Culture Etc.

A portrait of Culbert from 1957. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library

Portrait of the artist as a dead man

In 2019, New Zealand conceptual artist Bill Culbert died at his home in southern France, where he’d maintained a studio for six decades. It took three years and a 40-foot container to get the studio’s contents to Aotearoa. North & South asked the gallery looking after Culbert’s estate what makes it worth preserving.

By Theo Macdonald

My father collected cricket almanacks. He died six years ago. My mother still hasn’t figured out what to do with the 15 shelves of canary-yellow reference books. Recently, a friend showed me cellphone photos of his mother’s collection of first-edition Agatha Christie novels, bought in multiples in the 60s and 70s. Next month, his parents are selling the books. They’re moving into a retirement village and haven’t got the room to store them.

It’s a common problem. What should you do with your parents’ possessions as they age and die? We spend our lives amassing objects, many as precious as a beautifully bound copy of Murder on the Orient Express, but there’s a limit to what the next generation can or wants to keep, and hard decisions must be made.

But what if your parents’ possessions are part of something bigger and more significant? What if, as is the case for the children of Bill Culbert, the objects your parents collected are part of New Zealand’s artistic heritage? What are your obligations? And who will help manage them?

The waiting room

The air-controlled storage unit in Papakura, empty of other visitors on this wet winter morning, could seem sombre, even numbing, were it not for the mid-2000s pop bangers bouncing down the concrete hallways. Tyler Jerrom, a gallery assistant at Auckland’s Fox Jensen McCrory Gallery (FJM), tells me the playlist is the same every time he comes out here. A Miley Cyrus power ballad (“I can almost see it / That dream I’m dreaming”) is not the burial hymn you might expect at the temporary, symbolic resting place of one of New Zealand’s most celebrated artists. But Bill Culbert’s creative practice, spanning sculpture, photography, painting and installation, welcomed the unexpected.

Bill Culbert was born in Port Chalmers in 1935. His family traces their settlement in Otago to pirates. He studied painting in Christchurch, living in a dilapidated Victorian mansion with Ilam peers such as Hamish Keith and Pat and Gil Hanly. In 1957, Culbert moved to London’s Royal College of Art on a scholarship. Four years later, Culbert and his wife, artist Pip Culbert, bought a property at Croagnes, in the Vaucluse region of Provence, for only £100. They spent their lives between Croagnes, London and New Zealand, although all accounts suggest Croagnes was where Culbert preferred to live and work. It is also where he died, in early 2019, leaving a son and daughter, Ray and Collette.

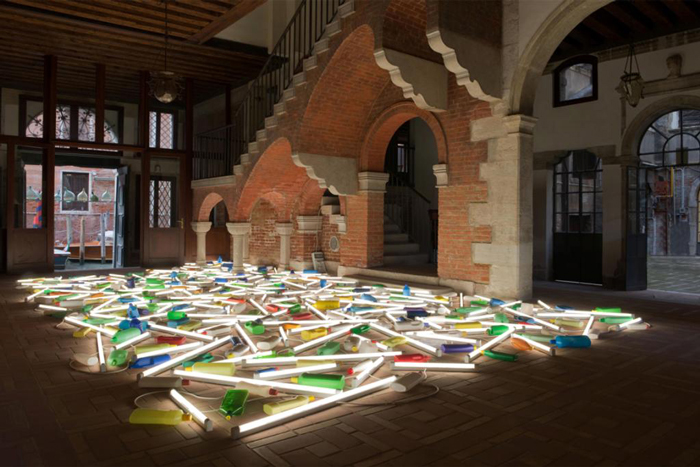

The first object Jerrom pulls from the storage unit (one of four in Auckland full of Culbert material) is a self-portrait he painted in 1953. The delicate figure’s alert stare is a motif from a less abstract era. Culbert’s representatives say the New Zealand public does not understand the recognition the artist received overseas. This painting portrays a young man, unaware he will one day install permanent light artworks throughout Europe, the UK and Aotearoa, become a member of the New Zealand Order of Merit and represent his nation at the 55th Venice Biennale.

Before the studio was packed down, Culbert’s family removed objects of personal significance. The Centre Pompidou, France’s illustrious museum of modern art, selected certain works, settling Culbert’s estate in France — a thick document records every Culbert work collected by the Pompidou. And then, as Jerrom says, “Everything else came to us. Everything else.”

Left: Bill Culbert, Self Portrait, 1953.

Right: Boxes of Culbert’s artwork at a Papakura storage unit.

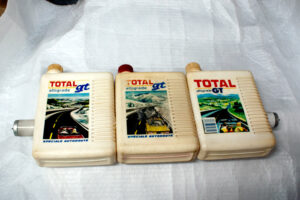

Right: Original Total-brand engine oil containers that inspired a series of light sculptures.

Right: One panel of triptych painting The People of Armagh Street, 1956.

Founded by Andrew Jensen in 1988, FJM is one of many commercial galleries, worldwide that represented Culbert during his long life. Not every gallery has the capacity to continue their stewardship of an artist’s practice after their death. The decision to take responsibility for managing the Culbert estate was not one FJM took lightly. Emma Fox, FJM codirector, sighs, “My life is the logistics of packaging and shipping artworks”. She doesn’t find the challenges of bringing Culbert’s studio home as interesting as I do, although the magnitude of the task, let alone the responsibility, was always apparent. One trustee of Culbert’s estate, who Fox declines to name, advised, “You’ll never get that out of France”.

Jerrom pulls out another painting, carefully slicing open the red, white and blue Bishop’s Move packaging. It is a triptych of the Christchurch art gang who occupied the Armagh St mansion. Over seven decades, between Christchurch and the South of France, one of the three panels vanished.

She doesn’t find the challenges of bringing Culbert’s studio home as interesting as I do, although the magnitude of the task, let alone the responsibility, was always apparent.

Before even getting to the cargo ship, every object had to be itemised, sealed in bubble wrap and transported along rural motorways. This included eight boxes of loose fluorescent tubes — one of the sculptural materials Culbert is most associated with — in eight different sizes. The shipping paperwork alone took six months. When the container finally arrived in New Zealand, further delayed by the pandemic, Customs held a selection of wooden sculptures as a biosecurity hazard (they were released weeks later).

The container’s contents include artworks from the artist’s private collection (some of them major installations), prototypes for sculptures, photo negatives and preparatory drawings, as well as copies of every publication Culbert produced. Jerrom tells me they recently sent 250 kilograms of books to a storage unit in Christchurch. In the next few years, FJM hopes to house some of the significant works in public institutions, accompanied by development materials (prototypes, drawings, notebooks) that will help future artists understand Culbert’s studio process. An original Total-brand engine oil container, for example, which prompted a series of plastic bottle light sculptures, or an assortment of Roman bricks that became binoculars in a whimsical photo series.

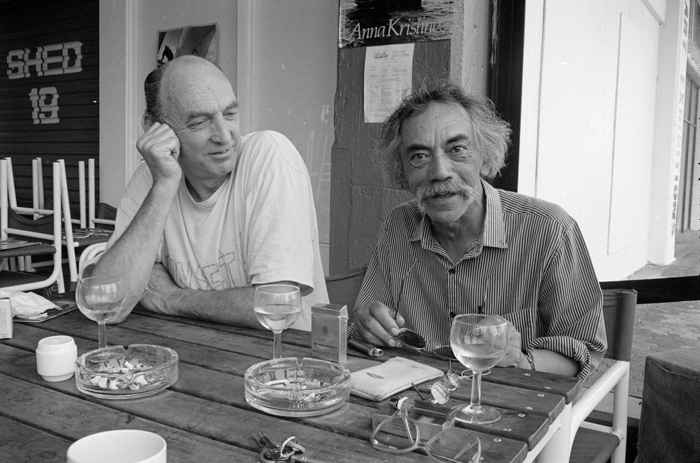

Bill Culbert and Ralph Hotere at the Princes Wharf Café, photographed by Gil Hanly in 1991. Photo: Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

For Jerrom, who trained in art history and museum heritage, taking on a vital role in the accession of Culbert’s studio has been a trial by fire. His duties with the estate encompass electrician, tax accountant, motorist, writer and archivist. “The Culbert estate is so wide and varied that the way of storing one facet of it, like the photographs, is completely turned upside down if you try to apply it to something else, like the exhibition posters.” Stringent itemisation means Jerrom knows roughly what each box contains, and the layout of the storage locker is etched into his brain.

When I first approached FJM, the gallery expressed concern about publicising the contents of the storage unit. They worried the public might perceive the reference objects and unfinished tests as a pile of old junk. Visiting the site, it is evident that the storage unit is less a junk shop; more a magician’s toolbox.

The artist’s studio can be said to give insight into the artist’s fundamental nature; what really made the artist tick. The same may be true of the baker’s kitchen or the public-relations manager’s Rolodex (before the 90s). Portrait photographer Richard Avedon preferred photographing his subjects — from J. Robert Oppenheimer to Tina Turner — in the studio, saying, “They become in a sense… symbolic of themselves.”

Despite a lifetime of exhibiting throughout Europe, Culbert maintained his sense of Kiwi ingenuity. The decision to preserve his studio is a mark of this distinction. Jerrom speaks of Culbert, who he never met, with the familiarity of a young man remembering a legendary grandfather. “He wanted to be in the middle of nowhere, near the town dump, and toil away with his own work.” When

Jerrom started working with the collection, he was told a story about Culbert being awarded a mayor’s honour medal. Culbert turned up to receive the medal but decided to go to the local flea market and missed the ceremony. “That sums him up to a T.” Jerrom asks if there’s anything I’m particularly interested to see. I look at cardboard boxes with enigmatic titles written across them: “Mr Nesquik” and “Where are the other two?” I’m curious about the prototypes that never became exhibited artworks. Jerrom weaves through the shelves and pulls out a small box. Inside, carefully swaddled, is a cabbage-sized lump of fossil, ridged along the top, with a rustic lightbulb embedded within. Find something, deconstruct it, reconstruct it with a new function. In doing so, Culbert revealed the world anew.

In Aotearoa, Culbert is perhaps best known for his collaborations with his friend Ralph Hotere. Wellingtonians will be familiar with Fault, the joint installation integrated into the facade of City Gallery Wellington. The collaborations contain motifs of them as individual artists, including Culbert’s fluorescent tubes and Hotere’s stark black panels, which together create a unique creative voice. But it is more than artistic achievement that keeps Culbert’s Hotere collaborations in mind when discussing the Culbert estate.

Since the founding of the Hotere Foundation Trust in 2003, 10 years before the artist’s death, family members and senior arts figures have voiced concerns about how the trust handles Hotere’s legacy. Notably, conflicts with the trust meant that Vincent O’Sullivan’s 2020 biography of the artist, Ralph Hotere: The dark is light enough, couldn’t include a single Hotere artwork. Hotere’s daughter Andrea told Stuff, “I believe the foundation has had a repressive effect on scholarship related to Dad.” In the same article, art consultant Hamish Coney comments, “What the trust is effectively doing is, over time, erasing Ralph Hotere from the cultural discourse, because everybody knows, in the art world, that it’s a no-go zone.”

As the Hotere case demonstrates, managing an artist’s legacy is more than moving boxes and counting money. And there are plenty of practical matters to address in Culbert’s case; take the electrical components to his light works for example. Jerrom laughs remembering the gallery’s on-call electrician tasked with rewiring older Culbert light works — a three-hour appointment per sculpture — declaring that he’d happily never see one of Culbert’s plastic bottles ever again. “The hardest part about getting a lot of these works exhibition-ready is the electrical side of it; making sure it’s not going to burn someone’s house down.” He gives an example of the sculptural work Total Black, a sequence of identical black plastic bottles skewered on a fluorescent tube. “Total Black didn’t come to us with any sort of wiring or caps for the end of the fluorescent tubes. So what we’ve had to do, because the caps for that particular type of fluorescent bulb are out of production, is use particular fittings for the newer bulbs. They’ll sit on the ends of the older ones… There is also an issue of longevity in some of the early works because they’re not as energy efficient, and they get quite hot. In some cases, we have to warn a client that you can’t have this work on 24-7. It will melt, essentially.” In the mid-90s, Culbert switched to a more modern bulb, which can stay on continuously.

Front Door Out Back in Instituto Santa Maria della Pieta, Venice Biennale, 2013. Photo: Jennifer French, courtesy of Creative New Zealand

For the moment, everything is up in the air. I ask Jerrom how long it might take before things settle down. “We mostly have a grip on what we have, but we’re still getting the sense of what we need to do for them to be ready [for sale].” Such arrangements will be made in the next few years, and the collection may become more self-moderating. Jerrom sees himself stepping back from the Culbert estate around then.

The Culbert Estate, FJM and Tyler Jessom have committed a lot of work and money to make sure the public can enjoy Culbert’s creative endeavours and future artists can continue studying his methods. He was an exceptional artist. However, in terms of these collected paintings, photo negatives, notebooks, prototypes and sculptures being evidence of time and experience, and a process of self-realisation, Culbert’s legacy has much in common with anyone else’s. As his recycling of artefacts repeatedly demonstrated, interpreting the past is one fundamental step toward understanding the present.

This story appeared in the October 2023 issue of North & South.