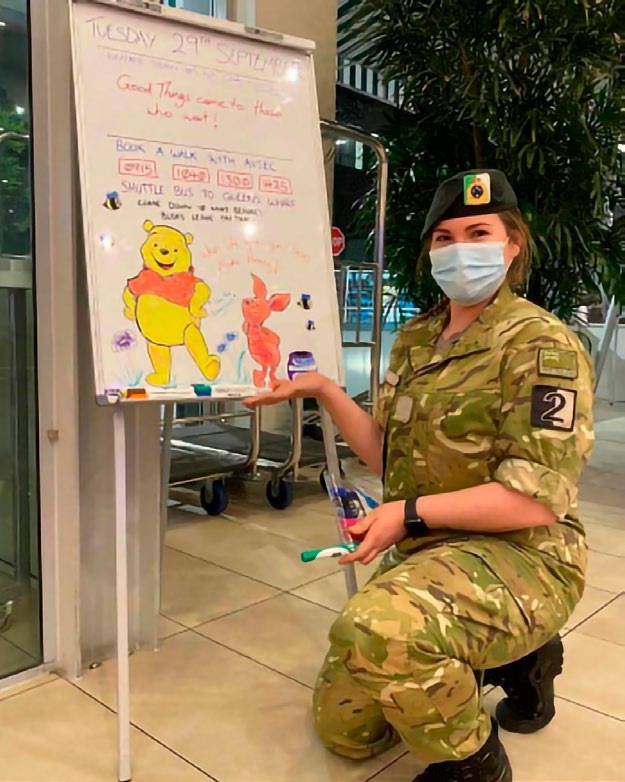

A soldier on duty at a managed isolation facility as part of Operation Protect.

The patch given to personnel involved includes references to health (the mānuka flower) and working together for a common goal (honeycomb).

Charlie has always loved the army. She joined soon after leaving school and was quickly sent overseas; she still thrills at the memory, years after the fact. Eventually, she left to raise a family. Even then, she knew she would eventually come back.

A few years ago, Charlie decided to do just that. (“Charlie” is also a pseudonym). The army posted her to a role in her speciality, but in a town far from where her family had been living. They would have to move, and the accommodation costs in their new location were far higher than what she had been paying.

The only way to make it work was to live in Defence housing, which is subsidised. By the time the paperwork was sorted, “it was just before Christmas,” she says. “The pressure was on.” With the help of a sympathetic housing administrator and a dose of luck, they snagged a multi-bedroom house just outside Charlie’s new camp.

At first, Charlie was stoked. “It does the trick for me and my kids: it has everything that I need. It’s a good, sturdy whare.” But partway through 2022, she says, “My rent went up about $200 a fortnight. That’s out the gate, really. It’s getting on par with normal rentals.” (As part of its tax obligations, the NZDF must review rents every three years). She doesn’t have much other choice:

“Everyone’s on the bones of their butt. Being in the army is getting to be a bit too much.”

if she lived further away, she wouldn’t be able to manage the competing demands of her children and her job. “I don’t have any other better option at the moment.”

In recognition of its employees’ sacrifices, the NZDF provides a range of other benefits: free dental care, a pension scheme, medical benefits. But the immediate challenge of paying rising rents on a limited salary makes them moot. Charlie has had to cut back on expenses elsewhere: food, after-school activities, trips to visit family. She wasn’t the only one to struggle. Some military families faced rent hikes of as much as 50 per cent in 2021; the average rent for a three-bedroom home went from $190 per week to $272.50.

Soon, even this option will be taken away from Charlie. Faced with enormous waiting lists, the NZDF limits people to six years in its houses. In a few years, she will hit that cap. “It’s a bit of a scary thing for me,” she says, “The six-year cap is stupid, especially in this day and age with the cost of renting.”

She’s unsure what she’ll do when that happens. If she hadn’t been able to access Defence housing in the first place, or if she had known to expect the steep rent increase, “I probably would have weighed up whether it was worth coming back.” As much as she loves it, she’s questioning whether to stay. “Everyone’s on the bones of their butt,” she says. “Being in the army is getting to be a bit too much.”

Not so cosy: houses at the Burnham Military Camp in Canterbury boarded up and considered not fit for purpose.

DON’T MENTION THE WAR

New Zealand is not alone in problems maintaining its military. As North & South publisher Konstantin Richter writes, there’s a Fawlty-esque element to the state of the services in his native Germany.

Some of Germany’s past defence ministers — they’ve come and gone in recent years — left for the oddest of reasons. Rudolf Scharping had to go because he and his girlfriend posed in togs for a glossy magazine while the army was getting ready for a risky peacekeeping mission. Another minister, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, quit because he was found guilty of plagiarising parts of his doctoral thesis. And then there’s Christine Lambrecht who resigned in January after posting a New Year message that was deemed inappropriate. (More on that later.)

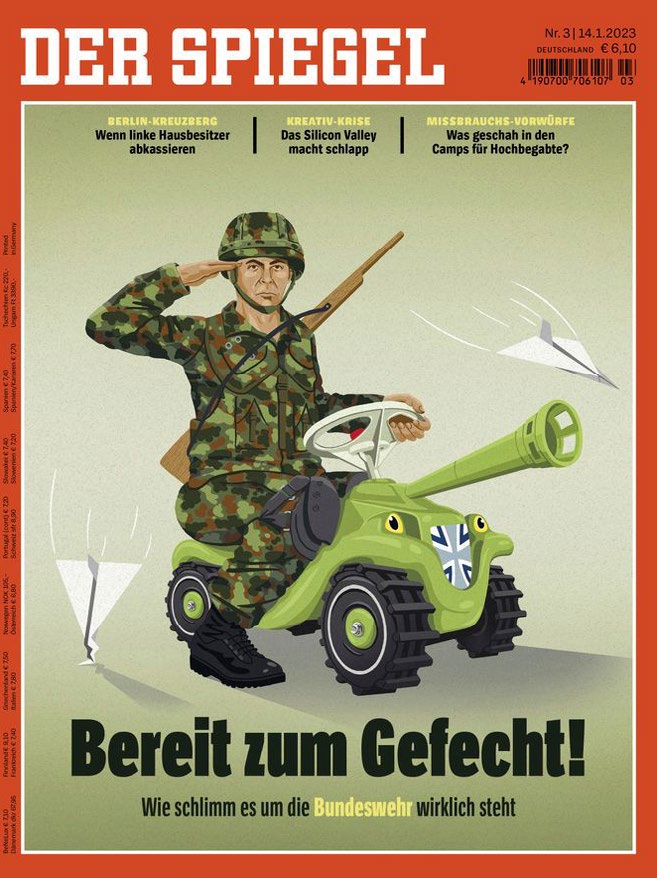

But no matter why they left, all of these commanders-in-chief had something in common: they struggled to address the enormous challenges that the German army has been facing — from a shortage of qualified staff to malfunctioning equipment to a missing sense of purpose. When Der Spiegel published a hard-hitting cover story about the Bundeswehr (which comprises Germany’s army, navy and airforce) earlier this year, the magazine showed a soldier sitting on a child’s car. “Ready for battle”, the headline read.

There are some parallels to the situation outlined in our story about the New Zealand Defence Force. But the need for immediate action is, arguably, even greater in Germany. The brutal battles raging nearby — Ukraine is 1500 kilometres away from the German border — may be the harbinger of a new Cold War, and Germany, located in the centre of Europe, would almost certainly be at the heart of it. Chancellor Olaf Scholz, a Social Democrat, said recently, in an article for Foreign Affairs, that the past experience of a divided nation gives Germans “a particular appreciation of the risks” associated with a renewed conflict between East and West. Even so, the Bundeswehr remains woefully unprepared.

To understand why the army of a nation that’s known for its efficiency doesn’t get its act together, it helps to look at the history. The Bundeswehr dates back to the 1950s when NATO needed more troops on the ground in post-war Europe. The Germans had to resort to conscription to build an army from scratch. In a conventional war, their forces would have been overrun by the Soviets in a matter of days. But they had nuclear support from the United States and they knew they were only there to deter, not to fight. So they moved tanks through the woods, preparing for battles that were highly unlikely to occur. Put simply, the Bundeswehr was never meant to function on its own.

Then, in 1989, the Berlin wall came down. There was a widespread sense that the era of geopolitical turmoil was over — and that kind of optimism was especially pronounced in Germany. Public opinion shifted against military expenditure. The Germans, who’d started two catastrophic world wars, had turned into passionate pacifists. Was an army even necessary? Who would want to work for it anyway? The Bundeswehr struggled to attract the kind of talent needed to manage the tricky transition to a post-Cold-War setting.

“Ready for battle”. In a recent cover story, Germany’s best-known weekly Der Spiegel explains how the nation’s army has turned into a laughing stock. Image courtesy Der Spiegel.

Successive defence ministers announced major reforms. Smaller, more nimble and less expensive — that was the general idea. No one was more energetic than the aforementioned Guttenberg, a popular Bavarian conservative who, at one point, seemed destined to follow Angela Merkel as chancellor. In an e!ort to leave his mark (and save billions of euros in defence spending) he ended mandatory conscription and downsized the military. The plagiarism scandal ended Guttenberg’s career but the damage was done.

Years of neglect and cost-cutting soon began to show. In 2014, shortly after Russia invaded Crimea, a German battalion participated in a NATO exercise in Norway. Having run out of weapons, the Germans used broomsticks instead of machine guns, attaching them to their tanks. Other embarrassing incidents followed. The ministry employed consultants KPMG to identify the biggest problems. A lack of leadership, the consultants said. They found that most Bundeswehr officials were extremely risk-averse and reluctant to take responsibility.

Russia’s invasion a year ago was a wake-up call. Chancellor Scholz came up with the term “Zeitenwende”, or turning point, meaning there would be more investment in defence and security. The government earmarked an extra €100 billion for the military. It’s almost certain, though, that all those billions will not be enough to meet the long-term target of 2 per cent of gross domestic product. In the meantime, the Ukraine war has, once again, exposed the Bundeswehr’s shortcomings. In a December exercise showcasing some of its most modern equipment, all 18 Puma tanks involved failed due to turret defects.

Social Democrat Lambrecht, the latest defence minister to quit the job, had a tough time from the very start. Public opinion was against her, possibly because she was a woman with no track record in military matters. Lambrecht said early on that she wouldn’t embark on another major Bundeswehr overhaul. Rather, she suggested, she’d make adjustments here and there — a statement that was interpreted as a lack of ambition. There were some blunders, too. A Bundeswehr helicopter, for example, used for a private flight with her son. (Lambrecht insisted that she paid for it.) Some criticisms may have been overblown. But most observers agreed that Lambrecht lacked the gravitas needed for what is currently the toughest job in German politics.

Then came New Year’s Eve. She posted a video on Instagram that showed her speaking in central Berlin against a backdrop of exploding fireworks. Looking back on 2022, she mentioned the war in Ukraine and said that, as a result, she had had “a lot of special experiences” and encounters with “wonderful and interesting people”. The new guy is called Boris Pistorius. He’s a former mayor of the smallish city of Osnabrück, and no one knows much about him. So expectations are low. But maybe that’s a good thing.

Charlie’s situation is better than many: her house is basic, but warm, healthy and spacious. That’s true of few other Defence homes. According to a 2020 analysis by consulting firm KPMG, of the 554 surveyed houses owned by the NZDF throughout the lower North Island (released to North & South under the Official Information Act), just seven were sufficiently warm and well-built to meet a core accommodation standard. Only 57 met the lowest legal standards for housing. More than 150 contained suspected asbestos.

It seems likely the report’s conclusions are representative of the roughly 1900 houses owned by the NZDF, and of the hundreds more barracks rooms in which many soldiers live. “When you think about the lack of insulation some [Defence buildings] have within the walls, and the age, and the way they’ve been built, they don’t meet modern living standards,” says Kevin Short, who characterised the state of Defence housing as “horrible”.

That has significant impacts for residents. In 2018, soldiers in Canterbury’s Burnham Military Camp were told to limit their showers to under two minutes because of an E. coli scare within the water infrastructure. In 2021, the NZDF informed the defence minister that up to 20 per cent of Defence houses might be built on soil contaminated with lead, arsenic, or asbestos.

Also in 2021, a mother of two in Linton Army Camp told Stuff that she worried their Defence home was causing asthma and eczema in her children. “Every year our children seem to get unwell with respiratory illnesses which I could nearly guarantee wouldn’t occur, or at least not as severely, if we had a warm, dry, healthy home.” Another military housing resident told Stuff her home was so bad she didn’t feel safe raising her 18-month-old child in it.

In a separate 2021 plan released under the Official Information Act, NZDF staff said they were “aware that houses in some locations are not in accordance with current guidelines and requirements for heating and insulation, and may pose health risks to service personnel and dependents”.

The NZDF has sold off hundreds of its buildings over recent decades without replacing them. As a result, for most personnel the only option is an increasingly unaffordable commercial market. “A lot of people feel that’s one of the perks of being in Defence: having cheaper housing, being able to save for a mortgage,” says Charlie. “Those dreams are going now.”

The brutal challenges better the NZDF now faces are the product of complex trade-offs forced upon recent governments and senior officials after decades of funding difficulties. My interview with Air Marshal Short, the NZDF’s chief, is in a spartan conference room at the NZDF’s newly constructed headquarters in Wellington. The Beehive and Parliament loom through a darkened window behind him. Short blames the NZDF’s challenges on inconsistent support from the government and says successive governments have had “too short a timeframe” on defence issues, focusing on wins they can score within three-year terms. “We need governments — no matter which [party] comes into power — to look at the NZDF and say, ‘We’ve got to look 10, 20, 30 years ahead’, and have consistent funding.”

According to the NZDF’s calculations, New Zealand’s defence spending as a percentage of GDP “swings between 0.8 and 1.1 [per cent],” says Short. “We can’t afford to do that, because that’s an over 20 per cent swing in funding that can happen over a reduced number of years, maybe just a couple of years.”

Instead, he urged the government to “set it at a particular point and sustain it”: choose a percentage of GDP — 1 per cent, 1.5 per cent, even 2 per cent (the latter is the amount called for by NATO, the trans- Atlantic security alliance with which we often partner) — and consistently fund the NZDF at that level. The alternative, he says, is “boom and bust” cycles that hobble our armed forces.

Politically, that inconsistency is understandable. Few civilians care about NZDF funding, and servicepeople can’t exert pressure they way others might. “When teachers want better pay, they go on strike and put children out waving placards and pulling heartstrings. Nurses, doctors, they all do the same,” says former Defence Minister Ron Mark, himself a former army captain. “Soldiers can’t go on strike.”

And yet for all that inconsistency, those soldiers have just been blessed with a boom: the $4.5 billion in additional funding the NZDF has received from this government is an investment of stunning scale.

Almost all of it went towards hardware, not housing or salaries: $2.3 billion on four new “submarine hunter” aircraft, $1.5 billion on five new transport planes, $100 million on 43 new armoured vehicles, and more. This is understandable. For a long time, the NZDF’s equipment has been falling apart. The Royal New Zealand Air Force’s planes were so run-down that there was a fair chance on any given international trip that the prime minister would have to hitch a ride with a friendly power. This happened most recently in October, when Jacinda Ardern had to fly back from Antarctica on an Italian military flight because the New Zealand plane that was meant to transport her had a broken propeller. In 2019, she flew home from Melbourne on a commercial flight when her RNZAF transport broke down.

“We need governments — no matter which [party] comes into power — to look at the NZDF and say, ‘We’ve got to look 10, 20, 30 years ahead’ and have consistent funding.”

“Aircraft were going to fall out of the sky, mate,” says Mark of the state of the NZDF at the time. Both National and Labour-led governments had “kicked the can down the road time and time again”, he says. “We were in trouble and something needed to be done.”

But as unfathomable sums of money were poured into hardware investments, the rest of the NZDF continued to wither. In a 2022 survey of NZDF personnel, a third said they were actively looking at leaving. Only 23 per cent felt they were paid fairly: a drop from 45 per cent the year before. Similarly, only 23 per cent said the housing or accommodation support they received was fair: a drop from 41 per cent. When asked about the asbestos and lead paint in Defence housing — as tangible a sign of the organisation’s crisis as anything — Short says, “Is that overall acceptable? No. But that’s the best we can do at the moment.”

The focus on hardware is partly a product of politics. In 2018, according to a Cabinet minute, Bill English’s National-led government directed the NZDF to “prioritise activities supporting the P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft and complementary capability infrastructure development” over fixing other parts of the Defence estate like housing.

That continued under the Labour-New Zealand First coalition: Mark — a New Zealand First MP — was Minister of Defence from 2017–20 and an enthusiastic advocate of equipment purchases. “In terms of capability and equipment, I was able to secure the biggest increase in 40, 50, 60 years. We’re seeing capabilities come online we’ve never had before,” he says. Despite his successes when it came to hardware, he claimed he was overruled when it came to pay increases. Anyone who criticises him for prioritising the former over the latter is “ignorant and doesn’t understand Defence at all”, he says. “I’d say that critic has never stuck his head up the tail of a C-130 and seen the degradation there.”

Of course, the focus on hardware was not solely a political decision. Especially in foreign affairs and defence, politicians rely heavily on advice from the civil service. The prioritisation of hardware was also partly the product of advice from the Ministry of Defence and NZDF senior brass.

Now we are entering the bust. Under pressure from the NZDF, the government recently contributed an additional $90 million over four years to help address salary pressures among military personnel. Short says he is pushing the government for another boost of “$60 million to give at least a 6 per cent to 8 per cent pay increase — not across the board, but where we need to address pay disparity.” But the government is under enormous financial stress; understandably, after its recent funding spike, defence has slipped down the agenda. The government has already deferred several major defence investments, such as a new Antarctic patrol ship.

When asked in a TVNZ Q&A interview whether he thought the NZDF paid military personnel enough, Defence Minister Henare said, “I don’t think we do. But we’ve made a contribution in this year’s budget towards remuneration.” Henare said he was working with other ministers “to see how we might be able to continue to help”. Yet when asked why the government hadn’t done more, he said, “Well, we’ve done quite a lot”. On 31 January Henare was replaced in the defence portfolio by Andrew Little in a cabinet reshuffle.

In 2019, in the government plan that spelled out how its enormous investment would be spent, Mark wrote that the decisions contained within it were “likely to shape the NZDF for the next 30 years or more.” He was right. Now the NZDF is struggling with the aftermath.

Chief of Defence Force Air Marshal Kevin Short at an event for Jayforce veterans at Government House, Wellington, in March 2021. Photo: New Zealand Government, Office of the Governor-General.

Former Army captain Ron Mark, pictured in 2018, served as defence minister in the first term of the Ardern government. Photo: US Embassy, CC.

These diffculties come at exactly the wrong time. The Pacific is gripped by the fiercest geostrategic competition in the region since the end of the Cold War and climate change is drastically worsening the natural disasters the NZDF is often called upon to respond to.

Midway through 2022, China signed a sweeping security pact with the Solomon Islands that would allow it to send military personnel to the island nation and potentially base naval vessels there. Collin Beck, the Solomon Islands’ permanent secretary of foreign affairs, later said the deal was necessary to address “domestic security threats”. Soon after, China proposed a similarly wide-ranging trade and security pact with almost a dozen other Pacific nations. It was an ambitious effort to win influence in the region that sent Australia, America and New Zealand scrambling.

“On anything related to security arrangements, we are very strongly of the view that we have within the Pacific the means and ability to respond to any security challenges that exist and New Zealand is willing to do that,” said Ardern, after news of the proposed Pacific deal broke. Eventually, Pacific nations rejected the deal, in part in reliance on such promises of Australian and New Zealand support. Manasseh Sogavare, the prime minister of the Solomon Islands, said he would only call on China if there was a “gap” in the assistance Australia — and, by extension, New Zealand — could provide.

But military attrition has jeopardised our promises. We lack sailors to sail our new ships, air crews to fly our modern planes, and soldiers to crew our sleek vehicles. Late last year, the NZDF recalled one of its patrol ships from the Pacific a month early and docked it indefinitely due to dropping crew numbers. It had already done the same with the other patrol ship that often monitors the Pacific. When asked whether the NZDF could sustain a hundreds-strong peacekeeping operation of the sort it conducted in the Solomon Islands in the early 2000s, Short says the NZDF “would struggle” to send more than a company (roughly 90 soldiers).

“Our ASEAN, South Pacific, Five Eyes partners are watching like hawks,” says Ron Mark. “Are we capable of patrolling the Southern Ocean? Probably not. Can we deploy a battle group? Probably not.” It’s a grim situation, he says. “I would say we’re in trouble with any major deployment.”

“There’s a concern, at the moment, with our region being more contested, that if you want security so that you can keep doing what you want — that doesn’t come free. There is a cost to that,” says Short. He says communicating that has been difficult. “It’s really hard to do when New Zealand’s been at peace for so long,” he says. “I don’t know how you get to that threshold through a government. They have to understand that. They have to engage internationally. They have to see that pressure.”

In the middle of the Waiouru training area, far from the camp or township, is the Moawhango Dam. I saw it last one morning in May last year when the sun had barely peeked over the Kaimanawa Range. As waves of gold-grey clouds washed across the sky, the dawn cast Waiouru’s hills in tawny bronze. A great trough runs east from the dam’s base into the mountains, and in the frigid air it filled with a lake of mist. The army chose Waiouru as its training ground a century ago in part because it is a hellish place to work. At turns freezing and roasting, it is lacerated by crevices and speckled with hills. But in moments like that morning in May, it is indescribably beautiful.

It is not just Waiouru’s beauty that attracts you, but its hardships. I experienced the briefest glimpse of that as an Army reservist: to laugh with your partner as you huddle in a gunpit on sentry, trying to keep your feet dry as rain sloshes down; to share boiled sweets with your teammates after patrolling for miles, your shirt painted to your back by sweat; to lie in a cosy sleeping bag while the night presses against your exposed face. Testing yourself, and working with others through difficulties, is satisfying. Waiouru is not the only place you can have these experiences: all people in the NZDF have some variation of them.

Some people join the NZDF for that beauty and that hardship. For others, it’s a stable job and a pathway to home ownership, among other aspirations. For the latter, the NZDF’s current difficulties are a dealbreaker. And even for the former, those attractions can’t sustain them across a lifetime. Meagre salaries and unhealthy homes make it hard to appreciate the NZDF’s rare privileges.

The result is an exodus of people, leaving the NZDF increasingly impotent. Who can blame them? Some, according to Short, have been offered salary increases of more than $20,000 by civilian employers. “They probably have mortgages and young families they’ve got to look after,” he says. “As we all know, the rate of inflation and the costs are escalating. And the easiest way for our people to look at that is to actually get really good jobs outside.”

Writer Pete McKenzie during his time as an Army reservist, refurbing kit following a field exercise in Waiorou. Image courtesy of the writer.

Pete McKenzie is a freelance journalist based in New York. He has previously served as a lieutenant in the New Zealand Army Reserve.

This story appeared in the March 2023 issue of North & South.