Flight Delayed

In 2019, at the peak of an unprecedented tourism boom, visitors were wearing out the country’s welcome mat. When New Zealand’s borders closed in March 2020, the government was faced with both an industry in freefall and a blank canvas for change. As international visitors return, has tourism really been reimagined?

By George Driver

I’d driven for five hours to visit Milford Sound, but when I arrived I couldn’t find a park. Prospective free spaces behind campervans disappeared like a mirage as hired hatchbacks were soon revealed in their lee. So on I drove. I had been warned. The previous evening, camping in the Eglinton Valley, a German tourist told me they had arrived at Milford Sound that afternoon and circled the parking lot for half an hour, waiting for someone to leave. In the end they gave up.

I was developing my own Plan B when, in the final row of the final bay of overflow parking, I sneaked into a space between a Winnebago and a Toyota Corolla, where a family sat inside eating their packed lunch in refuge from the sandflies. This was not like the postcards.

In the midst of a national park, in what has been called the eighth wonder of the world, I was soon facing another urban dilemma: Will the parking warden be working today? For experiencing the freedom of the great outdoors here is no longer free. It costs a minimum of $26 to park (which buys you five hours), along with a $1 transaction fee. With only a couple of pay stations in sight, I joined the back of a queue of about 15 people queuing to pay and waited, easy prey for the pestilent sandflies.

It was 10.30am on 3 January. The post-pandemic summer of tourism was underway.

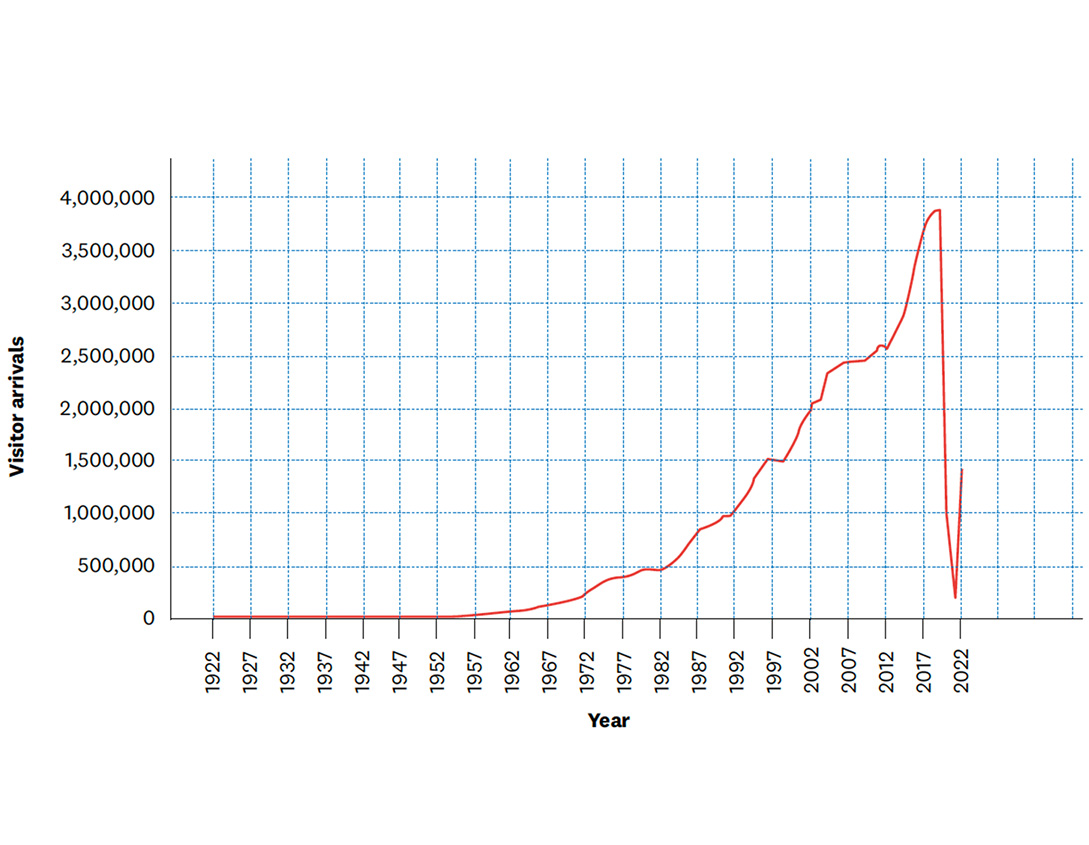

For those who visited Milford Sound just before the pandemic, this will be a familiar scene. In 2020, the number visiting Milford Sound was expected to reach one million, having more than doubled in the previous six years. The previous year, the number of tourists visiting New Zealand reached 3.9 million, almost a million-and-a-half more than in 2010. By 2024, visitor numbers were expected to hit 5 million, roughly matching the country’s population.

It had been an economic boon for some. Tourism became the country’s largest export sector, with international visitors spending and domestic tourists spending a further $23.7 billion. For others, however, this success was no cause for celebration. The term “over-tourism” entered the lexicon, and could be found in a growing number of stories about tourists’ track-side ablutions and selfie-queues forming on mountain tops.

These issues were seemingly solved overnight. At 11.59pm on 19 March 2020, New Zealand’s borders closed to non-citizens. About 70,000 people in the industry lost their jobs in the months that followed, many forced to leave the country as their work visas were rescinded. Others moved from crowd control to pest control under the government’s $1.2 billion Jobs for Nature programme.

But officialdom also saw opportunity in the crisis. In November 2020, newly appointed tourism minister Stuart Nash vowed that the kind of tourism that had defined the last decade would not be welcome anymore. “There is no going back to tourism circa 2019,” Nash said. A new term, “regenerative tourism”, became the phrase of the day. But three years on from the inauguration of the so-called hermit kingdom, has tourism really been reimagined in Aotearoa?

Crowded House

When Erna Spijkerbosch moved to Queenstown in 1970 she says the big event of the year was the Volunteer Fire Brigade ball, where she’d know everyone by name. That year, New Zealand attracted 167,293 visitors — about one tourist for every 17 of New Zealand’s then-population of 2.85 million. Queenstown wasn’t a tourism resort then, Erna says, just a small community of 1750 people. “I used to drive down to the mall in my van, double park in front of the only Four Square supermarket, go in and get my groceries and have a chat with the lady behind the counter. When I came out there would be no one waiting to get past me.”

In 1987, Erna and her husband Tonnie decided to sell their plumbing business and venture into the fledgling tourism industry. They opened Queenstown Holiday Park Creeksyde on the outskirts of town, on the site of an old plant nursery. By then, Queenstown was beginning to change. The world began to discover Aotearoa. That year, 809,256 international tourists came here, about one for every four New Zealanders — the country had grown to 3.35 million.

Slowly the campground grew too. Neighbouring sections were incorporated, and soon international visitors pitching up outnumbered the Kiwis. Erna became involved in the tourism association, Destination Queenstown, and served as its chair for a time. Queenstown began to be referred to not as a town, but as a “resort”.

By 2010, there were 2,516,683 tourists — more than one for every two New Zealanders. Then the industry really took off. On the eve of the pandemic, the number of tourists entering the country had reached 3,902,924, a 55 per cent increase over the decade. There was one tourist for every 1.3 New Zealanders. In Queenstown at peak times, tourists outnumbered locals 34-to-1.

“We no longer have the community we had,” Erna says. “Yes it’s progress and it’s a beautiful town and you can’t kill the mountains no matter how many tourists that you bring. But you can kill the enjoyment of living here.”

Selling New Zealand

The transformation was not by chance. In the 1990s, the government began marketing New Zealand with more gusto. Tourism New Zealand was formed in 1991 and it soon set a goal of trebling the number of tourists to three million by the turn of the century. The following year, one million tourists arrived in the country for the first time. The three million milestone was ultimately missed — there were just under two million tourists by 2000. But numbers grew sharply in the early 2000s, spurred by the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the launch of Tourism New Zealand’s “100% Pure New Zealand” marketing campaign to the world in 1999.

When arrival figures flatlined in the late 2000s due to a high exchange rate, oil prices and the global financial crisis (GFC), the government doubled down. In 2008, when the National government was elected, then-prime minister John Key appointed himself as tourism minister. The industry became a key plank in the economic recovery after the GFC. Funding for Tourism New Zealand leapt by 25 per cent, hitting $100 million in 2009–10 and reached $125.8 million by 2010–11. The agency’s budget had almost doubled in just seven years.

This record growth didn’t go unnoticed. In March 2020, the Tourism Industry Aotearoa’s (TIA) Mood of the Nation survey found that 54 per cent of people thought tourism was growing too fast, up from 30 per cent in 2016, and 42 per cent believed tourism put too much pressure on the country, up from 18 per cent in 2015. In Otago, that number reached 65 per cent and in Queenstown it hit 72 per cent.

It was easy to see why. On a trip to Queenstown in 2018, I felt like I was struggling against a sea of selfie sticks. I found similar scenes elsewhere in the country. On the Hooker Valley Track in Aoraki Mt Cook National Park I became an unwilling extra in a Korean video blog. In Wānaka, 30-minute queues were forming atop Roys Peak as visitors strove to get the perfect Instagram shot “alone in the mountains”. On the same social-media platform, there were more than 100,000 photos of a small crack willow growing in the shallows of Lake Wānaka.

These issues were summed up in a report by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE), former National MP Simon Upton, the following year. In “Pristine, Popular . . . Imperilled?” Upton said tourism “risks becoming an extractive industry”. He said overcrowding risked damaging the environment on which tourism depended, but the focus of the sector had largely been on growth, “with only superficial mention being made of community and environment”.

Upton found efforts to address issues with crowding had also mostly failed. While both the government and industry claimed to be focused on growing tourism spending, rather than visitor numbers, spending per tourist in real terms had remained flat for at least a decade. The spend per visitor was actually expected to fall in real terms. Upton also questioned whether attracting more high-value tourists would reduce the environmental impact of tourism. “Higher-value visitors, by definition, consume more goods and services, all of which have an associated greenhouse gas and solid waste footprint,” the report said. “Policies that support value-led growth are unlikely to reduce environmental pressures unless they are supported with policies that simultaneously aim to reduce the volume of visitors.”

Efforts to encourage people to travel during off-peak periods to lesser visited places had likewise failed. The proportions of tourist spending across the seasons, and between regions, had remained static. Upton asked why the government was ploughing more than a $100 million dollars a year into marketing tourism, when no other sector received such generous public funding for marketing.

People began to take tourism management into their own hands. On the eve of the pandemic, someone took a chainsaw to the Lake Wanaka tree, lopping off its photogenic lowermost limbs, leaving it lopsided. Aesthetically maimed, the tree survived but it would never be the same again, nor receive so many “likes” on Instagram.

In December last year, 55,096 people went on a cruise in Milford Sound, down from 94,818 in 2019, but numbers were rocketing back to pre-pandemic levels. Photo: George Driver.

A New Itinerary?

The crowds disappeared almost overnight when New Zealand’s borders closed. I visited Queenstown in May 2020, when bars and restaurants finally reopened after the Covid lockdown. I had no problem finding a park. It was like lockdown hadn’t lifted at all. Tourism businesses remained shuttered, the town centre was eerily quiet.

International tourists had made up 70 per cent of visitors to the town and the sector was at least 55 per cent of the local economy. Some places were even more dependent on international tourists. In Franz Josef, where 80 per cent of visitors had been from overseas, most hotels went into hibernation. By 2021, a quarter of the population left town and 60 per cent of jobs had gone.

Government support for the industry was swift. It rolled out a $400 million support package, including a $290 million “asset protection programme” to ensure major businesses could limp through the downturn. AJ Hackett Bungy controversially received $10.2 million to stay open (the Auditor General later found the criteria for the grants under the scheme was unclear and grants were given with limited evidence of hardship).

But the crisis was soon reframed as an opportunity. After the 2020 election, Stuart Nash was appointed tourism minister and declared the industry had been losing public support and the pandemic was “an opportunity to reset tourism in New Zealand”.

At the Tourism Industry Aotearoa’s (TIA) annual conference in November 2020, the minister revealed his priorities for the term. Top of the list was maintaining the country’s popularity. Nash said we must keep selling New Zealand to ensure it was considered in the top three places to visit “by the world’s most discerning travellers”. He later clarified that “discerning travellers” meant the rich. The minister declared the country would unashamedly target the super-wealthy tourist who “flies business class or premium economy, hires a helicopter, does a tour round Franz Josef and then eats at a high-end restaurant”, while two-minute-noodle- eating backpackers wouldn’t be encouraged.

Stuart Nash took over the tourism portfolio in the midst of the pandemic, but lost the role in a cabinet reshu!e in January to become minister of police. Photo supplied.

A tourism reset was the second priority, followed by introducing ways to ensure tourists contribute more to the costs of tourism infrastructure, rather than taxpayers and ratepayers. “New Zealanders should not be subsidising international visitors to the extent that we have done in the recent past,” he said.

The following year, Stuart Nash told RNZ that it was easier to regulate the tourism industry when it was going through adversity because “when things are going well it is very difficult to implement change”. “I’ve said numerous times that various former tourism minister’s filing cabinets are full of documents on how the tourism industry could and should change but nothing ever happens,” Nash told Checkpoint. “So now is the time to really drive home the change that I would like to see in this country.”

Three years on since the borders first closed, it’s still not clear how — or whether — the industry will transform. There have been a string of working groups and reports but few concrete policies.

Previous tourism minister Kelvin Davis established a “Tourism Futures Taskforce” in June 2020, consisting of representatives from industry, iwi and councils. It was told to develop ways to address tourism’s “longstanding productivity, inclusivity and sustainability (environmental, social and economic) issues”. Submissions to the group said the main challenge was “visitor volume” — there were too many tourists. However, its interim report, said the volume of tourists wasn’t a problem “within the limits of a genuinely regenerative visitor economy”. Its recommendations included developing new destination management plans, contestable government funding to encourage sustainability and more research and data on the industry, but nothing to address managing the volume of visitors.

A final report was due in April 2021, but the project was soon scuppered by then-Minister Stuart Nash (at the end of January, Peeni Henare was appointed to the tourism portfolio in a Cabinet reshuffle by new Prime Minister Chris Hipkins). Instead, Nash launched a Tourism Industry Transformation Plan, billed as “a partnership with the tourism industry, Māori, unions, workers and government to transform tourism in Aotearoa to a more regenerative model”. The first phase was developing a “Better Work Action Plan” for tourism and hospitality, with a draft plan released in August last year. Its recommendations include introducing voluntary standards for tourism jobs and developing ways to ensure employees can work or train during the offseason. Many of the recommendations, however, read like a word salad of bureaucratese. For example, the second recommendation proposes building “a programme of work that tells the stories of the application of intergenerational thinking, and the application of purpose-led business models”. The third recommendation is to utilise innovation and technology. A final report is expected imminently.

The second phase of the plan is focusing on the environmental impacts of tourism, however issues with noise and crowding are off limits. The plan’s scope states it “will not focus specifically on issues related to congestion or the loss of natural quiet which may be caused by tourism activity”. Again, the leadership group is mostly from the industry.

BOOK NOW

In 2021, a $3 million concept plan for the site was released which, if implemented, would probably be the most transformative tourism plan developed in a generation. It was developed by the Milford Opportunities Project, a group the government established in 2017 to make a plan to manage tourism at Milford Sound. It proposed limiting the number of people going their by requiring visitors to book a spot to go through the Homer Tunnel and for international tourists to pay a fee of up to $200 each. Revenue would fund infrastructure and conservation in Fiordland.

It also proposed banning cruise ships and campervans and closing the airport at Milford. Instead, most tourists would use an emissions-free hop-on-hop-o! bus service from Te Anau, allowing people to explore trails and huts along the way at their leisure. At Milford, a cable car and a new eco lodge could be built at the sound, and another at Knobs Flat on the road to Milford. Last year, the government gave the group a further $15 million to investigate if the plan was feasible.

Project chair Keith Turner says right now Milford is a mess. Most people visit on a one-day 12-hour-return bus trip from Queenstown, which means most visitors arrive at the same time. “The whole point of taking people in there was to show them something that they thought of as the eighth wonder in the world. And we simply were not delivering that. And the more people that turned up, the messier it’s got.”

While international tourists will pay, Turner says this will help transform the experience with new infrastructure and fund restoration work in Fiordland National Park. “If we can’t find $50 million a year to go into Fiordland National Park I’ll eat my hat. If you got rid of the rats and the vermin and predators and had the natural bird life that it used to accommodate, you’d have the first wonder of the world in my view. That’s a worthy prize and completely in character with New Zealand’s values.”

It’s been called a test case for management at other tourist-heavy sites like Aoraki Mt Cook, Fox and Franz Josef glaciers and Tongariro National Park. At the moment, charging and restricting access may not be possible under the Conservation Act so the proposal would require multiple law changes. The feasibility study is expected to be completed mid next year.

Departure Delayed

Efforts to develop sustainable funding for tourism infrastructure have also failed so far. In 2021, Nash had begun campaigning to increase the visitor levy. The levy was introduced in 2019, charging international visitors $35 to enter the country (Australian tourists were exempt). Before the pandemic it was expected to generate $80 million a year, with half of the proceeds funding tourism infrastructure and the other half going to the Department of Conservation.

Nash went to cabinet in August last year asking for the levy to be increased to up to $200, which would have brought in up to $444 million a year. A cabinet paper on the proposal said visitor infrastructure cost about $150 million a year, while DOC faced a further $96 million a year in tourism-related costs. A $200 fee would also dampen tourism numbers by six per cent, it said. However, cabinet voted against increasing the levy, instead telling Nash to develop a new proposal “in a collaborative way with the tourism industry” and come back next year.

The new minister, Henare, declined an interview request, saying it was too early to comment on whether there would be changes under his leadership.

However, in an interview with North & South prior to leaving the role, Nash departed from his earlier zeal for rapid reform. He said now was not the time to hike the visitor levy as the industry was still in recovery mode. “When we looked at it in the cold hard light of the post-Covid day, we made the decision that this is a very bruised industry and anything that is perceived as not helping the recovery, that this isn’t great timing to implement that.”

The government also wouldn’t do anything to limit the number of tourists coming to New Zealand, he said. “We need to rethink what tourism looks like in a post- Covid era — but not in terms of numbers, more in terms of delivery and value proposition and contribution to the community.”

Nash also walked back talk of targeting the business-class, helicopter-flying super rich. He said his comments about “high-value tourists” didn’t mean those with “high net worth”. “What I’m talking about is the aspirational middle, who come here, travel across seasons and regions, are environmentally conscious, buy into our values, respect local communities and cultures and appreciate the efforts and the worth of the local workforce. They learn about our history and culture, try new experiences, go off the beaten track and stay here a little longer.”

Backpackers, meanwhile, would be welcomed with open arms. “I’d love backpackers to come here because they work in our bars and restaurants and they pick our fruit and they tend to our vegetables and market gardens. But we’re not going to run a marketing campaign targeting backpackers.”

But then how will we attract these seasonally dispersed, environmentally and culturally conscious high spending, high value tourists? By marketing, Nash says. “What we’re attempting to do is to use our international marketing to spread the load. I would argue 50 per cent of all posters around the world advertising our wonderful country are views of Milford Sound, maybe Mount Cook. We need to go out to the world with a much stronger and more diverse value proposition.”

It doesn’t appear that Tourism New Zealand has got the message. Its social media still features “jaw-dropping views” of Milford Sound and Aoraki’s Hooker Valley Track that “needs to be seen (and heard) to be believed” — although lesser visited sites also feature.

It’s hard to see how this is a departure from business as usual, however. In 2016, John Key said the government’s tourism strategy was “to attract high-value visitors, not only to tourism hotspots during peak seasons, but to a range of regions, and throughout the year”. He said this was being achieved through Tourism New Zealand’s marketing “encouraging travellers to explore more regions, especially in the spring and autumn months”.

Going back further, in 2008 then-tourism minister Damien O’Connor said attracting value over volume was critical for the industry. “Tourism’s future depends upon sustainability and delivering greater value from each and every visitor to this country.” Later that year, O’Connor talked about the need for a tourism levy to help fund infrastructure and conservation.

Back in 2001 you could hear more of the same. When launching the government’s new tourism strategy, then tourism minister Mark Burton said two key principles of the next decade would be sustainability and that it “must increase visitor spend, rather than focusing solely on growing visitor numbers”.

Some changes are under way. In August, legislation was introduced to restrict freedom camping. The bill will require self-contained campervans to have a fixed toilet — previously a portable toilet sufficed and was often just a bucket of chemicals hidden away and seldomly used. There will also be a new registration system to ensure self-contained vans are truly self-contained. Non-self-contained vans will be banned from council reserves, but will still be able to stay at designated sites. It’s worth noting this has been in progress since at least 2018 and will still go through select committee and two further votes in Parliament.

Nash said the Tourism Industry Transformation Plan would also look at ways to fund tourism infrastructure in the third quarter of the year. “We’ve just delayed that until the rebuild is up and running and tourism businesses have once again found their feet. There may be other mechanisms, if not self-funded, then significantly contributing to the cost of tourism.” Although, a sceptic might say the government would be unlikely to propose any changes that could be framed as a new tax just before the election.

The government has also spent $47 million to help the country’s 31 regional tourism organisations develop plans to manage tourism in consultation with the community and a further $18 million has been spent to date on plans to regulate tourism in Milford Sound, but more on these later.

100% Pure?

James Higham says time’s running out. The University of Otago professor says that while there has been a lot of agreement that change is required and the industry needs to be guided by new values, this is yet to translate into actual policies. “The focus has been on jobs and the economy. It feels like the door is closing and the opportunity to reform the sector might pass.”

Higham’s research has focused on the greenhouse emissions from tourism. It’s not good.

It’s difficult to calculate the emissions from the industry — it’s not like a coal power station where the inputs are clearly defined. Tourism involves millions of people doing millions of different things with different impacts, but best estimates place the industry among our biggest polluters.

A Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment report estimated that tourism generates 12.5 million tonnes of greenhouse gas a year when accounting for both direct emissions (like driving a vehicle or flying) and indirect emissions (such as those from building a hotel). That’s almost equivalent to the emissions from all road transport (13.1 million tonnes in 2020) and about 16 per cent of our gross emissions. Stats NZ figures show direct emissions from the industry in 2019 equated to 6.9 per cent of gross emissions, slightly more than from New Zealand’s entire electricity network (5.9 per cent in 2020). About 60 per cent of the emissions were from domestic and international flights and 26 per cent from vehicles. The sector was also becoming increasingly carbon intensive. Between 2013 and 2019, the sector’s emissions had increased by 19 per cent, while its contribution to GDP grew at half that rate.

While vehicle emissions may reduce in future with more electric cars, Higham says aviation emissions will be much harder to address. Flying has become more efficient over time, but the growing number of passengers has meant aviation emissions increased by 25 per cent between 2010 and 2017. Air New Zealand plans to have zero emissions on their smallest regional flights by 2030, but there’s currently no low-emissions alternative for long-haul flights and Higham’s sceptical this will change in the foreseeable future.

The sector also gets a free ride in our climate change targets. Unlike almost all other sectors of the economy, emissions from international transport aren’t accounted for in our climate-change targets or greenhouse-gas inventory. This is because there is still no international agreement for how international aviation should be accounted for — should they be attributed to the country of origin or the destination, or shared?

The fuel used in international aviation is also exempt from our emissions trading scheme, effectively subsidising international flights. The Climate Change Commission will advise on how to account for international emissions by the end of 2024.

Higham says because of these impacts, going back to four million tourists a year is unsustainable without significant changes. One option is to introduce a tax on international flights, with higher charges for longer flights, and putting the money towards developing low-emissions aviation, as the PCE recommended in 2021. The fee could also encourage people to stay longer and therefore spend more, potentially reducing the emissions per dollar spent by tourists.

Tourism New Zealand could also exclusively target short-haul visitors and discourage those from destinations like Europe. We could also restrict large cruise ships, which are among the most carbon intensive forms of tourism.

But Stuart Nash says he isn’t interested in these kinds of changes. He says Australia already makes up the bulk of our tourists and North America and Europe are some of the biggest spenders. “I think that’s naive.”

Nash says international tourism can reduce emissions through biofuels, offsetting through forestry and electric vehicles. But without reducing the volume and the distance people fly, Higham’s sceptical. “The rebound of global aviation is happening very, very quickly. It’s hard to see how the tourism sector can be sustainable under these circumstances when we’ve got such enormous challenges that are unresolved.”

This graph, above, shows the speed at which New Zealand’s tourism population grew since the 1980s. Source: Stats NZ.

A New Flight Path

The industry, however, believes transformation is underway. Tourism Industry Aotearoa (TIA) Chief Executive Rebecca Ingram says we are “on the cusp of the next generation” of tourism. “I can confidently say the future of tourism will not look like the past because we’ve been forever changed by the last couple of years.”

Ingram says TIA is reviewing its tourism strategy so it’s focused on not just economic targets, but social, environmental and cultural ones too. The existing strategy has a target of increasing tourism spending to $50 billion by 2025. It was originally set at $41 billion in 2014, but that was increased once the target was almost met in 2018.

The association successfully lobbied against an increase to the tourism levy last year and Ingram says introducing a cap on tourism numbers or only marketing to short-haul destinations would be shortsighted. She points out that international flights also improve our connection to the world, enabling Kiwis to travel and to export our goods. “Tourism’s much more than just the visitors who come here. It has a halo effect.”

In smaller towns, tourism also means there are restaurants, cafes, and facilities that wouldn’t be there otherwise, not to mention the 229,566 jobs in the industry in 2019. And she says businesses have changed the way they operate, for example setting up pest control and tree planting programmes to help restore the environment.

New destination management plans that have been developed around the country will also change how tourism rebuilds, Ingram believes. The Queenstown and Wānaka plan, for example, includes a goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2030. The plan says it will aim for “optimal visitation levels,” and to attract tourist markets with lower carbon-intensities.

Destination Queenstown CEO Mat Woods says the plan won’t necessarily mean fewer tourists in Queenstown, but there will be scrutiny on the impact of tourists on different locations and activities. “It needs to be really granular,” Woods says. “If everyone is coming to do the same thing then clearly it would be too busy, but if people come to do different things — golf, skiing, biking, hiking — each of those has its optimal level.”

Some businesses are already choosing to accommodate fewer people. Woods says tourism operator RealNZ has reduced the Earnslaw steamer’s capacity from 400 to 250 and plans to replace its coal boilers so the boat runs on biofuel or electricity.

It’s not clear how these plans will result in transformational change in practice, however. An independent group will be formed to implement Queenstown’s plan, including representatives from the councils, DOC and Ngāi Tahu. But these bodies can’t force tourism companies to calculate their emissions or reduce them. Woods says the plan has the support of the industry, community and the mayor, and the future of the sector relies on its success. “If we don’t have a community that supports tourism, we won’t have a business.”

Jolanda Cave has been working for Ngāi Tahu Tourism for seven years and is now general manager, as the industry begins to rebuild. Photo supplied.

Queenstown Airport, meanwhile, is forecasting passenger numbers will increase by a third by 2032, as larger planes arrive. Then there’s Tarras. In 2020, Christchurch Airport revealed it had spent $45 million buying 750 hectares of farmland in the small town, half an hour’s drive east of Wānaka, and plans to build a new international airport, potentially increasing the emissions and number of tourists in the region. Most international tourists however, funnel through Auckland airport: 75 per cent of arrivals land there and it is likely to remain the main arrival point for the foreseeable future.

Other businesses appear to be onboard with the plan, however. Ngāi Tahu Tourism, one of the largest tourism companies in the country, is planning to not grow beyond 2019 numbers, general manager Jolanda Cave says. It has even axed some of its large bus tours to Glenorchy to reduce the impact on the community. “The more people, the more impact on our climate and on the areas that mean a lot to us, so less is better,” Cave says. “We need to generate a return because that provides a greater good [dividends go to the Ngāi Tahu iwi], but it’s more important that we do things the right way and we are challenged by our owners to live up to that.”

The company is also focusing more on domestic tourists, who have a smaller environmental footprint. Cave believes the industry as a whole is collaborating to make similar changes. “I think it’s very similar to health and safety. It is not a commercially sensitive thing, it is a good thing for everyone and that’s how we see climate sustainability and regenerative tourism. I think if we continue working together rather than against each other we’ll come up with some pretty great stuff.”

A Return Journey

In Te Anau, businesses are already reporting that it feels like 2019 again. After driving from Clyde, I arrived to a perfect summer’s day in Fiordland. Down at the waterfront, on an old wooden jetty I meet Adam Butcher, a fresh-faced man in an immaculate captain’s uniform. The former pilot bought his boat — a 1935 Glasgow motor sailer — in 2014 and started running Lake Te Anau tours two years later. When the pandemic hit, he kept the boat running to cater for Kiwis, but survived by working as a part-time cleaner and builder.

“The last three years have been particularly tough and morbid at times but we’re just starting to get back to the numbers we had prior to lockdown,” Butcher says.

In town, Chris Adams greats me with the kind of crushing handshake you’d expect from a Southland farmer. He started Fiordland Jet in 2017, going into business with a local crayfisherman. He also says the business has bounced back to pre-Covid levels.

He offered me a spot on the next trip boat ride down the Waiau River, which I gleefully accepted. But as the jetboat completed another 360-degree spin, I realised something was different about tourism now. In the two hour trip, I didn’t hear a single “yahoo”. The boat was almost entirely filled with unassuming South Islanders — and one moustachioed Romanian.

Around the country, tourism numbers are rocketing back. Queenstown Airport passenger figures were already up on pre-pandemic levels in October and were expected to be almost on par with 2019 over summer. International visitor spending meanwhile was actually up 2 per cent on 2019 in September, as tourists are staying longer and spending more.

But the tourists are different. International arrivals are still well down on pre-Covid levels, though Kiwis are travelling more and making up for the loss. Nationwide, international visitors in October were down 43 per cent on 2019, though that figure was expected to rise to 70 per cent of pre-Covid levels over summer. The Tourism Export Council forecast international tourist numbers would close in on four million by May next year.

The main issue for the industry has been a lack of workers. Ironically, it’s tourists on working holidays the tourism industry relies on to function. In 2019, 72,686 working holiday visa holders arrived in the country. By December 2022, only 22,284 had arrived and Queenstown alone was short an estimated 1500 workers. “It’s a real shame,” Chris Adams says. “A lot of the restaurants used to be open seven days a week and now they’re open five. But it will come right.” The Distinction Luxmore Hotel beside his business in Te Anau remained shuttered due to a lack of staff.

A few days later I was back in Queenstown on a busy holiday weekend with my family. Anticipating there wouldn’t be a free park in town, we took bikes and rode from Frankton, a 20-minute ride along a lakeside track. Along the waterfront promenade in town it was busy, but felt different. Not crowded, but vibrant. During the pandemic, much of the centre of town was pedestrianised. Downtown felt like it had breathing room. Weaving through the crowds on the boardwalk, we didn’t even need to dismount.

The following day we went back to Frankton but, avoiding the crowds, we biked in the opposite direction away from town and along the lake. We were soon swimming on a beach we had all to ourselves, watching as waves of aircraft came in low overhead, the roar echoing through the mountains.

Adam Butcher worked as a pilot in Fiordland before starting his own business when he bought the 88-year-old Faith in Picton and started Cruise Te Anau.

George Driver is North & South’s South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by support from NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the April 2023 issue of North & South.