Culture Etc.

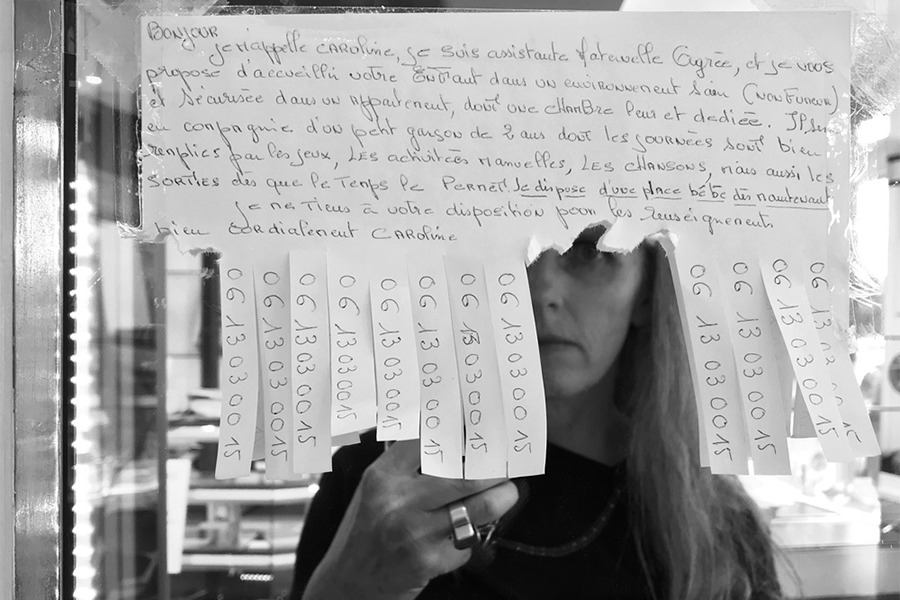

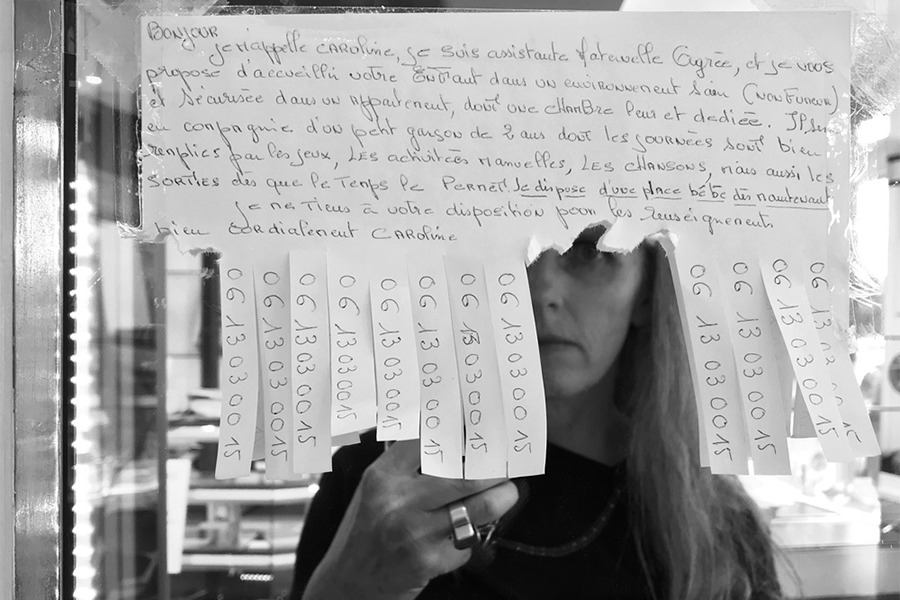

Self-portrait by Catherine Griffiths

Saying the quiet part in 72pt font

Renaissance woman Catherine Griffiths tells North & South why she’s fed up with design industry inequity, and what she’s doing to fight it.

By Theo Macdonald

In Catherine Griffiths’ Karekare home, in Auckland’s Waitākere Ranges, every object, from the custom-built bookshelf to the Alessi coffee pot, is cultivated. She lives with her husband, photographer Bruce Connew, and the pair’s harmonious aesthetic fluency even extends to preparing cheese on bread. The crumbly cuts of Hohepa cheese are arranged with such delicate asymmetry that the plate of food appears to be, at first glance, a small sculpture. A designer, typographer, artist, educator, publisher and activist, Griffiths rejects labels, classifications and categories. Our first phone call reveals this firm self-determination. She evades any line of questioning that might curb the boundaries of her creative capacity. But, restricting as they may be, labels are the journalist’s obligation. So, let’s try a few on and see what sticks.

Catherine Griffiths is experienced. Griffiths entered the design industry in the mid-80s after studying at the Wellington Polytechnic School of Design, at the suggestion of her art teacher Mrs Zilch, who “smoked like a chimney”. When North & South visited Griffiths’ studio, she pulled from storage her copy of the 1986 vinyl record He Waiata Mo Te Iwi by Māori band Aotearoa. Griffiths designed the record sleeve when she was only 21 years old, and recalls walking over to the typesetter’s office to ensure the band’s name was rendered in bold, spaced out lettering, to convey its provocative brilliance.

Catherine Griffiths is independent. Less than 10 years after graduation, she opened a solo practice, today called Studio Catherine Griffiths, with clients including Creative New Zealand,Victoria University of Wellington and Wools of New Zealand. Despite the scope of these projects, she decided against hiring assistants, managing each client’s needs and deliverables independently. It gives her total autonomy. Griffiths also takes pride in her readiness to let clients go if their needs are out of step with her ethical and political values.

Catherine Griffiths is a collector. When she was a small child, her great-great-aunt gave her a cloth bag of pennies; she still has the pennies, wrapped in their original parcel with a handwritten note. Griffiths is also a lifelong diarist, with the entire diary collection on hand anytime she needs to remember. When she and Connew first got text-capable cellphones in the early 2000s (Nokia flip-phones with limited memory), he went to Fiji to take photographs and Griffiths would retype their text exchanges word for word into a digital QuarkXPress document formatted to the size of the phone screen. Eventually, this digital record became a concertina book project in a single edition, which has been buried in a time capsule. Griffiths was such an early adopter of texting that Vodafone sent her a Sony Discman.

(Left to right) One of Griffiths’ 2018 protest posters which gave rise to Designers Speak (Up). Alessandra Banal and Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho’s contributions to Present Tense : Wāhine Toi Aotearoa.

Most of all, Catherine Griffiths is busy. North & South is visiting her to talk about Present Tense : Wāhine Toi Aotearoa — a paper record, a poster and exhibition project-turned-book which Griffiths instigated, edited, designed and printed over the past five years. She also has an abstract wall painting, 7/7, 14 views, installed at Auckland’s Te Tuhi art gallery until 22 October and, at the same time, is part of Sophia Smolenski’s exhibition Offering It Up at Wellington’s Adam Art Gallery Te Pataka Toi. On top of those projects, there’s her ongoing commercial work and involvement with the advocacy platform Designers Speak (Up), the community-building ethos of which developed from the 2009 typography symposium TypeSHED11 and a series of workshops over the past decade.

For Griffiths, making space means understanding how you want to be in that space, and requires careful attention to natural light, temperature and orientation. Her first studio was in Wellington’s art-deco landmark, the Hibernian Building. Her first home studio was an adapted streetfront garage with fire station doors, in a house designed by Stevens Lawson Architects (for whom Griffiths designed a still-in-use visual identity). Later, she worked from the wardrobe of an apartment in the city. Griffiths and Connew designed and built their house in Karekare (with support from Athfield Architects) when they moved from Wellington to Auckland, after their five children (Griffiths’ step-children) left home. The house, with wide windows looking into the bush, mirrors the dimensions of the boat in France on which they spend three months of most years. On the same slope of bush, each has a studio they constructed by “hammer and hand”.

Griffiths (far left) with contributors to Present Tense : Wāhine Toi Aotearoa at Te Tuhi art gallery for the Auckland book launch. Right: Graphic designer Katie Kerr at the launch.

Present Tense originates from a 2018 protest. Frustrated that, of 43 prestigious Black Pin awards given by the Designers Institute of New Zealand over two decades, only three had gone to women (as of publication, the number has swelled to five), Griffiths released a poster series across Instagram, Facebook and Twitter to bring awareness to this inequity. “Enough was enough. This was the moment to strike at a system that holds enormous sway and power.”

Her protest brought to the boil long-simmering conversations about the institution’s negligence toward non-male designers, provoking flame wars, a secret Facebook group and the initiation of Designers Speak (Up). Soon after, Designers Speak (Up) organised a protest, with the support of Auckland Feminist Action, outside the 2018 Best Design Awards. The following day, coinciding with the 125th anniversary of the Aotearoa suffrage movement, Designers Speak (Up) unveiled the Directory of Women* Designers.

“Enough was enough. This was the moment to strike at a system that holds enormous sway and power.”

Throughout her career, Griffiths has often returned to the poster format. The catalogue for her 2019 survey exhibition SOLO IN [ ] SPACE swells with striking, vivid, expressive typographic work. As she puts it, the poster is the perfect tool for inciting political communities. After the first wave of action in 2018, Designers Speak (Up) put out an open call for poster submissions, eventually receiving 115, which formed the basis for an exhibition hikoi through Hamilton, Dunedin, Kaikohe, Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington.

Each submission had to be A1, accompanied by a brief descriptive text, and set in just two colours — red (specifically, hexadecimal red #ff 3333) and white. The poster could address any topic, and every entry was automatically accepted — the antithesis of an exclusionary design award. Griffiths was impressed by the courage of the submissions from all over the motu, the concerns of which included xenophobia, environmentalism, the gender pay gap, gun violence and indigenous struggle. The book (“a paper record”) collects every poster, alongside photographs of the exhibitions and commissioned essays.

The Auckland book launch, held in a cosy Te Tuhi conference room felt more like an activist hui than a commercial promotion. Speeches by Griffiths and contributors Desna Whaanga-Schollum, Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho and Alice Murray were marked by references to unnamed design industry gatekeepers (one nicknamed “Voldemort”) with whom the crowd were familiar and frustrated. Looking around the room, North & South spotted design and publishing industry maestros nodding in agreement.

Photos: Andrew Kennedy

A project like Present Tense, that opens up a feminist critique of the national design industry, has clearly been a long time coming. Midway through our conversation, Griffiths tells an off -the-record story about being caught in the bureaucracy of another prestigious (male-dominated) design institution. After this experience, she knew she’d rather remain outside. There’s great power in being an outsider. “After the posters ignited the community and conversation… the institute, as predicted, exercised brief tokenism, making soft change (there are more women on the juries for example, but no fewer men), [while remaining] seemingly on the same path.”

Griffiths is conscious of how her age and experience puts her in a privileged position to advocate for women and non-binary designers. “Even as a young designer, going back to my 20s, early 30s, I stood up for what I felt was right, for integrity, authenticity, honesty.” She believes it is the duty of designers young and old to know their industry, and its problems, through and through.

“I’ve taken enormous risks. I know what it is to be uncomfortable. And I continue to, albeit with more knowledge and context under my belt.” Reflecting on our conversation on the road back to the city, out of the Waitākere bush, uncompromising feels like the label that sticks best. Some of the contributors to Present Tense have suggested entering the book into the Best Design Awards, credited to every contributor. Catherine Griffiths prefers to boycott the awards and put that energy into building a better, more equitable community somewhere else.

Present Tense : Wāhine Toi Aotearoa — a paper record is published by Vapour Momenta Books. Limited copies are available from Te Tuhi, Blue Oyster and Evening Books, and Designers Speak (Up), designersspeakup.nz/shop/.

This story appeared in the October 2023 issue of North & South.