Culture Etc.

Julia Waite, curator of New Zealand Art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Photo: Florence Noble.

The Art of Exhibition

Julia Waite, Auckland Art Gallery’s curator of New Zealand art, talks about how exhibitions are conceived and presented.

By Gabi Lardies

The past few months have been eventful for Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Over summer it ran a blockbuster exhibition — 76,861 visitors came to see Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: Art and Life in Modern Mexico, causing the extension of the season — and Auckland’s new mayor felt moved to question the value of the gallery (amid misunderstandings over visitation numbers). Just as that verbal dust had settled, the end-of- January floods saw gallery staff bolt to the basements over a weekend to rescue works stored there.

From her desk in the gallery’s administration offices, curator of New Zealand art Julia Waite does not see a green glimpse of Albert Park, nor the glimmer of Guide Kaiārahi, Reuben Paterson’s glass and acrylic waka pitau installed over the forecourt pool. Books, catalogues, and files cover most surfaces in her office. On the wall are three small but important images. Two are postcards; one featuring a cubist painting by Picasso, and the other a woven kete. The third is a photograph of her mother on holiday in the Esk Valley in the 1950s.

Waite’s mother inherited a love of art and collecting it from her own parents, and so Waite grew up with art in her Wellington home. She remembers loving her grandparents’ Charles Tole painting of an industrial scene. “It’s perfectly poised between being recognisable and extremely abstract.” Waite was about seven when she decided she wanted to pursue art history. In due course, she studied at the University of Otago, in a department scrapped in 2020, despite student protests.

While studying, she worked at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, impressed by its extraordinary romantic collection. She could see there were many interesting roles in galleries and museums, but it was art she kept returning to. For six years, her focus has been on curating exhibitions that come to life in the floors of the building above her office.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera is gone and Light from Tate: 1700s to Now is now open as the gallery’s marquee attraction. In May, Brent Harris: The Other Side, will be the first major survey of the Melbourne-based New Zealand-born artist on our shores. It is timely, considering his recent work reflects a reconnection with Aotearoa.

You must be always planning what’s next. What are you working on at the moment?

I’m working on an exhibition about women artists’ contribution to the development of modern art in Aotearoa. It’s driven by an interest to challenge established understandings of modernism in New Zealand. That term, modern, still has currency and I want to bring greater definition to the history of the idea. What did it mean to be modern and to make modern art through the 20th century? Can we complicate those more established histories?

Where do the ideas for exhibitions at the gallery spring from?

The ideas primarily come from the team of curators who are following art practices in Aotearoa and offshore, visiting exhibitions, and conducting studio visits. Ideas spring from the artworks in our extraordinary collection, which comprises New Zealand and international art. You find yourself drawn to a particular work and can build an exhibition based off that one painting or photograph. We also have a rich archive in the E H McCormick Research Library to inspire fresh thinking about New Zealand art. Ideas grow through conversation, and we work as a team, advocating for the art that needs to be seen.

How does an idea for an exhibition turn into a list of objects?

It varies, depending on the scale of the exhibition. In terms of the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera exhibition, it took months to hone down the list of works, although it was never a question of reducing the number of Kahlo or Rivera paintings. Their artworks were the heart of the exhibition, and it was more a matter of refining the list of works by the other Mexican modernists to create a balanced exhibition. Of course there was this powerful couple at the centre of the Mexican art scene, but there were other equally strong artists whose work I wanted to profile.

On the other hand, I have curated an exhibition that consisted of only one work, Colin McCahon’s extraordinary multipart painting The Wake, 1958. That work, his largest, consists of 16 unframed canvases. On 10 McCahon transcribed the poem “The Wake “ by John Caselberg in his distinctive script and six feature land and kauri. It’s so powerful it could be shown on its own. We displayed the painting, which belongs to the University of Otago, in a small, curved gallery on the ground floor in 2019. It enveloped audiences and felt like walking into the forest of trees that surrounds McCahon’s house, which is still standing in Titirangi.

I imagine not all the works on a list make it into the final exhibition. Do you have a work which got away?

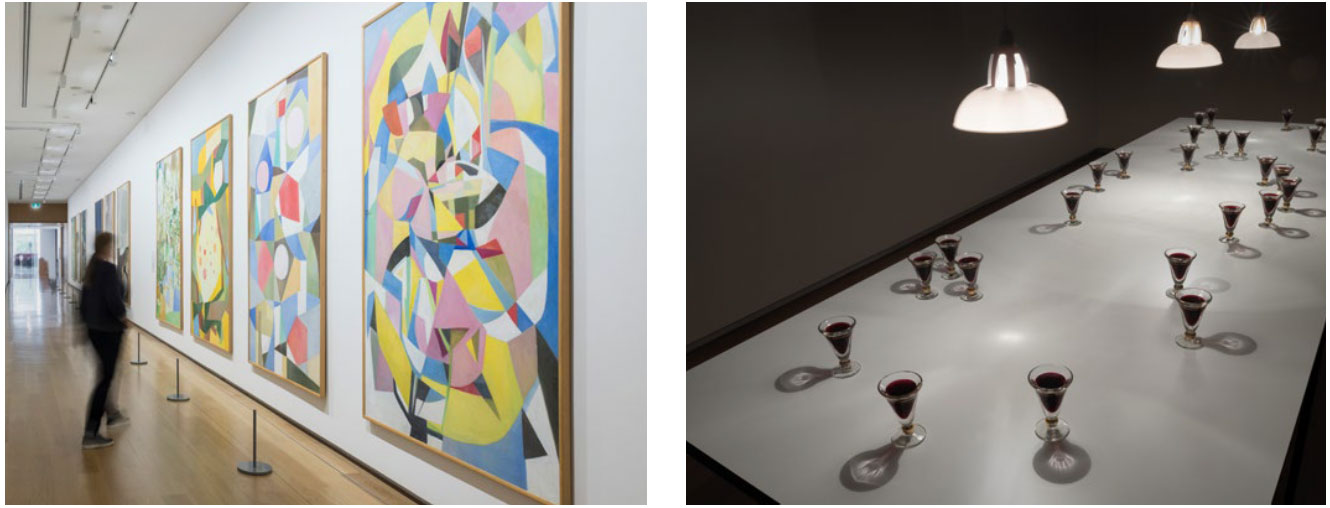

There are a few occasions that spring to mind. The recent exhibition Louise Henderson: From Life ended with her mighty The Twelve Months series of large abstract paintings, which she painted when she was 85. They are a tour de force and distil Henderson’s impressions of life in Aotearoa, recalling her Cubist roots and picturing the changing sights and moods of the seasons. I was sorry we could not include one of her winter months. August had been altered and was tucked away in a private collection — hopefully it can join the rest of the months one day.

Do you have similar feelings about works which missed being acquired for the collection?

Of course. There are major works which Auckland Art Gallery has missed out on acquiring over the years. The hope is that these pieces will eventually find their way into public collections so they can be enjoyed by the public for generations to come. But many more are acquired. When I look at a work like Michael Parekōwhai’s The Indefinite Article, 1990, I feel a huge sense of satisfaction that such a ground-breaking work is in a public collection. It will be protected and imbued with new meanings every time it gets shown in an exhibition.

Tell me about the journeys of artworks: How are they sent, packaged and cared for on their way to being shown?

I often borrow artworks from other public art collections in Aotearoa, or from private collectors, which takes a team of people to manage. Borrowing art involves insurance, assessing the condition of works, perhaps carrying out a conservation treatment, glazing and framing, building crates. The gallery has expert technicians who install the artworks in the space and the teams of conservators, photographers and registrars are also involved.

We recently installed contemporary artist Raukura Turei’s majestic canvas Te Poho o Hine-Moana, 2021. The painting is covered in swirling marks made from iron sand and the surface is extremely delicate so the sense of anticipation when it was installed was intense! The painting is hanging on the main sight line in the first space — I think it’s an extraordinary work to encounter when you first enter the gallery; it’s a work with strong physical pull and lyricism. It feels like it’s singing.

Left: Colin McCahon’s The Wake, 1958, marks a shift from structure to process and gesture after a trip to the United States. Right: Michael Parekōwhai created The Indefinite Article, 1990, from plywood and acrylic paint while studying at Elam.

The power of an exhibition is also in the relationship between works. At what point does layout and space come into play?

Space is fundamental to imagining the exhibition and to shaping it conceptually, and curators work with exhibition designers to ensure every element connects and reinforces the central ideas of the show. We work in close partnership to create a layered exhibition experience which visitors will respond to with their senses, emotions, and cognitively. The designers are incredibly skilled at interpreting the selection of artworks for a given exhibition along with the narratives or atmosphere the curator is trying to communicate.

The exhibition design needs to have life — a feeling of lift and energy. I’m looking forward to seeing the design of Light from Tate, which features a broad range of works, including painting, photography, sculpture, installation, drawing and moving image. Works like Olafur Eliasson’s crystalline sphere Stardust Particle, 2014, and James Turrell’s space-melting Raemar, Blue, 1969, require very particular conditions and I can’t wait to see them installed in our spaces.

Exhibitions are social spaces, so the designers are also thinking carefully about visitors’ comfort and making the galleries accessible to a range of people. Similarly, the interpretation, or wall text, needs to be clear, engaging, and free of art jargon — but that doesn’t mean it has to be simple.

How do you decide where to place objects? Do you have tools to visualise and try installations in miniature or digital worlds?

Yes, we have gifted exhibition designers who build the exhibitions with specialist computer software. All the spaces in the gallery have been modelled to scale in a virtual space along with the artworks. Having worked at the gallery for some years helps too, as the character of the spaces are familiar. In the virtual models, we can change the configuration of the walls, the wall colours, build plinths, and move artworks around with relative ease. We usually meet as a team for a virtual tour of an upcoming exhibition, and lot of eyes can see what works and what doesn’t. This is where we make final decisions on layout and plans for the installation technicians to follow. There’s also nothing like bringing the real works into the space and we adjust the design in real time when exhibitions are being installed too.

I’ve been told it’s best to walk into an exhibition room, scan it, and pick the two most alluring works to examine in depth. Does this approach make you shudder?

Not at all. Exhibitions are open spaces for visitors to experience art however they choose. When I travel to galleries overseas, I spend time with just a few artworks, rather than burden myself trying to see everything. Most of Auckland Art Gallery is free, and I encourage people to visit repeatedly as the exhibitions regularly change.

The hope is that people are fed by the range of exhibitions and that they develop their own relationships with works in the collection. There’s this tiny lead sculpture by Auckland artist Richard Gross on display now in the exhibition Manpower: Myths of Masculinity. It’s called Reclining boy and I adore it. It looks like you could have fished the figure out of a sardine tin — I wish I could have him on my desk at work.

You’ve curated exhibitions focusing on notable New Zealand artists, such as Bill Culbert, Louise Henderson, and Gordon Walters. What do you consider when putting together exhibitions from bodies of work by well-known artists?

Showing large bodies of unseen work is a major driver for me. The opportunity to see previously hidden phases of an artist’s practice can challenge preconceptions and shift how we understand their work. With the recent Bill Culbert exhibition, Slow Wonder, I showed Small Glass Pouring Light, 1982, which we borrowed from a public collection in France. It’s one of the most important pieces he made: an installation comprising a large white table covered in 24 glasses filled with red wine. Three shaded lights hang from above and cast light-bulbshaped shadows across the table’s surface. Most New Zealanders’ understanding of Culbert’s work was based on the installations he made here through the 1990s and 2000s, but I wanted to show more of the early ground-breaking work from his life in Europe.

In the case of Gordon Walters, his series of small and colourful gouache paintings made in Wellington in the early 1950s became a key to unlocking new understandings of his art. Our Walters exhibition profiled those experimental and riotous paintings and argued for their significance while shifting the emphasis away from the black-and-white koru-inspired paintings.

You’ve also curated exhibitions focused on movements, such as Cubism in New Zealand, and now women modernists. What drives you as you curate these?

I’m interested in revisionism and attending to those artists who have been neglected or under researched. The earlier generations of curators and art historians cut fascinating tracks through New Zealand art. They have left paths for us to continue working on, to deviate from, or challenge.

A love of art must surely guide you too. What’s your personal weakness in an artwork?

New Zealand photography is definitely a weakness and I like looking at collections online. I also like film noir, which probably informs my appetite for photographs. There’s an image by Dunedin photographer Gary Blackman called Motel bedspread, Taumarunui, 1981, which has got under my skin. It belongs to Te Papa and I want to see the real thing one day.

Left: The exhibition Louise Henderson: From Life culminated in her monumental series The Twelve Months, 1987. Right: Over wine, Bill Culbert saw glasses casting light bulb images. Small glass pouring light, 1983, documents the discovery. All photos courtesy of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Gabi Lardies is our junior writer funded by New Zealand On Air.

This story appeared in the April 2023 issue of North & South.