Culture Etc.

Photo: Don McGlashan

The Don

Don McGlashan this year enjoyed his first number one album in his 40-something-year musical career. Ahead of a nationwide tour, he speaks to Elisabeth Easther about his years playing the French horn, taking a “normal” amount of drugs for a rock star, getting arrested during the Springbok tour and all the reasons he has to be grateful.

By Elisabeth Easther

Do people ever call you Donald?

I was going to be called David but, when I turned up, I was born with red hair and I looked so Celtic my parents didn’t think I looked like a David. Mum maintained she chose Donald for the character in Macbeth, although Dad always said I was named after Don Clarke, the famous rugby player. Either way, I became Donald Bain McGlashan, as both my brother and I were given Dad’s name as our second name.

Donald Bain McGlashan is such a Scottish name. How strongly do you connect to your Celtic roots?

I’ve been to Scotland often. The Front Lawn toured twice to the Edinburgh Festival, where we won a few awards. Scotland was also one of the first places to really embrace the Mutton Birds. Back when we couldn’t get many people to gigs in England, we’d go to Scotland and fill pubs.

One time, I went on my own to Lismore in Loch Linnhe. It’s a little one-road island an hour by ferry from Oban. I was wandering around, looking a bit lost, when a car stopped and the driver asked, “Who arrr’ yoo?” I said who I was and this person took me on a tiki tour including to the farm my ancestors left from. I was also shown the graveyard. There were only three or four surnames on the headstones and one of them was my mother’s maiden name.

Bearing in mind you played in punk bands and classical orchestras, what kind of teenager were you?

I swung wildly between all the extremes a teen can swing between. I’d play keyboards in the band and flail around writing songs, then I’d come home, have a French horn lesson then lie on the floor of my room and listen to Mahler’s Symphony No. 3. I was 15 when our band was given a residency in a venue called The Knighte Clubbe at Shore City Mall. The club owner wanted us to play Beatles covers, but we wanted to play more transgressive stuff, like David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album.

Did music feel like a possible career, or more like an intense hobby?

My French-horn teacher was from Milwaukee. One day he said to me, “I like you Don, because you’re not like a Kiwi.” I asked what he meant, and he explained how some guys he taught gave it just 70 per cent, because they’d rather be out on a boat or at the beach, but that I really wanted to make it work. Not enough, as it happened, to actually practise hard and improve — but the horn is a very unforgiving instrument.

You’ve lived such a varied musical life. How did you avoid being constrained by one genre or style?

In the early 80s, just after Blam Blam Blam, I went to Paris as part of From Scratch. We were a kind of living exhibit in the Museum of Modern Art. We’d rig up our gear in the morning and perform two shows a day for a month. It was wonderful to step away from rock ’n’ roll and be surrounded by visual arts. It was then I realised art doesn’t have boundaries. Once you choose your discipline — or it chooses you — when you’re making music or dance, or presenting stories to people, creativity defies limitations.

Blam Blam Blam’s “There Is No Depression in New Zealand” was adopted as an anti-tour song, was it intended to be a protest song?

Richard von Sturmer wrote the lyrics and I wrote the music. It started out as a shout against the grey, Muldoonist complacency we’d known as teenagers, but a few months later people started to adopt it as an anti-tour anthem, and since then it’s become strongly associated with that period.

What was your involvement with the Springbok tour protests?

I was arrested during the third test, in Royal Tce. A bunch of us were handcuffed and taken under the stands. We’d been trying all day to get into the grounds, but it turned out all we had to do was get arrested. However, we couldn’t go anywhere as we were in a locked room. When we were taken to Auckland Central for processing, I was put in cell with one of my favourite Auckland University English lecturers, the late Sebastian Black. We sat in the holding cell and talked about Beckett until they let us out. So, it wasn’t your typical imprisonment.

“Mum was friends with a doctor and she once said to him, ‘It’d be great if Don could be a doctor like you, and use his talents to help people.’ This guy replied that my music might make people happy. I don’t remember how old I was at the time, but mum reported back with approval that somebody she approved of approved of my music.”

The Front Lawn is very acting- adjacent. Did you always have thespian inclinations?

Harry Sinclair and I returned to New Zealand around the same time. He’d been studying physical theatre in Paris with Monika Pagneux, a student of [the French clown master Philippe] Gaulier, and I’d been playing drums with Laura Dean Dancers and Musicians in New York. Harry wanted to get back into writing and making theatre, but he didn’t want to be part of a theatre company, doing other people’s plays. He wanted to make his stories, but less structured than having an audience sit comfortably and be fed what they expect. We both wanted to do something more energetic, more rock ’n’ roll. The more we talked, the more we realised that a musical theatre two-hander could be the answer. Just two people telling a story.

The Front Lawn is a beloved staple of Kiwi culture. Why did it have to end?

The Front Lawn lasted for six years, with Jennifer [Ward-Lealand] joining us for the last two. Harry and I learnt a lot about writing and performing through that time, but all things run their course. Harry was keen to write and direct his own movies, and I was keen to do something more purely musical.

And so the Muttonbirds were born. How did you create that very specific sound?

People struggled to describe the Mutton Birds. Some people called us “power pop”, others called us “folk rock”. But we were louder than folk rock and dirtier than power pop. Someone else said we were like other bands out of New Zealand, like Split Enz, but with a sense of some Australian bands like the Go- Betweens or the Triffids, but mainly we were the intersection of what everyone in the band was listening to. One thing I loved about the Mutton Birds, it was like another school, where we learned how to do what we were doing in front of people.

Top left: McGlashan on tour in New Zealand with Blam Blam Blam, 1981. Photo: Jenny Pullar.

Top right: Another local tour with From Scratch.

Bottom left: Edinburgh, 1989, while on tour with From Scratch.

Bottom right: With Scott Colhoun (right, on trumpet), guesting with Pop

Have you had to work many non-musical jobs?

I do worry that I’m not a good template for other New Zealand musicians, because the other work I’ve done to feed the family has always been music-related, like writing film scores, or music for dance or theatre. I think that’s pretty rare, and it’s largely down to luck.

Film scores allow you to stretch out, become immersed in someone else’s narrative, and be part of a big team, while TV is fast turnover, so you have to pull finger to hit deadlines and do consistently good work, but it’s also super fun.

How rock ’n’ roll has your life been? In terms of parties and drugs and all that jazz?

I probably took what you would call a normal amount of drugs when I was younger. I certainly took enough to realise I wouldn’t be very productive if I kept doing them, so I stopped. A lot of rock ’n’ roll people take drugs because they’re bored, or unsure of themselves or depressed. I have certainly been the latter two, but I don’t really do boredom.

That’s handy. How do you avoid the old ennui?

I get energy from just doing stuff. If someone asks me to join their project, I never ask myself “Will I look cool if I do this?” Usually I just think it’ll be fun, so I say yes. Life’s quite short, and you can limit your possibilities by being cool. Besides, we’ll all be very cool when we’re dead — cold in fact — so while we’re alive, we might as well swing wildly at life, even if sometimes we miss.

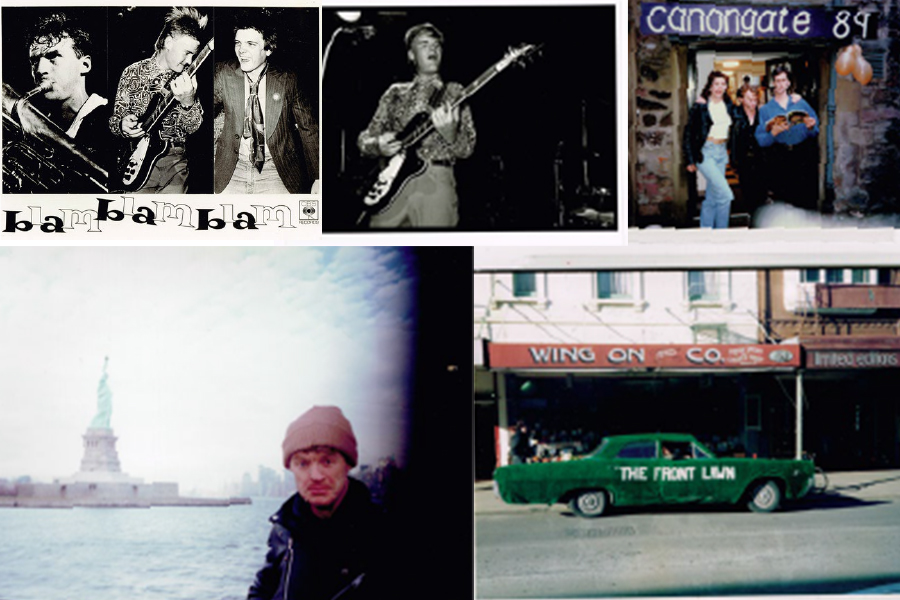

Top left: A CBS New Zealand promo for Blam BlamBlam. From left, McGlashan, Mark Bell, Tim Mahon.

Top middle: Mark Bell playing guitar in the Blams.

Top right: With Jennifer Ward-Lealand and Harry Sinclair at the Edinburgh Festival, 1989.

Bottom left: McGlashan in New York, 1990.

Bottom right: The Front Lawn’s “Lawnmobile”, parked on George St in Dunedin, some time in the late 1980s or early 90s.

How have you dealt with the downs?

I’ve never dealt with them very especially well, but I’ve tended to work through them. That’s the Presbyterian in me. Being in the UK was really hard at times, like when the record-company income got patchy between tours. In New Zealand, I could just phone people and ask, “Do you have a project and if yes, can I be part of it, because I’m skint?” All New Zealand performers and musicians make those calls from time to time, and everybody helps each other. But nobody knew us in England.

You can certainly hear those hard times in the two albums we made in London, that longing for home.

“I was arrested during the third test in Royal Terrace. A bunch of us were handcuffed and taken under the stands. We’d been trying all day to get into the grounds, but it turned out all we had to do was get arrested.”

Do pain and struggle help inspire you to write songs?

I wrote a lot of songs there that were letters home. I was unpacking my memories of growing up in Aotearoa. Then, when we came back from England, I wrote, paradoxically, some songs about being in England.

In my first solo album there is a song called “This Is London”, about putting our daughter to sleep in our flat and listening to the night train as it went across the top of the valley. But I needed to be back home in New Zealand to sift through those impressions and knock them into shape before I could make songs about them.

I love your song “Andy” [from the 1989 album, Songs from the Front Lawn]. Can you tell me about it?

We lost my older brother when I was 15. He was 20 and he died in a boating accident with two of his friends. Some years later, I was working on songs for the Front Lawn and I started one where two brothers were talking. It was going to be about the changes in New Zealand, with Rogernomics, when everything was de-regulated at a furious rate and the countryside was being emptied out.

There was a strong sense of “fend for yourself ” as we were all pushed into this brave new world of glass and concrete. I wanted to write about a country brother and a city brother, with the birthday event to hang it off. I worked on it for a while then played it to Harry and he said, “This is about your brother isn’t it? Why not tell that story? Take away the scaffolding, and make it more about one thing”. He pushed me to go right into the centre of the song.

It became part of the Front Lawn set, but not attached to any particular story, like a step sideways, an interlude where I’d play the mandolin and Harry played the concertina. I tried to create some distance from reality though. My brother wasn’t called Andy because I wanted to separate the song from my family’s story and the other families involved. When you write about pain that’s not just your own, you have to tread carefully.

Looking ahead, what does your future hold?

I’m 63, and I have a feeling of blessedness and luck that I’ve got to this ripe old age and I just had my first number-one album. I’m also looking forward to touring this record but, for the future, I want to keep making songs that give people some joy, or make them feel more alive or less alone. I want to keep doing that.

Elisabeth Easther is a North & South contributing writer.

This story appeared in the October 2022 issue of North & South.