En Pointe for 70 Years

The Royal New Zealand Ballet turns 70 this year. In a discipline usually thought of as glamourous, graceful, and competitive we instead find tenacity, sheep droppings, and collaboration in its story.

By Gabi Lardies

A scene from the 1965 production of Giselle, with set and costumes designed by Raymond Boyce. Photo: John Ashton. All other images supplied.

OVERTURE

In the beginning, there was a Danish émigré moonlighting as a taxi driver. It was 1953 and in that year Poul Gnatt established the New Zealand Ballet.

Gnatt, a dancer born in Vienna to Danish parents, had toured New Zealand with an Australian ballet in 1951. He looked around at our mountains, people, sea, and beaches and said “a beautiful country, but without a ballet company!” He couldn’t let this be — in 1952 he moved to Auckland with his young family, drove a taxi and taught ballet. Gnatt was considered to be kind, charismatic and strong-willed. In recollections gathered for the book The Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60, his enormous tantrums are remembered, some of which ended in throwing coffee mugs at walls. But mostly, his legacy is one of nurturing talent, and changing lives.

Memories of the nascent company’s first tours are marked with sheep droppings, tufts of wool, piles of wood, plagues of crickets, sunburn, loudly flushing toilets, and the tour bus, a Commer van. At auditions, aspiring dancers would be asked “Can you drive a truck?”

In the first decade of its life, the company was a stalwart band of dancers who toured to 125 different venues from Kaitaia to Bluff. “Venues” is an inclusive term — local halls, fruit packing sheds, theatres with said loud toilets underneath the stage, and schools full of rowdy kids. In 1950s New Zealand, it was for many in the audience, no matter their age, their first taste of ballet. And they loved it. The tours relied on grassroots support — local billets would not only host the dancers and crew, but advertise the show dates, help iron the costumes, and donate money for petrol to get the van and the props truck to the next town. People need more than sheep and rugby balls for a national culture; they also welcomed art, storytelling and magic. And that, the company provided in spades.

Company founder Poul Gnatt building a set in his backyard in Sandringham, Auckland in 1953.

The fledgling company on tour, 1959.

ACT I: PAS DE DEUX

In 1958, an 18-year-old boy from Petone, with a flair for pirouettes and an “extra good jump” joined the company. Jon Trimmer had been perfecting his pirouettes at his eldest sister Pam’s ballet school. “It seemed as if I was made for dancing,” he says today after an extraordinary career spanning six decades — almost in fact, the entire life of the Royal New Zealand Ballet company.

In the late 50s, Trimmer was one of nine dancers, who, as well as driving trucks, “had to put up all the scenery, and change the scenery during the performance, and then take it all down again at night and pack it in the truck”. Sometimes, there was not enough room for all the scenery on the stages, and some stayed on the truck. But this was a small trade-off for being able to perform in small venues. “They’re really pretty good. The small venues are a lot of fun to play in, even if they don’t have everything you need,” he says.

Sheep were proxy members of the company: in one town they shared the dressing rooms, in another their droppings had to be swept off stage, and between towns the Commer would stop when big tufts of wool were spotted on wire fences so ballerinas could collect it to pad the tips of their pointe shoes. Livestock and all, Trimmer, now 84 and knighted in 1999 for services to ballet, describes the tours as “wonderful, absolutely wonderful”.

When asked to select a favourite memory Trimmer says, “Oh heavens, there are so many of them.” Once he takes a minute to sort through over 60 years of memories, Queen Elizabeth II comes forward. In 1977 the ballet company performed part of Paquita for her in the Christchurch Town Hall, alongside orchestras and choirs. Paquita dates back to 1846 and tells the story of a complicated love between a Spanish gypsy and a nobleman. All ends happily, with a grand finale and triumphant close — it is this part which the ballet company performed. Dancing alongside Trimmer was a new, 16-year-old member of the company, Kerry- Anne Gilberd. She was “like the baby of the company”, says Gilberd. “Everyone looked after me. It was very much a family. [Trimmer] is always a pleasure to dance alongside. We did a little solo together — 32 fouetté.” One can only imagine the enthusiasm, and fitness, needed to spin on one leg, and whip the other one around, that many times continuously.

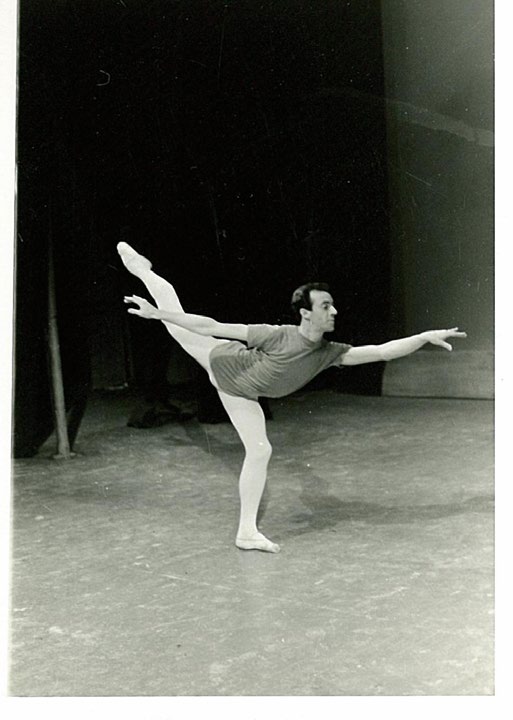

Jon Trimmer rehearsing in 1967. He would dance with the RNZB for 60 years.

INTERMISSION:MAGIC AND MEOWS

Trimmer had other tricks beyond the endurance fouetté. In the 1987 production of The Nutcracker he danced as Uncle Drosselmeyer. Onstage with him for part of the ballet was a little extra, dancing as a mouse. Clytie Campbell started dancing so young that the bodice of her first tutu was small enough to be made from a repurposed velvet hat. The eight-year-old Campbell thought Trimmer was a magician “because he would pull candy canes out from the back of your ears”.

Campbell already knew Trimmer, as her mother, Philippa Campbell, a former ballerina and dance teacher, is part of the community woven around the company. Trimmer and his wife Jacqui Oswald, a distinguished ballerina in her own right, would stay with the Campbells when touring in Auckland. They brought with them a troublemaker in the shape of a marmalade cat called Thomas. “Their cat didn’t get on with our cat,” Clytie Campbell remembers. “He was meant to stay shut in the front room, but I remember him getting out and having a few fights around the neighbourhood.” Even now she laughs about it.

Kerry-Anne Gilberd as Odile in Swan Lake, 1985 — her Kristian Fredrikson-designed costume is now in The Dowse Art Museum.

ACT II: VARIATIONS

“We made our entrance breaking in through the doors, and we’d run into the centre of the stage and stand there. I can always remember that there was silence, and then the audience would gasp,” says Kerry-Anne Gilberd. It was in 1985, that the ballet staged, for the first time, a full production of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Then a principal dancer, Gilberd was cast in the leading dual roles of Odette and Odile. “I played the baddie — baddie Baron,” says Trimmer of his part as the evil sorcerer who casts a spell on the princess Odette, turning her into a swan by day. In this scene, the pair arrive into the royal ballroom, “big and lavish, with lots of columns”, where prospective brides have been gathered for Prince Siegfried.

In the role of the black swan Odile, Gilberd wore an intricate black tutu, which she still regards as the most beautiful garment she’s ever worn. “It was spectacular, it always gave me a lot of confidence to be in that costume.” Created by the lauded stage and costume designer Kristian Fredrikson, the tutu used the end of a bolt of vintage lace which he had acquired in New York. The fabric had history: it came from the same bolt that had been used in the 1920s to make a costume for actress Greta Garbo. Gilberd remembers Fredrikson had stashed this fabric away for years, and that there was barely enough to make one costume — “and it was mine, I was very fortunate”. The lace in question is fine and embedded with silver sequins, which shone under the stage lights — it’s now part of The Dowse Art Museum’s collection. The tutu is also a favourite of Hank Cubitt, senior costumier of the present company. “The fabrics that [Fredrikson] used, and the layering techniques are just beautiful. The fabric was absolutely blinging off the stage.” This glowing commendation isn’t gained easily — Cubitt is extremely discerning: he once called for beanies to be eradicated, claiming they have no style.

The Dowse holds more than 70 of Fredrikson’s costumes and drawings. “Kristian Fredrikson was the master,” says Tracy Grant Lord, early one cold morning before heading to a rehearsal, where she will make adjustments to the props, sets and costumes she has designed for a theatre show, part of the Auckland Arts Festival. Grant Lord is a leading production designer, scenographer and costume designer, highly regarded here and internationally for the sumptuous and detailed worlds she creates on stages for ballet, theatre and opera. “I was very fortunate to be inside companies at the same time [Fredrikson] was. We weren’t able to work together — because we were both designers — but often I would be coming in to work on a show, and he would already be there working on the show that was happening, so we crossed over.

“I was around when they were making Swan Lake, which is a legend. I couldn’t believe the intricacy of it. You know, I was absolutely flabbergasted. It was wonderful to see that level of expertise.”

The gasp-worthy costumes for that first full production of Swan Lake didn’t come into this world without drama. The dress rehearsal was underway at The Opera House on Manners St, Wellington, while six blocks away at the company’s Vivian St studios, sewing machines were still running, finishing the costumes for Act II. As soon as threads were tied, costumes were thrown out the second storey window into the arms of a waiting courier, who then ran to the theatre. The dancers were sewn into the costumes in the wings.

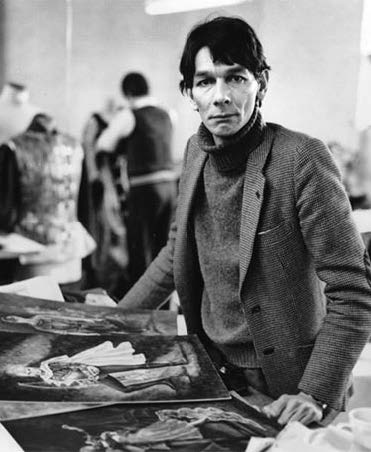

Wellington-born Fredrikson was a journalist before becoming a lauded opera and ballet production and costume designer here and in Australia.

INTERMISSION:

COSTUME CHAOS

Hank Cubitt’s never had to throw costumes out of a window, but he has had moments of panic. “The most chaotic thing that happened to me was on tour. I washed a whole lot of white garments — lots of them, we’re talking 15 to 20 costumes — and there was a green singlet. I did not see the green singlet. When I opened up the washing machine, all the garments were green, it was sort of an apple green tone. Well, that was not what we needed for that night. I was in panic. It was probably my most heart-stopping moment because I was new at the time.” Luckily, Cubitt found dye remover at the local Spotlight and, “the show went on, with no one knowing that apple green could have been the colour of the day”.

Hank Cubitt started his career as an apprentice cutter. Cutting is still the skill which he finds most rewarding.

ACT III: CODA

The little mouse, Clytie Campbell, performed again with the magical dancer. Campbell remembers holding hands with Trimmer on stage in 2013 in Don Quixote, the ballet adapted from the Spanish epic novel. Trimmer was the titular character, “a mad Spanish Don”. The Don is revealed to be in search of a woman, Dulcinea, with whom he was entranced. Campbell played Kitri, an innkeeper’s daughter running away from an unwanted betrothal. She catches the Don’s eye, who claims her as his Dulcinea. He attempts to woo her by partnering her in a minuet — an elegant couples dance. “We had one little dance where we had to hold hands, do a step together and then back. It was so nice to do even that small thing with him,” says Campbell, “I have photos, bad photos, of it somewhere.”

Campbell can’t decide on her favourite role. Some she has loved for the form of the dance itself, “because they’re beautiful pieces”. Some for the mastery required. “Sometimes you have the freedom to really move — to fly and jump. It’s really physically challenging, and you feel a real sense of achievement having done it.” And others for the portrayal of character. “[Romeo and Juliet’s] Lady Capulet, she’s a super fun character — you have fake blood on your hands, and you scream, silently of course. It can be really, really, dramatic. Those ones are fun.” On the last point, Trimmer agrees, “I loved playing the witches. Oh, they were such fun.” He preferred, though, to charm in more traditional ways — his favourite role was the prince in Giselle.

Like Trimmer, Campbell loved touring the small towns of Aotearoa. It was 2005 when she joined the company (at full height this time), after eight years of dancing in Europe. It was the national tours that were the point of difference between the homegrown ballet company and the European ones she was used to. The RNZB has stayed true to its roots and continues to tour to small towns, with programmes such as Tutus on Tour. “I loved that we toured around New Zealand, I saw places in my own country that I’d never been to,” she says. It was about the people too. Campbell found family, and family friends, in the audiences. “People that knew me when I was younger would come and watch the show — it was really nice to perform to people that knew you.”

Production designer Tracy Grant Lord is based in Auckland but visits the ballet’s Wellington headquarters multiple times during a production.

Today, tours no longer require dancers to be loading props at midnight. The dancers — the ballet’s current company numbers some 36 performers — come with infrastructure and a team. There are professionals to take care of the costumes, the sets, the lights, and the music (the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra for major productions). Hank Cubitt has toured the length of New Zealand several times with the company, and been to China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Italy as the touring wardrobe mistress — yes, mistress. “Master was actually mistress when I first joined — touring wardrobe mistress,” he says. “I was that for many years.” Mistress could also have been replaced with “caretaker” for the role includes caring for the costumes on the road. On tour, Cubitt always has a spray bottle of vodka to hand, the cheapest he can find. It’s a trick he stole from a Russian ballet company. Seeing vodka in their kit, he assumed it was for drinking — until he saw it sprayed on costumes. The alcohol sanitises smells and germs, and is especially useful for costumes which are too delicate to wash after each use.

When Cubitt joined the company in 2009 he already had impeccable garment construction skills from running his own menswear shop, House of Hank, on Wellington’s Willis St. Still, making costumes is different to fashion — the wearers need to move, and the fit is closer to the body. Cubitt learned from then head of wardrobe Andrew Pfeiffer, who “took me under his wing, which I am very grateful for. Unfortunately, he passed away a few years ago. I stayed on at the ballet and he went to heaven.”

Today Cubitt’s title is senior costumier, mostly working from “our home base”, the St James Theatre on Courtenay Place. As well as a “fantastic” workroom, the costume department also has a stockroom, a laundry, and dye and paint rooms, where they upkeep and create costumes. When the company first started performing at the theatre in the 1980s, there was a small creek that ran through the basement, the dressing rooms were infested with rats, and a Coca-Cola vending machine did double duty shoring up part of the stage.

The parlous state of the St James in the 80s is mirrored in the company’s history: funding and financial crises have come, gone and retuned cyclically. In 1981 the company was on the verge of bankruptcy, and 10 of its 28 dancers were let go. Currently the company is funded by its box office, grants, sponsorships, donations and bequests, and direct funding from the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. The RNZB’s most recent published annual report, for the year ending December 2021, shows the slender gap between their revenue ($13,512,000) and expenditure ($13,035,000). These are modest numbers, considering that top male All Blacks are reportedly paid $1 million a year, and there are currently 46 in the squad. The total expenditure of the RNZB wouldn’t nearly cover the All Blacks’ payroll. In 2018 the salary for an experienced senior dancer was $75,000 — about the same base starting salary as a Hurricanes player. It isn’t surprising, then, that for much of its history the company has searched for a permanent home, and occupied a string of inadequate spaces.

The St James Theatre was refurbished in 1997. The vending machine and rats left the building; its baroque façade, rococo auditorium, detailed plasterwork, gold paint and plush red velvet stayed. In 1998 the Wellington City Council gifted the St James as the home space for the RNZB — finally, a worthy home. In 2019, the company moved out in order for it to be earthquake strengthed. It wasn’t until this January that they were able to move back in. When he wakes up each morning, Cubitt looks forward to arriving at work. “It’s incredible to have the opportunity to build these dreams for people and then get it on stage. At the end of the day, that’s what we’re here for.”

“I couldn’t do my job unless it’s a whole team of Hanks,” says Grant Lord. “He is so wonderful, and there are so many people that make the show. Collaboration creates a sort of whānau around these shows.”

Grant Lord began her career as a stage manager at Centrepoint Theatre in Palmerston North. It was a small company, so the stage manager also made the props, helped with scenic painting and “things like that”. She then got an apprenticeship at Auckland’s Mercury Theatre, where she continued to design and make for shows. Today, Grant Lord is a “one stop shop” for production design. “I create an entire world,” she says.

FINALE

In 2015, that world was the enchanted woods of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This ballet unfolds over the course of a single night, in a fairy dell deep in the forest. It’s the story of the fairy world, and its mystical lovers, being disturbed by blundering human explorers. Grant Lord designed the sets, places where fairies live, work, and play, as a very particular kind of architecture — their structural forms looked like dew drops and mushrooms, mysterious and entangled with nature. Clytie Campbell was on stage as Hermia, a fairy who passionately rejects male authority figures in order to claim her own sovereignty in the realm of love. “It was beautiful,” she says of the set. “When I went on stage for the first time and saw the set around me — the bridges going up and across, the stairs that went up to the bridge — it was actually magical. And they were quite high. It’s a very cool set to be dancing on stage with. To have that around you, you really feel like you’re in that world.”

In rehearsals, the stage and elements of the yet-to-be-built set are taped out on the floor of the studio. Dancers are talked through the set, and shown images, but “you can never quite understand it till you get on there and see it”, says Campbell. During performances, “it really helps you get into the character, it’s the same thing as putting on costumes”.

Midsummer’s costumes were beautiful too. Grant Lord had explorers in fishing vests, gaiters and hats; and bejewelled fairies tufted with cobwebs and blossoms who held mushroom-like umbrellas. The characters these costumes capture are “beautiful roles that everyone really loves dancing”, says Campbell. Playing Hermia, she had “some fun with the antics — she’s not too nice and boring. It’s a lot of play”.

In 2017, a restaging of this production turned out to be Campbell’s last performance as a dancer with the company. She was offered the role of ballet master — one of three who train dancers, prepare them for productions and ensure the smooth running of rehearsals and productions. It is another role that was once “mistress”, but at the RNZB, “we’re all ballet masters now”. It seems a role that Campbell, with her ballet teacher mother, was destined to do. “Even when I was quite young, other dancers started saying ‘Oh gosh — she’s gonna be a ballet mistress one day.’ I don’t know if that put it in my head, but I realised that this is what I wanted to do.”

Though she occasionally does walk-on roles, like the queen in Cinderella last year, during performances you will most often find her amongst the audience, at the front in an aisle seat for a quick exit if necessary. She will be taking notes, watching for what can be improved, and what isn’t going quite right, so she can work with the dancers to fix it for the next show.

Grant Lord’s ethereal fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2015.

CURTAIN CALLS

Campbell won’t be the only familiar face in the audience. When she was on stage in Cinderella, Jon Trimmer was watching. “I loved Cinderella because it was so happy,” he says. Though he’s a regular in the ballet’s audience for performances in Wellington, Trimmer misses being in the company. “It was home,” he says.

While he marked his 80th birthday four years ago by taking a lead in Meeting Karpovsky — a play with ballet — at the Circa Theatre, these days he sticks to floor exercises, yoga, and painting in his and Jacqui’s cottage close to the beach in Paekākāriki. These activities are “more gentle than dancing”.

You might spot Kerry-Anne Gilberd, another regular, in the audience too. “It feels like you’re going to support your family. I kind of want to say to them, ‘Don’t be nervous, we will love you and we’re gonna love you no matter what.’ I wish they knew how much they are treasured, because it’s not glamorous at all. You don’t make a lot of money, and it’s very, very, hard work.” Gilberd is looking forward to this year’s season of Romeo and Juliet. Her favourite role was Juliet, and when she danced it in 1994 she decided it should be her last.

In a discipline like ballet, classic productions are mounted over and over, echoing through generations. Act II of Swan Lake was first danced by the company in its very first year. It was performed in the open air of Auckland’s Western Springs, where real swans flew, unchoreographed, onto the stage to join the ballerinas. Swan Lake appears in the history of the company’s programmes more than 20 times.

Campbell, who has been watching ballet “literally since I was born”, loves seeing the same stories retold. “A ballet that you’ve watched over and over, so many times, like Romeo and Juliet for instance, it’s the same but different. I think I fell in love with the music when I was about three years old.

“I thought it was amazing when I didn’t know what it was, and I still think it’s stunning. I’d watched the scenes when I was a child, and then danced them in productions of Romeo and Juliet over the United States, Europe, and then back here. I’ve seen numerous productions of it — it’s nice that little bits of the steps that stay in your head from different versions will always be there, but then to see or learn new steps for the same piece of music — it sort of layers.” Campbell was in her role of ballet master when her favourite production, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, was restaged in 2020 and 2021. Passing on her knowledge of it to new groups of dancers is something she has found extremely rewarding.

Similarly, Gilberd returned to ballet as a teacher and coach, and today says, “I love nurturing the talent, and passing on my love for the artform. A career in ballet can be very short, but some people go through their entire lives not finding their passion. I was so lucky.” Three years after retiring from performing, Gilberd was made a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit (MNZM) in 1997 for services to ballet. She feels blessed to have found the beauty of ballet. “The simple purity of ballet’s line and language. Ballet should be beautiful, and, when you leave, you should feel as if you’ve been taken to a magical land.”

It’s been 30 years since Gilberd was in her favourite place, “centre stage, with a beautiful costume and a live orchestra. That’s where I felt safest, and what I loved the most. When I was dancing, I forgot everything else.” Somewhere, in a dark, temperature-controlled room, there’s a tutu made to fit her body like a glove. Its silver sequins, now more than 100 years old, still shine.

Ballet master Clytie Campbell took a supporting role as the queen in Cinderella, 2022.

The Royal New Zealand Ballet is celebrating moving into its eighth decade with Romeo & Juliet (4 May–10 June), Lightscapes (27 July–12 August), and Hansel and Gretel (26 October–9 December). See rnzb.co.nz for details.

Gabi Lardies is North & South’s junior staff writer, a role supported by NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the May 2023 issue of North & South.