The Flames of Our Shame

The fatal fire at Wellington’s Loafers Lodge has reinforced calls for greater scrutiny of boarding houses, places occupied by those with nowhere else to go.

By Max Rashbrooke

In the days and weeks since the Loafers Lodge fire, which killed five residents of a central Wellington boarding house, the blackened soot marks on the building’s facade have – in some eyes – come to symbolise a much wider disfigurement. As the Green Party co-leader James Shaw asked, on the day of the tragedy, “What kind of country are we, that those people have so few options in life but to live in substandard accommodation with a reasonable chance of lethality?”

Before the fire, though, these were not issues politicians had wanted to confront. In the financial world, people often talk about the shadow banking sector: the poorly regulated assortment of small lenders that operate in the penumbra of their bigger, more conventional counterparts. But other sectors of the economy have their own shadows, and none more so than housing. Now, in the ghastly light shed by the Loafers Lodge fire, a motley assortment of little-scrutinised homes – night shelters, campgrounds, decrepit private rentals, makeshift dwellings and, of course, boarding houses – have briefly been brought back into full view.

Even in this shadowy line-up, boarding houses are notably hard to pin down. The law defines them as dwellings with more than six rooms, each of which is rented separately and, in theory, for more than four weeks. But this covers all kinds of places. Some are simply run-down, two-storied Victorian villas, every available room up for rent. Others, like Loafers Lodge, are converted office buildings. Some are backpackers.

I first encountered boarding houses a decade ago, when I stayed undercover in a place called Malcolm’s, in central Wellington, while researching a book on economic disparities. The rooms at Malcolm’s were damp and mouldy, the rain poured in through windows that didn’t close properly, and 14 people shared just one working shower with a cracked concrete floor. No hot water in the hand- basins, no toilet paper in the toilets, no fridge, no washing machine: it was, by any objective standard, dreadful housing, yet its residents were paying $150 a week, in cash, often without a bond, a tenancy agreement, or indeed paperwork of any kind.

Some residents – typically older, male, and alcoholic – had tolerated these conditions for a decade or more, having, as one put it, “nowhere else to go”. Conventional private landlords didn’t want them as tenants. And although their poverty and their health problems would have made them “ideal candidates for long-term social housing”, in the words of University of Otago public-health lecturer Clare Aspinall, such housing was – then as now – in short supply.

The regulation of boarding-house tenancies was minimal. Anyone staying for fewer than 28 days had essentially no legal protections. Even after four weeks, they could be evicted immediately if the landlord believed they were about to cause “serious” damage to the property or threaten someone’s life. While this might seem reasonable, the precarious nature of tenants’ lives meant such provisions were wide open to abuse, and revenge evictions – landlords ejecting people who made complaints – were not unknown. Unsurprisingly, few tenants dared speak up. As one former resident of Malcolm’s, Pete Bryant, told me: “They accept it [their situation] because they don’t know any different.” The only thing in tenants’ favour was that they had to give just 48 hours’ notice before moving out.

The buildings themselves faced even fewer regulations, beyond the need to get an annual fire-safety certificate. As I discovered when I reported Malcolm’s to the local council, it couldn’t be prosecuted under the Building Act because it wasn’t deemed actively dangerous or “unsanitary”.

Owing to its age, any leaks or similar faults were considered maintenance issues, not structural problems of the kind covered by the Act. Since, in any case, the local council had no ability to launch its own inspections, and few tenants were likely to lodge complaints, the owner of Malcolm’s had little reason to fear the law.

Some residents – typically older, male, and alcoholic – had tolerated these conditions for a decade or more, having, as one put it, “nowhere else to go”.

Even the regulations that did exist were not always enforced or especially meaningful. Aspinall, who wrote her master’s thesis on boarding houses, recalls visiting one that was notionally compliant with the law. “There was a fire safety certificate on the wall – and then a broken banister right next to it, and a broken electrical socket. How can you say something is safe when you can’t even walk down the stairs safely? It’s ticking the boxes, but it isn’t actually meeting basic standards of what you would consider to be safe.”

Tributes to those killed in the Loafers Lodge fire in a bus stop on Adelaide Road. Photo: Max Rashbrooke

Boarding houses have long been part of New Zealand life. But whereas they were, in the post-war era, a rough but functional form of accommodation for single working men, they have – with the end of full unemployment and the post-1980s rise in hardship – come to cater for a much poorer, more vulnerable and more marginalised community. Loafers Lodge, for instance, housed migrant nurses, ‘501’ deportees from Australia, people serving community sentences, ex-prisoners, beneficiaries and the elderly. At one stage it had been used for emergency housing. Social agencies often placed people there: in a city with the country’s highest rents, a chronic shortage of homes and 765 families on the waitlist for state housing, there were few other options.

Scenes from boarding houses around New Zealand. Photo: Stuff.

Experts believe that because boarding-house tenants are often poor and marginalised, stronger regulation is urgently needed; and because they are often poor and marginalised, it remains weak. Conditions that would not be tolerated elsewhere persist because they are invisible to the mainstream. “I think there’s still quite a lot of New Zealanders that don’t know what goes on [in boarding houses],” Aspinall says.

Politicians, though, cannot claim ignorance. At some point in 2009, Aspinall found herself driving two Opposition Labour MPs – including the future finance minister, Grant Robertson – around Wellington, pointing out boarding houses to them. They even stopped and talked to residents at Malcolm’s. By the time of my 2012 exposé of that establishment, the Department of Building and Housing was clearly aware of the problem. Officials told me they were focused on “education” campaigns to inform tenants of their rights; tougher laws were “not a top priority”. Yet when my boarding-house exposé was followed by a 2014 Stuff investigation into Auckland’s worst establishments, Housing Minister Nick Smith was forced to admit that parts of the sector were “unfit to house your dog”.

Around the same time, MPs on Parliament’s Social Services select committee concluded a long-running inquiry into boarding houses that amounted to a catalogue of state failure. The government did not even know how many existed, beyond a rough estimate of 500-550, of which fewer than one in 10 were believed to have sprinklers installed. Consequently there was no reliable data on how many broke the law (though the committee acknowledged some clearly did) or were in substandard condition (though witnesses to the inquiry testified that many were). More upmarket establishments, offering long-stay accommodation to contract workers, vied with “low-end” places marked by “dangerous and unsanitary” conditions. “While some boarding houses are managed well,” the report concluded, “others fall short of the most basic standards that could be expected.” Councils carried out “little enforcement” of a patchwork of provisions scattered across multiple acts.

Some of the sector’s problems, the committee found, stemmed from 1990s-era deregulation. Before the Building Act was passed in 1991, the law had required councils to register and licence boarding houses and ensure they were “safe and secure”. Premises were inspected at least annually. But the committee found such provisions “were likely to have been repealed under the Building Act as ‘unnecessary controls and costs from the regulatory system’.”

In the end, and despite the evidence presented to them, the committee’s National MPs recommended only cosmetic changes such as enhanced information-sharing (although they did suggest that “where necessary” standards might be raised). Some boarding houses were, by their own minister’s testimony, unfit even for dogs; and yet no urgent reforms were needed. Only the committee’s opposition members – Labour, Green and New Zealand First MPs – demanded tougher action, including a return to compulsory licensing.

Other warnings were soon sounded. Later that year, a study by Victoria University fire engineer Geoff Thomas raised what turned out to be prescient concerns about the lack of sprinklers in the shadow housing sector. “Low- quality, unsprinklered hotel and backpacker accommodation,” Thomas noted, “are of particular concern as they provide the highest fire fatality risk.” In 2015, Otago University master’s student Tim Anderson found that regulation was “fragmented, weak and dated”, citing clear evidence of boarding houses breaching health and safety laws. One community worker told him: “To be honest I’m waiting for a major fire [in which] there’s a lot of people killed.”

Everyone, it seems, was playing a waiting game. Despite Nick Smith’s strong language in 2014, the only concrete achievements he could name three years later, when questioned in Parliament, were to have required boarding houses to install smoke alarms, declare their level of insulation, and meet tighter “electrical safety requirements”. A new “enforcement regime” was also supposed to be in place, although this seems to have had little effect. In June 2017, Newshub’s The Nation show found “horrific conditions” in South Auckland boarding houses. In the worst instance, missing windowpanes were “leaving the filthy pest-infested house freezing cold”, the show reported, adding: “The house smells like excrement because there is no working toilet.”

The Labour Party’s housing spokesperson, Phil Twyford, described the situation as an emergency, promising to eliminate the “rat-infested dumps” the programme had revealed. A Labour government, he said, would bring in a warrant of fitness that would set tough minimum standards for safety, warmth and dryness – and “urgently” clean out “slum” boarding houses – within three months of that year’s election.

This does not, however, seem to have eventuated. There is still no national register, although the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) does hold over 3000 bonds from 821 boarding houses, of which 29 per cent are in Auckland. (Since very short-term tenancies do not have to have bonds lodged, this is probably a slight undercount.) Brett Wilson, the agency’s national manager of tenancy compliance and investigations, told North & South that inspectors “proactively” visit boarding houses to check they are complying with the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA) and the new healthy-homes standards, which require all dwellings to have insulation, fixed heating, drainage, draught stopping and ventilation.

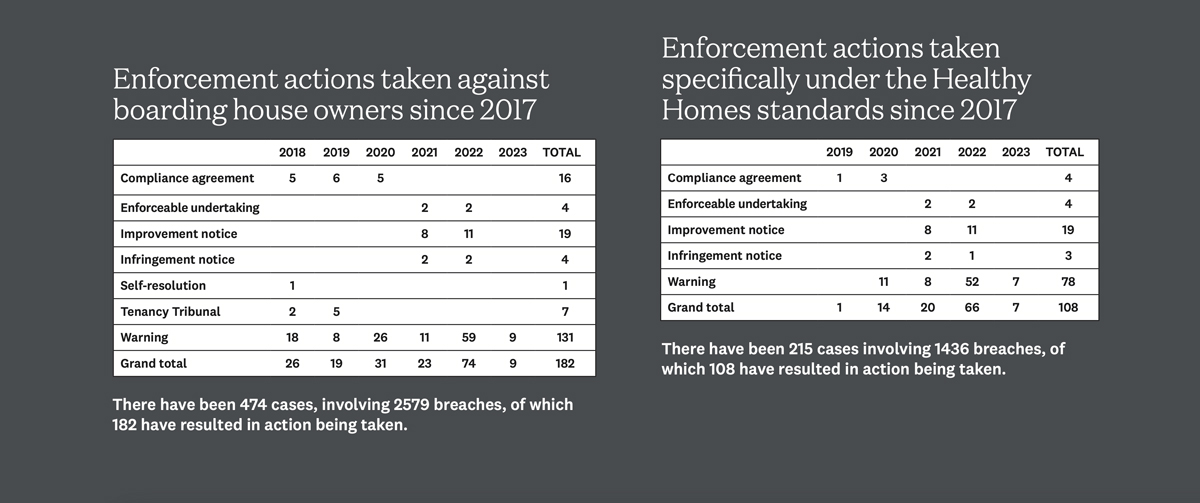

This scrutiny seems to be increasing: MBIE took 74 “enforcement actions” against boarding houses in 2022, up from 26 in 2018. The majority, however, were warnings regarding the healthy- homes standards, and MBIE spends a significant amount of time trying to “educate” landlords before prosecuting them. Decisions against landlords represent a relatively small proportion of the identified breaches, although MBIE has won all 23 of the Tenancy Tribunal applications it has brought against landlords.

The “patchwork” of regulations, as identified by the 2014 select committee inquiry, continues. As well as meeting the tenancy and healthy homes requirements, boarding houses must have a building warrant of fitness (WoF) certifying their compliance with fire and other safety regulations. But Aspinall’s experience of hazardous homes sporting compliance certificates – and the fact that Loafers Lodge had an up-to-date WoF – raises questions about how effective such measures are.

Indeed the overarching system for regulating boarding houses looks messy. The initial certification of WoFs is part-privatised, carried out by commercial firms. Councils are supposed to double-check firms’ work, and MBIE triple-checks whether councils are doing enough double-checking.

In some cases, they clearly are not. Last year Wellington City Council was, according to RNZ, reprimanded by MBIE for inspecting only a tiny number of commercial buildings annually. It had not checked Loafers Lodge since 2018, when it found “blockages at fire exits and smoke-stop doors wedged open, and a non-compliant card-access system”, something that might have been expected to prompt more regular re-inspection. The council has now vowed to do better – although, as Mayor Tory Whanau points out, it has limited resources, and had been neglecting checks on old buildings partly to keep up with the demand to inspect and approve new ones.

Other local authorities have done slightly better: Auckland Council, for instance, has a proactive compliance team that inspects boarding houses for fire safety, tenancy law breaches and cleanliness, and claims to have obtained a Tenancy Tribunal order for over $200,000 against one property management firm. Even so, each year it checks perhaps one-tenth of the city’s boarding houses.

By the time of the Loafers Lodge fire, boarding houses had long been displaced from the headlines by Rotorua’s emergency motels and the wider crisis of homelessness. And in policy-making circles, a certain inertia has prevailed: experts describe a dispiriting cycle in which government officials ask for advice, meet to discuss the problem, and then sit on their hands. Aspinall says officials typically proffer two excuses for inaction, the first of which is that only a small number of boarding houses are substandard. But, as she points out, it’s hard to know how any such assertion can be made, given the lack of systematic data and the abundance of first-hand testimony of appalling conditions.

The other recurring excuse is the supposed cost of regulation. “There’s always this argument that we will have to pass these costs onto tenants, so it will make housing more expensive,” Aspinall says. “But what I’m seeing is that costs go up regardless.” Rents, in her view, are set not by landlords’ outgoings but by tenants’ incomes: “There is a price point they [tenants] can afford, and landlords know it.”

The government’s current reliance on boarding houses for emergency accommodation further diminishes the likelihood of tougher laws: although more taxpayer funds than ever are going into such places, the state’s desire to rock the boat is even more limited than usual. (Indeed it has accepted emergency housing providers’ request to be exempted from the RTA.) Someone who knows this first-hand is 41-year-old Wellingtonian Iosua Clarke, currently a resident of Halswell Lodge, a boarding house that doubles as emergency accommodation. Before that he was in another emergency housing place, on Dixon St, and before that he had been serving a 20-month prison sentence.

He has previously visited Loafers Lodge – “that was a rough place, man it was rough” – and says, of his own accommodation, “I really want to get out of there.” It’s not the premises themselves, which are “good, living-wise”, but the environment created by so many people battling personal problems. “They put all the struggle people in there, and people that just came out of jail, people from the street, gang members and that … It’s not a good environment.”

Scene from a boarding house. Photo: Stuff

Although a private rental might be pricier still, Halswell Lodge isn’t cheap: while his arrangements with Work and Income are complex, Clarke thinks he pays around $200 a week and the state another $100. His problem, as someone recently released from prison and battling alcoholism, is that other housing is hard to find. “A lot of landlords don’t want to know,” he says; meanwhile, the waiting list for state homes remains lengthy.

The long-term consequences of the Loafers Lodge tragedy remains unclear. A coroner’s inquest will examine the specific circumstances of the fire. Former residents have alleged ongoing safety breaches and a dysfunctional fire-alarm system, claims denied by the building’s managers. Prime Minister Chris Hipkins has also announced a review of the building regulations for “higher-density accommodation”. Some observers, however, want wider reform.

The Salvation Army’s Ronji Tanielu believes one of the many arms of government must bear the responsibility for cleaning up boarding houses. “Nobody really wants to take ownership of these issues,” he told Stuff last month. Aspinall says a compulsory register is an obvious first step, alongside a licensing system that would apply tough quality standards and weed out the worst performers. “Basically, over time, we shouldn’t have places like that. We just have to say, ‘No, it isn’t acceptable.’ That’s progress, isn’t it?” And if local councils are to proactively enforce such a system, rather than just waiting for complaints from tenants, they will need to be funded to do so. Auckland councillor Chris Darby has previously described the current arrangement as “very much a case of pass the buck without the budget”.

Such reforms would be in line with overseas practice: British local councils, for instance, have clear powers to close down substandard boarding houses, while various Australian states run registration and licensing systems. Aspinall also believes that if older buildings are to be used as accommodation, they must be brought up to modern fire and safety standards rather than being allowed to meet those of their era, as is currently the case.

Shutting down some boarding houses would, of course, risk worsening homelessness. Back in 2012, Wellington City councillor Stephanie Cook told me that although tougher regulation was needed, the sad reality was that it would lead to boarding-house landlords quitting – “and the government will be left to deal with it”. Given the continuing shortage of affordable housing, her warning still holds true.

But for the advocates of reform, this only reinforces the need to build more homes, especially in the social sector. As various observers have pointed out down the years, boarding-house landlords are accommodating people who – owing to their multiple personal struggles – should be looked after by the state, ideally in long-term social housing with a full suite of health services provided on-site. The alternative is that vulnerable people continue living in conditions no-one should ever have to experience, Aspinall says. “It’s heart-breaking.”

By Max Rashbrooke.

This story appeared in the July 2023 issue of North & South.