A burning question

New Zealand could one day be burning hundreds of thousands of tonnes of rubbish each year to generate electricity. Advocates say it’s an environmentally friendly alternative to landfill, others say it will pollute the air, endanger people’s health and encourage more waste. Who is right?

By George Driver

It looks like a scene from a Fonterra ad. Fields of green pasture stretching along fertile plains, from the snow-capped St Marys Range in the distance to the Pacific Ocean 4km behind me. The Waitaki River weaves towards the sea in the middle ground, unseen. Nearby, a milk plant, run by Fonterra’s Chinese-owned competitor, Oceania Dairy, chuffs out steam. The air’s permeated by the sour tang of silage. The only sound is the white noise of traffic from State Highway One a few hundred metres away, and the hum of tractors distributing winter feed.

In a grass swale on the roadside, I can see a McDonald’s drink cup, a wrapper from a Calippo ice cream, and a crushed Lift+ energy-drink can. It’s the kind of rubbish that litters rural roadsides around the country. Ideally, if it’s not thrown out a car window, this rubbish is buried in a landfill, recycled in a New Zealand facility or baled up and shipped off to a third-world country. But a more novel solution is being proposed.

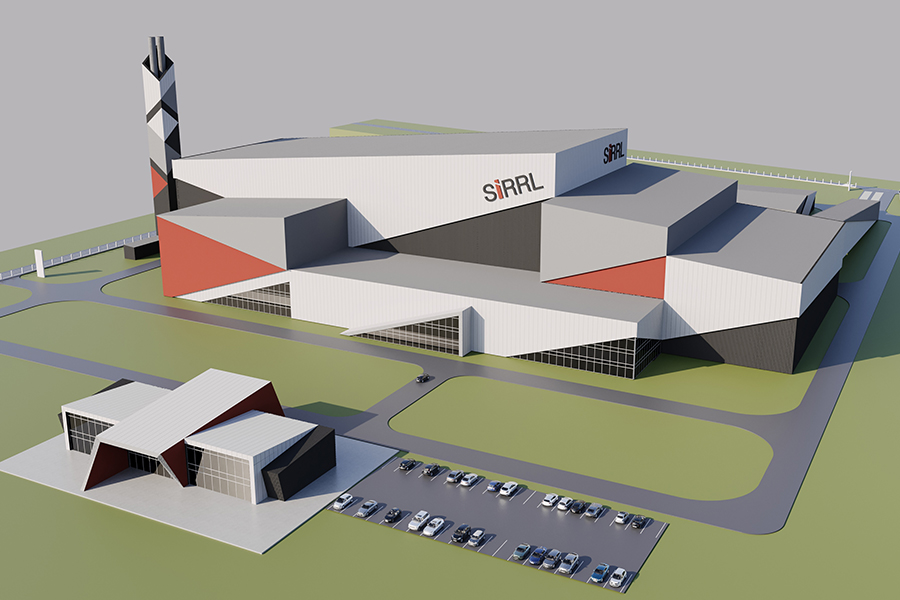

In the field before me, near the small township of Glenavy, about 25km north of Oamaru, a company called South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) has lodged a resource consent to build an incinerator that could burn about a fifth of the South Island’s rubbish — 365,000 tonnes a year — and use the heat to generate enough electricity to power 30,000 households.

Around the world, hundreds of these waste-to-energy plants have been built, and in some European countries they’ve helped all but eliminate landfill. But nothing like this has been built in New Zealand before.

Now, around the country, at least four waste-to-energy plants are being investigated in small rural communities. If built, they could potentially burn the bulk of the rubbish from the country’s main centres.

The plant proposed near Glenavy has been almost a decade in development, and is something of a test case in a debate that will have national implications. SIRRL says burning the rubbish in a state-of-the-art plant and generating power avoids the stench, leachates and methane emissions involved in landfill. But those opposing it say the smoke from the incinerator could pose a serious health risk for the people of Glenavy, and will drive up greenhouse emissions and lock us into a wasteful future.

It all started on the West Coast.

The proposed site of an incinerator near Glenavy, about 25km north of Oamaru.

The Wild West

Ashburton farmer Paul Taylor was backpacking through Europe a couple decades ago when he discovered that much of the continent’s rubbish wasn’t buried in the ground and left to rot, but burned to create power. In a phone interview with North & South, accompanied by a representative from a public relations company, he reveals it was an experience that would later change his life. “I thought at the time, ‘that’s a great idea’,” Taylor says. “Why aren’t we doing that in New Zealand, rather than burying rubbish in the ground?’’

Taylor has spent the last eight years trying to do just that in a number of small South island towns. Company records show efforts began in May 2015, when a business called N2ENZ limited (later renamed Renew Energy) was registered by a man called Gerard Gallagher, who was then sole director, sole shareholder and CEO. Taylor became a shareholder later that year, along with Timaru businessman Murray Cleverley. Taylor is now a director and the company’s largest shareholder (more on the other two later).

Ashburton farmer Paul Taylor is a director of Renew Energy and South Island Resource Recovery Limited.

Taylor says the company began with a “small investment group” who were invited by Buller mayor Garry Howard to investigate building a waste-to-energy plant in Westport.

The town was going through a rough patch. About 150 jobs had been axed at Stockton coal mine and the local Holcim cement plant had earlier announced it was closing, impacting another 100 jobs. Someone had the idea of building a waste-to-energy plant in the old Holcim site to help revive the local economy.

Initially the project progressed rapidly. The mayor invited economic development minister Steven Joyce to visit, and he met with a French waste multinational, Veolia, that had built plants overseas. Joyce recommended Renew Energy apply for a grant for a feasibility study from the Ministry for the Environment’s (MFE) Waste Minimisation Fund.

When the application came through a few months later, MFE was less enamoured. An expert panel said the proposal was “highly unlikely to be economically viable”. Waste-to-energy plants tended to require an enormous volume of rubbish to be viable and were typically built near big cities, it said, not in an isolated town with a population of about 4000 people.

Taylor explains that Buller was attractive because coal wagons travelling from the West Coast to the East Coast were returning empty, and the wagons could be filled with rubbish for the return trip.

There were other incentives. In 2016, Buller council business development facilitator John Hill said a waste-to-energy plant was being investigated in Buller because “it would be easier to obtain resource consents” for a plant there. “Two advantages of Buller,” he told the Westport News, “we’ve burned coal for years, we have consents in place already at Holcim for burning coal, and secondly we’re not Nimby people — we tend not to object to activities.”

Later that year, a report on economic development opportunities on the Coast revealed Renew Energy was proposing an enormous facility that would rely on burning coal. It said it would “initially use 300,000 tonnes of waste annually to generate 60MW of power” and potentially double in scale after a few years. To put that into perspective, the entire West Coast sends about 11,000 tonnes of rubbish to landfill each year. The report said the plant would rely on burning municipal waste, waste coal and tyres imported from around the South Island.

Taylor says the company never looked at burning coal in their plants. “It’s not something we were looking at,” he says. “We were looking purely at residual waste streams. It [coal] was never really on the agenda.” However, the MPI report said burning coal was one of the only things that made the project’s location make sense. “The rationale for establishing the facility in Buller is to have ready access to the waste coal which will help to ensure minimum energy levels are generated,” the report said. “If the facility only made a limited use of local feedstock, we would question the rationale for establishing it on the West Coast rather than being closer to the major sources of waste. However, the use of waste coal means the location makes more sense.”

Government money flowed into the project regardless. In 2016, government agency New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (NZTE) contributed $50,000 towards a feasibility study for the plant — it was never published due to commercial confidentiality. Then in February 2018, regional economic development minister Shane Jones announced $350,000 of funding for another feasibility study as the government launched its $3 billion Provincial Growth Fund.

Here things began to unravel. Five days after the funding was announced it was revealed that Renew Energy’s founder, Gerard Gallagher, was being investigated by the Serious Fraud Office. In 2017 the State Services Commission (SSC) looked into reports that Gallagher and a colleague had used inside knowledge from their work for the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) to profit from property deals. The commission found their actions amounted to unacceptable and serious misconduct. Murray Cleverley was also involved with both CERA and the property business under investigation, but he was found to be unaware of the business’s dealings. The commission said he made a “significant error of judgement” in not disclosing his connection to the business. The case was referred to the Serious Fraud Office; Gallagher was convicted of fraud for the corrupt use of official information this year and is serving a sentence of home detention.

Mayor Howard seemed unfazed at the time. He told RNZ he had no concerns about Gallagher. “History is history, we’re talking about Renew Energy and a totally different scenario.”

The government was more concerned, however, and funding for the project was put on hold and later abandoned due to the controversy. A subsequent MBIE investigation found it did not undertake sufficient due diligence and revealed that MFE thought it was a bad candidate for funding in any case.

MFE advice said waste-to-energy plants generally reduced recycling rates and threatened new investment in waste-reduction infrastructure and products because burning waste would become an easy alternative. “Although waste-to-energy (incineration) is used in other parts of the world to generate electricity, it is a technology that comes with a range of negative environmental impacts, human health concerns, and high financial costs… even the latest technologies still emit large quantities of greenhouse gases and release a range of harmful pollutants, such as toxic metals and dioxins, that can contaminate our land and water.”

Gallagher resigned as CEO of Renew Energy in 2017 and sold his shares, but was still paid by the company as an independent contractor until late 2022. Cleverley had sold his shares in Renew Energy in 2017.

Work on the waste-to-energy plant ploughed on regardless. In May 2018, it was announced Renew Energy had partnered with Chinese waste company, China Tianying Inc (CNTY), to build the plant.

Government sources claim CNTY is partly owned by the Chinese government. When I ask Taylor about what the links to the Chinese government are, he says he doesn’t know. “They’re a large public company, so I’m not sure whether they’re linked.” He then asks his PR spokesperson to respond. She says most large Chinese companies are partly owned by the Chinese government. “In this case, when due diligence was done there wasn’t anything in CNTY’s background that SIRRL believed to be problematic, but the reality is that Chinese companies are structured in a different way. Like I say, I’m not a Chinese expert, but you’d have to ask a Chinese expert about what the relationships are there, because also you’ve got other disclosures, etcetera.”

Anyway, Renew Energy later paid for Garry Howard to travel to China to visit a plant near Shanghai. The company’s directors, including Gallagher, had also earlier accompanied Howard on a trip to England to visit waste-to-energy plants there, at ratepayers expense.

Then things got worse for the project. In 2019, Stuff obtained emails which showed Howard had signed an agreement with CNTY “in secret without approval of his council” while in China. The agreement said “the council would supply water, build a road to the plant, own the land and lease it back to the company” and would supply a landfill for toxic ash from the plant. None of these details were considered by the full council, Stuff reported. Taylor denies there was an agreement.

Other emails showed that Renew Energy’s directors had urged Howard to keep information from the public. Howard had also lobbied the government to support the project “despite having no formal mandate from the council or public to support the proposal”.

The emails also showed Gallagher had asked council to legally threaten a journalist writing about the proposed plant, to get them “sorted out once and for all”.

There were also perceived conflicts of interest. One of the company’s directors, Kevin Stratful, was the economic manager for the West Coast regional council and a consultant for Development West Coast. It was revealed he had promoted the waste-to-energy plant via his work emails.

Stratful had also advised the council on how to avoid official information requests. He denied there was a conflict of interest and later resigned from his council roles.

Then Reefton became involved. In January 2019, Renew Energy lodged a resource consent to store 132,000 tonnes of baled rubbish near the town. There was strong public opposition to the idea. A meeting opposing the plan attracted 250 people, about a quarter of Reefton’s population.

Residents were concerned they’d be left with a mountain of rubbish if the plant went bust. The town’s business group went as far as employing a queen’s counsel to oppose the plan. The protests worked and the consent application was soon withdrawn.

Later events suggest their fears might have been justified. Baled waste was stored in and around Christchurch without resource consent for a number of years before the company contracted to store it, ERP Group, went into voluntary liquidation in 2021, leaving thousands of bales of rubbish that had to be sent to landfill at considerable cost.

Paul Taylor says ERP Group had taken on the risk of the project and “it certainly had nothing to do with” SIRRL — the company proposing the Glenavy plant, which is 40 per cent owned by Renew Energy. However, documents show Renew Energy applied for the resource consent to store the waste near Christchurch. Environment Court documents state that Renew Energy was the owner of the baled waste, while ERP Group held the resource consent for the transfer station there.

The project in Westport couldn’t survive the mounting controversies. Taylor says it was killed off by “politics”. Howard faced a vote of no confidence in 2019 which was supported by all but one councillor; he didn’t contest the mayoralty in 2020. Renew Energy then abandoned its plans for Westport. At the time the company’s CEO said it was because “it did not have the support of the residents”.

Renew Energy soon popped up again in Hokitika. The mayors of Grey and Westland districts both announced they were keen to host the plant, eyeing jobs and investment. The company began looking at building a plant in Hokitika in mid 2019 but again faced strong public opposition and the proposal faded from view.

Then it resurfaced again.

Why Waimate?

In September 2021, a press release was sent out to media. South Island Resource Recovery Limited (SIRRL) was spruiking plans for a $350 million waste-to-energy plant near Waimate, a district with 7815 people, 6km off State Highway One, between Oamaru and Timaru.

SIRRL said the plant, dubbed Project Kea, “will safely convert 350,000 tonnes of waste, that would otherwise be dumped into South Island landfills annually, into renewable electricity”. It came with an apparent endorsement from Waimate mayor, Craig Rowley, who called it “an exciting proposal which could create many benefits for the district,” including jobs and economic growth.

Many were confused why a company would want to truck rubbish from around the South Island to burn it in an enormous incinerator in the small South Canterbury town. Local artist Robert Ireland went along to a public meeting hosted by SIRRL to understand why and what impact burning all of that rubbish might be, but left with more questions.

Waimate mayor Craig Rowley called it “an exciting proposal which could create many benefits for the district,” including jobs and economic growth.

“They were just salesmen, they didn’t really have the answers,” he says.

Ireland did some digging and discovered Renew Energy’s past projects on the West Coast. “They were making out that they were bringing this to Waimate because the location is perfect, but then I found out we were at least the third in line.”

SIRRL has been eager to distance itself from the plants proposed on the West Coast, emphasising the project isn’t being driven by Renew Energy, but a new international joint-venture. Taylor has said it is now “a much more robust company” and has conceded mistakes were made on the West Coast.

However, the project consists of the same basic partners. Renew Energy is a 40 per cent shareholder of SIRRL, while CNTY owns 41 per cent of the company, and a Belgian-based CNTY subsidiary, Europe ZhongYing, owns 19 per cent.

Many of the people are also the same. Gallagher worked as a contractor for SIRRL until late 2022, and Kevin Stratfula and Paul Taylor (who has been a director of Renew Energy since 2016) are directors of the company.

Robert Ireland helped found an opposition group, Why Waste Waimate. A central suspicion is that Waimate has been chosen because it’s a small rural council and the company will face less opposition. “Why are these guys targeting small towns and not areas like Christchurch where there’s a large waste source and the infrastructure to support it?” Ireland asks.

Taylor says the company decided to relocate to the east coast after realising it made sense to be closer to the main sources of waste. He says the company looked for a site between Christchurch, Dunedin and Central Otago. Last year, it announced it had purchased a block of farmland about 2km north of Glenavy, a place that’s little more than a dairy, a petrol station, a school and a campground near the banks of the Waitaki River. Taylor says the location was perfect — close to State Highway One, beside the main railway and near the Oceania Dairy factory, which might be able to use the heat from the plant.

Left: An artist’s impression of the proposed waste-to-energy plant in Waimate District. Below: The award-winning Amager Bakke waste-to-energy plant and sports park (including a ski slope) in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Photo: Shutterstock

But Ireland questions how it will be able to get enough waste, especially when the country is trying to increase recycling rates and reduce rubbish. “A smaller plant near a large population base, maybe, but it’s still not addressing waste at the source and a lot of what these guys are planning to burn could be used in future recycling initiatives.”

The proposed plant could process about 1000 tonnes of rubbish a day. A BERL report said Renew Energy’s West Coast plant required a minimum of 250,000 tonnes a year to break even, which is more than the 217,503 tonnes of municipal waste from Christchurch City. And it will need that volume of waste every year for the next 20 to 30 years.

Taylor says it won’t burn any recyclable rubbish and there’s more than enough waste to supply it. “In the South Island, we’ve identified in the order of 1.8 million tonnes of materials that could be processed through the plant, so we require less than 20 per cent of what is currently being produced.

“We expect that the percentage of residual waste as a portion of the total volume of waste will reduce over time, but the total volume of waste will probably stay relatively constant because of population growth.”

The government, meanwhile, has a target of reducing the amount of waste per person by 30 per cent by 2030. Reports by MFE and Berl have also highlighted that while the waste may exist, it is usually tied up in long-term council contracts. They say it’s unlikely councils and waste-management companies will send their rubbish to an incinerator when many have invested tens of millions of dollars building new landfills, which generate revenue.

Taylor claims it has “understandings and agreements in place” with waste management companies that amount to a “significant chunk” of the 365,000 tonnes required, because their facility will be cheaper and reduce greenhouse emissions. “The councils in a lot of places don’t actually own the waste,” Taylor explains. Instead, the company has agreements with waste contractors “such as Waste Management, Envirowaste and Ecowaste” that collect waste on behalf of councils.

“It would be unwise for us to go and contract a lot more at this point — because there’s considerable interest from a number of the larger waste-collection companies — but for commercial reasons we can’t really talk about it.”

The country’s largest waste-management companies and a number of South Island councils say they won’t send waste to the incinerator. Waste Management is the largest waste contractor in the country. Its managing director, Evan Maehl, says it has contracts for about a third of the South Island’s waste and has no agreement or understanding with SIRRL and would not supply waste to the plant. He says the company doesn’t decide where municipal waste goes as this is determined by district councils.

Until September last year, Waste Management was owned by Chinese company, Beijing Capital Group, which operates large waste-to-energy plants in China. Maehl says the company investigated building these plants in New Zealand and found it was uneconomic. He says plants are only viable overseas with government subsidies.

“I don’t want to state the obvious,” he says, “but you’ve got the largest waste company in New Zealand, that used to be owned by a Chinese company that operated 10 of these facilities in China, so why aren’t we doing it?”

The country’s second largest wastemanagement company, Enviro NZ (formerly EnviroWaste) says it has no agreement or understanding with any proposed waste-to-energy incinerator. The company has waste and recycling collection contracts with councils including Dunedin, Central Otago, Timaru, Mackenzie, Waimate and West Coast. “Each council decides where the general waste we collect on their behalf is disposed of,” a spokesperson said.

Representatives from councils in Central Otago, Queenstown, Dunedin and Christchurch also said they had no agreements to supply waste to the SIRRL incinerator and all had agreements and significant investments in existing landfills.

Some suspect that the plant will need to import waste from overseas to ensure it has enough fuel to generate power. This already occurs in some Scandinavian countries, which import waste from around Europe to supply dozens of incinerators.

Taylor, however, is adamant SIRRL won’t import waste. “We would never embark on a plant if we thought that we were likely to have to import waste.” But, in 2018, when Stuff asked why the company was proposing a plant in Westport, Renew Energy’s then-chief executive David McGregor said: “One of the reasons for Westport was because of the port facilities. We can bring material from the [Pacific] Islands and Australia.”

Smoke and mirrors

In the gravel roads near the site of the proposed incinerator, a number of families are left wondering what the plant might mean for their lifestyle, livelihoods and health. Sharemilkers Hannah and Allon Wood have three children at the local school in Glenavy. They say they will probably move if the plant is built. “We’ve been here 12 years,” Allon says. “We like to call this place home, but if this goes through I don’t think we can be proud to say that with that on the back door.”

“It’s just not worth the risk,” Hannah says. “We hope we don’t have to leave this place, but you don’t want your kids growing up with these unknowns.” Their children bike to school and they are worried about the 68 trucks that would come down the small rural roads each day. They are also concerned about the potential health risks from emissions from the plant.

Glenavy School has 126 pupils about 2.5km downwind of the incinerator. Board chair Adam Rivett says SIRRL made the school aware it would be able to apply for new community grants, but the school isn’t interested. It doesn’t support the project, he says.

“We’re trying to educate our kids about the right thing to do with our rubbish and we’re not sure the best option is to burn it,” Rivett says. “We’d like to think we could get to the stage of not creating the waste in the first place.”

The school is also concerned about potential health risks. “There is risk in everything,” Rivett says. “One side says there’s no risk and the other side says there’s lots of risk and we’re sort of in the middle. But we’re not sure we want our children to face health risks in order to give everyone else in the South Island the convenience of burning their rubbish.”

Others are concerned, too. Down the road, on State Highway One, a sign written in big red capital letters reads: “Owners of incinerator get big fat profits, people of Glenavy and Morven get cancer”. During a protest against the plant in Waimate in March, more than 100 people stomped down the main street chanting, “No, no, no you can’t, we don’t want your poison plant”.

“We’re not sure we want our children to face health risks in order to give everyone else in the South Island the convenience of burning their rubbish.”

Waste stats

New Zealand generates about 17.5 million tonnes of waste a year, about 12.5 million tonnes of which goes to landfill. About 3.38 million tonnes ends up in “class one” landfills which cater for municipal waste.

The amount of municipal waste going to landfill increased by 48 per cent between 2009 and 2019.

On average, the country produces about 740kg of municipal waste per person each year, which is more than just about any country in the OECD.

About 28 per cent of our waste is recycled and the rest is sent to landfill. In Europe, 48 per cent of municipal waste is recycled, 23 per cent is sent to landfill and the rest is incinerated.

Photo: Shutterstock

Exactly what the health risks might be is difficult to determine. Many reliable sources say if modern technology is used and well maintained, the risk is low. An artificial ski slope has even been built on the roof of a waste-to-energy incinerator in Copenhagen, just below the plant’s smoke stacks, and many plants in Europe are in urban areas. But if things go wrong, there can be issues.

A central concern is dioxins, which are highly toxic pollutants, sometimes called a “forever chemical” because they take a very long time to break down and can accumulate in the food chain and the body. They have been linked to a number of health issues, including cancer and birth defects.

Dioxins are typically a by-product of combustion and are also produced by some chemical plants. A UN report on waste-to-energy states, “globally, waste incinerators are one of the leading sources of dioxins and furans [another long-lived pollutant]”. However, while incinerators built between the 1970s and 1990s have caused “a large amount of air pollution”, the report says “plants with advanced emission-control technologies that are well maintained have minimum public health impacts”.

Sometimes things go wrong, however. The report notes that “mismanaged thermal [waste-to-energy] plants have been shown to produce unsafe emissions, despite advanced emission control technologies”. It gives an example of high levels of dioxins being found in the eggs laid by chickens near a plant in the Netherlands, “despite the plant being equipped with advanced emissions control technologies and stringent emissions limits”. However, the Dutch study was conducted by an environmental group opposed to waste-to-energy plants.

Public Health England has stated that modern, well run and regulated municipal waste incinerators are “not a significant risk” to public health. “While it is not possible to rule out adverse health effects from these incinerators completely, any potential effect for people living close by is likely to be very small.”

Dr Peter Tait, an honorary senior lecturer at the Australian National University medical school, published a paper in 2019 reviewing studies into the health impacts of waste incineration plants. It found “older incinerator technology and infrequent maintenance schedules have been strongly linked with adverse health effects”. While more recent incinerators have fewer reported ill effects, it said this may be because of inadequate time for these to emerge, so “a precautionary approach is required.”

In an interview with North & South, Tait said the evidence “isn’t amazingly robust” due to limitations in the studies. It was difficult to prove to what extent the health effects were linked to pollution from incinerators, or other sources. But he says the plants are still capable of producing dangerous pollution and regulations need to ensure they are rigorously monitored and maintained and built in areas with few people downwind. “Because of the potential risk, we need to be more careful.”

Tait says monitoring also needs to ensure that dioxins and other chemicals aren’t getting into the food chain via nearby dairy farms. “That’s an important consideration.” Those building the plants should also be required to pay for independent long-term monitoring of the health of nearby residents, he says.

Tait says New Zealand should have a parliamentary inquiry to see whether further regulations are needed.

It’s important to note that landfills are the largest source of dioxins in New Zealand. An MFE report shows they were responsible for more than half of dioxin emissions in the country and were overwhelmingly the greatest source of dioxins.

Masterton waste and recycling centre.

Landfill fires were also the most significant source of past dioxin emissions to air. The number of landfill fires has declined markedly, but 81 were recorded in 2020. In November 2020, pregnant women and breastfeeding babies were advised to evacuate Glen Afton and Pukemiro, west of Huntly, after a private landfill caught fire and burned for months.

Paul Taylor says SIRRLwill use the best technology to treat emissions from the plant and the release of dioxins and other harmful chemicals will be well below permitted levels. Its resource consent application says any health risks are “negligible”.

Dr Crispin Langstone was one of a group of Waimate doctors who raised concerns in an open letter that pollution from the plant could pose a health risk. After doing further research and talking with SIRRL, he says he believes dangerous emissions can be effectively controlled using modern treatments. But he still believes there are unacceptable risks if anything goes wrong.

“If it’s running perfectly with no faults, then there is probably a bigger health risk from the trucks bringing the rubbish in than from the plant itself,” he says. “But what happens when it doesn’t work well? What happens in a disaster, like a fire or a major failure of a filtering system, or a slow leak. SIRRL says it won’t happen, but to me, you can never say that. Then you ask, do we need it? And I would argue that we do not.”

Langstone says he has little trust in SIRRL to manage the plant. “SIRRL have proven themselves to be unreliable in their openness and honesty.”

The ability of Environment Canterbury Regional Council (ECan) to enforce regulations. Allon says when the Oceania Dairy factory was proposed in 2009, residents were told there would be no odour from the plant, but he says just about every week there is a foul smell like rotten eggs when wastewater is discharged onto nearby paddocks.

“You ring ECan and nothing ever gets done,” he says. “They come maybe a week later when the smell has gone. I don’t have faith in ECan to police it properly.”

Coming to a town near you

The waste-to-energy plant proposed near Waimate is one of a number being investigated around the country. Last year, a Hamilton-based metal-recycling business called Global Contracting Solutions announced plans for a waste-to-energy plant in Te Awamutu.

The plant will burn up to 150,000 tonnes of rubbish a year, producing 15MW of power. About half of the rubbish would be municipal waste, while 10 per cent would be unrecyclable material from its car scrapping business, 20 per cent would be old tyres, and 20 per cent would be “plastic”.

The proposed site is in Te Awamutu’s industrial zone, beside a residential area and about 300 metres from a wānanga and a school.

The resource consent was publicly notified last year, but was on hold for many months after the council requested more information.

Another plant was proposed on councilowned land in Fielding by Australian company, Bio Plant. It would process about 40 tonnes of municipal waste and plastic each day. Rather than burning the waste, the plant would use a process called pyrolysis, which involves heating up waste without oxygen to produce heat to generate electricity, and diesel and charcoal which can be used as fuel.

Bio Plant withdrew its resource consent application in June after an expert report found there was insufficient information and “fundamental errors” in modelling supplied by the company. Council planners later recommended it be declined.

At the time, Bio Plant said it intended to re-apply for consent. The company did not respond to emails requesting an interview. Its website states it is also investigating plants in Gisborne and Hokitika.

Kaipara District Council recently voted to investigate building a waste-to-energy plant in the region, which could cater for Auckland and Northland’s rubbish. In the 1990s, Kaipara mayor Craig Jepson was a spokesperson for a proposed waste-toenergy plant that would burn up to a million tonnes of rubbish a year in an old coal-fired power station near Hampton Downs. The plan was abandoned in 2000 after long delays in the resource consent process.

Jepson says he has had little to do with waste-to-energy projects in the years since, but now he’s Kaipara mayor he says “it’s the only way to go”.

Kevin Stratful from SIRRL is set to present to Northland’s regional councils later this year.

Burn or bury?

While the debate on waste-to-energy continues in New Zealand, millions of tonnes of rubbish is burnt overseas each year.

In Europe, 27 per cent of waste is incinerated, while 23 per cent goes to landfill. In Belgium, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Austria, almost all municipal waste is incinerated or recycled with less than 2 per cent going to landfill.

In England, 48 per cent of municipal waste is now incinerated, up from 12 per cent a decade ago. According to the UK’s Climate Change Commission, the growth is because “incineration is considered to have a lower overall environmental impact compared to landfill — including in terms of emissions”.

Australia’s first waste-to-energy plant is under construction in Perth and more are being developed.

New Zealand, meanwhile, sends more rubbish to landfill than almost any country in the OECD, and it’s been increasing. In the decade after the Waste Minimisation Act was passed in 2008, the amount of municipal waste going to landfill increased by 48 per cent. New Zealand’s recycling rate is also low compared with much of Europe.

However, UK-based waste consultant Mark Hilton says waste-to-energy plants have generally been a barrier to recycling in the UK and parts of Europe. Recycling rates there have stalled at around 50 per cent over the last decade. He says this is because incineration plants require an enormous amount of rubbish each year to be viable and because they are very expensive they need to keep operating for 20 to 30 years to break even. Some also lock councils into long-term contracts where they are required to provide a minimum amount of waste each year. This all reduces the incentives to recycle.

There are exceptions, however. For example, Wales has among the highest recycling rates in the world and also has a couple of waste incinerators — although it also has a moratorium on building new plants. Germany is also a world-leader in recycling, Hilton says, and has virtually no landfills due to widespread incineration. “But to put this into context, Germany has made huge efforts to recycle with stringent policies and targets over recent decades and a well-established and very effective container-return scheme,” he says. “In Germany it also still makes some sense to burn waste as this is offsetting a long-standing dependency on their own cheap coal.”

In the UK, waste-to-energy plants have helped to significantly reduce greenhouse emissions from waste. This is because landfills emit methane when organic material breaks down in the absence of oxygen. Methane’s warming effect is about 28 times greater than carbon dioxide.

In 2021, New Zealand’s waste sector (mostly landfills) was responsible for 4 per cent of the country’s greenhouse emissions. That’s similar to the emissions from the entire electricity sector (5.7 per cent). Waste-to-energy plants avoid these methane emissions, but emit carbon dioxide, which is much less potent at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Emissions from landfill are declining markedly, however, due to systems that capture methane gas, while efforts to divert organic waste from landfill aim to cut emissions at source. As of 2021, 97 per cent of the waste taken to municipal landfills was in a facility with methane capture. On average, these systems trap about 68 per cent of a landfill’s methane (though Waste Management claims its systems capture more than 90 per cent).

Waste consultant Mark Hilton says it’s better to remove organic material from the waste-stream and bury non-recyclable plastic until we have better methods of reusing it.

This has meant that despite the volume going to landfill increasing, waste emissions have reduced by 18 per cent since 1990. The government has a target of reducing waste emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 and is investigating banning organic waste from landfills by 2030. If green waste is composted rather than buried, methane emissions are greatly reduced.

Waste-to-energy proponents claim the plants produce renewable energy. This entirely depends on the type of waste they burn. Burning organic material isn’t considered to contribute to global warming as the carbon emitted is part of the natural carbon cycle. When a plant grows it stores carbon via photosynthesis and this is released back to the atmosphere when the plant decomposes, or is burned, creating a closed cycle of emissions. By contrast, coal and oil buried underground isn’t part of this cycle and digging it up and burning it — or turning it into plastic and burning it — adds to the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.

Because more organic waste is expected to be diverted from landfill, the proportion of carbon neutral energy an incinerator produces will probably decline. And about 84 per cent of New Zealand’s electricity already comes from renewables — this is expected to be close to 100 per cent by the end of the decade — so the power from a waste-to-energy plant will be unlikely to displace coal and gas generation. SIRRL has produced an analysis showing its plant will reduce emissions compared to landfill, but this assumes that the power from the plant will displace coal and gas generation. It’s not clear whether the plant would reduce greenhouse emissions if the country’s power was 100 per cent renewable.

Mark Hilton says it’s better to remove organic material from the waste-stream and bury nonrecyclable plastic until we have better methods of reusing it. “This locks up fossil carbon, rather than releasing it, which is what incineration does.”

The proposed site of an incinerator near Glenavy is handy to the main railway line.

It’s also worth noting that waste-to-energy plants produce ash that generally ends up in landfill. The Project Kea plant will produce about 100,000 tonnes a year. About 20 per cent of this is toxic and has to be disposed of in a special landfill, although the company will use a plasma treatment to turn the ash into an inert glass-like substance. Eventually, SIRRL says, the ash will be able to be used in construction, but systems aren’t yet in place for this. In Europe, about 54 per cent of the less toxic ash is used in construction materials.

The government says waste-to-energy still has its place. Its new waste strategy lists waste-to-energy as an option for recovering value from rubbish, which it says is better than landfill. However, it says this is only preferable when the feedstock is clean biological waste, like wood or food scraps; it is critical of burning municipal rubbish. “Pyrolysis, incineration or gasification of municipal solid waste is unlikely to align with our circular economy goals, due to their negative effects on the climate, dependency on continued linear waste generation, and likelihood of causing hazardous discharge.”

The government has supported some forms of waste-to-energy when the feedstock is controlled and displaces fossil fuels. For example, Golden Bay Cement has burned about three million used tyres a year in its cement manufacturing since 2021, after a $16 million government grant towards the scheme. This has reduced its coal use by 15 per cent and its carbon emissions by about 13,000 tonnes a year.

The government is also funding feasibility studies into turning non-recyclable plastic, forestry waste and “landfill waste” into aviation fuel. Fonterra and Genesis Energy are also investigating burning wood pellets from forestry waste instead of coal in milk plants and at Huntly Power Station.

Watch this space

What happens next in Glenavy will be up to politicians. In June, Waimate District Council and ECan asked the government to step in to assess SIRRL’s resource consent. Under the Resource Management Act, if a consent is deemed to be of national significance it can be called in by the government for assessment by either a board of inquiry or the Environment Court. The criteria for national significance includes developments that have “aroused widespread public concern or interest” or “involves technology, processes or methods which are new to New Zealand and that may affect its environment”. Environment minister David Parker hasn’t yet made a decision.

The application also relies on getting permission from the Overseas Investment Office.

Other changes in the wind may also prevent the establishment of waste-to-energy plants. The government plans changes to the Waste Minimisation Act which include adding a levy to rubbish taken to waste-to-energy plants. The government already charges $50 for every tonne of waste disposed of at landfill but, for now, waste-toenergy plants are exempt from a fee; adding one could make plants uneconomical.

The new legislation may also outlaw burning municipal waste entirely. The government has proposed creating national waste standards that could determine “whether and how waste can be incinerated”.

The draft legislation is expected to be introduced to the house “in late 2023 or early 2024”. In the meantime, the people of Glenavy will have to wait and see. “There are so many unknowns,” Hannah Woods says. “That’s the trouble.”

George Driver is North & South’s junior staff writer, a role supported by NZ on Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.

This story appeared in the September 2023 issue of North & South.