Exploring the edge

For 60 years, the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California has attracted spiritual seekers, social changemakers and psychedelic explorers. But the birthplace of the human potential movement also created cult leaders like Bert Potter. Now its focus is on Indigenous reconciliation.

By Anke Richter

There can only be one place in the world where you find yourself naked in sulphurous water and sea breeze, touching knees in the dark with a New York Times bestselling wellness author, a start-up entrepreneur, a psychiatrist from Harvard and a PhD candidate who researches tantric sex. The first thing I hear when I slide in next to her in the concrete pond is a reference to her “inner child”. My arrival at the hot pools doesn’t stop the confessional flow around me. They don’t do small talk at Esalen — people tend to be as open as the starry sky above us.

Coming here means going to the edge. Literally. The stylish open-air baths where clothing is optional sit only metres above the crashing surf under a steep cliff face of California’s west coast. They are an iconic feature of the seminar centre in Big Sur, three hours drive south of San Francisco. I’m here for a “self-guided exploration” that includes morning yoga classes and daily sessions called “Resting for Resilience” or “Making Space for the Sacred”. The pools are free to use for all guests around the clock, but a trademark 75-minute Esalen massage would add another US$230 to the already steep price tag. I’m resistant to making space for that yet.

Stunningly located just below the Pacific Coast Highway on over 11 hectares, with weathered buildings and a small organic farm, the Esalen Institute is a retreat centre as well as a hothouse for personal development. In its 60 years, it has birthed new-age gurus, hosted Silicon Valley think tanks, dabbled in drug experiments and facilitated secret peace meetings between CIA and KGB agents, since known as “hot-tub diplomacy”. It has been spoofed in Hollywood movies like Serial, Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice and Inherent Vice and has re-emerged as a stronghold of the psychedelics renaissance, with Michael Pollan, author of the bestselling book and Netflix series How to Change Your Mind, a prominent faculty member of the Esalen Institute. The latest rumour circulating this enclave — false but fitting its mythos — is that it has been bought by Elon Musk.

Countless celebrities, artists and intellectuals have soaked in the springs, wandered among the redwood trees and sat in the wood-clad lodge overlooking the ocean. Folk festivals and marriages have taken place here. Even a famous fictional character had a dip and a deep dive. In the final episode of the hit series Mad Men, Don Draper leaves the advertising rat race for the mystical mecca of counterculture. After he reluctantly joins an encounter therapy group for his soul-searching, Draper ends up in tears. Maybe he got in touch with his inner child.

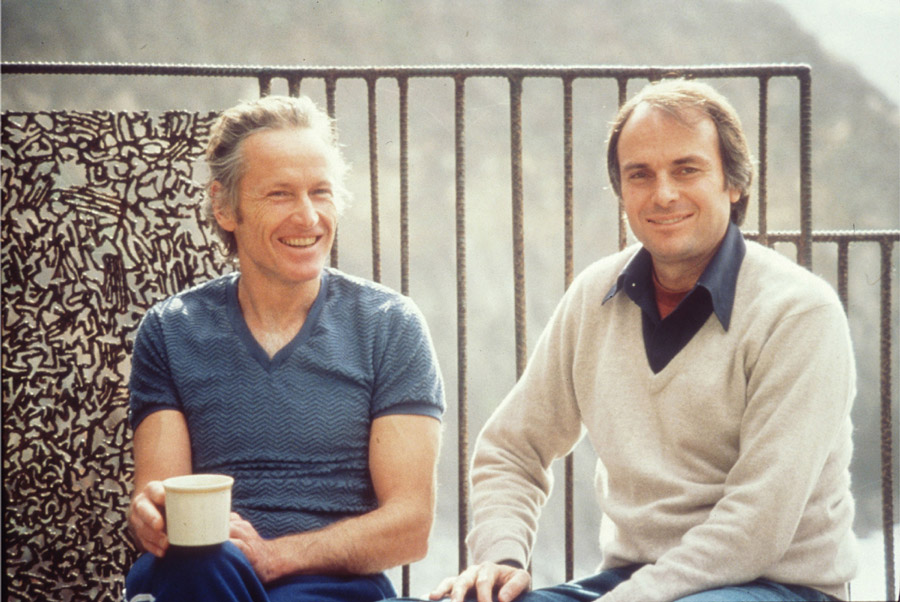

Esalen founders and college friends Dick Price, left, and Mike Murphy, who saw the potential in “human potential”. Photo: Courtesy Esalen Institute and Esalen Center for Theory & Research.

TRUTHS AND THERAPIES

“A lot of things happen here that are hard to explain,” JJ Jeffries tells our group of a dozen self- explorers in the welcoming circle above the lodge. He has a wide smile and a grey ponytail and has been part of the staff for 20 years, since the days when everyone at Esalen was into Gestalt therapy. Staff had daily “check-ins” and weekly “processes”.

A lot has changed since then. Ten years ago, the holistic hub where travelling hippies once camped on the driveway had a management restructure to attract a more upmarket clientele. That didn’t go down well. Esalen’s 50th anniversary was overshadowed by protests over the direction of the privately-owned non-profit. Staff and supporters stood outside the lodge in a “grieving circle” every day, claiming that it was going corporate and selling its soul. An “Esaleaks” website emerged while Esalen started holding exclusive weekends for Google, Apple and Facebook executives.

Alongside the palace revolution and financial struggles, the cliff-hanging enterprise had its share of natural disasters in a precarious environment: mudslides, fires and an El Niño storm where the baths ended up in the ocean. Then the pandemic hit, another fire and evacuation. The centre managed to reopen, with Covid testing and mandatory vaccination passes on arrival. Gazebo Park, a kindergarten built in 1978 for residents’ children (currently 45 of Esalen’s 100 employees live on site) and based around Gestalt principles like self-reliance is now a nature-based “forest school” open to local pre-schoolers.

Jeffries is one of the few Gestalt teachers left. He describes his vocation as “an awareness practice that is really good about noticing hidden patterns and beliefs”, then encourages us to get up for a dance. “Come on, move your hips — you spent a lot of money coming here!” He laughs and turns on the music. “To change your life, you have to change how you think, and move.”

Bodywork like rolfing and Feldenkrais, encounter therapy and Gestalt therapy kicked off at Esalen in the 1960s and became hallmarks of the human potential movement. The term “human potential” was coined by Brave New World author Aldous Huxley and taken on by Esalen’s founders Dick Price and Mike Murphy, both idealistic Stanford graduates with a dream to change the world, starting at the core of each human being.

The former had endured a horrific episode in a mental hospital; the latter became a golfing yogi after a stint in India. His family owned the modest Big Sur Hot Springs with a motel and a bar that were transformed by Price and Murphy into something more utopian. They gathered an eclectic in-group of resident psychologists and visionaries, who pioneered everything wild and wacky that promised personal growth, from Eastern philosophies to mescalin and LSD — legal at the time. Not all endeavours were enlightening. Some psychonauts ended up with psychosis. Some killed themselves.

The encounter groups were radical too: Everything raw, emotional and repressed was to be let out between participants, the more physically unrestrained the better. Risk — and sex — was part of the adventure. In one heated group incident, a man was thrown through a closed window.

Indian new-age guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, later known as Osho, copied these pressure cooker methods at his ashram in Pune in the 1970s and took them to extremes. Besides sexual liberation, the confrontations led to workshop carnage like broken bones, mental collapse and even rape. In 2017, I visited the padded cellar rooms at Pune where those monstrosities once played out.

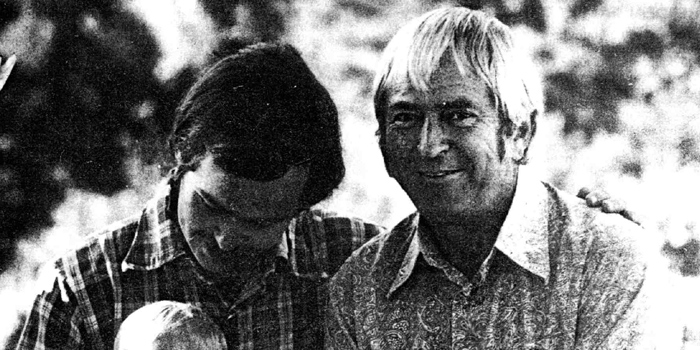

Centrepoint founder Bert Potter first encountered Esalen in Playboy and would use Gestalt therapy in his enterprises. Photo: Courtesy Esalen Institute and Esalen Center for Theory & Research.

Another infamous cult leader closer to home got his first bearings from Esalen: Bert Potter, who would go on to start Centrepoint Community after his US visit. He later visited the ashram in Pune. In India, he got his idea to start a money-making, tax-free religious enterprise and call himself “God”. Potter went to jail in 1992 for sexually abusing children and manufacturing drugs. (Twenty years later, the late Potter still hovered like a ghost over the research I did for my book about the disastrous aftermath of Centrepoint, which left hundreds of people broken and traumatised.)

A Playboy article about Esalen first caught Potter’s attention in the early 1970s. On his return from California, while still running a pest-control business, he set up the Shoreline Trust in Campbells Bay. Gestalt therapy was on offer at Shoreline, with its focus on internal processing and personal responsibility, with the aim of improving relationships. Not just his followers embraced it, but many local counsellors at the time. John Potter, who served prison time for two counts of indecent assault on underage girls, mentioned Esalen in his father’s eulogy in 2012. He said Bert had “practised being assertive” there and read books by Esalen regulars like Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg.

Potter’s Albany community became the antipodean appendix of the human potential movement — badly inflamed and doomed to burst. The Gestalt “hot seat”, where you sit in the middle screaming out your pain while banging a cushion, or receiving everyone’s brutally honest feedback about you, became a staple of Centrepoint workshops. Like German-born psychotherapist Fritz Perls, the father of Gestalt, Potter also had no intention of stopping anyone who came to him expressing thoughts of suicide.

Gestalt founder and groper Fritz Perls, later described as a “misanthropic septuagenarian in a jumpsuit”. Photo: Courtesy Esalen Institute and Esalen Center for Theory & Research.

While Potter’s atrocious acts can’t be blamed on Esalen, “careers, even cults would be made and broken here”, wrote Walter Truett Anderson in The Upstart Spring, which covers the first two decades of the institute.

I find Anderson’s fascinating book at the boutique gift shop among resort wear, bath salts and healthy snacks. The cassava crisps on the shelf are innocuously called “Cult Crackers”.

Anderson describes Perls, “an institution within the institute”, as a misanthropic septuagenarian in a jumpsuit who compulsively groped women’s genitals in the hot tub and slept with his patients.

Perls wouldn’t be the last predator in residence. Much later, but still before #MeToo, an older male yoga teacher from New Zealand allegedly fondled a young American student’s naked breasts and tried kissing her in the bath, which she told me about. “You can easily trick yourself there into thinking you’re the guru,” a wary Kiwi had told me. He was inappropriately touched by a think-tank leader in the changing room while on a course in 2011 and claims the complaint wasn’t followed up, unlike the yoga teacher incident. “They buy their own theatre and don’t recognize the pitfalls.”

I’m also aware of questionable Esalen superstars of the 70s, such as self-help lecturer Werner Erhard, “king of the brain snatchers”, who started est (Erhard Seminars Training). Labelled as a cult and a grift, est was the precursor to Landmark, another emporium with a hard sell that still runs large group awareness trainings (LGAT). Cult experts like Janja Lalich, founder of the Lalich Center on Cults and Coercion, claim that LGATs can make participants more susceptible to undue influence. “Your brain chemistry reacts to the intensity, and you attribute the highs you experience to the leader,” she says. Lalich is wary of the “pop psychology, scream therapy and all the attack therapy” which is also popular in Lifespring, another transformational coaching programme that has been blamed for driving people into suicide and breakdowns. “All cults use high-arousal techniques, whether it’s music or chanting or speaking in tongues.”

“SAY HI TO YOUR SOUL”

Arriving at Esalen with all this cult baggage on my mind doesn’t lessen the appeal of the place though. Although fringe by mainstream standards, the current programme and biweekly “Voices of Esalen” podcast leans more towards social justice, diversity and progressive thinking than crystal-waving woo- woo. The organisation has a female CEO now, and women in senior leadership roles. According to its communications team, the institute sees itself “as metaphoric midwives and doulas of cutting-edge exploration”, creating “a safe haven for big thinkers and wild dreamers”. Mike Murphy, who’s still a grey eminence in the background and charismatic as ever at 92, doesn’t overshadow the place he co-created — he has long retired to Marin County.

Esalen’s mantra since its early days of zen meditation is “the religion of no-religion”: to remind people of who they really are, not to put hooks into them — nobody captures the flag, they say, but you hop on life’s cosmic bus when you leave, questing onward. At the end of the first yoga session, instead of mumbling “namaste”, we’re encouraged to “bow to the greatest teacher: yourself ” — and to the Esselen people, the native American stewards of the coastal waters and the land that the campus resides upon. Petals are sprinkled on the floor outside the room. A raccoon ruffles through a bin.

My first impressions are more wonderful than weird, starting with the charming exterior: a quaint cottage stocked with art materials, a sofa swing among trees, a Buddha statue plastered with sentimental notes, and delicious buffet-style meals. Someone has arranged pebbles on a rock that read: “Say hi to your soul”.

Then there are the guests themselves, the majority of them women. There’s Shanna, a mother of three who works in tech and is “on a healing journey”, including psychedelic therapy. She came here on her therapist’s recommendation. “I’m realising I cannot access my feelings,” she tells me while we soak up the sun on the deck, then thanks me for my “spontaneous gift of listening”.

There’s an older couple — she has insomnia, he fights an addiction — who attend the “Heart Essence of Recovery” evening class, a 12-step programme. There’s wealthy Jim from Santa Barbara who loves the tranquillity here as much as the freedom of expression. Looking up from his journal, he says he’s come for a reset. “Everyone is seeking something.”

Another group of guests are health workers who suffered burn-out during the pandemic. They’re restoring themselves in a more affordable month-long Live Extended Education Program (LEEP). Students sleep in dorms and help with cooking and cleaning while they learn about relaxation or mindfulness under the tutelage of scholars, in this case wellness author Lissa Rankin, whom I met in the bath.

Given the controversial history of Esalen, it’s reassuring to hear that on the first day of her course, the medical doctor with a spiritual leaning spent hours to “cult proof ” her group, as she tells me: Rankin acknowledged the built-in power differential and encouraged students to give her critical feedback, to hold her accountable for any mistakes, and to set strong boundaries for themselves. The handbook that Esalen hands out nowadays to its “seminarians”, as it calls them, starts with a page about consent, in typical human-potential lingo: “Consent is freeing everyone to fully participate in this life we live together.”

Wellington psychotherapist Rachel Davies says the techniques she learned at Esalen “felt revolutionary”. Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Davies.

Wellington pyschotherapist Rachel Davies says her time at Esalen taught her techniques that were not then available in Aotearoa. Davies lived in at Esalen from 2010 to 2013 and has many happy memories of her

time there.

“I was worried at first it would be a bit of a ‘Gestalt cult’, but the place wasn’t kooky, just cutting edge. I worked in the kitchen and made everyone pavlovas, and I did workshops all the time. I laughed and cried and never wanted to leave.

“When the [staff] protest in 2012 happened, I stood outside in the circle every day. I learned so many modalities there, like NVC (non-violent communication), meditation, mindful self-compassion and hypnotherapy.

“The community lived by the values it taught — that you speak from your own experience and don’t take things out on others. I got to bring all these treasures back and use what I learned every day in my work as a bioenergetic psychotherapist-in-training. Alexander Lowen, who created bioenergetics, was a big influence at Esalen, and so was the bold and innovative work of Wilhelm Reich. There was nowhere I could have done that in New Zealand at the time. It felt revolutionary.” Davies has maintained Esalen connections: she will bring Esalen writing teacher and performer Ann Randolph to New Zealand for two retreats from late January.

Davies in the kitchen during her three-year stay. Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Davies.

Apart from frank conversations in the hot tub that span from microdosing to past lives, the highlight of my week is the 5Rhythms dance. The two-hour long experience — ecstatic, sweaty, exhilarating — is led in a packed dome by a rockstar teacher, expat Kiwi Douglas Drummond. The gentle giant in a black t-shirt that says “Boys should cry” is the director for healing arts. After an international career in hospitality, he married the daughter of Esalen’s massage matriarch Peggy Horan and moved to Big Sur for his dream job.

The 41-year-old, of Ngāi Tahu descent, represents a new generation that isn’t isolated in a magical time bubble. Over lunch the next day, Drummond admits that the halcyon days of the past were “probably inappropriate and out of line, especially the patriarchal ways men treated women”. Esalen being so far away from everything has added to its magic, he says, and while it’s still on many Americans’ bucket lists, it’s also insulated and needed to become more culturally diverse to stay relevant. “I think you can cherry-pick the best of the past while also adjusting to the realities of today.”

Kiwi Esalen director Douglas Drummond (Ngai Tahu) is working on reconciliation with the local Esselen tribe. Photo: Anke Richter.

His current focus has been on reconciliation work with the Esselen tribe of Monterey: spending time with them and inviting them to co-facilitate workshops where he integrates 5Rhythms with their own traditions. “Esalen has had to really take notice of its appropriation of its namesake,” he says. “We’re sitting on some of the most sacred tribal lands in central California, so there is a reverence on a spiritual level for me.” Supporting the Indigenous people and funnelling “conscious investments” their way is what he’s most passionate about, besides raising his family and spending time exploring the coastal wilderness. “This is an exciting moment in Esalen’s history.”

Drummond points at the guests who are eating outside, deep in conversations, some reading books. Given the amount some are willing to spend for this experience, he says, resources could flow back to the tribe. “I’m more interested in exploring that than just risking the further perpetuation of white wellness culture.”

The overpriced massage I turned down upon check- in seems more justified now — and more desirable by the minute after watching the shiny happy people who traipse back from their sessions, oily and glowing. Or is it just the hype that this place creates, which lifts every pleasant experience to a “transformation”? I will never find out. The last massage slot for the week is long gone.

Lyttelton-based writer Anke Richter is the author of Cult Trip: Inside the World of Coercion and Control (HarperCollins, 2022). She has written extensively on Centrepoint for North & South.

This story appeared in the February 2023 issue of North & South.