Culture Etc.

Gorse blooms along the shore at Ōkārito lagoon. Photo: Thomas McLean.

Gorse! What is it good for?

From Chaucer’s time to our own, artists and writers have been enraptured and enraged by the spiky shrub.

By Thomas McLean

There’s a 1952 photograph by Gary Blackman that always gets me. Children Watching a Gorse Fire, Mt Mera, Dunedin shows a scrum of school kids in Dunedin’s North East Valley. I love the variety of expressions and the way Blackman captures the chaos and curiosity of youth. The cause of their glee and concern — a hillside fire — is beyond the picture frame, only present in the title. It’s an image that has stayed with me, and I often return to it in my writing (Blackman died in November last year, aged 92).

I first saw the photograph in 2004, on my first visit to New Zealand from southern California. Back then, there was only one thing about the photo I didn’t understand: What was gorse? Eighteen years later and now a New Zealand citizen, I understand why someone might watch with glee as a field of it burns.

New Zealanders hate gorse. It’s the farmer’s curse and the gardener’s nightmare. It looks pretty from a distance and smells buttery nice, but its monstrous thorns tear clothes and skin, and it’s almost impossible to eradicate. In the summer heat, gorse pods turn black and explode, firing seeds everywhere, which ensures ongoing environmental battles.

In some pockets of Aotearoa, communities are making a concerted effort to bring the spiky shrub under control. Over the past two years, volunteers have gathered in the West Coast village of Ōkārito to share a week cutting back the rampant gorse that is damaging surrounding wetlands. Armed with saws and herbicide, these so-called Gorse Busters have cleared 30 kilometres of shoreline of the thorny invader, making room for native birds to nest and flora to regenerate.

But New Zealanders didn’t always hate gorse. Pākehā farmers once welcomed it, and poets sang its praises. Its tenacity was appreciated, and it quickly became a familiar and admired element of the environment. In poetry, its spread across the landscape was closely associated with the spread of European culture — and the supposed demise of both Māori and of native flora and fauna. In recent years, as the impact of gorse on the environment has been better understood, poets and artists have captured our complex relationship with the farmer’s curse — one that shows no signs of ending.

Wordsmiths have been remarking on gorse since at least the time of the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer. Versions of a well-known saying “When the gorse is out of bloom, kissing’s out of fashion” can be found in Middle English, the medieval aphorism reflecting gorse’s long flowering periods along with the fact that several varieties bloom at different times in Britain. But the expression has taken on a new meaning in New Zealand, where Ulex europaeus often blooms twice per year.

Gorse appears frequently in English-language poetry, sometimes by its Scots name, “whin”, more often in the word favoured in the 19th century, “furze”. In Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s conversation poem, “Fears in Solitude”, the narrator is brought back from his hillside meditations by the “fruit-like perfume of the golden furze”. But while some writers celebrated gorse’s scent and colour, others highlighted its harsher side. In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the troubled anti-hero Heathcliff is described as “an arid wilderness of furze and whinstone”. Perhaps the most famous description of the spiky shrub occurs in Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native, where the resilient locals work in a “heathy, furzy, briary wilderness”, cutting and collecting gorse branches for fire fuel. Less seriously, but no less painfully, Winnie-the-Pooh’s very first adventure involves a fall from a honey-laden tree into a gorse bush.

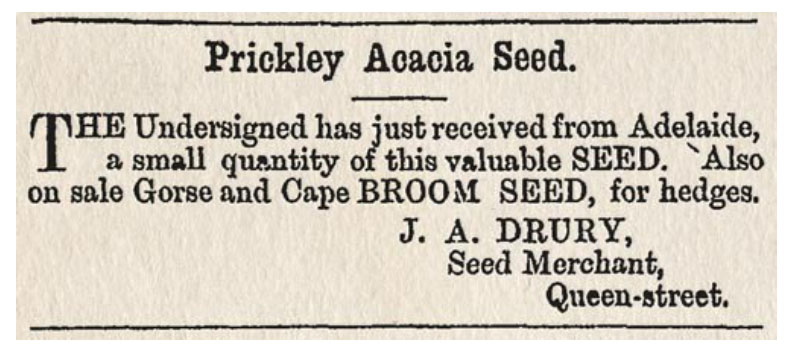

The earliest reference to gorse in New Zealand appears in Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle: in 1835, he recorded seeing “gorse for fences” at the Waimate Mission station in the Bay of Islands. Its use as a fence or windbreak soon received legislative support, and colonial newspapers advertised the sale of gorse plants and seeds.

In his 1884 poem, “The Canterbury Pilgrims”, Thomas Bracken (composer of “God Defend New Zealand”) celebrated the settlers who transformed the South Island landscape in just 30 years:

Behold their work!

Revere their names!

Green pictures set in golden frames,

Around the City of the Stream,

Fulfil the Pilgrim’s brightest dream;

With them a fairer England grew

‘Neath speckless skies of sunny blue.

Bracken’s “golden frames” were the gorse hedges that would neatly surround each green Canterbury canvas. But it was already apparent that gorse was far from picture perfect. Indeed, the novelist Anthony Trollope commented during his 1870 visit to Christchurch that the thorny shrub “has taken so kindly to its new home that it bids fair to become a monstrous pest. It spreads itself wide over the land and lanes, and unless periodically clipped claims the soil as its own.”

For some, the spread of gorse came to represent the spread of European “civilisation” across Aotearoa. In his 1901 sonnet “In Maui’s Island”, Scottish import John Liddell Kelly lamented the changing landscape:

And yet I note, with lurking discontent,

The dark bush dwindles, golden gorse spreads free;

So is the vigour of the Maori spent,

So thrives the fair-haired race from sea to sea.

May conquering and conquered blood be blent,

And breed new beauty and virility.

Kelly’s poem echoes popular, false ideas that the disappearance of Indigenous peoples and cultures was inevitable. In his sonnet, the changing colour of the landscape caused by the spread of gorse foretells larger cultural changes. This racist belief was widespread across Aotearoa (as well as the British Empire): think of all those remarkable Charles F Goldie portraits with distressing titles like A Noble Relic of a Noble Race.

But such poems were deeply misleading on another level, since they suggested that the spread of gorse (and Pakeha) was easy and inescapable. In fact, as historians like Tom Brooking have shown, it required a complete transformation of the environment. Imagine those early settlers arriving at their plots of (often confiscated) land. First, the trees had to be cut down; the land was burned to clear shrubs and tussocks; wire fences were installed to keep livestock out; European grasses were planted (along with some unwanted weeds, accidentally included in the seed mix); grass seed was threshed for resowing; wheat or turnips and other root vegetables were planted, as food and to break up and enhance the soil; and gorse might replace the wire fences, creating those poetic “golden frames”. And only then, when those cleared and transformed hillsides and landscapes were left untended or abandoned, the gorse broke free.

From one perspective, this transformation of the landscape is an astounding feat, and deserving of Bracken’s wonder. From another, it is appalling. In his early poem “Not by Wind Ravaged”, Hone Tūwhare sums up the transformation.

Deep scarred

not by wind ravaged nor rain

nor the brawling stream:

stripped of all save the brief finery

of gorse and broom; and standing sentinel to your bleak loneliness

the tussock grass— Oh voiceless land let me echo your desolation. [. . .]

Of course, in 1901, Tūwhare’s poetic revision of the colonial enterprise was a long way off. For much of the 20th century, writers simply saw the spreading gorse as a bewitching element of the New Zealand landscape, rather than a marker of past environmental violence. Katherine Mansfield, in her early poem “Vignette — Through the Autumn Afternoon”, describes a desire to escape “out of the city streets and on to the gorse golden hills”, from whence the whole city and harbour resemble “golden beckoning flowers”. As Janet Frame later wrote, “we learned to love those beaches and rivers and the long shadows of a Southland twilight and the golden roads lit on each side by the gorse hedges”. Many New Zealanders followed Mansfield and Frame in seeing gorse as a memorable and perhaps even essential element of our landscape.

A shift in our thinking about gorse has taken place in the last few decades. It’s a plant that needs sun to thrive; if you block the sun, the gorse dies off, and its longlived seeds have little chance to germinate. Even better, gorse’s root systems keep soil in place, and as they break down, they provide nutrients to whatever plant takes hold. This knowledge is of limited use in Ōkārito Lagoon, where the native flora never grow tall enough to shade the invader. But on the east coast of the South Island, at Hinewai Reserve on Banks Peninsula, native trees are very gradually overtaking the gorse that blooms across the hillsides. The transformation back to native growth will take many years, and there’s always a danger that fire could set back progress (gorse seeds are famously fire resistant). But eventually, the “gorse golden hills” of Banks Peninsula (and elsewhere) should turn green.

Chris Orsman has written thoughtfully about this shift in perception. In his poem “Ornamental Gorse”, the narrator describes the plant as “yellowing our quaint history / of occupation and reprise”. “[O]bsequious and buttery”, gorse is admirable “from a distance”, where its curves and colour among the hills seem to offer “a topiary under heavens / cropped by the south wind”. In the poem’s final lines, the flowering shrub becomes a religious martyr, “burnt” and “hacked” for our sins, as well as a national symbol: the narrator offers us “this crown of thorns” as New Zealand’s “reluctant emblem”.

So far as I know, few other poets have engaged with this more complex understanding of gorse. A number of visual artists, however, have done so, often with a hint of humour, suggesting that gorse is neither as wildly romantic nor as harmfully evil as past writers have imagined. The late Peter Nicholls created a series of striking sculptures that combined kauri with gorse as a kind of meditation on the necessity for the native and the exotic to work together. For one work, Consequential Landscape, Nicholls filled a beautiful kauri bowl with enormous brown and yellow ceramic gorse seeds.

Regan Gentry’s remarkable installation Gorse, of Course is a surreal collection of everyday objects — a broom, a bowl, even a mean-looking coat hanger — carved and created by the artist from gorse. Taking its title from a DH Lawrence poem (itself a riff on that medieval aphorism), Madeleine Child’s What if the Gorse Flowers Shrivelled and Kissing Were Lost? is a messy ceramic creation in white and gold that playfully mocks the farmer’s curse. Finally, Laura Marsh’s Home is Where the Gorse Is, a canvas bed with the title printed across it in black lettering, brings to mind the nostalgia of summer in the South Island with a more sombre echo of the stretchers that carried wounded and dead at Gallipoli.

Marsh’s title reverberates in another way. With determination and effort, some invasive species plaguing Aotearoa might well disappear in our lifetimes. Not so gorse which has, in places, made itself a permanent resident. Even in Ōkārito, where everyone seems to support the eradication of gorse from the lagoon, there are no plans to remove a thick inland growth of the spiky shrub that shields the village from flooding. Despite the efforts of Ōkārito’s Gorse Busters and the heroes of Hinewai, gorse isn’t going anywhere.

An 1862 advertisement in Auckland’s Daily Southern Cross offers gorse seeds for sale. Article clipping courtesy National Library of New Zealand, papers past.

Thomas McLean teaches English at the University of Otago. He has written about gorse, in a more academic vein, for the collection The Making and Remaking of Australasia (Bloomsbury, 2022).

This story appeared in the February 2023 issue of North & South.