Back on track: The new Golden Age of rail

Long-distance rail travel is in for a revival in New Zealand — eventually. And you don’t have to be a nostalgia buff, trainspotter or climate-action protester to see why.

By Theo Macdonald

Photo by Shutterstock

We’ve heard a lot about the future of transport.

Flying cars, autonomous vehicles, and colossal lengths of pneumatic tubing are just three of the sci-fi solutions fantasised about in blockbuster television shows and Silicon Valley.

But although these technological marvels stimulate endless speculation, a popular counter-narrative responds that such transport innovations do not address the urgent issues confronting us right now. Variations on the single- occupant automobile, such as electric cars, do little to diminish the environmental damage of endless roading. Deluxe solutions to traffic congestion, such as autonomous air taxis, are impractical to scale. As novelist William Gibson famously observed, “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.”

Attitudes are changing. In Aotearoa, transit experts, environmentalists, concerned citizens and government officials are looking back to the beginnings of the industrial revolution for an answer to our transport woes. They’re assessing an expanding populace (2.3 million Aucklanders by 2048), interpreting the available data and beginning to seriously consider a return to mass interregional transit — a return to railways.

In 1863, New Zealand’s first public railway connected Christchurch to Ferrymead.

Before then, travel was mostly by sea or river, due to the nation’s dense forests and mountainous terrain, and the resistance of North Island Māori to selling their land to rail projects.

The following year, the short-lived Southland Province built a wooden line linking Invercargill

to Makarewa. The rails swelled in the rain and sparked into flames during summer. Three years later, a 27-kilometre iron rail joined Invercargill and Bluff but bankrupted the province.

In 1870, in the final stages of the New Zealand Wars, colonial treasurer Julius Vogel unveiled a 10-year plan to expand the existing railways to a comprehensive network totalling 1600 kilometres. Narrow gauge rail was set as the national standard and earlier rails were relaid accordingly, the Bluff line in a single day.

As in other British colonies, the railways in New Zealand bobbed along in the currents of imperialism and land theft. In Canada, the bicoastal Canadian Pacific Railway was completed to send Eastern troops to quell indigenous resistance in Western Saskatchewan. Similarly, Julius Vogel’s ambitions involved expanding Crown influence amongst Māori in the North Island interior. The government’s newfound ability to construct a national rail network extended from post-war land confiscations.

The New Zealand Railways Department (NZR) was established in 1880, by which time the expanded network carried three million passengers annually. One notable traveller was novelist and raconteur Mark Twain, who wrote, “Nothing that goes on

wheels can be more comfortable, more satisfactory, than the New Zealand trains… When you add the constant presence of charming scenery and the nearly constant absence of dust — well, if one is not content then, he ought to get out and walk.”

Although passenger numbers grew in the early 20th century, the rail network was conceived as a freight system and had a significant role in transporting timber, coal, livestock and mail. In 1920, NZR recorded 28 million riders, but in the ensuing decade, cars and buses chipped away at passenger use. From the 50s, passenger rail struggled to compete with the convenience and efficiency of private vehicles and air travel. Between the 50s and 90s, annual long-distance passenger numbers slumped to 391,000.

New Zealand Railways was corporatised in 1982. A lack of investment in passenger services — a policy of “managed decline” — meant ramshackle carriages and unreliable services, therefore fewer customers.

In the early 2000s, passenger rail services to Rotorua, Tauranga, Napier, Dunedin and Invercargill ceased. The Auckland-Wellington overnight train was discontinued in 2004.

Today, passenger rail is predominantly for commuters in Auckland and Wellington. KiwiRail also runs three tourist-oriented scenic lines: the Northern Explorer, the Coastal Explorer and the TranzAlpine. The two remaining interregional services for regular customers are the Capital Connection, between Palmerston North and Wellington, and Te Huia, introduced in 2021 to link Auckland and Hamilton.

A 1963 postage stamp of the steam locomotives Pilgrim and DG Locomotive, celebrating 100 years of railways in New Zealand.

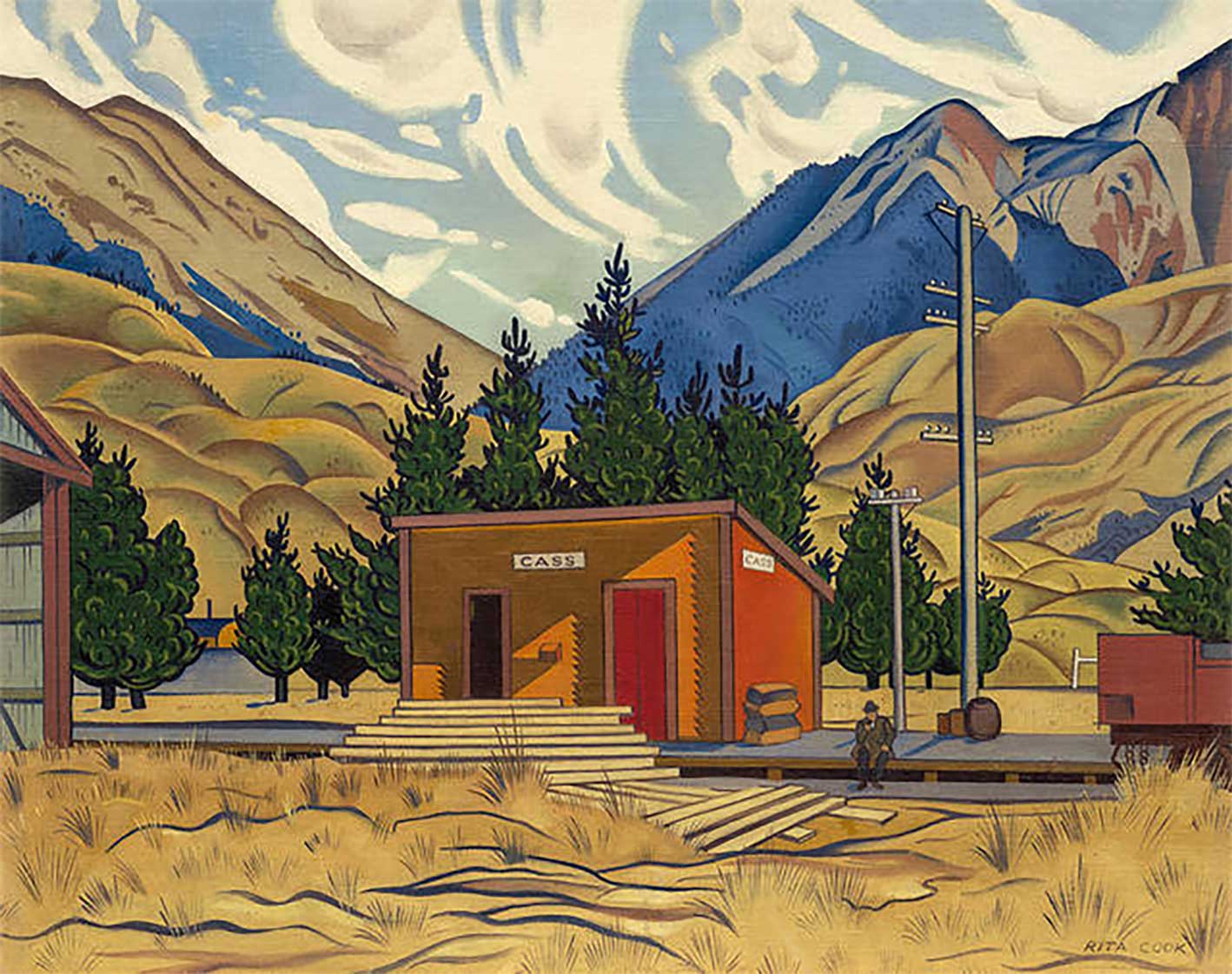

A romantic image of the New Zealand railways underpins

today’s debates on reviving interregional passenger rail. The railways emblematise Kiwi ingenuity — the Raurimu Spiral — and bridging the rural-urban divide. For Parisians, the City of Light’s modern era is inseparable from Monet’s paintings of the Gare Saint-Lazare. In New Zealand, the same stands true for Cass, Rita Angus’s railway station painting.

But the case for passenger rail is more than romantic. Save Our Trains, Making Rail Work

and Restore Passenger Rail are advocacy groups that have emerged in recent years to rouse the government to reinvest in the national rail network.

Their arguments cohere around three themes. First, rail is equitable. It services those who can’t drive or can’t afford to drive, including seniors and people with disabilities. Second, interregional rail connects New Zealand’s rural communities to metropolitan centres, with economic benefits including greater employment opportunities and increased spending in rural towns. Third, and perhaps most convincingly, railways have substantial environmental advantages compared to cars and air travel. A train journey emits approximately one-sixth of the greenhouse gases of an equivalent plane trip. A six-carriage electric train takes an estimated 625 cars off the road.

In Europe and North America, the “no-fly movement” has accelerated since the 2010s. This year, France banned short-haul flights that can be completed in less than two-and-a-half hours on a train. Flygskam is Swedish for “flight shame”, and the phrase has a foil in tågskryt, meaning “train pride”. Yet there are limited options for New Zealanders afflicted with flygskam — who want to enjoy tågskryt — despite the government’s commitment to net zero emissions by 2050.

Of course, arguments against interregional passenger rail abound. Sceptics bring up New Zealand’s hilly terrain, earthquake risk and narrow-gauge rail. Making Rail Work has been disputing such criticisms through a crisp social- media campaign. Mountains? The present rail network already navigates this terrain, and any necessary developments will expand from existing rail corridors. Earthquakes? Japan successfully runs over 30,000 kilometres of railways, and in past disasters, trains have returned to service before roads. Narrow gauge? New Zealand trains already run to a peak of 110 km/h, and overseas, rolling stock runs on narrow gauge tracks up to 160 km/h.

Ultimately, it’s a problem of finances. In a vacuum, public transport loses money; when

public assets have a profit motive, it makes things complicated. For example, Wellington’s commuter- rail service funding is divided into roughly equal thirds, paid by customers, Wellington City Council, and Waka Kotahi. Some economic conservatives believe these subsidies are unsustainable. Public transport advocates counter that public transport is an investment rather than a subsidy; that this investment is about more than just economic, environmental and accessibility benefits. It is about a vision for New Zealand moving forward.

Rita Angus’s Cass (1936), collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū (left), and the station building as a train passes in modern times (right).

Photos: Shutterstock

How do we value rural New Zealand?

Should we rely on single-occupancy vehicles (New Zealand has the fourth-highest rate of car ownership in the world)? Are we sincere about diminishing our environmental impacts? What sort of a nation will remain for future generations?

These questions, and many more, were under investigation at the Future is Rail Conference, held in May at Wellington’s Public Trust Hall, a restored national treasure that architect and academic Guy Marriage has called “politics and legal documentation turned to stone”. I spoke to Marriage outside the conference. He’s more interested in metropolitan rail proposals than interregional transport, though he fondly recalls catching the night train from Auckland for skiing weekends in his youth.

The conference brings together the transport sector and government, with a smattering of community groups. It is a banquet of bald spots, nice shoes and loud jackets. Very Wellington.

A dry congregation, but the romance of the railways chugs along nonetheless. We enter with Bob Dylan wailing about a “slow train comin’ up around the bend”. Speakers quote Janet Frame, Johnny Cash and Michael Joseph Savage. When it comes time to settle, the ring of a conductor’s bell interrupts the chit-chat, followed by, “All aboard!”

The challenge of the day is to reach a consensus on the state of passenger rail in New Zealand, and work out what needs to happen from here; to turn abstract discussions toward concrete strategy.

Northcote MP Shanan Halbert, chair of the Transport and Infrastructure Select Committee, delivers the day’s first keynote address, a slick celebration of the Labour government’s investments in rail, including, since 2019, $8.6 billion toward replacing tracks, building new culverts and bridges, and upgrading turnouts. Halbert earns vigorous applause with a clarion call to “reframe rail from an alternative to a primary option”.

It is awkward timing for Halbert and Green MP Julie Anne Genter because the conference ever-so-slightly precedes the release of the select committee’s report on the inquiry into the future of interregional passenger rail, which received roughly 1700 submissions. A sea of hands approves Genter’s question, “Who here made a submission?” Because Halbert and Genter can only discuss their conclusions once the report is finalised, both presentations were light on concrete detail.

The presence of elected officials — including National MP Chris Bishop and local councillors from throughout the country — lends an additional tension, the uncertainty of pitching travel plans with a track switch on the horizon.

Despite National’s historic opposition to railway investment, public-transport advisor Michael

van Drogenbroek was encouraged by Bishop’s expressed interest in investing in railways where he perceives investment as economically viable, such as in the Golden Triangle of Auckland, Hamilton and Tauranga. Bishop’s panel with Flygskam is Swedish for “flight shame”, and the phrase has a foil in tågskryt, meaning “train pride”.

Genter deteriorates into truculent potshots, but he comments midway, “I grew up taking the train. I’m a believer in rail when it makes sense.”

The conference feasts on slogans. Auckland One Rail’s Magda Robertson: “Public transport is an essential service.” Transdev New Zealand’s Peter Lensink: “Let’s call our passengers customers.” KiwiRail’s Peter Reidy (an Upper Hutt boy): “My grandfather was a chief porter for New Zealand Railways for 40 years.”

Linking up the Golden Triangle is almost a consensus. Von Drogenbroek’s presentation

“Why Passenger Rail?” is a plan for connecting the country from north to south. Van Drogenbroek is a fierce advocate for rail, with experience as director of railway planning for Etihad Rail in the United Arab Emirates, which constructed 1200 kilometres of rail in a decade. He declares, “You need to be bold, you need to be brave, you need a purpose.” His priorities here are connecting the Golden Triangle and the lower North Island — Masterton, Wellington, Palmerston North, Whanganui — with fast, frequent passenger rail. From there, he proposes connecting Auckland to Wellington and Picton to Christchurch, then linking up the central South Island and beyond.

Other themes are the need for multi-modal planning — trains that feed cycle lanes, buses

that feed walkways — and the necessity of interregional cooperation. Darren Davis from transport consultancy MRCagney draws attention to how public transport systems follow regional boundaries, unlike the nationally integrated state highways, commenting, “Which way the water flows should not determine transport access.”

After each presentation, the panellists answer a slew of questions delving into yield pricing, funding allocation, and a complex proposal to fix an obtuse problem in East Auckland systems management. “It’s terrific to be specific” and these technical discussions are the point of the conference, but the unrelenting specificity eventually becomes exhausting.

Flygskam is Swedish for “flight shame”, and the phrase has a foil in tågskryt, meaning “train pride”.

A necessary break comes in three speeches by senior prefects from Ruapehu College and Taumarunui High School. Corbin O’Shannessey, Taumaranui High School Head Boy, says, “Rural communities may be small, but we have voices and we will be heard.” For O’Shannessey, his fellow students and Dunedin City Councillor Jim O’Malley (the sole South Island representative), passenger rail is a matter of existential significance.

The day ends with conference chair Roger Blakeley asking, “Where do we go from here?” The crowd agrees passenger rail is essential infrastructure, that a multi-modal approach is necessary, that rail can bridge the rural-urban divide, and that focusing on metro services underserves rural communities.

The challenges include a car and aviation bias, finding the proper public-private funding arrangement, negotiating regional borders, and track electrification. Large parts of the system must be restored, especially in the South Island. And although the government may change, rail needs long-term investment.

Hurt people hurt people. Do train people train people?

On this drizzly afternoon, in an underlit alcove at a dingy University of Auckland study room, I’m about to find out. Steam rises from two lime green paper cups. I’m at an orientation session by the controversial climate-activist organisation Restore Passenger Rail (RPR), here to get the view on the issue from outside the first class carriage.

RPR made headlines last October, mere weeks after forming, by blocking tunnels and highways throughout New Zealand, forcing road closures and delaying traffic for hours. Whether glued to State Highway 1, or abseiling down the side of the Mount Victoria tunnel, RPR’s mustard-coloured banner now signifies the interrupted morning commute. When I mention them to a colleague, he says that he understands why they care, but that such protests are “no way to win hearts and minds”. If Save Our Trains and Making Rail Work are concerned citizens, patient and reasonable, RPR is an edgy younger sibling; the skunk at the garden party.

Four of the six around the table are RPR members. Two of the four — all women — are in their early 20s; the other two are grandmothers. I ask a young member if she knew the university students would be on holiday when they announced the meeting, titled “Climate Crisis and Civil Resistance”. She laughs self-deprecatingly and acknowledges it could’ve been better timed. RPR is holding meetings throughout Auckland all week. I don’t get a sense whether the others were better attended.

Despite the name, this group is more about climate activism than public transport advocacy. Members perceive passenger rail as a more feasible way to reduce emissions than agitating for broad- stroke government regulations. According to their research, 75 per cent of New Zealanders support passenger rail linking cities and towns from Northland to Invercargill. So RPR has two simple proposals: restore the national train system to how it was in the year 2000, and make public transport free. But as the Future Is Rail Conference made apparent, the simplicity of these proposals is dubious.

The strategy makes sense when explained, though it doesn’t diminish any initial confusion prompted by a group called Restore Passenger Rail speaking exclusively about global warming.

RPR’s methods follow those of prominent UK activists Just Stop Oil, who notoriously threw tomato soup on (the glass protecting) a Van Gogh Sunflowers. This internationally detested protest action happened the same week RPR left Wellington motorists impotently honking. Both groups are part of the international environmentalist network, A22, whose members use peaceful civil resistance to protest lagging government progress on urgent environmental issues.

An abseiling protester from Restore Passenger Rail positions a banner at the mouth of Wellington’s Mt Victoria Tunnel.

Prime Minister Chris Hipkins called RPR “irresponsible and idiotic”; Wellington Mayor Tory Whanau remarked, “this group have gone too far”; Former transport minister Michael Woods, who met with the group last December, considers their approach “counterproductive”. Like Just Stop Oil, RPR members have been charged with non- violent criminal offences, for actions they argue are warranted by the severity of the climate crisis. They probably have a point. Or at minimum, a point of view.

The woman I’m speaking to moved to New Zealand from London, where she was involved in similar organisations. Her family encouraged her to move to New Zealand, where she has citizenship, and break with climate activism before it spoiled future prospects. She enrolled in carpentry training. However, the climate crisis continued to loom large in her imagination, so she dropped out and joined RPR.

She first became involved in protest at the age of 18, when a flatmate invited a climate protester to stay for the week. He woke each morning at 6am to blockade a local highway. He’d be released from jail in the afternoon, come home to sleep, and do it all again, like a nine-to-five job. In her retelling, before this encounter she had acted like the climate crisis was taking place in the pages of a novel, a problem that ceased to exist when she closed the pages.

The other young woman at the table is a nursing student exhausted from an all-night shift at Auckland Hospital. She is in tears as she talks about her family in Sri Lanka, where climate change drives a growing hunger crisis; predicted sea level rise will render 11 million Sri Lankans homeless.

RPR rejects business-as-usual attitudes. It contends that fighting the climate crisis requires interrupting the status quo, of which the daily commute is a rigid feature, and that members’ attention-grabbing activities push the needle of acceptability toward government response. One of the members shares that they have heard from Save Our Trains that RPR’s motorway disruptions tend to prompt an uptick in interest in Save Our Trains.

It is worth mentioning that the protests are clearly planned, the protesters rehearsing all eventualities to diminish risk to themselves or the public. Claims these actions risk injury seem to be ill-informed or disingenuous.

Rita Angus’s Cass (1936), collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū (left), and the station building as a train passes in modern times (right).

It benefits both sides of this argument to observe that news coverage of the protests gives little space to the organisation’s demands and plenty of attention to aggravated motorists.

The New Zealand Herald’s reporting on RPR’s Transmission Gully blockade frames a member of the public who hijacked a protest van to get around the activists as a “man on a mission”; a noble hero protesting the protesters.

As they mentioned their experiences with Extinction Rebellion and other protest groups, I sensed these women are tired of generic sloganeering. “Stop Climate Change” is agreeable but hard to action. “Restore Passenger Rail” couldn’t be more explicit.

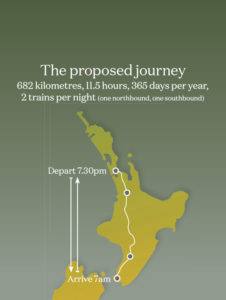

Presentations at the Future is Rail Conference stretch from thorny policy to offbeat spiel — the loopiest of the latter an idea to approach British supermarket giant Tesco to subsidise the Tauranga- Auckland link. One intriguing proposal came from Greg Pollock, an independent consultant with experience at Transdev and Metlink. Pollock’s pitch is a night train running daily between Auckland and Wellington — Britomart to Lambton Quay, and vice versa. It’s named ZZZERO, as in “zero emissions” and “catching some Zs”. Each 11-hour trip would emit under 3 per cent of the greenhouse gases of an equivalent-distance flight.

Pollock’s enthusiasm is impressive. An ideal night-train journey runs between eight and 12 hours, he says. To his thinking, the 11-hour trip on the North Island Main Trunk line is perfect. Enabling convenient nationwide interregional passenger rail will require infrastructure upgrades, new rolling stock and operation costs. Pollock has put forward ZZZERO because it doesn’t need that investment. The infrastructure already exists.

He describes the ZZZERO experience: “You finish work at five, go home for dinner with the family, head to the railway station and jump on the train around eight. On board, you have dessert, maybe a wine, perhaps watch a movie, then put your PJs on and sleep. The next morning you wake up in the middle of the CBD in a different city. You’re still getting where you want to go, but unlike on a blistering red- eye flight, you haven’t burned all that carbon, you haven’t had to get up so early, and you arrive at your appointments fresh from the on-board shower.”

At the conference, Waka Kotahi’s Deborah Hume declared, “Let’s not get distracted. If you are going in the direction of interregional rail, don’t muddy your proposal by trying to do 50 things.” I ask Pollock if he saw her statement as an invitation to ZZZEERO. “Absolutely. If we want to do a good job of this, we need clear-eyed commercial thinking about the customer problem we’re trying to solve and solve that one problem well.”

There’s a more profound mindset behind ZZZERO, too, a vision of taking our time, reducing our footprint on the world and perhaps just enjoying ourselves every so often. “People might choose to fly one way and train the other, but the thing I like about a night train is that it gives us a choice but also, in some ways, requires us to slow down a bit. In New Zealand, people are making different choices. Young people do not own cars, are keen on low-emission travel choices, and use public transport more than ever before. We’ve got to keep investing in that.”

Thomas Nash, a Green-affiliated councillor on the Greater Wellington Regional Council and chair of the council transport committee, comes to public transport advocacy from a background in the peace and disarmament movements. He believes Greg Pollock is the perfect person to deliver a night train, because he’s commercially minded with a lot of experience. “He’s not an idealist. He’s practical and outcome-oriented.”

Nash continues, “You have to set out what you want to see, make a plan, and find allies and funding partnerships. The Wellington strategic rail plan doesn’t self-censor about what we need to get passenger rail humming. It doesn’t shy away from cost or time. If we want a turn-up-and-go timetable, we need long term investment, and the best starting point is to paint a compelling picture.” Whether discussing demilitarisation or domestic railways, Nash believes mobilising the public requires setting out a positive vision rather than just criticising. Over the phone, he acknowledges the shift from warfare to public transport could seem like a weird juxtaposition, saying, “I returned to New Zealand in 2017 after a long time overseas, exhausted from spending so much time working in a field involving a lot of human suffering. I wanted to focus on advancing positive work, a bit more daily life for people in New Zealand, so I put my attention toward things like regional parks, restoring native forests and wetlands, and public transport.”

Greg Pollock’s proposal

One thing is clear: interregional passenger rail is making a return. The public, government and industry agree that it simply makes sense — in certain situations. That last bit is the wrinkle. The form our replenished passenger rail network will take depends on how the industry can package it economically. By 2050, will a passenger be able to affordably and efficiently travel from Cape Reinga to Bluff on electric railways? Probably not. But we can anticipate connections between the Golden Triangle, lower North Island, and the Auckland-to- Christchurch spine of the nation.

How quickly this happens will depend, as ever, on political will, along with public demand for the environmental and social benefits rail can deliver. It may well seem a Dylanesque “slow train” of change, but you don’t have to be the kind of person who goes to rail conferences to realise it’s definitely on its way.

Theo Macdonald is North & South’s junior staff writer, a role supported by NZ on Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.

This story appeared in the August 2023 issue of North & South.