Small Town, Big Sound

Lyttelton has a population of 3000, but probably has more award-winning musicians per capita than anywhere in the country. George Driver travels to the port town to find out why.

By George Driver

Adam McGrath was 29 when he moved to Lyttelton, quit his day job mowing lawns at a Christchurch high school, and decided to just play music. A few years earlier he’d travelled to the United States, to the home of the folk and country music he loved. After two years of wandering, he returned home on a visa run and was staying in Lyttelton when he unexpectedly found a path to follow.

“I was trying to find a place,” McGrath recalls. “To figure out who I was and what I should be doing. I figured out that even though I was coming from this tradition it would only be of service to me if I did it in New Zealand. The source is in me and how I relate to the world.”

He decided to stay and got a job as caretaker at Phillipstown School. While grappling with this epiphany, he met up with Lyttelton musician Lindon Puffin, who was making a living playing his own music and touring small-town New Zealand. This, McGrath realised, was the way.

“I knew making a living touring was possible in America, but I didn’t know you could do that here,” McGrath says. “Back then, when people went on tour they went to Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and maybe Dunedin once a year. Lindon was just burning around the country singing his own songs in the most random of places. I thought, let’s give that a nudge.”

Then musician Delaney Davidson knocked on his door. McGrath had initially met Davidson at a gig a couple of years earlier. When he knocked on McGrath’s door he told him he should meet this banjo player, Jess Shanks. “A couple of days later I met Jess and we played our first show that night. Both of us were about to turn 30 and we thought maybe this is our last chance to have an adventure. So we decided to quit our jobs and do nothing else but play music. It’s pretty hard to find someone who says this is all we’re going to do and see what happens. And we’ve been doing that ever since.”

Shanks herself had recently been encouraged to play more music by Davidson, who she’d gone to high school with in Christchurch. “I wasn’t a performer and wouldn’t have called myself a musician,” Shanks says. “I played, but I never had the courage to be on stage. I just had a guitar and a banjo, but Delaney encouraged me to sing and play my own songs and at the end of that summer he introduced me to Adam and we had this affinity.”

“There was a tight-knit community and a real diversity and tolerance. I just loved the place.”

McGrath and Shanks formed a duo that expanded to become The Eastern, a folk-country-punk-Americana band now known for playing hundreds of shows a year, often in rural backwaters usually untouched by the sound of the touring musician. The band became a cornerstone of Lyttelton’s folk scene, operating as a kind of creche for talented musicians finding their feet. Past members and collaborators include Marlon Williams, Hannah Harding (Aldous Harding), Reb Fountain, Anita Clark (Motte), and Adam Hattaway (Adam Hattaway and the Haunters).

But they are just one cog in a music scene that has changed New Zealand music forever and has reverberated around the world.

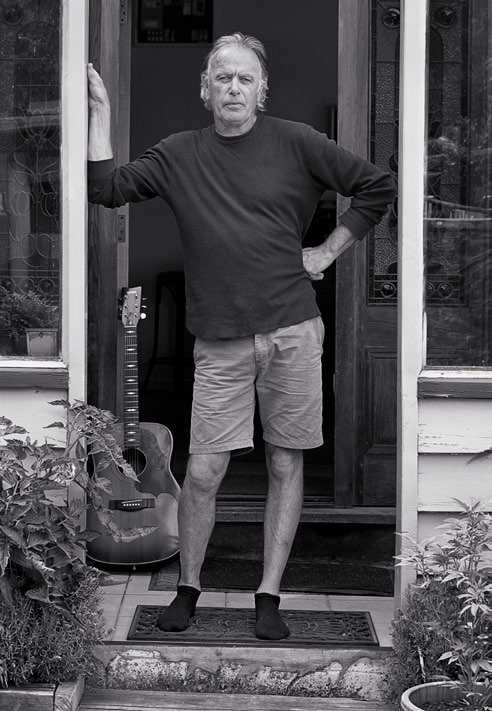

Adam McGrath, left, has been touring Aotearoa with The Eastern for the last 17 years. Photo: Supplied

THE PORT TOWN

Lyttelton’s different. It’s just a 20-minute drive from the Christchurch CBD, through the longest road tunnel in the country, through the Port Hills. But when you come out the other side it feels like another world. The first thing that hits you is the port — the largest in the South Island — which looms on a superhuman scale, dwarfing the town with its steel cranes, stacks of logs and concrete piers reaching out to ships the size of apartment blocks. While Christchurch often feels like a grid on a sprawling plain, much of Lyttelton is near vertical, clinging to the side of a 10 million-year-old volcano and looking south over the turquoise harbour at the golden hills of Banks Peninsula. The old weatherboard houses are in an amphitheatre-like basin, so it feels like everyone is looking in on each other.

One side bathes in afternoon sun, the other shivers through winter.

Al Park moved to Lyttelton in 1978, buying a four-bedroom “dilapidated shack” with an outside toilet on the dark side of town for $3000. A year earlier, Park had started a New Wave and punk venue on Mollett St, an alley in central Christchurch, and was touring the country with his band Vapour and the Trails.

When Park first moved over the hill, he says Lyttelton was rough and very much a port town.

“It used to attract the outer fringe of society, and the British Hotel was kind of a safe haven and there were sailors there from around the world,” Park recalls. “Because it’s a port, it had that atmosphere that you could be anywhere in the world.”

The cheap housing and dramatic landscape also attracted an arts community. Photographer Laurence Aberhart lived there and artist Bill Hammond lived next door to Park. “There was a tight-knit community and a real diversity and tolerance. I just loved the place.”

Al Park has been called a father figure of the Lyttelton music scene and a 2019 tribute album, Better Already — the Songs of Al Park, featured McGrath, Delaney Davidson, Marlon Williams, Jordan Luck, Barry Saunders and Adam Hattaway. Photo: Tony Gardiner

Delaney Davidson, who has a 100-year-old two-bedroom white weatherboard cottage above the town’s Anglican cemetery, recalls Lyttelton being “kind of weird and gangy”. He mostly grew up in Christchurch but lived in Lyttelton for a period when he was a teenager in the 1980s after his parents split up. His dad was there, moving from place to place, housesitting. “I lived in about 13 houses in a year and remember trying to sleep in these rooms that felt like fridges,” he says. “The docks were open, you could walk out freely on the wharves. There were a lot of sailors roaming around. There were seven or eight pubs. It was a real working port town.”

The abundance of pubs meant there was regularly live music in Lyttelton, but nothing that could be described as a “scene”. Park says this changed in the late 2000s, when it began to crystalise around a kind of gothic folk music and Americana. The Eastern, formed in 2006, had a residency on a Wednesday night at the Wunderbar, a popular music venue established in the early 1990s. “There wasn’t anyone else playing folky country music at the time,” Shanks recalls. “It felt like quite a different thing and at first we didn’t even know where to play shows.”

The folk scene soon gained momentum. Local musician Harley Williams (The Tiny Lies) started a bimonthly gig called the Harbour Sessions, showcasing Lyttelton music. A 2009 documentary on the Harbour Sessions features a teenage Nadia Reid, visiting from Port Chalmers, and a local teenager who worked stacking shelves and serving ice creams at the London Street Dairy: Marlon Williams.

Park first saw Williams play during a Beatles-themed Sunday afternoon open mic at his bar in Christchurch, Al’s, in around 2006. “He was about 15 and he got up and everyone went nuts,” Park says. “He ended up doing five songs. It was like, wow. I’ve known lots of musicians in my time, but Marlon was the only person I’ve ever met who truly had that star quality.”

Adam McGrath had a similar encounter, when he saw Williams playing at the old Lyttelton Times building with his long-time collaborator, Ben Woolley. “They were singing Simon and Garfunkel and they had the harmonies down and I thought, ‘Who is this guy?’. He was like the golden child. Everyone was like ‘This is the guy’ and you just knew it.”

In around 2007, McGrath headed into Christchurch on a regular busking run. He went to his spot in City Mall, the pedestrian strip in the CBD, but a teenager was already there playing.

“She was singing a John Prine song that I sang so I said ‘Let’s play it together.’ I think she was living in Geraldine and selling cherries in between busking and she came to the Wunderbar in Lyttelton that night and joined the band and started singing with us.”

The teenager was Hannah Harding, years before she’d adopt the stage name Aldous Harding and become one of the country’s most successful contemporary musicians. “She was immediately the most naturally talented, powerful creative spirit that I’d ever seen.”

Delaney Davidson, meanwhile, had spent a decade living between Switzerland and Aotearoa, touring with a band called the Dead Brothers in Europe and travelling home to play in the Southern Hemisphere summer. “I don’t think I paid rent in 10 years,” he says. “I was on tour the whole time.” His mother lived in Diamond Harbour, a short ferry ride across the harbour from Lyttelton, and he started to become more involved in the music scene developing across the water. Then he went to play a gig at the Wunderbar, filling in for The Eastern, that would change his life. Marlon Williams also showed up at the venue with his guitar — they’d been double booked. But the pair soon realised they knew many of the same songs, so played the night together. That led to planning a collaboration and on the morning of 22 February 2011, Davidson decided to change his travel plans and to stay on in Lyttelton instead.

Suddenly there were multiple generations of musicians in the small town — veterans and the up-and-comers — all touring and playing shows in Lyttelton’s abundance of bars, driving each other, creatively feeding off one another, forging a life out of music. Then everything changed.

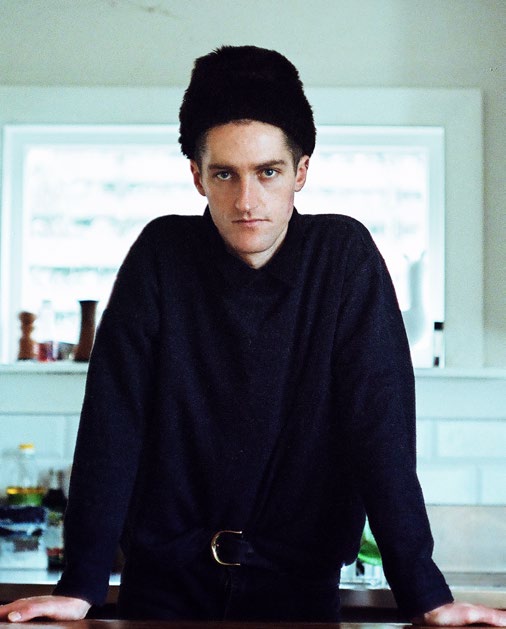

Singer, writer, connector Delaney Davidson at home. Photo: George Driver

SHAKE RATTLE

AND ROLL

Having that morning cancelled his ticket to Europe, Davidson was with Williams to discuss a collaboration on a “haunted country album”. The pair met at the Lyttelton Coffee Company in the town’s main street just after noon. Across the cafe, Al Park was having a cup with Barry Saunders of the Warratahs. Then the earth began to shake.

The earthquake struck on a Tuesday at 12.51pm and was centred more or less beneath the Lyttelton Tunnel. Unlike in the earlier Christchurch earthquake the previous September, this time Lyttelton’s colonial main street was decimated.

The tunnel was temporarily closed, the road over the hill to Sumner was impassable and Lyttelton’s music community was thrust together in a crisis, looking for a way to help.

When the tunnel reopened later that week The Eastern, Davidson and Williams headed to a park in Christchurch’s Brighton and met up with another musician, Tami Neilson. The country singer was touring and due to play Lyttelton that night. Together, Nielson, The Eastern, Davidson and Williams put on a free show instead. “It focused things,” Davidson says of the post-quake period. “Music felt really fundamental to life. You could see it and feel it changing people’s lives. No one wanted sport. They all wanted music. Music’s about deep connection, I think. That’s what people wanted, solace.”

The Eastern went on a local tour, playing over 50 free shows in backyards around Lyttleton and Christchurch in a month. One weekend they played 13 shows. Lyttelton house parties sound like they became some of the best music festivals in the country, as bands traded playing in pubs for lounge rooms and street corners. Al Park’s bar in the city was closed by the earthquake so he started putting on gigs at the Naval Point Club, Lyttleton’s yacht club, which was left unscathed by the quake. “The earthquake was pivotal for the music scene,” Park says. “We all knew each other already but it really brought everyone together. The unity we got out of it was quite fantastic and it still lasts. There’s still a really strong bond among all of those musicians.”

Adam McGrath says in the week following the earthquake, The Eastern and the Unfaithful Ways (Marlon Williams’ band at the time) went to Gore to play the Hokonui Moonshiners’ Festival, where he got an idea. “I looked at Marlon when he came off stage and he was crying,” McGrath says. “He was totally shattered by the week and he said ‘What are we going to do?’ I said we’re just going to play music. After playing that day we decided to do an EP together to sell for charity, as something we could do to help. Then we ran into Delaney, so we included him, then we thought, let’s include everyone.”

A group called the Harbour Union was formed, including Davidson, Williams, Park, McGrath, Jess Shanks, Lindon Puffin and other Lyttelton musicians, and they recorded a self-titled fundraiser album, gaining national attention. Then Lyttelton entered an era of recording that would take their music around the world.

Making music: producer Ben Edwards in his studio, the Sitting Room, with Marlon Williams in 2016. Photo: Supplied

THE PRODUCER

Ben Edwards was celebrating his birthday when the earthquake hit. He had opened a recording studio in Christchurch around 2005 after moving back home from Melbourne, where he had pursued a music career. He started the studio with a friend, planning to record each other’s solo music, but soon other musicians began knocking on the door. The Eastern recorded their first album in the studio and the Unfaithful Ways started using it as a practice space, then recorded their first album there too. With no formal training in recording or producing, Edwards began honing his craft.

His studio was destroyed in the September 2010 earthquake. He found another space, then that was destroyed in the February quake. He was enlisted to record the Harbour Union album in a house in Lyttelton and was then scheduled to record an album with The Eastern but was still studio-less. McGrath, however, wrangled permission to record Hope and Wire in a red-zoned house in Christchurch’s Dallington. “I moved in there with my dog to look after the gear,” Edwards says. “It was awesome. There were no houses around and we could do what we wanted.”

“Marlon was playing free every Wednesday night and Hannah was playing free every Tuesday night, both to like five people, often with some guy shouting in the corner”

Davidson came along and was also inspired by the space too, and recorded his collaboration with Marlon Williams, Sad But True Volume One, in the house with Edwards, the first in an award-winning three volume series.

While looking for a new space, Edwards bought a house in Lyttelton and began converting the garage into a makeshift studio. It was just as Lyttelton’s music scene was hitting its straps in a post-quake surge of creativity.

The Eastern was garnering national attention, Marlon Williams had left Unfaithful Ways and played and toured with The Eastern as he found his feet as a solo performer. Williams and Davidson’s collaborations were also getting attention; Hannah Harding had left The Eastern and, as Aldous Harding, was honing her solo craft too. Harding and Williams were playing regularly in town, sharing weekly slots at the Porthole container bar, playing to a handful of people.

“Marlon was playing free every Wednesday night and Hannah was playing free every Tuesday night, both to like five people, often with some guy shouting in the corner, and someone’s mum telling them to be quiet, and Marlon singing away,” Delaney recalls.

In December 2012, Edwards recorded Harding’s first album, Aldous Harding, in the basement of the Wunderbar, as he was still establishing his own studio space. Although, as Edwards recalls, the album was almost abandoned. “She was really struggling with her anxiety,” Edwards says. “We had her booked to record and she didn’t turn up, didn’t answer her phone and didn’t answer it the next day or the next day. It turned out she’d thrown her phone in the sea and went to Nelson. She said it was too scary. We rescheduled and Delaney and I were going to produce it, but again the same thing happened. The third time, her and Marlon were quite close, and I asked if he’d like to help and try and physically get her to the studio, so that’s how he co-produced the record.

“It was quite heavy, but it was fucking awesome.” The album launched Harding’s career, gaining international acclaim and was nominated for the Taite Music Prize and Silver Scrolls. Al Park recalls Harding’s earlier performances could be “pretty loose”, but leading up to recording the album something changed. “She was in an environment where her talent was encouraged,” Park says. “By the time she went to record, something snapped in her to make her focus. She was channelling all of her energy into it.”

Marlon Williams. Photo: Supplied

Aldous Harding. Photo: Emma Wallbanks

In 2014, Edwards recorded Nadia Reid’s debut album, Listen to Formations, Look for the Signs, which was nominated for a Tui award and the Taite Music Prize. The same year, he recorded Williams’ first solo album, Marlon Williams, which led to him winning the Breakthrough Artist of the Year award at the 2015 NZ Music Awards and another Silver Scroll and Taite nomination.

Artists around the country, and around the world, began to take note. Reb Fountain, Tami Neilson, Hopetoun Brown and Don McGlashan have since recorded with Edwards in his garage studio, now named the Sitting Room. Prior to the pandemic, about half of the bands he worked with came from overseas to record, many from Australia. Edwards went on to win Producer of the Year at the 2017 NZ Music Awards for his work on Reid’s second album, Preservation.

“His personality is a big part of that success [of Lyttelton music],” Shanks says. “He cares so much and he’s so passionate. With his openness, there’s an emotional bond that happens too.”

The artists that helped create his early success have moved on. Harding recorded her later albums with producer John Parish in Wales, who is renowned for his work with PJ Harvey. Williams’ latest album, My Boy, was recorded at Auckland’s Roundhead Studios and produced by Tom Healy. His previous solo release, Make Way for Love, was written at Edwards’ studio and preproduced there, but was ultimately recorded in California. Reid’s latest album was recorded in Richmond, Virginia.

Edwards has mixed feelings about this. “It makes me feel proud and sometimes a bit shitty,” he says. “Of course I would love them to be here. But you know that’s not the right thing for them. You know they’re now into that next tier. So it’s like that was your job. You kind of thought you had this thing with them forever and you do, they’re always your mates. They’ll come and do demos — Marlon’s going to come and do a te reo album — so you did your job, but I didn’t realise that was the job. You do have to say goodbye to your kids.”

Williams left Lyttelton for Melbourne in 2013 — Al Park held a fundraiser gig to help get him established in the new city — and for a time he lived above the Yarra Hotel pub with then-partner Harding. Their breakup later produced two of New Zealand’s great albums — Harding’s Party and Williams’ Make Way for Love, which featured the 2018 Silver Scroll-winning song, their plaintive duet, “Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore”.

A NEW BEAT

Lyttelton’s different now. The Eastern are still touring, although not at the frenetic pace they used to. McGrath now lives over the hill in Heathcote. Jess Shanks started a venue called Blue Smoke in Woolston for a few years but is now based back in Lyttelton. Harding moved to Wales for a few years but now has a place at Diamond Harbour, across the harbour from Lyttelton, and is on a 27-date European tour. Williams is based in Lyttelton and has recently wrapped Australasian dates off the back of a European and North American tour.

Delaney Davidson and Ben Edwards are still in town. Edwards recorded Don McGlashan’s latest album, Bright November Morning, featuring Shayne Carter. Reb Fountain is also booked to record another album soon.

The main street of Lyttelton is still pocked with vacant sections where the heritage buildings were destroyed by the quake. The Wunderbar has new owners and isn’t the folk hub it used to be. The scene is changing.

“The rest of New Zealand think that we all sit around and have dinner every night together, me, Adam McGrath, Marlon Williams, Hannah Harding,” Delaney Davidson says. “But it hasn’t been like that for years. People still have this Lyttelton folk-scene concept, that everyone in Lyttelton has a beard and tattoos.”

Ben Woods has never played in The Eastern. Last year the 28-year-old released his second album, Dispeller, which was recorded at the Sitting Room with Edwards. It’s a fantastic warbling, rich and atmospheric record, like listening to the Velvet Underground record at half speed, with Woods’ baritone croon on top. Growing up in Lyttelton and interested in punk and alternative rock, he says he didn’t see a place for his music there. “I remember thinking ‘what is this weird Americana thing happening?’ It buzzed me out massively.

“I feel like all of those people who came from playing together around the earthquake, doing the hardcore country thing, there’s been a lot of branching off into different sonic territories, which I think is healthy. For me, it makes me feel a little more comfortable. I just didn’t feel like it was a place for me at all. Although now I’m just open to more things and not so insecure and think it’s all great.”

Violinist Anita Clark who was in The Eastern, went on to play in a string of Lyttelton bands, including” a group called the Greyhounds with Marlon Williams. She now plays in Don McGlashan’s band and tours with the Phoenix Foundation, as well as playing ethereal tunes under the name Motte. Her latest album, Cold + Liquid (again, produced by Edwards), includes recordings from inside the hold of a cargo ship at the port. Clark says she struggled to write her own music during Lyttelton’s folk boom. “The Eastern was an emotionally draining band to be involved with that limited my capacity to do other creative things,” Clark says. “It also felt like there was a huge pressure being around so many great songwriters, like I was missing out by not writing my own music.” It wasn’t until she moved to Christchurch for a period that she was able to focus on song writing.

“Can you do this? Yes, I’m evidence. Just enjoy your life. It sounds dumb, but it’s true. I’m not saying you should quit your job and start a band, but you could.”

For others, however, the competition among artists and the opportunity of playing 200-plus shows a year as part of The Eastern appear to have been a key ingredient in the music scene’s success. “Adam deserves a lot of credit for what happened in Lyttelton,” Park says. “He loomed large for quite a while. He’s probably had the least amount of success but has had so many people run through that band that have gone on to become so successful.”

Edwards calls the band “the crucial glue” of Lyttelton music. “Marlon wouldn’t understand touring or have his work ethic if he hadn’t had time touring with The Eastern.”

“It had huge amounts of possibility for people to become part of that travelling show,” Davidson says. “It’s like running away with the circus.”

There were other key ingredients. Park has been called something of a father figure of the scene. “He’s a testament to sheer bloody mindedness and dogged tenacity,” Davidson says. “He’s got energy, he’s fit and he’s going for it.”

Park himself recalls giving Marlon Williams a lift to the University of Canterbury, where he was studying and trying to convince him to drop out to play music. “I told him, ‘Truly, you don’t need to worry about it [studying].’ To me, he was just someone who was always going to succeed.”

McGrath, meanwhile, says Davidson was the key encourager — the person who made things happen and told people to give music a go. “Delaney burns,” he says. “He has a lot of energy and he wants to do stuff and gets stuff done and that’s contagious and he’s not afraid to tell people things.” Of course, that’s how The Eastern started.

There was also a culture — an ethos that developed, valuing music as a career path, foregoing financial security for the love of music. “Everyone was committed to music,” McGrath says. “That was the special thing.”

Edwards says that’s also involved shunning the materialistic goals prevalent in middle New Zealand. “We don’t give a fuck about the pressure of having to have the latest car, or the latest thing. I don’t have a flash phone. I have my mum’s old iPhone 6. The TVs in this house were free. I don’t care about that shit because it doesn’t matter. None of my cars have cost more than $2,500. I’d rather have a life and so that’s what I want to do. Edwards says that’s also involved shunning the materialistic goals prevalent in middle New Zealand. “We don’t give a fuck about the pressure of having to have the latest car, or the latest thing. I don’t have a flash phone. I have my mum’s old iPhone 6. The TVs in this house were free. I don’t care about that shit because it doesn’t matter. None of my cars have cost more than $2,500. I’d rather have a life and so that’s what I want to do.

“Can you do this? Yes, I’m evidence. Just enjoy your life. It sounds dumb, but it’s true. I’m not saying you should quit your job and start a band, but you could.”

Photo: Emma Wallbanks

Photo: Hayley Theyers

Last year, Ben Woods took the step to make music his full-time pursuit, cutting back hours in hospo to have time to write and record his next album. It was a step he says he took after a similar pep talk with Edwards.

“People feed off each other, people are driving each other, so it’s easy to take it seriously,” Woods says. “There’s definitely moments where I’m like ‘What have I done?’ Especially when you start getting older and you think holy shit, my friends have masters degrees and PhDs and houses and kids and I’ve got these three albums that I’ve spent all of my money on. It’s a sacrifice that’s for sure.”

While Davidson says much has changed over the last decade in Lyttelton, when I talk to Jess Shanks she’d been at a dinner party the night before with Davidson. They’d then headed down to The Commoners Bar, in the basement of the old British Hotel, which doubles as a Nepalese restaurant. Al Park has run an open mic night there every Wednesday for the last few years. That night, Marlon Williams was there and got up and performed. A couple of weeks earlier, there was a gig at The Commoners with Davidson, Williams, Harding and Woods in attendance. Shanks says it has that feeling again, that a scene is beginning to bubble.

“There’s really cool music happening now, particularly this last summer. The old way we used to hang out, getting out the guitars and playing together, playing impromptu shows and jamming. It feels like it’s back. Like with the earthquakes, this feels like the ‘coming out of Covid’ time. And there’s a younger generation coming through.

“It feels really alive again.”

Lyttelton musicians perform at The Eastern’s 10 year anniversary show at Blue Smoke, including Marlon Williams, Lindon Puffin, Reb Fountain, Adam McGrath, Jess Shanks and Flora Knight. Photo: Supplied

Listen Up

A guide to some quintessential “Lyttelton sound” tracks.

Ben Woods “White Leather Again” | Marlon Williams with Aldous Harding “Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore “ | Aldous Harding “Imagining My Man” | Marlon Williams and Delaney Davidson “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” | Delaney Davidson “Sleeping Woman” | The Eastern “Hope and Wire” | Motte “Only” Al Park “California” | The Harbour Union “Little Mountain Town” | The Unfaithful Ways “Trouble I’m In”

Type into your browser: rb.gy/aabyiq for a free Spotify playlist.

George Driver is North & South’s South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by support from NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the May 2023 issue of North & South.