Follow Her Home

Tracing the tale of a little house – from Taupō landmark to Raglan family home – raises as many questions as it gives answers.

By Monica Evans

“Lovely little whare. I wonder what happened to it? Must be firewood by now.”

“I remember that place. It was right smack bang in the middle of HeuHeu St. Old lady always refused to sell.”

“Such a shame we haven’t kept hold of our history. Should be a crime.”

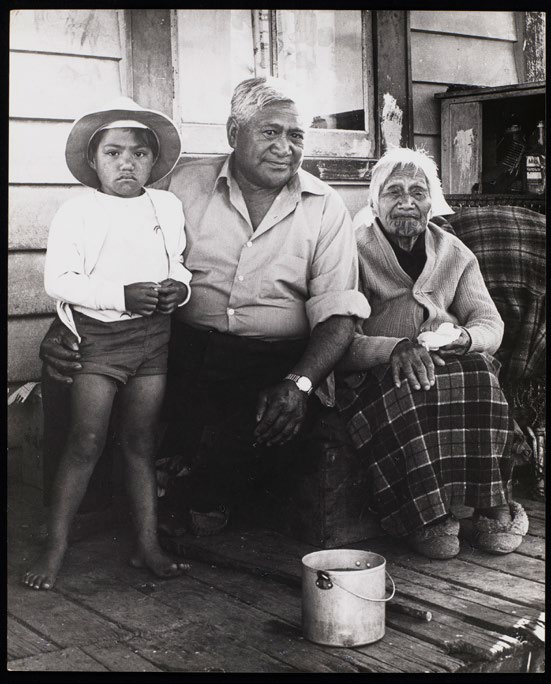

I’m chewing through the comments section under a black-and-white photo of three people on the porch of a tiny wooden house, which has been shared to a Taupō locals’ group on Facebook called “U know ur from taupo when…”. As I read, I feel the redness rising in my cheeks, the soles of my feet curling inwards: I know exactly what happened to that house. I’ve pried rotting planks off its porch, clambered up into its cupboard-like roofspace to sleep, left the sweaty handprints of labour on its pock-marked timber walls. Two hundred kilometres northwest of its original location, the house now sits, much-changed, in a wet green valley in Raglan – and I live in it.

If it weren’t for that photo, I’d never have learned the backstory of this place. It’d be just another quirky inheritance of the Raglan land that my partner and I bought with my sister’s family six years ago, passed on like the avocado tree and the dodgy plumbing for us to puzzle over, prune, and problem-solve as we saw fit.

A previous owner, Linda, had had visions of a communal lifestyle on the steep, south-facing property, and had arranged a collection of buildings on-site: a farmhouse, two identical kitset cabins from the 90s, and – for the cheapest rent of all – a 20-square-metre hut which was connected via a sheet of corrugated plastic roofing to a purple-and-green structure on poles that seemed to have been part of a long-immobilised housetruck.

The hut’s front step was worn into a deep arc by the constancy of feet. Inside, dark chocolate-toned timber, studded with rows of blackened nail-holes, lined the walls. Soot darkened the ceiling and burn marks decorated the floor. In the cocoon-like back room, a piece of frayed yellow cloth blocked the sparse sunlight that emanated from the glass panel in the door. Someone had written “love and light” on the window in fluoro-pink puff-paint.

Thanks to a poorly-attended auction – and loans from our mostly-Pākehā Boomer parents – we bid successfully for the land and its village of buildings and began working out how to make our home there. My sister’s family took the farmhouse, and my partner and I moved into one of the 90s cabins. But I was pregnant, and the hut exerted a kind of gravitational pull: we wanted to have our baby there. That first winter on the land, we hacked out space for a north-facing window, connected power and water, built benches, knocked down the single interior wall. I lay on my back in the muck and used my feet to propel my rounding body underneath the hut to stuff long rectangles of green insulation into the spaces between the joists. Doing the same for the walls, Manu found a penny from the 1950s that had been tucked in through a crack in the boards.

We tried to find out more about the tiny house’s provenance: Linda told us she’d found the place in a relocatable-buildings yard in Hamilton, but we didn’t manage to trace it back further – the old fulla who might’ve remembered had died the year before.

The photo that started the search: Rititia Irihei on the porch of the Taupo cottage with her son Winara and his granddaughter Waitapu, photographed by Marti Friedlander for 1972’s Moko.

Rititia Irihei, Tuwharetoa 1970 Taupō. EH McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust, 2002.

The penny drops, so to speak, four years later. My sister comes home fizzing from book club and holds an opened hardback to my face, jabbing her finger to the black-and-white photo inside.

The book is 1972’s Moko – a work on traditionally-tattooed kuia by historian Michael King and photographer Marti Friedlander. The image shows a white-haired woman with a tartan blanket on her lap and a moko kauae on her lips and chin, a kind-eyed man in a hat and a young boy. Behind them there’s a little house, cartoon-like in its proportions, as if a child had drawn it: triangle roof, colonial barred window, chimney, door. “That’s it,” I say, my heart beating faster with recognition and certainty. “That’s the hut.”

“Rititia Irihei. Tūwharetoa”, reads the caption: the woman’s name and iwi. Suddenly, the house’s past lives are Googleable. I search Rititia’s name, and find the same photo shared to numerous Facebook groups, with a treasure trove of memories underneath. I email the Taupō Museum and they leap on the case, email me fragments from all kinds of files: newspaper clippings, photos, paintings, jotted conversations with folks who remember the hut – and her.

The history begins to reconstruct itself. I learn that the hut was built around 1890 by an Irish shopkeeper called Tom Noble, on Tongariro St in the future town-centre of Taupō, which at that time was a small village dreaming big; a scattering of buildings spread out on an optimistically wide grid of dusty roads. The structure — that same 20 square metres that would later turn up in Raglan — was nailed together from thick slices of native rimu, felled in a forestry flurry before people realised they were running out of big trees too fast.

Sometime in the 1920s, the hut was loaded onto a trolley and dragged by horses to a quarter-acre section on nearby Te Heuheu St. Tom installed a tank to catch rainwater, an outhouse, and an even-smaller sleepout alongside. For many years, he ran a dairy out of the hut; the stories go that he was a kind-hearted, generous man who let the locals – both Māori and Pākehā – have accounts at his shop, and never turned them away if they couldn’t pay.

In his later years, Tom went blind. With his mother’s help, he managed well with his daily routines, guiding his way around the village by counting his steps. After she died, he hired a Tūwharetoa woman, Rititia, to be his housekeeper. Well, that’s one way the story got told: we know that Rititia stayed with him there until he died, and that somewhere along the line the records start referring to her as “Mrs Noble”.

The hut and the section it stood on belonged to Tom, but he wrote in his will that Rititia could reside there for the rest of her life. That ended up being a lot longer than most people anticipated: it is said she lived to be 114. The town grew up around her and the scraggly section became prime real estate. Property developers begged her to sell, but she always refused. Lots of Taupō locals remember her there, walking around town with the help of a stick taller than she was – which she also used to attract attention when she wanted service in the bank or grocery store – or sitting on her front porch, watching the world change around her.

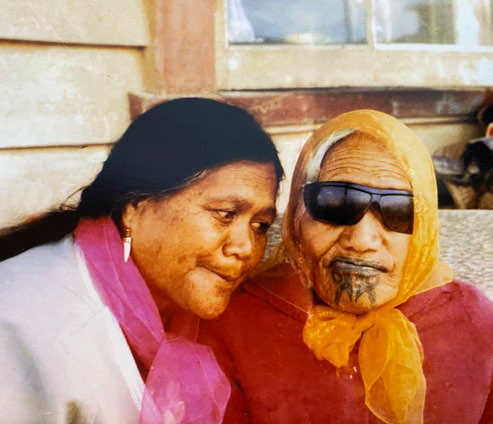

In September 1975, the New Zealand Herald ran the kind of article that only makes it to the national newspapers in small, parochial places. Headlined “Many Descendants at Party”, it described Rititia’s 114th birthday at a local marae with about 300 of her 400-plus descendants. She’s pictured in cool octagonal glasses and a woollen beanie, sitting next to her son Winara – the kind-eyed man from the Moko photo, and the only one of her children to outlive her. “Mrs Noble was at the meeting-house from 8 am to 5 pm on Saturday and had a firm handshake and a true Maori welcome for each of her descendants who came from near and far,” wrote the reporter. “At the end of the day, in spite of her remonstrances that she wanted to walk, she was carried to a car.”

The discovery comes at an awkward time. We’ve just ripped the side and front off the hut and transformed it into a much bigger, two-storey house.

For three years, we’d lived the tiny-house dream in that place: doing our dishes on the back deck, showering in a cast-iron tub pushed up against a rocky bank, and picking our way to the outdoor toilet across cold gravel in the darkness. (We also had a fancy coffee machine, fast Wi-Fi, and abundant hot water, so it wasn’t like we were really doing it tough). Visitors admired the simplicity – “It’s all you need, isn’t it?” – and then returned happily to their own, larger abodes. I twirled brass hook after brass hook into the nail holes on the walls, suspending all possible possessions above the precious few square metres of floorspace.

In 2020, with my belly round a second time and a toddler spilling chaos out of every carefully-packed corner, our hermit-crab shell had become decidedly too small. We set about making the hut into a more conventional-sized home: knocking the walls out to expand in two directions, adding another storey off one side. No-one realised quite how much of the original structure we would have to pull apart: with two of its walls stripped away, the thing resembled a doll’s house, kitchen shelves exposed to everyone who walked down the driveway. The framing spread out and upwards and I cringed, feeling the presumptuousness of taking up space: lifting beams and aligning cladding to claim segments of light and air. Meanwhile, my body continued its own expansion, unabashed.

We sanded, filled, and oiled the dim brown floor, which began to glow red and blonde. The burn marks became a wabi-sabi feature. The torn-off weatherboards reappeared as architraves, each revealing its own personality as it drank up the oil. We rearranged some of the interior cladding, and a board with a kids’ chalk scribble on it ended up where the tallest person couldn’t reach. In that frantic and expensive flurry, I wasn’t sure to what extent we were honouring or destroying this thing we’d loved so much. Were we doing her nails, or picking meat off her bones?

Rititia Irihei, Tuwharetoa 1970 Taupō. EH McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust, 2002. Photo: Marti Friedlander.

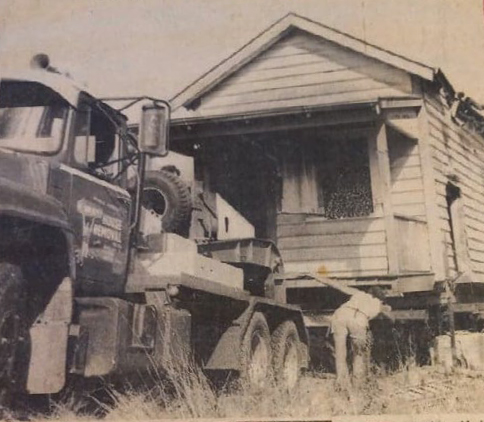

Rititia died in the autumn of 1976. As developers crowded in on the Heuheu St section, local doctor and history enthusiast Tangi Martin bought the hut for a bargain and shifted it – along with the water tank and a flax bush that grew alongside – to a plot of land just out of town, on the Waikato River near the Huka Falls. Parked up alongside other old buildings from all over Taupō, the hut spent the next 20 years as part of a staged settlement and tourist attraction called The Historic Huka Village. On a postcard of the “main street” from the early 1990s, I can just make out the roof-shape and dark red corner-pole of the porch.

The enterprise was memorable, but not very lucrative: in 1995, Tangi sold it, and the new owners got rid of the old buildings and remade the place as an upscale resort. Rititia’s descendants fundraised to move the hut to her land block – a sliver of lakefront in Acacia Bay, on Taupō’s western edge. She’d gained the title for it in 1931, but the Government had amalgamated it in 1975 into a bigger piece of land, to be governed by a trust. The trustees at the time didn’t want the house set up there permanently in case it encouraged squatters. It sat on the side of Acacia Bay Rd for a while, chocked up on skids. Then, one night, it disappeared.

This part of the story is uncertain, but it seems like the council wanted the hut gone from the roadside, so the trust got it uplifted on the quiet by a local removal company, and it took up its next position in their relocation yard. Some of Rititia’s descendants spotted it there and went to check it out: “but the mauri was gone, so we grabbed some of the photos on the walls, and left,” one told me. Another said they’d hoped to keep it there in storage, but lacked the funds to pay. Soon after, the removal company went bust, and the hut was shifted northwards to another yard in Hamilton, where Linda found it, bought it, and brought it to Raglan.

Paula, one of Rititia’s great-grandchildren, remembers as a teenager in the early 70s going with her dad to visit Rititia in the hut. She recalls newspapers tacked to its walls as a modest attempt at insulation, and her father speaking with Rititia in Māori, while Paula marvelled at the papery, translucent skin on her hands. “Now, I wish I’d asked her more questions,” she told me on the phone from Melbourne, after another relative put me in touch. “But, you know, I was too young to realise the significance of it at the time.”

Paula’s done a lot of research about her kuia’s life. She tells me that Rititia was born in the village of Tāpapa, a hundred kilometres to the north of Taupō, to a Tūwharetoa mother and a Scottish soldier-surveyor-interpreter father, but that she was brought up by her maternal grandmother in Acacia Bay. As a teen, she moved back to Tāpapa, where she received her moko at the age of 16: a painful but prestigious process that required a day of carving into the skin with chisels and filling the bleeding gaps with ink. Soon after, she was married by arrangement to a local, older Māori man, with whom she had six children. When her husband died, tradition dictated that she should then marry his brother. Instead, she and her younger children caught the logging train south to the settlement of Mokai and continued back to the lake on foot: a mother duck guiding her ducklings back to their pond. They lived for a while in a tent in Acacia Bay, until her path collided with Tom’s – and with the hut.

Paula’s research is important to her as something to hand on to her own children, but it’s also very practical: she’s been working on her whānau’s application to partition Rititia’s land off the larger block, so that descendants can make more use of it. After many years and much effort, she’s recently found out that the partition is going to go through. To Paula, the reappearance of the hut is a beacon: a message, as if from the kuia herself, that all is well.

Rititia on her porch with daughter Polly Diamond (née Hamiora). Photo: Gail Rakatau.

A newspaper clipping from 1977 shows the house being moved from Heuheu St to Huka Historic Village, just outside Taupō. Clipping courtesy of Monica Evans.

The next time I see the Moko photo, it’s right there on Rititia’s land on the lakefront. I’ve journeyed down to Taupō with my family to track some of the hut’s travels. Our first destination, the spot where the hut used to stand in the town centre, doesn’t hold much resonance: it’s a chain-store bakery beside a busy arcade, backed by a concreted alleyway where courier drivers honk and hurtle past as I try to pinpoint the exact spot from a grainy aerial photograph on my phone.

Later, though, we follow directions from neighbours to locate the land block: a sunny scrap of grass and trees backed by stretches of eucalyptus and wilding pine, which feels quite anomalous given the upscale lakefront development on either side. There’s a chain across the driveway, and I’m ready to turn and leave, but my partner is bolder: “Let’s just see if there’s anyone there.” We circle past a clump of trees and see a guy sitting on a foldout camping chair in the sunshine, in tracksuit shorts and a singlet. Our footsteps startle him and he bristles, eyebrows lifted and lips set hard in a sceptical “can I help you?” I feel intrusive and wildly out-of-context, and I’m ready to bolt – but instead I blurt out our story and he grins and pulls up that photo from the Moko book, which he’s saved in a folder titled “Whānau” on his phone.

This guy is another of Rititia’s descendants, and he’s caretaking while the family sorts out their settlement; wants to make sure whānau can always return there to camp. He shows us her watertank, half-covered by a stand of bamboo: when the hut was uplifted from the roadside, it seems the tank was allowed to stay. The interaction feels tender, awkward, profound. The hut is with us now. What do you think about that? I want to ask him, but don’t.

Driving home, I fantasise about turning back the clock, undoing the renovations, lifting the hut from its foundations and sending it back to the lake, to follow and honour its former owner’s stubborn, resolute journeys home. In the next breath, I’m relieved I didn’t know its story until it was too late: the new renovations – concrete, steel beams, chopped-up boards and cladding – make such a move impossible. After all, I self-reason, it’s not like the little place would go far towards sheltering her descendants, now in their hundreds, or righting the racial disparities of the housing crisis. But wouldn’t it have felt so right to send it back to Rititia’s land: hand the ragged, well-travelled treasure back for future generations? Or is that just the classic white-saviour fantasy – to efface my unease about the whole bloody system with one emblematic, heroic gesture like that? Are there better ways for me to wield my own luck in this land?

We get home, light the fire, and draw the house around us like a cosy cloak. I notice how it’s already imprinted with the marks of our inhabitancy, our layer in the fossil record. The front step is carved deeper still, as our footsteps add to the groove; the pristine pine walls in the new kids’ bedroom bear their first ballpoint pen engravings, a line of all the letters my four-year-old can remember. We’ve scratched up the shiny floors shifting ladders and chairs. The place is no museum piece now, but its form and materials are riddled with story. And for us, for now, it’s home.

Monica Evans is a freelance writer living in Raglan with her whānau.

This story appeared in the January 2023 issue of North & South.