Solar eclipse: Our renewable power struggle

Millions of panels could soon be erected across thousands of hectares of the country as an unprecedented solar-farm boom begins. It’s part of efforts to more than double the country’s power generation by 2050. What do we stand to gain, and what might we lose?

By George Driver

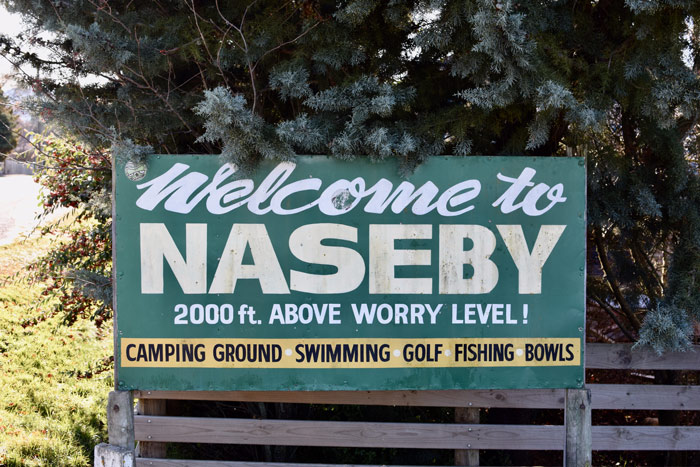

It’s a place known for its ice, if it’s known at all. Naseby, population 123, advertises itself as 2000 feet above worry level, but the former gold-mining settlement in Central Otago is also below freezing level for much of the year. When I visit at midday in June, the frost fills in the shadows cast by the pine trees surrounding the town. Naseby’s main attraction is the Southern Hemisphere’s first Olympic-standard indoor curling rink.

But about five minutes out of town, down an unsealed dead-end road leading to a timber yard and the tussock-clad Ida Range, is something more novel. Beside paddocks of grazing merinos are a series of large half-pipe structures, supported by a framework of steel beams. It looks a bit like a skatepark designed by Gustave Eiffel.

The half-pipes are actually radar dishes that track space junk. The facility, built in 2019, can monitor about 250,000 tiny pieces of space debris, some as small as 2cm, to help prevent calamitous collisions with satellites. In 2021, it was one of the first sensors to detect a Russian “space missile” test, when it picked up debris from a satellite the Russians had destroyed.

Naseby’s attraction for the space industry is its exceptionally clear atmosphere. Down the road at Lauder, a NIWA facility has been tracing the depletion of the ozone layer and other atmospheric gases since the 1950s, aided by what its scientists call the cleanest air on Earth.

Photo: George Driver

Now, that clear air is attracting a new industry. In the paddocks surrounding the space radar, about 80,000 photovoltaic panels will soon be installed, each tracking the sun’s path across the sky and transforming its rays into enough electricity to power about 9000 homes.

An Australian company, Solar Bay Energy, was granted a non-notified resource consent to build the 50 megawatt (MW) solar farm on the 54.5 hectare site in February. If it’s built, it would be about 25 times the size of the country’s current largest solar farm. Neither the landowner nor Solar Bay would comment on exactly what it would build and when. However, the construction of such farms is something we’re all likely to become much more familiar with.

In the last couple of years there has been a boom in announcements of large-scale solar farms around New Zealand, in what has been called “a gold rush moment for the renewable power industry”.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) estimates a thousand megawatts of solar-generation capacity has gained resource consent recently, which would amount to about 10 per cent of the country’s power generation capacity. But power-grid operator Transpower says there are almost 15 gigawatts (GW), or 15,000MW, of solar projects in the pipeline. That’s more than all of the country’s current power generation combined.

The solar farm consented in Naseby is a relative minnow. The largest consented so far, near Taupō, is 400MW, with 900,000 solar panels on a 1022 hectare dairy farm. Based on the scale of this proposal, 15GW of solar projects would amount to 33,750,000 solar panels over 38,325 hectares of land — an area larger than Egmont National Park — with around 10,000 hectares directly covered by solar panels.

It’s just one facet of a renewable-power generation boom that will transform the country over the next three decades, as we shift from powering the country on fossil fuels, to renewable energy.

Advocates say large-scale generation projects will enable our decarbonisation in the fastest and cheapest way possible. Sceptics say these “Think Big” solutions have an unacceptable environmental cost.

What happens next will affect everyone. Impacts will range from changes to the views from some people’s windows, to the price paid to switch on the lights — to whether there’ll be enough power to switch them on at all.

Charging ahead

We don’t often think about where our power comes from, but some of us think about it more than most.

When I look out the window of my home in Clyde I can see the 60-metre concrete wall of the Clyde Dam. At about 5pm, I can look down at the Clutha River and see the ripples on its surface intensify into swooshing whirlpools, as people get home from work, switch on the lights and the heat pump, and more water courses through the dam’s four 116MW turbines. In the middle of the night in spring, when the power from the dam is not required, its four spillways roar like storm surf on the coast.

For those more removed from the ebbs and flows of the country’s power supply, Transpower’s website shows exactly where the country’s electricity is coming from at any hour of the day.

At 10am on a Tuesday in June, 5645MW of electricity was coursing through the network to just about every household in the country. Ninety per cent of it was coming from renewable sources. The hydro lakes were full and providing 78 per cent; the North Island geothermal plants provided 16 per cent. But the wind must have dropped — wind farms were providing only about 3 per cent. Gas power stations, mostly in Taranaki, generated another 8 per cent, while the coal in the furnaces at Huntly power station topped up the network with 79MW, or 1.4 per cent of the total.

It’s a delicate balance. This mix changes throughout the day and throughout the year, based on the rise and fall of the lakes, the wind and demand.

New Zealand is in a fortunate position. In an average year, around 84 per cent of our electricity is from renewable sources — one of the highest proportions in the world. Our network has been ranked ninth best in the world based on the equity, security and sustainability of the system.

In an average year, around 84 per cent of our electricity is from renewable sources — one of the highest proportions in the world.

But the system is about to drastically change. Our emissions-reduction targets rely on moving transport and industry from fossil fuels to electricity by 2050. All of that power will need to be renewable if the country is to meet its net-zero target.

It requires the electricity network to expand on an unprecedented scale. In 2020, Transpower estimated the country would need to more than double our power generating capacity by 2050, increasing from 9.2GW to 21.8GW.

Demand for power, meanwhile, is expected to rise by 68 per cent. More than half (56 per cent) of this will come from electrifying our transport fleet and almost a quarter will come from electrifying process heat — things like the boilers used to dry milk powder that now mostly rely on coal.

Breaking that down, it amounts to 466MW of new electricity generation built every year, for 27 years. To put that into perspective, the Clyde Dam, the country’s largest concrete gravity dam, has a maximum capacity of 432MW. Our largest wind farm, Turitea, which opened in the Tararua Ranges near Palmerston North in May, has a maximum output of 222MW. The country’s largest solar farm is just 2.1MW.

So we need roughly a Clyde Dam’s worth of new electricity generation built every year, or two of the country’s largest wind farms, or 230 of the country’s largest solar farms — every year, for 27 years.

Last year, modelling from the Electricity Authority (EA) found we might need even more — perhaps as much as 500MW of new generation and demand response (the ability to switch off some power consumption during peak times, such as to hot water cylinders) every year until 2050. “The projected pace of development is much faster than experienced in living memory,” the EA said. “As a comparison, net supply growth averaged around 60MW/year between 1990 and 2020.”

Clyde Dam hydro station. Photo: Jodie James

The challenge becomes greater when you consider that all of this new generation will come from intermittent renewable sources — mostly wind and solar. And it comes at a time when we’ve built very few new power stations, because demand for electricity has been flat for more than a decade due to increased energy efficiency and the scaling down of some industry. Our generation capacity has remained around 9500GW for the last 16 years.

But we’re beginning to get an idea of what meeting this immense challenge may look like. It’s not quite like anyone imagined.

A solar flare

It all seemed to happen at once. In March 2021, Transpower released its six-monthly report on the country’s progress to doubling power generation by 2050. It said there was an impressive 1247MW of new power projects being developed — almost entirely wind farms. Not a single solar project made the list. Within a year, that had transformed.

In June 2021, Todd Corporation’s Sunergise switched on the country’s largest grid-scale solar farm to date. It had a capacity of 2.1MW, boasting “enough renewable electricity to power over 520 New Zealand homes”.

The same month, then-prime minister Jacinda Ardern turned the first sod on what was to be the country’s new largest solar farm, a 16MW, 32,000-panel array on the Aupōuri Peninsula, built by a company called Far North Solar Farms.

The Climate Change Commission estimated there would be 950MW of solar farms by 2035… Now Transpower expects almost seven times that amount will be built in the next seven years based on the scale of projects announced in the last couple of years alone.

Then the pace of new developments skyrocketed. By May last year, Forsyth Barr reported there had been “a tectonic shift in view”. It found there were 8.75 terawatt hours (TWh) of solar projects being investigated, the equivalent of around 20 per cent of New Zealand’s electricity consumption. While solar had “long been spurned in favour of alternatives such as geothermal and wind”, it said there had been “a flurry of announcements of intentions to build grid-scale solar”.

It found less than a quarter of the projects were driven by existing power generation companies, with more than half of the projects coming from offshore investors, particularly from the UK and Australia.

One local company, Lodestone Energy, announced it had raised $300m to build five solar farms totalling 229MW. Its backers include Guy Haddleton, Rod Drury, Sam Morgan and Stephen Tindall. Another company, Helios Energy, raised $1.3 billion from investors including top Google executive Urs Hölzle, planning to build 1000MW of solar power projects.

Far North Solar also announced it had partnered with German investment firm Aquila Capital to build 1000MW of solar. UK company Harmony Energy announced plans for 500MW of solar farms, including a 147MW project near Te Aroha.

The goliath 400MW project near Taupō mentioned near the beginning of this story was granted a fast- tracked resource consent in November last year. It’s being developed by Nova Energy, which is also owned by the multi-billion-dollar Todd Corporation, which has had major interests in oil, gas and power generation for more than 50 years.

Within two years, there were more solar projects in the works than all of our existing hydro, geothermal, wind, coal and gas power stations combined.

In May this year, Forsyth Barr reported the pipeline of solar had grown to 15.9GW, with 1.9GW announced in April alone.

The rise of solar farms was largely unexpected. Transpower’s forecasts in 2020 predicted there wouldn’t be any solar farms here before 2030 and only one gigawatt of grid-scale solar by 2050. The Climate Change Commission estimated there would be 950MW of solar farms by 2035 if its recommendations were adopted. Now Transpower expects almost seven times that amount will be built in the next seven years based on the scale of projects announced in the last couple of years alone.

What’s going on?

Tectonic shift

Andrew Harvey-Green, who has been an energy analyst at Forsyth Barr for 15 years, says the solar boom has primarily been driven by economics. The cost of solar panels has fallen dramatically over the last decade — faster than many predicted — while power prices have increased in the last couple of years, primarily driven by gas shortages.

“Even in the late 2010s, solar was well out of the money in terms of new generation,” Harvey-Green says. “Wind and geothermal were much more attractive, but those costs kept on falling.”

The cost of solar is still generally higher than building a wind farm, he says, but solar farms can be built on a smaller scale and at a much faster rate, lowering the barrier to entry for new generation. With power demand set to climb rapidly, getting in early is also profitable.

“It takes two to three years to build a solar farm from an idea to completion. With wind it’s more like five to seven years. And New Zealand is trying to build new generation as quickly as possible and that’s why solar’s attractive, because it can get to market quicker.”

Part of the reason solar farms are quicker to build is that they are viewed as being easier to consent. While wind turbines tend to be built on hilltops and can be over 100 metres tall, solar farms tend to be built on flat land. The panels are only a couple of metres high, so can be hidden by planting trees. This can limit how many affected parties can have a say on a project. For example, the Naseby solar farm gained a non-notified consent as the effects were judged to be less than minor.

New Zealand has also been behind other countries in the uptake of solar, Harvey-Green says. Some of the companies building solar farms here have gained experience building large-scale projects overseas and are beginning to look further afield. New Zealand’s goal of being 100 per cent renewable by 2030 makes it look like a good investment. “A lot of larger offshore players were looking around and New Zealand probably stood out as one of the few countries that hasn’t developed a solar sector, so it’s seen as an opportunity.”

Brendan Winitana is chair of the Sustainable Energy Association of New Zealand (SEANZ), a group representing the renewable energy industry, with a membership now dominated by companies involved in solar power. He says solar farms require less due-diligence than wind projects. Building a wind farm sometimes requires two years of research into the vagaries of wind at a site before it is possible to secure finance, he says. Within that time, a solar farm can be consented and built.

But one of the most important factors, he says, has been the availability of finance. Globally, a lot of inventors have divested in fossil fuels and are moving funds towards renewable energy. That’s now flowing to New Zealand. “Nothing happens until you’ve got a funding line.”

Winitana says there has been pushback against solar in New Zealand in the past because of a belief the country isn’t sunny enough. But research from NIWA has found New Zealand is sunnier than many places where solar has been popular, such as France, Germany and the UK.

Still, Harvey-Green says only a fraction of what’s been proposed is likely to be built. He believes about 5 per cent of our power will come from solar farms by the end of the decade, a similar proportion to existing wind generation. Even once consented, many power projects won’t eventuate. One solar company in Hawke’s Bay has gone into liquidation, for example. One factor that could affect what goes ahead is the queue of 58 projects — three-quarters of them for solar farms — seeking connection to the grid. Some fear it could take years to clear.

Photo: George Driver

Solar’s shadow

While the solar boom may be good news for the country’s pursuit of decarbonisation, there are downsides. The footprint of a solar farm is much denser than the likes of a wind farm. While a 400MW wind farm may require about 100 wind turbines over 2000 hectares or so, a solar farm with the equivalent capacity will require covering about 60 hectares entirely in solar panels (based on SEANZ’s estimate of a solar farm requiring one hectare per 1.5MW).

Solar farms also generate less power per megawatt of capacity than wind, because the panels only generate at their peak around 20 per cent of the time. A wind farm on the other hand produces at peak around 35 to 40 per cent of the time. This means you need to install more generation to produce the equivalent amount of power. It’s the footprint that is drawing opposition. Some people are concerned about the loss of productive land, while others just don’t want to look at fields full of solar panels. In Helensville, north-west of Auckland, a group of residents have opposed a 53MW, 82,000 panel solar farm that would be about 500m from the outskirts of town. “We won’t be Helensville or Te Awaroa anymore if this goes ahead,” one resident told the NZ Herald, “we’ll be solar city.”

A number of residents have opposed a 160MW solar farm near Leeston, Canterbury, with concerns raised about loss of productive land. The application for a non-notified consent was declined in March after a commissioner said the application would need to be publicly notified due to the impact on productive land — the site is a dairy farm.

There has been similar public opposition to solar farms proposed in Greytown, the Waikato, Tekapo, Taupō and Rangiora.

Winitana says concerns about the impact of solar on views and productive land are overblown. Because solar panels only stand two or three metres off the ground and occupy flat sites, they can be largely hidden from view, he says. “Planning can ensure there’s no visual pollution from a solar farm if there’s vegetation coverage.”

Modern solar panels can also let light through so the land can still be farmed with sheep, he says.

Other practical issues arise, however. Solar power isn’t particularly suited to New Zealand’s electricity- demand profile. Our demand peaks on winter nights, a time when the generation from a solar farm is nil. When solar generates the most power — midday in summer — demand tends to be low.

Advocates say this can be addressed by hydro power stations generating less when solar power peaks, and more during peak-demand periods, though the ability to do this is currently limited.

Solar farm developers have also been matching developments to customers who need power the most at midday. For example, Genesis Energy is building a 52MW solar farm on the Canterbury Plains, to help power irrigation that peaks around midday in summer.

Longer-term, large batteries may provide a solution to ironing out the peaks and troughs of solar. Winitana says grid-scale batteries are already economical, though other experts say they remain too expensive to use at scale. Meridian Energy plans to build the country’s first large-scale grid battery later this year. It will be able to produce 100MW of peak power for two hours at a time, and will be linked to a 130MW solar farm near Marsden Point, in Northland

University of Otago senior research fellow Jen Purdie, whose work focuses on “the nexus of climate and energy”, says solar and wind complement each other in our energy mix. “Solar tends to generate more when there is less wind, at midday, and wind generates more in the early evening and morning.”

They also use different types of land — flat terrain versus hills — spreading the footprint of new renewable generation. This is important, because powering our future is likely to require a lot of land.

The renewable footprint

When Ralph Sims looks out the window of his Palmerston North home, he can see the country’s newest wind farm, Turitea, being built. To him, the gleaming white turbines on the Tararua Range are a thing of beauty.

Sims, an emeritus professor of sustainable energy and climate mitigation at Massey University, has been a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. He says while it is technically possible for the country to double its power generation capacity, because the wind and solar resources are there, the challenge is where they can be sited at the scale required. Most people aren’t as fond of looking at turbines out their window.

“Everybody wants electricity, but nobody wants power stations,” Sims says. “That’s the conundrum we’ve got.”

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests we might need tens of thousands of hectares of renewable power generation by 2050, based on the scale of some recent solar and wind projects. Although determining how much land is “impacted” by this amount of generation is somewhat subjective.

Some environmental groups have called for more regulation on how and where we grow our electricity network. On the other hand, those wanting to build new renewable generation are calling for existing restrictions to be relaxed to ensure new plants are built at the pace required.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests we might need tens of thousands of hectares of renewable power generation by 2050, based on the scale of some recent solar and wind projects.

The government seems more persuaded by the latter argument. In April, it released proposed changes to make it easier to consent renewable electricity by ensuring the national benefits of new generation are taken into consideration through the consent process.

Environment minister David Parker told RNZ that the country was going to have to accept there would be more wind farms and other renewable generation projects in their backyards. “There are some detractions from visual amenity that we’re going to have to put up with as a country if we’re going to get the renewable generation that we need.”

The National Party has also proposed changes to make consenting faster. This includes requiring resource consent decisions to be made within a year and for consents to last for 35 years.

An MBIE consultation document on the government’s proposals said: “Our current resource management settings don’t allow us to build the renewable electricity infrastructure at the rate needed.”

The changes include “enabling renewable electricity generation activities in areas with significant environment values… when their benefits outweigh residual remaining adverse effects”.

This has Environment Defence Society (EDS) chief executive Gary Taylor concerned. Taylor has been fighting against the negative environmental impacts of power generation projects for about 50 years. He was involved in an EDS court case to halt the Clyde Dam in the 1970s.

He says the country seems to be slipping back into the “Think Big” era, by weakening environmental protections to enable industrial-scale projects. “It’s a one track mind — rip, shit or bust. There’s nothing nuanced or sophisticated about the thinking,” Taylor says of the proposed RMA changes. “That discussion document is frankly a disgrace.”

He says, in his experience, when decision- makers have been allowed to balance national benefits against environmental costs, “every time the environment loses”. While Taylor believes the country needs to rapidly scale up renewable generation to decarbonise, he says this needs to be done in a way that protects areas of high natural values. This could be achieved by investigating what kind of generation would best meet our needs with the lowest footprint, rather than leaving it to the market. The government could then designate zones for where generation could be built with the least impact.

“The answer isn’t just to fast-track and crack through and remove the barriers,” he says. “It’s actually to do some strategic thinking about what can go where. Is there enough lower value land to accommodate all of this stuff? And if there is, let’s develop a permissive regime for that and protect the best bits. That will provide not only a good environmental outcome, it will provide a good climate outcome and it’ll give the sector a bit more certainty about where they can go.

“We can’t lose our heads in the rush to renewables. We’ve got to be working towards good environmental and climate change outcomes, and not sacrifice one on the pillar of the other.”

Taylor is also sceptical that current regulations are a barrier to building enough renewable generation. MBIE estimates 1447MW of wind farms and 1010MW of solar farms have already been consented, which would expand our generation capacity by about 25 per cent. In March, Transpower reported there were 30GW of new renewable generation “in the pipeline” — about half of which were solar farms. While most of the projects were in an early stage, the state-owned enterprise believed the country was already on track to more than double our generation. “Overall, this signals strong and growing interest in renewables, large enough to meet the Accelerated Electrification demand forecast of 22GW and 70TWh by 2050.”

The electricity industry disagrees. The Electricity Sector Environment Group representing the major gentailers says in its submission on the government’s proposal that unless changes are made New Zealand won’t meet its electrification and decarbonisation targets or its climate-change mitigation commitments. It wants the consenting regime even more permissive than what’s proposed.

A rooftop solution?

When Sir Grahame Sydney looks out the front window of his studio near St Bathans, he can see the snow-flecked face of the Hawkdun Range — the mountains which have served as the backdrop to some of his most renowned landscape paintings. When he looks out the back window of his studio, however, he sees solar panels. Ironically, it was his efforts to stop large generation projects that ultimately led him to generate his own electricity from an 18-panel solar array in his backyard. “I think it’s a necessary gesture towards sustainability,” he says. “You can’t be a critic of the system without putting your money where your mouth is.”

Sydney says he took an interest in power generation while living on Mt Pisa Station near Cromwell in the 1970s. The Muldoon government was investigating building a series of hydro dams — or one monster dam — on the Clutha River. Concerned about the landscape that would be flooded and lost, and at what he describes as a shaky rationale for the scheme, he joined efforts to stop the dam.

While those efforts ultimately failed, in 2006 he joined the fight to stop a wind farm, dubbed Project Hayes. This would have seen the largest wind farm in the Southern Hemisphere (a mammoth 630MW, with 176 turbines) built atop Central Otago’s Lammermoor Range, which is classified as an outstanding natural landscape of national significance. “I was horrified by the thought of what it would mean, visually, so I started learning about it.”

Meridian Energy gained consent for the project in 2007, but the company abandoned it in 2012 following court appeals from environmental groups and individuals, including Sydney.

A decade on, he’s concerned about what more the country might lose as the renewable energy gold rush begins. He says our landscape attracts millions of people from around the world.

“We have to make sure that we recognise the value of our natural environment in its most pristine state possible, because that’s what people want to see and enjoy and be amongst,” he says. “And all of these power schemes we’re talking about, to me, are detrimental to that landscape’s appeal.”

Home-scale solar projects could help prevent thousands of hectares from being covered with solar farms or wind turbines, Sydney says. This would also make people aware of where their power comes from, and hopefully spur them to conserve it.

Greenpeace is also advocating for household solar projects to be given priority over large scale commercial projects. “Just because energy production is renewable, it’s not necessarily sustainable,” Greenpeace lead climate campaigner Christine Rose says. “The adverse environmental and social impacts of the centralised ‘Think Big’ generation model can be addressed by rooftop solar and battery storage.”

Sir Graham Sydney has his own solar panels, but worries big wind and solar farms will ruin the landscapes. Photo: George Driver

New Zealand has a relatively small amount of rooftop solar. By the end of last year, only 2.3 per cent of households had solar panels, totalling 193MW. But this is growing fast, with 48MW of residential solar installed last year and it’s been growing at an average rate of 40 per cent. When including commercial and industrial solar connections, the total capacity of distributed solar (small-scale and not connected to the national grid) rises to 259MW.

By contrast, in Australia almost a third of households have rooftop solar, generating 9 per cent of the country’s electricity.

In 2019, a Transpower report found that if 58 per cent of households and 25 per cent of businesses in New Zealand had rooftop solar it could provide more than half of the power generation required. If 69 per cent of households and 40 per cent of businesses install solar, it found it would generate two-thirds of our current power consumption.

Those building solar farms, however, say building at scale is faster, cheaper and more efficient than a network of home-scale generation projects.

In 2020, the government committed $28 million for “renewable energy technology, such as solar panels and batteries, on public and Māori housing”. This fund was increased by $30 million in this year’s budget.

Energy Minister Megan Woods says there is “scope for far wider roll-out of solar,” but has made no commitment to any expansion of funding. “The question is working out what role government needs to play in this, given the short payback rates on solar now,” she says.

Out to sea

There are alternatives. As of March, Transpower has received “around 4-5GW” of interest for offshore wind farms. A partnership between Spanish company BlueFloat Energy and New Plymouth-based energy company Elemental Group is planning to build about half of that. It has announced plans for a 900MW farm off the south coast of Taranaki and another 1GW wind farm off the coast of Port Waikato.

The consortium’s partnerships director Justine Gilliland says offshore wind farms are built 22km out to sea and are almost invisible from land, appearing as dots on the horizon. They can also use much larger turbines than on land — around 15MW, rather than around 4MW. The wind at sea is also stronger and more consistent, meaning offshore wind farms generate power around 60 per cent of the time, compared with around 35 per cent on land.

The downside of offshore wind farms is they are expensive, producing power at about twice the cost of onshore wind. They also take a long time to consent and build — Bluefloat’s projects are expected to take almost a decade before they will generate their first electrons.

There aren’t even rules yet for who can build an offshore wind farm, where, and under what conditions. The government is drawing up a “regulatory framework” to be in place by next year.

And while New Zealand has a lot of coastline, there aren’t many sites that have the relatively shallow seas required for fixed turbines, with the best sites near Taranaki. Bluefloat’s Waikato project could include floating turbines, which are more expensive and relatively new technology.

However, Gilliland says it’s unlikely we’ll be able to build 4-500MW of new generation each year if we are solely reliant on onshore sources, and unlikely to be willing to accommodate that much. “The amount of land occupied to generate that kind of scale of onshore wind and solar is probably going to reach a point where we would need to start asking questions about ‘is that really what we want to be using our land for?’”

Ralph Sims says in future, small-scale nuclear power may prove more economic, and may be more palatable to the public if mass scale wind and solar farms are the alternative. “The technology is evolving and we can’t totally discount that option I think.” Tidal generation may also be developed in future.

Sims says while the landscape will change with the challenge ahead, so might our attitudes. “People don’t like change, but you won’t find many people in Palmerston North now who object to the wind farms in the Tararuas, which are very visible from here. We’ve even named our Manawatū rugby team the Turbos. It’s a fear of the unknown mostly, I think.”

On the other hand, while he’s got solar panels on his roof, he’d rather not have a solar farm going in next door. “It’s a personal view, but I’ve seen many solar farms in the UK and the States over the last 10 or 20 years, and they’re pretty ugly things as you drive past, I reckon. Whereas I quite like the look of wind turbines. But it’s a very personal view and you’re going to get some people who object to one system purely on their aesthetics.”

In Clyde, the lake created by the dam flooded a valley of fruit trees above a rugged gorge. That gorge is something I’ve never experienced. Now tourists come from around the country to bike alongside Lake Dunstan on a new cycle trail.

When I get home to Clyde from Naseby, the Clutha River is beginning to swell again as dark sets in. There hasn’t been a ray of sunshine in nearly a week. At night, the spillways roar again.

George Driver is North & South’s Southern correspondent, a role made possible by NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the August 2023 issue of North & South.